Shonisaurus

| Shonisaurus Temporal range: Late Triassic, 215 Ma | |

|---|---|

| |

| Restored skull | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | †Ichthyosauria |

| Infraorder: | †Shastasauria |

| Family: | †Shastasauridae |

| Genus: | †Shonisaurus Camp, 1976 |

| Species: | †S. popularis |

| Binomial name | |

| Shonisaurus popularis Camp, 1976 | |

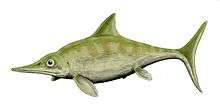

Shonisaurus is a genus of ichthyosaur. At least 37 incomplete fossil specimens of the marine reptile have been found in the Luning Formation of Nevada, USA. This formation dates to the late Carnian age of the late Triassic period, about 215 million years ago.[1]

Description

Shonisaurus lived during the Norian stage of the late Triassic period. S. popularis measured around 15 metres (49 ft) long. A second species from British Columbia was named Shonisaurus sikanniensis in 2004. S. sikkanniensis was one of the largest marine reptiles of all time, measuring 21 metres (69 ft). However, phylogenetic studies later showed S. sikanniensis to be a species of Shastasaurus rather than Shonisaurus.[2] A new study, of the year 2013, reassert the original classification, finding it more closely related to Shonisaurus than to Shastasaurus.[3] Specimens belonging to S. sikanniensis have been found in the Pardonet Formation British Columbia, dating to the middle Norian age (about 210 million years ago).[1]

Shonisaurus had a long snout, and its flippers were much longer and narrower than in other ichthyosaurs. While Shonisaurus was initially reported to have had socketed teeth (rather than teeth set in a groove as in more advanced forms), these were present only at the jaw tips, and only in the very smallest, juvenile specimens. All of these features suggest that Shonisaurus may be a relatively specialised offshoot of the main ichthyosaur evolutionary line.[4] It was historically depicted with a rather rotund body, but studies of its body shape since the early 1990s have shown that the body was much more slender than traditionally thought.[5] S. popularis had a relatively deep body compared with related marine reptiles.[1]

Shonisaurus was also traditionally depicted with a dorsal fin, a feature found in more advanced ichthyosaurs. However, other shastasaurids likely lacked dorsal fins, and there is no evidence to support the presence of such a fin in Shonisaurus. The upper fluke of the tail was probably also much less developed than flukes found in later species.[6]

History

Fossils of Shonisaurus were first found in a large deposit in Nevada in 1920. Thirty years later, they were excavated, uncovering the remains of 37 very large ichthyosaurs. These were named Shonisaurus, which means "lizard from the Shoshone Mountains", after the formation where the fossils were found.

S. popularis, was adopted as the state fossil of Nevada in 1984. Excavations, begun in 1954 under the direction of Charles Camp and Samuel Welles of the University of California, Berkeley, were continued by Camp throughout the 1960s. It was named by Charles Camp in 1976.[7]

The Nevada fossil sites can currently be viewed at the Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park.

Bonebed interpretation

The Nevada bonebed represents a large assemblage of Shonisaurus which died at varying times and became preserved on the sea floor in a curiously regular arrangement of bones. The lack of fossil invertebrates encrusting the remains indicates that the carcasses sank in relatively deep water poor in oxygen.

Alleged predation by "Triassic kraken"

In a 2011 lecture to the Geological Society of America, Mark McMenamin and Dianna Schulte McMenamin, geologists from Mount Holyoke College, put forward the controversial hypothesis that the large assemblage of remains were placed in deep water by an unidentified, gigantic, squid-like predator they referred to as a "kraken". The McMenamins went on to suggest that the arrangement of the vertebrae, which appear to resemble cephalopod suction organs of cephalopod tentacles in their round, concave shape, were purposefully arranged by a Triassic kraken (which they suggested would have had to be extremely intelligent) in order to create a work of art, specifically a self-portrait of its own tentacles.[8] This hypothesis was widely reported by the news media when the Geological Society of America issued a press release in October 2011. Critics were concerned that there was only trace fossil evidence favoring the existence of the Triassic kraken. Science author Brian Switek, writing for the Wired magazine's Laelaps web log, made the following comment:

"[T]he fact remains that journalists should have actually done their jobs rather than act as facilitators of hype. You don’t have to be a paleontologist to realize that there’s something fishy about claims that there was a giant, ichthyosaur-crunching squid when there is no body to be seen."[9]Other writers responded more favorably to the McMenamins' proposal. Writing for About.com, Andrew Alden wrote that the concept of high intelligence in the Triassic kraken hypothesis "is its most valuable contribution: why should we rule out intelligence in the distant past? And what would the signs of it be?"[10]

See also

- Largest prehistoric organisms

- Shastasaurus, a relative of Shonisaurus

- Temnodontosaurus, another large ichthyosaur

- List of ichthyosaurs

- Timeline of ichthyosaur research

Notes

- 1 2 3 Nicholls, Elizabeth L.; Manabe, Makoto (2004). "Giant Ichthyosaurs of the Triassic—A New Species of Shonisaurus from the Pardonet Formation (Norian: Late Triassic) of British Columbia". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 24 (4): 838–849. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2004)024[0838:GIOTTN]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0272-4634.

- ↑ Sander, P. Martin; Chen, Xiaohong; Cheng, Long; Wang, Xiaofeng (2011). Claessens, Leon, ed. "Short-Snouted Toothless Ichthyosaur from China Suggests Late Triassic Diversification of Suction Feeding Ichthyosaurs". PLoS ONE. 6 (5): e19480. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0019480. PMC 3100301

. PMID 21625429.

. PMID 21625429. - ↑ Ji, C.; Jiang, D. Y.; Motani, R.; Hao, W. C.; Sun, Z. Y.; Cai, T. (2013). "A new juvenile specimen of Guanlingsaurus (Ichthyosauria, Shastasauridae) from the Upper Triassic of southwestern China". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 33 (2): 340. doi:10.1080/02724634.2013.723082.

- ↑ Palmer, D., ed. (1999). The Marshall Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals. London: Marshall Editions. pp. 78–79. ISBN 1-84028-152-9.

- ↑ Kosch, Bradley F. (1990). "A revision of the skeletal reconstruction of Shonisaurus popularis (Reptilia: Ichthyosauria)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 10 (4): 512–514. doi:10.1080/02724634.1990.10011833.

- ↑ Wallace, D.R. (2008). Neptune's Ark: From Ichthyosaurs to Orcas. University of California Press, 282pp.

- ↑ Hilton, Richard P., Dinosaurs and Other Mesozoic Animals of California, University of California Press, Berkeley 2003 ISBN 0-520-23315-8, at pages 90-91.

- ↑ McMenamin, M.A.S.; Schulte McMenamin, D.L. (2011). "Triassic kraken: the Berlin Ichthyosaur death assemblage interpreted as a giant cephalopod midden". Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs. 43 (5): 310.

- ↑ Switek, B. (2011). "The Giant, Prehistoric Squid That Ate Common Sense." Wired: Laelaps. Web log entry, 10-OCT-2011. Accessed 11-OCT-2011 http://www.wired.com/wiredscience/2011/10/the-giant-prehistoric-squid-that-ate-common-sense/

- ↑ Alden, A. (2011). "The Great Kraken Fracas." About.com: Andrew Alden. Web log entry, 14-OCT-2011. Accessed 18-OCT-2011 http://geology.about.com/b/2011/10/14/the-great-kraken-fracas.htm/

References

- Dixon, Dougal. "The Complete Book of Dinosaurs." Hermes House, 2006.

- Camp, C. L. (1980). "Large ichthyosaurs from the Upper Triassic of Nevada". Palaeontographica, Abteilung A. 170: 139–200.

- Camp, C.L. 1981. Child of the rocks, the story of Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park. Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology special publication 5.

- Cowen, R. 1995. History of life. Cambridge, Mass.: Blackwell Scientific.

- Hogler, J. A. (1992). "Taphonomy and Paleoecology of Shonisaurus popularis (Reptilia: Ichthyosauria)". PALAIOS. 7 (1): 108–117. doi:10.2307/3514800. JSTOR 3514800.

- McGowan, Chris; Motani, Ryosuke (1999). "A reinterpretation of the Upper Triassic ichthyosaurShonisaurus". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 19: 42–49. doi:10.1080/02724634.1999.10011121.

- Motani, Ryosuke; Minoura, Nachio; Ando, Tatsuro (1998). Nature. 393 (6682): 255–257. doi:10.1038/30473. Missing or empty

|title=(help)