Sex trafficking

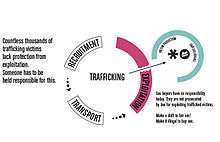

Sex trafficking is composed of two aspects: sexual slavery and human trafficking.[1] Theses two aspects represent the supply and demand side of the sex trafficking industry, respectively. This exploitation is based on the interaction between the trafficker selling a victim (the individual being trafficked and sexually exploited) to customers to perform sexual services.[2] These sex trafficking crimes are defined by three steps: acquisition, movement, and exploitation.[1] The various types of sex trafficking are child sex tourism (CST), domestic minor sex trafficking (DMST) or commercial sexual exploitation of children, and prostitution.[2]

According to a UN report from 2012, there are 2.4 million people throughout the world who are victims of human trafficking at any given moment.[3] In this annual US$32 billion industry, 80 percent of victims are being exploited as sexual slaves.[3]

For the International Labour Organization, there are 20.9 million people subjected to forced labour, and 22 percent (4.5 million) are victims of forced sexual exploitation.[4] However, due to the covertness of the sex trafficking industry, obtaining accurate, reliable statistics proves difficult for researchers.[5]

Most victims find themselves in coercive or abusive situations from which escape is both difficult and dangerous. Locations where this practice occurs span the globe and reflect an intricate web between nations, making it very difficult to construct viable solutions to this human rights problem.

Defining the issue

Global

In 2000, countries adopted a definition set forth by the United Nations.[6] The United Nations Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime, Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children, is also referred to as the Palermo Protocol. The Palermo Protocol created this definition.[6] 147 of the 192 member states of the UN ratified the Palermo Protocol when it was published in 2000.[6] Article 3 of the Palermo Protocol states the definition as:[7]

(a) "Trafficking in persons" shall mean the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation.Exploitation shall include, at a minimum, the exploitation of the prostitution of others or other forms of sexual exploitation, forced labour or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude or the removal of organs;

(b) The consent of a victim of trafficking in persons to the intended exploitation set forth in subparagraph (a) of this article shall be irrelevant where any of the means set forth in subparagraph (a) have been used;

(c) The recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of a child for the purpose of exploitation shall be considered "trafficking in persons" even if this does not involve any of the means set forth in subparagraph (a) of this article;

(d) "Child" shall mean any person under eighteen years of age.

Article 5 of the Palermo Protocol then requires the member states to criminalize trafficking based on the definition outlined in Article 3; however, many member states' domestic laws reflect a narrower definition than Article 3.[6] Although these nations claim to be obliging Article 5, the narrow laws lead to a smaller portion of people being persecuted for sex trafficking.[6]

United States

After members of Prostitutes Anonymous who were survivors of modern domestic sex trafficking spent 13 years doing TV, radio, public appearances, news interviews, etc. and calling out that this country needed to "'do something' about it" – an internationally recognized definition for sex trafficking was finally established with the Trafficking Act of 2000. It was during the same year the Palermo Protocol was enacted, the United States passed the Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000 (TVPA) to clarify the previous confusion and discrepancies in regards to the criminalizing guidelines of human trafficking.[8] Through this act, sex trafficking crimes were defined as a situation where in which a "commercial sex act is induced by force, fraud, or coercion, or in which the person induced to perform such act has not attained 18 years of age."[9] If the victim is a child under the age of 18 no force, fraud, or coercion needs to be proven based on this legislation.[8] Susan Tiefenbrun, a professor at the Thomas Jefferson School of Law who has written extensively on human trafficking, conducted research on the victims addressed in this act and discovered that each year more than two million women throughout the world are bought and sold for sexual exploitation.[5] In order to clarify previous legal inconsistencies in regards to youth and trafficking, the United States took legal measures to define more varieties of exploitive situations in relation to children.[8] The two terms they defined and focused on were "commercial sexual exploitation of children" and "domestic minor sex trafficking." Commercial sexual exploitation of children (CSEC) is defined as "encompassing several forms of exploitation, including pornography, prostitution, child sex tourism, and child marriage."[8] Domestic minor sex trafficking (DMST) is a term that represents a subset of CSEC situations that have "the exchange of sex with a child under the age of 18, who is a United States (US) citizen or permanent resident, for a gain of cash, goods, or anything of value."[8]

Causes

There is not one simple factor that perpetuates sex trafficking, rather a complex, interconnected web of political, socioeconomic, governmental, and societal factors.[10] Siddharth Kara argues that globalization and the spread of Western Capitalism drive inequality and rural poverty, which are the material causes for sex trafficking.[1] Kara also emphasizes that there are factors on both the supply and demand sides of sex trafficking, which contribute to its continued practice. Natural disasters, sex and gender discrimination, personal problems which increase vulnerability, and cultural norms which discriminate certain populations serve as factors which support the supply side of sex trafficking.[1] In regards to the demand for sex trafficking, Kara believes that the demand for inexpensive labor, strict immigration laws and policies, and the involvement of corrupt government officials in trafficking rings act as promoting factors of the industry.[1] Strict immigration laws are also cited by Susan Tiefenbrun as a key factor in individuals entering this industry because "poor women seeking to better their economic situations by emigration resort to the financial assistance of unscrupulous loan sharks and traffickers."[5]

In Susan Tiefenbrun's work on sex trafficking, she cites high poverty rates, a societal norm for minimal respect for women, a lack of public awareness on this issue, limited educational and economic opportunities for women, and poor laws to prosecute exploiters and traffickers, as the major factors present in the "source countries" of sex trafficking.[5] However, the destination countries to which sex workers are sent tend to be much wealthier compared to the source countries.[5]

As shown in this research and many other papers, sex trafficking is the result of a combination of various factors than the simple desire of individuals wanting to reap the profits from exploiting others through based on the demand for inexpensive sexual acts.[1]

Profile and modus operandi of traffickers

Pimp-controlled trafficking

In pimp-controlled trafficking, the victim is controlled by a single trafficker, sometimes called a pimp. The victim can be controlled by the trafficker physically, psychologically, and/or emotionally. In order to obtain control over their victims, traffickers will use force, drugs, emotional tactics as well as financial means. In certain circumstances, they will even resort to various forms of violence, such as gang rape and mental and physical abuse. Traffickers sometimes use offers of marriage, threats, intimidation, and kidnapping as means of obtaining victims.

A common process is for the trafficker to first gain the trust of the victim, called the grooming stage. They seek to make the victim dependent on them.[11] The trafficker may express love and admiration, make lofty promises such as making the victim a star, offer them a job or an education or buy them a ticket to a new location.[12] The main types of work offered are in the catering and hotel industry, in bars and clubs, modeling contracts, or au pair work. Once the victim is comfortable, the pimp moves to the seasoning stage, where they will ask the victim to perform sexual acts for the pimp, which the victim may do because they believe it is the only way to keep the trafficker's affection. The requests progress from there and it can be difficult for the victim to escape.[11]

Another tactic is for traffickers to kidnap their victims, and then drug them or secure them so they cannot escape.[13] Traffickers may seek out potential victims who are traveling alone, are separated from their group, or seem like they have low self-esteem. They may go to places likes malls where they are more likely to find girls without parents.[14]

Traffickers are using social media at an increasing rate to find victims, research potential victims, control their victims and advertise their victims.[15][16] Traffickers often target people who post things that indicate that they are depressed, have low self-esteem or are angry with their parents.[17] Traffickers also use social media posts to establish patterns and track the locations of potential victims.[18]

After the victim has joined the offender, various techniques are used to restrict the victim's access to communication with home, such as imposing physical punishment unless the victim complies with the trafficker's demands and making threats of harm and even death to the victim and their family.[12] Sometimes, the victims will succumb to the Stockholm Syndrome because their captors will pretend to "love" and "need" them, even going so far as promise marriage and future stability. This is particularly effective with younger victims, because they are more inexperienced and therefore easily manipulated.[19]

In India, those who traffick young girls into prostitution are often women who have been trafficked themselves. As adults they use personal relationships and trust in their villages of origin to recruit additional girls.[20] Also, some (migrating) prostitutes (See: migrant sex work) can become victims of human trafficking because the women know they will be working as prostitutes; however, they are given an inaccurate description by their "boss" of the circumstances. Therefore, they consequently get exploited due to their misconception of what conditions to expect of their sex work in the new destination country.[21][22]

Gang-controlled trafficking

In gang-controlled trafficking, the victim is controlled by more than one person. Gangs are more often turning to sex trafficking as it is seen as safer and more lucrative than drug trafficking. A victim controlled by gang trafficking may be sexually exploited by gang members as well as sold outside of the gang. They may tattoo their victims to show their ownership over them.[11]

Familial trafficking

In familial trafficking, the victim is controlled by family members who allow them to be sexually exploited in exchange for something, such as drugs or money. For example, a mother may allow a boyfriend to abuse a child in exchange for a place to stay. Often, the mother was a victim of human trafficking herself. Usually, it begins with one family member and spreads from there. Familial trafficking may be difficult to detect because they often have a larger degree of freedom, such as going to school. They may not understand that they are being trafficked or may not have a way out.[11]

Forced marriage

A forced marriage is a marriage where one or both participants are married without their freely given consent.[23] Servile marriage is defined as a marriage involving a person being sold, transferred or inherited into that marriage.[24] According to ECPAT, "Child trafficking for forced marriage is simply another manifestation of trafficking and is not restricted to particular nationalities or countries".[25]

A forced marriage qualifies as a form of human trafficking in certain situations. If a woman is sent abroad, forced into the marriage and then repeatedly compelled to engage in sexual conduct with her new husband, then her experience is that of sex trafficking. If the bride is treated as a domestic servant by her new husband and/or his family, then this is a form of labor trafficking.[26]

Survival sex

In survival sex, the victim is not necessarily controlled by a certain person but feels they have to perform sexual acts in order to obtain basic commodities to survive. They are considered a victim of sex trafficking if they are below the age of consent and are legally unable to consent to the sexual acts.[11]

Profile of victims

There is no single profile for victims of human trafficking. Most are women, though it is not uncommon for males to be trafficked as well. Victims are captured then exploited all around the world, representing a diverse range of ages and backgrounds, including ethnic and socioeconomic. However, there is a set group of traits associated with a higher risk of becoming trafficked for sexual exploitation. Persons at risk include homeless and runaway youth, foreign nationals (especially those of lower socioeconomic status), and those who have experienced physical, emotional, or sexual abuse, violent trauma, neglect, poor academic success, and inadequate social skills.[2][27] Also, a study on a group of female sex workers in Canada found that 64 percent of the women had been in the child welfare system as children (this includes foster and group homes).[2] This research conducted by Kendra Nixon illustrates how children in or leaving foster care are at a higher risk of becoming a sex worker.[2]

In the United States, research has illustrated how these qualities hold true for victims, even though none can be labeled as a direct cause.[8] For example, more than 50 percent of domestic minor sex trafficking victims have a history of homelessness.[8] Familial disruptions such as divorce or the death of a parent place minors at a higher risk of entering the industry, but home life in general influences children's risk. In a study of trafficked youth in Arizona, 20 to 40 percent of female victims identified with experiencing abuse of some form (sexual or physical) at home before entering into the industry as a sex slave.[8] For the males interviewed, a smaller proportion, 0 to 30 percent, reported former abuse in the home.[8]

Children are at risk because of their vulnerable characteristics; naïve outlook, size, and tendency to be easily intimidated".[2] The International Labor Organization estimates that of the 20.9 million people who are trafficked in the world (for all types of work) 5.5 million are children.[28] There is no official estimate on the number of children sex workers in the United States, but it is believed that there are approximately 100,000 currently working in the industry.[28]

The main motive of a woman (in some cases, an underage girl) to accept an offer from a trafficker is better financial opportunities for herself or her family. A study on the origin countries of trafficking confirms that most trafficking victims are not the poorest in their countries of origin, and sex trafficking victims are likely to be women from countries with some freedom to travel alone and some economic freedom.[29]

Consequences to victims

Sex trafficked people face similar health consequences to women exploited for labor purposes, people who've experienced domestic violence, and migrant women.[30] Many of the sex workers contract sexual transmitted infections (STIs).[8] In a study conducted by the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, "only one of 23 trafficked women interviewed felt well-informed about sexually transmitted infections or HIV before leaving home."[30] Without knowledge about this aspect of their health, trafficked women may not take the necessary preventative steps and contract these infections and have poor health seeking behavior in the future.[30] The mental health implications range from depression to anxiety to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) due to the abuse and violence victims face from their pimps or "Johns".[8] With such a mindset many individuals develop alcohol or drug addictions and abusive habits.[8] Also, traffickers commonly coerce or force their sex workers to use alcohol or drugs when they are in childhood or adolescence.[2] Many victims use these substances as a coping mechanism or escape which further promotes the rate of addiction in this population.[2] In a 30-year longitudinal study conducted by Dr. Potterat et al., it was determined that the average lifespan for women engaged in prostitution in Colorado Springs was 34 years.[8]

Prevalent regions

Africa

Sex trafficking of women and children is the second most common type of trafficking for export in Africa.[10] In Ghana, "connection men" or traffickers are witnessed regularly at border crossings and transport individuals via fake visas. Women are most commonly trafficked to Belgium, Italy, Lebanon, Libya, the Netherlands, Nigeria, and the United States.[10] Belgium, the Netherlands, Spain, and the United States are also common destination countries for trafficked Nigerian women.[10] In Uganda, the Lord's Resistance Army, traffics individuals to Sudan to sell them as sex slaves.[10]

Asia

The key hubs for both source transportation and destination of the sub-region of Asia include India, Japan, South Korea and Thailand.[10] India is a major hub for trafficked Bangladeshi and Nepali women.[10] In Thailand, 800,000 children under the age of 16 were involved in prostitution in 2004.[31] Also, according to UNICEF and the International Labour Organization there are 40,000 child prostitutes in Sri Lanka.[31] Thailand and Sri Lanka are of the top five countries with the highest rates of child prostitution.[31]

Europe

Europe has the highest number of sex slaves per capita in the world.[32] In general, countries who are members of the European Union are destinations for sex trafficked individuals whereas the Balkans and Eastern Europe are source and transit countries.[10] In 1997 alone as many as 175,000 young women from Russia, as well as the former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, were sold as commodities in the sex markets of the developed countries in Europe and the Americas[33] The European Union reported that from 2010–13 30,146 individuals were identified and registered as human trafficking victims.[34] Of those registered, 69 percent of the victims were sexually exploited and more than 1,000 were children.[34] Although many sex trafficked individuals are from outside of Europe, two-thirds of the 30,146 victims were EU citizens.[34] Despite this high proportion of domestic sex slaves, the most common ethnicities of women who are trafficked to the United Kingdom are Chinese, Brazilian, and Thai.[10]

Combating

History of international legislation

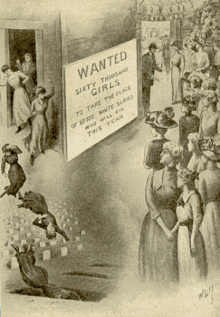

International pressure to address trafficking in women and children became a growing part of the social Reform movement in the United States and Europe during the late nineteenth century. International legislation against the trafficking of women and children began with the conclusion of an international convention in 1901, and the International Agreement for the suppression of the White Slave Traffic in 1904. (The latter was revised in 1910.) These conventions were ratified by 34 countries. The first formal international research into the scope of the problem was funded by American philanthropist John D. Rockefeller, through the American Bureau of Social Hygiene. In 1923, a committee from the bureau was tasked with investigating trafficking in 28 countries, interviewing approximately 5,000 informants and analyzing information over two years before issuing its final report. This was the first formal report on trafficking in women and children to be issued by an official body.[35]

The League of Nations, formed in 1919, took over as the international coordinator of legislation intended to end the trafficking of women and children. An international Conference on White Slave Traffic was held in 1921, attended by the 34 countries that ratified the 1901 and 1904 conventions.[36] Another convention against trafficking was ratified by League members in 1922, and like the 1904 international convention, this one required ratifying countries to submit annual reports on their progress in tackling the problem. Compliance with this requirement was not complete, although it gradually improved: in 1924, approximately 34 percent of the member countries submitted reports as required: this rose to 46 percent in 1929, 52 percent in 1933, and 61 percent in 1934.[37] The 1921 International Convention for the Suppression of the Traffic in Women and Children was sponsored by the League of Nations.

United Nations

The first international protocol dealing with sex slavery was the 1949 UN Convention for the Suppression of the Traffic in Persons and Exploitation of Prostitution of Others.[38] This convention followed the abolitionist idea of sex trafficking as incompatible with the dignity and worth of the human person. Serving as a model for future legislation, the 1949 UN Convention was not ratified by every country, but came into force in 1951. These early efforts led to the 2000 Convention against Transnational Organized Crime, mentioned above. These instruments contain the elements of the current international law on trafficking in humans.

In 2011, the United Nations reported that girl victims made up two-thirds of all trafficked children. Girls constituted 15 to 20 percent of the total number of all detected victims, whereas boys comprised about 10 percent. The UN report was based on official data supplied by 132 countries.

In 2013, a resolution to create the World Day Against Trafficking in Persons was adopted by the United Nations.[39] The first World Day against Trafficking in Persons took place July 30, 2014, and the day is now observed every July 30.[39]

Current international treaties include the Convention on Consent to Marriage, Minimum Age for Marriage, and Registration of Marriages, entered into force in 1964.

In the United States

.jpg)

In 1910, the U.S. Congress passed the White Slave Traffic Act of 1910 (better known as the Mann Act), which made it a felony to transport women across state borders for the purpose of "prostitution or debauchery, or for any other immoral purpose". Its primary stated intent was to address prostitution, immorality, and human trafficking particularly where it was trafficking for the purposes of prostitution, but the ambiguity of "immorality" effectively criminalized interracial marriage and banned single women from crossing state borders for morally wrong acts. In 1914, of the women arrested for crossing state borders under this act, 70 percent were charged with voluntary prostitution. Once the idea of a sex slave shifted from a white woman to an enslaved woman from countries in poverty, the US began passing immigration acts to curtail aliens from entering the country in order to address this issue. (The government had other unrelated motives for the new immigration policies.) Several acts such as the Emergency Quota Act of 1921 and Immigration Act of 1924 were passed to prevent emigrants from Europe and Asia from entering the United States. Following the banning of immigrants during the 1920s, human trafficking was not considered a major issue until the 1990s.[40][41]

Act 18 U.S.C. § 1591, or the Commercial Sex Act, the US makes it illegal to recruit, entice, obtain, provide, move or harbor a person or to benefit from such activities knowing that the person will be caused to engage in commercial sex acts where the person is under 18 or where force, fraud or coercion exists.[42][43]

Under the Bush Administration, fighting sex slavery worldwide and domestically became a priority with an average of $100 million spent per year, which substantially outnumbers the amount spent by other countries. Before President Bush took office, Congress passed the Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act of 2000 (TVPA). The TVPA strengthened services to victims of violence, law enforcement's ability to reduce violence against women and children, and education against human trafficking. Also specified in the TVPA was a mandate to collect funds for the treatment of sex trafficking victims that provided them with shelter, food, education, and financial grants. Internationally, the TVPA set standards that governments of other countries must follow in order to receive aid from the U.S. to fight human trafficking. Once George W. Bush took office in 2001, restricting sex trafficking became one of his primary humanitarian efforts. The Attorney General under President Bush, John Ashcroft, strongly enforced the TVPA. The Act was subsequently renewed in 2004, 2006, and 2008. It established two stipulations an applicant has to meet in order to receive the benefits of a T-Visa. First, a trafficked victim must prove/admit to being trafficked and second must submit to prosecution of his or her trafficker. In 2011, Congress failed to re-authorize the Act. The State Department publishes an annual Trafficking in Persons Report, which examines the progress that the U.S. and other countries have made in destroying human trafficking businesses, arresting the kingpins, and rescuing the victims.[44][45][46]

Council of Europe

Complementary protection is ensured through the Council of Europe Convention on the Protection of Children against Sexual Exploitation and Sexual Abuse (signed in Lanzarote, 25 October 2007). The Convention entered into force on 1 July 2010.[47] As of December 2016, the Convention has been ratified by 42 states, with another 5 states having signed but not yet ratified.[48] The goal of the Convention is to provide the framework for an independent and effective monitoring system that holds the member states accountable for addressing human trafficking and providing protecting to victims.[49] To monitor the implementation of this act, the Council of Europe established the Group of Experts on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings (GRETA).[50] The Convention address the structure and purpose of GRETA and holds the group accountable to publish reports evaluating the measures taken by the states who have signed the Convention.[50]

Other government actions

Actions taken to combat human trafficking vary from government to government.[51] Some government actions include:

- introducing legislation specifically aimed at criminalizing human trafficking

- developing co-operation between law enforcement agencies and non-government organizations (NGOs) of numerous nations

- raising awareness of the issue

Raising awareness can take three forms. First, governments can raise awareness among potential victims, particularly in countries where human traffickers are active. Second, they can raise awareness amongst the police, social welfare workers and immigration officers to equip them to deal appropriately with the problem. And finally, in countries where prostitution is legal or semi-legal, they can raise awareness amongst the clients of prostitution so that they can watch for signs of human trafficking victims. Methods to raise general awareness often include television programs, documentary films, internet communications, and posters.[52]

Criticism

Many countries have come under criticism for inaction, or ineffective action. Criticisms include the failure of governments to properly identify and protect trafficking victims, enactment of immigration policies which potentially re-victimize trafficking victims, and insufficient action in helping prevent vulnerable populations from becoming trafficking victims. A particular criticism has been the reluctance of some countries to tackle trafficking for purposes other than sex.

Non-governmental organizations (NGOs)

Many NGOs work on the issue of sex trafficking. One major NGO is the International Justice Mission (IJM). IJM is a U.S.-based non-profit human rights organization that combats human trafficking in developing countries in Latin America, Asia, and Africa. IJM states that it is a "human rights agency that brings rescue to victims of slavery, sexual exploitation, and other forms of violent oppression." It is a faith-based organization since its purported goal is to "restore to victims of oppression the things that God intends for them: their lives, their liberty, their dignity, the fruits of their labor."[53] The IJM receives over $900,000 from the US government.[54] The organization has two methods for rescuing victims: brothel raids in cooperation with local police, and "buy bust" operations in which undercover agencies pretend to purchase sex services from an underage girl. After the raid and rescue, the women are sent to rehabilitation programs run by NGOs (such as churches) or the government.

There are also national Non-governmental organizations working on the issue of human trafficking, including sex trafficking. In Kenya for example, Awareness Against Human Trafficking (HAART) works on ending all human trafficking in the country.[55] HAART has also participated in the UNANIMA International Stop the Demand campaign [56]

Campaigns and initiatives

In 1994, Global Alliance Against Traffic in Women was established to combat trafficking in women on any grounds. It is an alliance of more than 100 non-governmental organizations from Africa, Asia, Europe, Latin America, the Caribbean and North America.[57] The Demi and Ashton (DNA) Foundation was created by celebrity humanitarians Demi Moore and Ashton Kutcher in 2009 in their efforts to fight human trafficking (specifically focusing on sex trafficking of children) in the U.S. In September 2010, the pair announced the launch of their "Real Men Don't Buy Girls" campaign to combat child sex trafficking alongside other Hollywood stars and technology companies such as Microsoft, Twitter, and Facebook. "Real Men Don't Buy Girls" is based on the idea that high-profile men speaking out against child sex trafficking can help reduce the demand for young girls in the commercial sex trade. The popular TV channel MTV started a campaign to combat sex trafficking. The initiative called MTV EXIT (End Exploitation and Trafficking) is a multimedia initiative produced by MTV EXIT Foundation (formerly known as the MTV Europe Foundation) to raise awareness and increase prevention of human trafficking.[58][59]

Another campaign is the A21 Campaign, Abolishing Injustice in the 21st Century, which focuses on addressing human trafficking through a holistic approach.[60] They provide potential victims with the education and valuable information on how to best reduce their likelihood of being trafficked through strategies that reduce their vulnerability. The organization also provides safe environments for victims and runs restoration programs in their aftercare facilities.[60] In addition, they provide legal council and representation to victims so they can prosecute their traffickers. Another key component of the campaign is to help influence legislation in order to enact more comprehensive laws that place more traffickers in prison.[60]

The Not for Sale (organization) Campaign works in the United States, Peru, the Netherlands, Romania, Thailand, South Africa, and India to help victims of human trafficking. In 2013 alone, they provided 4,500 services to 2,062 individuals.[61] The vast majority of victims who received assistance were from the Netherlands and the number of victims served increased by 42 percent from 2012. The campaign allocates the majority of their funds to providing victims health and nutritional care and education. Not for Sale provides a safe shelter for victims and empowers them with life skills and job training.[61] This helps trafficked individuals re-enter into the workforce through a dignified form of work. In the organization's 2013 Annual Impact Report, it was determined that 75 percent of the victims had been sexually exploited.[62]

While globalization fostered new technologies that may exacerbate sex trafficking, technology can also be used to assist law enforcement and anti-trafficking efforts. A study was done on online classified ads surrounding the Super Bowl. A number of reports have noticed increase in sex trafficking during previous years of the Super Bowl.[63] For the 2011 Super Bowl held in Dallas, Texas, the Backpage website for the Dallas area experienced a 136 percent increase on the number of posts in the Adult section that Sunday. Typically, Sundays were known to be the day of the week with the lowest amount of posts in the Adult section. Researchers analyzed the most salient terms in these online ads and found that most commonly used words suggested that many escorts were traveling across state lines to Dallas specifically for the Super Bowl. Also, the self-reported ages were higher than usual which conveys that an older population of sex workers were drawn to the event, but since these are self-reported the data is not reliable. Twitter was another social networking platform studied for detecting sex trafficking. Digital tools can be used to narrow the pool of sex trafficking cases, albeit imperfectly and with uncertainty.[64]

'End Demand'

End Demand refers to the strategy and efforts of different institutions that seek to end sex trafficking by eliminating and criminalizing the demand for commercial sex. End Demand is very popular in some countries including the United States and Canada.[65] Proponents of the End Demand strategy support initiatives such as "John's schools" that rehabilitate johns, increased arrests of johns, and public shaming (e.g. billboards and websites that publicly name johns who were caught).[65][66][67] John's Schools were pioneered in San Francisco in 1995 and now used in many cities across the U.S. as well as other countries such as the UK and Canada. Some compare John's Schools programs to driver's safety courses, because first offenders can pay a fee to attend class(es) on the harms of prostitution, and upon completion, the charges against the john will be dropped. Another initiative that seeks to end demand is the cross-country tour "Ignite the Road to Justice," launched by the 2011 Miss Canada, Tara Teng. Teng's initiative circulates a petition to end the demand for commercial sex that drives prostitution and sex trafficking. End Demand efforts also include large-scale public awareness campaigns. Campaigns have started in Sweden, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Atlanta, Georgia. The Atlanta campaign in 2006 was titled "Dear John," and ran ads in local media reaching out to potential johns to discourage them from buying sex. Massachusetts and Rhode Island also had legislative efforts that criminalized prostitution and increased end demand efforts by targeting johns.[65]

Sweden criminalized the buying of sex in 1999, and Norway and Iceland later introduced similar laws that are aimed at combating trafficking.[68]

See also

- Sexual exploitation

- Human trafficking

- Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, especially Women and Children

- Transnational efforts to prevent human trafficking

- Migrant sex work

- Sex tourism

- Karayuki-san

- Forced prostitution

- Exploitation of labour

- Trafficking of children

- Child laundering

- Prostitution

- People smuggling

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Kara, Siddharth (2009). Sex Trafficking: Inside the Bus@$iness of Modern Slavery. Columbia University Press.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Hammond, Gretchen; McGlone, Mandy (March 22, 2014). "Entry, Progression, Exit, and Service Provision for Survivors of Sex Trafficking: Implications for Effective Interventions". Global Social Welfare. 1: 157–168. doi:10.1007/s40609-014-0010-0., citing Maria Beatriz Alvarez, Edward J. Alessi (May 2012). "Human trafficking is more than sex trafficking and prostitution: implications for social work". Affilia. 27 (2): 142–152. doi:10.1177/0886109912443763.

- 1 2 "U.N.: 2.4 million human trafficking victims". USA Today. USA Today. 4 April 2012. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ↑ "ILO 2012 Global estimate of forced labour - Executive summary" (PDF). International Labour Organization. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Tiefenbrun, Susan (2002). "The Saga of Susannah A U.S. Remedy for Sex Trafficking in Women: The Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act of 2000". Utah Law Review. 107.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Dempsey, Michelle Madden; Hoyle, Carolyn; Bosworth, Mary (2012). "Defining Sex Trafficking in International and Domestic Law: Mind the Gaps". Emory International Law Review. Villanova Law/Public Policy Research Paper No. 2013-3036. 26 (1).

- ↑ United Nations (2012). "Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children, Supplementing The United Nations Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime". Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Lew, Candace (July 2012). "Sex Trafficking of Domestic Minors in Phoenix, Arizona: A Research Project" (PDF). Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ↑ United States Government. "Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act of 2000" (PDF). U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Commonwealth Secretariat (2004). Gender and Human Rights in the Commonwealth: Some critical issues for action in the decade 2005-2015. Commonwealth Secretariat.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Shared Hope International: Rapid Assessment

- 1 2 "Human Trafficking and the Internet* (*and Other Technologies, too) - Judicial Division". Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- ↑ "Truckers Take The Wheel In Effort To Halt Sex Trafficking". Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- ↑ "TOP FIVE: Hot Spots for Human Trafficking - The A21 Campaign". Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- ↑ "How the internet and social media impact sex trafficking". 7 April 2014. Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- ↑ Human Trafficking Online: The Role of Social Networking Sites and Online Classifieds

- ↑ "Primary Research: Diffusion of Technology-Facilitated Human Trafficking · Technology & Human Trafficking". Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- ↑ Scott, Eric. "Careless use of social media increases human trafficking rate in Florida". Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- ↑ Walker-Rodriguez, Amanda; Hill, Rodney (March 2011). "Human Sex Trafficking". FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin. Retrieved 7 October 2013.

- ↑ Alyson Warhurst; Cressie Strachan; Zahed Yousuf; Siobhan Tuohy-Smith (August 2011). "Trafficking A global phenomenon with an exploration of India through maps" (PDF). Maplecroft. p. 51. Retrieved December 25, 2012.

- ↑ "Research based on case studies of victims of trafficking in human beings in 3 EU Member States, i.e. Belgium, Italy and The Netherlands" (PDF). Commission of the European Communities, DG Justice & Home Affairs. 2001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-06-26. Retrieved 2008-10-05.

- ↑ "Media Conference for Announcing Role of Dewi Hughes 28 May 2003" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-03-22.

- ↑ "BBC - Ethics - Forced Marriages: Introduction". bbc.co.uk.

- ↑ "Forced and servile marriage in the context of human trafficking". aic.gov.au.

- ↑ http://www.ecpat.org.uk/sites/default/files/forced_marriage_ecpat_uk_wise.pdf

- ↑ "Forced Marriage and the Many Faces of Human Trafficking". theahafoundation.org.

- ↑ "The Victims". www.traffickingresourcecenter.org. National Human Trafficking Resource Center. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- 1 2 Polaris Project http://www.polarisproject.org/human-trafficking/overview. Retrieved 28 April 2015. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Rao, Smriti; Presenti, Christina (2012). "Understanding Human Trafficking Origin: A Cross-Country Empirical Analysis". Feminist Economics. 18 (2): 231–263 [233–234]. doi:10.1080/13545701.2012.680978.

- 1 2 3 Zimmerman, Cathy (2003). "The health risks and consequences of trafficking in women and adolescents: Findings from a European study". London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine.

- 1 2 3 Iaccino, Ludovica (February 6, 2014). "Top Five Countries with Highest Rates of Child Prostitution". International Business Times. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- ↑ Roux, Malin (April 27, 2015). "The Movement For Fair Sex - Against Trafficking and Stop Sex Exploitation in Europe". Real Stars. Real Stars.

- ↑ Johanna Granville, "From Russia without Love: The ‘Fourth Wave’ of Global Human Trafficking", Demokratizatsiya, vol. 12, no. 1 (Winter 2004): pp. 147-155.

- 1 2 3 "Trafficking harms 30,000 in EU - most in sex trade". BBC. BBC. October 17, 2014. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- ↑ Berkovitch, Nitzka (1999). From Motherhood to Citizenship: Women's Rights and International Organizations. JHU Press. pp. 75–6. ISBN 9780801860287.

- ↑ Berkovitch, Nitzka (1999). From Motherhood to Citizenship: Women's Rights and International Organizations. JHU Press. p. 75. ISBN 9780801860287.

- ↑ Berkovitch, Nitzka (1999). From Motherhood to Citizenship: Women's Rights and International Organizations. JHU Press. p. 81. ISBN 9780801860287.

- ↑ http://polis.osce.org/library/f/3655/2833/UN-USA-RPT-3655-EN-Text%20of%20the%20Convention.pdf

- 1 2 "Feminist Wire Daily Newsbriefs: U.S. and Global News Coverage". Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- ↑ Candidate, Jo Doezema Ph.D. "Loose women or lost women? The re-emergence of the myth of white slavery in contemporary discourses of trafficking in women." Gender issues 18.1 (1999): 23–50.

- ↑ Donovan, Brian. White slave crusades: race, gender, and anti-vice activism, 1887-1917. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2006.

- ↑ "Stop Sex Trafficking.". Retrieved 2010-03-10.

- ↑ "Victims Of Trafficking And Violence Protection Act of 2000." (PDF).

- ↑ Soderlund, Gretchen. "Running from the rescuers: new US crusades against sex trafficking and the rhetoric of abolition." nwsa Journal 17.3 (2005): 64-87.

- ↑ Feingold, David A. "Human trafficking." Foreign Policy (2005): 26-32.

- ↑ Horning, A.; Thomas, C.; Henninger, A. M.; Marcus, A. (2014). "The Trafficking in Persons Report: a game of risk". International Journal of Comparative and Applied Criminal Justice. 38 (3).

- ↑ "Liste complète". Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- ↑ http://www.coe.int/en/web/conventions/full-list/-/conventions/treaty/201/signatures

- ↑ Council of Europe (2005). Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings (PDF). Council of Europe. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- 1 2 Council of Europe. "About GRETA". Council of Europe. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- ↑ "Cho, Seo-Young, Axel Dreher and Eric Neumayer (2011), The Spread of Anti-trafficking Policies - Evidence from a New Index, Cege Discussion Paper Series No. 119, Georg-August-University of Goettingen, Germany." (PDF). Retrieved 2011-11-13.

- ↑ "Global TV Campaign on Human Trafficking". UN Office on Drugs and Crime. 2003. Archived from the original on 2007-10-06. Retrieved 2008-10-05. (archived from the original on 2007-10-0-6)

- ↑ Aziza Ahmed and Meena Seshu (June 2012). ""We Have the Right Not to Be 'rescued'…"*: When Anti-Trafficking Programmes Undermine the Health and Well-Being of Sex Workers". Anti Trafficking Review. Global Alliance Against Traffic in Women. 1: 149-19.

- ↑ "USAID Contracts with Faith Based Organizations". Boston.com. Retrieved March 14, 2012.

- ↑ Awareness against human trafficking HAART Kenya http://haartkenya.org

- ↑ UNANIMA International Stop the Demand http://www.unanima-international.org/what-we-do/campaigns/stop-the-demand

- ↑ "Home - The Global Alliance Against Traffic in Women (GAATW)". Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- ↑ "Staying Alive Foundation". Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- ↑ "MTV EXIT Foundation (End Exploitation and Trafficking) - Corporate NGO partnerships". Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Our Solution". The A21 Campgain. The A21 Campgain. Retrieved April 28, 2015.

- 1 2 "Our Strategy". Not for Sale. Retrieved April 28, 2015.

- ↑ "2013 Annual Impact Report". Not for Sale. Retrieved April 27, 2015.

- ↑ "Michelle Goldberg, "The Super Bowl of Sex Trafficking," Newsweek, January 30, 2011.".

- ↑ Latonero, Mark. "Human Trafficking Online: The Role of Social Networking Sites and Online Classifieds." USC Annenberg Center on Communication Leadership & Policy. Available at SSRN 2045851 (2011).

- 1 2 3 Berger, Stephanie M (2012). "No End In Sight: Why The "End Demand" Movement Is The Wrong Focus For Efforts To Eliminate Human Trafficking". Harvard Journal of Law & Gender. 35 (2): 523–570.

- ↑ Wortley, S.; Fischer, B.; Webster, C. (2002). "Vice lessons: A survey of prostitution offenders enrolled in the Toronto John School Diversion Program". Canadian Journal of Criminology. 3 (3): 227–248.

- ↑ Monto, Martin A.; Garcia, Steve (2001). "Recidivism Among the Customers of Female Street Prostitutes: Do Intervention Programs Help?". Western Criminology Review. 3 (2).

- ↑ Max Waltman: Criminalize Only the Buying of Sex New York Times, 20 April 2012