Sergei Rachmaninoff

Sergei Vasilievich Rachmaninoff (Russian: Серге́й Васи́льевич Рахма́нинов, tr. Sergéj Vasíl'evič Rahmáninov; IPA: [sʲɪrˈɡʲej rɐxˈmanʲɪnəf];[nb 1] 1 April [O.S. 20 March] 1873[nb 2] – 28 March 1943) was a Russian pianist, composer, and conductor of the late-Romantic period, some of whose works are among the most popular in the classical repertoire. He is regarded as one of the major composers of the 20th century.

Born into a musical family, Rachmaninoff took up the piano at age four. He graduated from the Moscow Conservatory in 1892 and had composed several piano and orchestral pieces by this time. In 1897, following the critical reaction to his Symphony No. 1, Rachmaninoff entered a four-year depression and composed little until successful therapy allowed him to complete his enthusiastically received Piano Concerto No. 2 in 1901. After the Russian Revolution, Rachmaninoff and his family left Russia and resided in the United States, first in New York City. Demanding piano concert tour schedules caused his output as composer to slow tremendously; between 1918 and 1943, he completed just six compositions, including Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, Symphony No. 3, and Symphonic Dances. In 1942, Rachmaninoff moved to Beverly Hills, California. He acquired U.S. citizenship a month before his death from advanced melanoma.

Early influences of Tchaikovsky, Rimsky-Korsakov, Balakirev, Mussorgsky, and other Russian composers gave way to a personal style notable for its song-like melodicism, expressiveness and his use of rich orchestral colors.[3] The piano is featured prominently in Rachmaninoff's compositional output, and through his own skills as a performer he explored the expressive possibilities of the instrument.

Biography

Early years

Rachmaninoff was born at a family estate in the Novgorod province in north-western Russia. It is unclear if he was born in the estate of Oneg, near Veliky Novgorod, or Semyonovo, near Staraya Russa, but the composer would cite Oneg as his birth place in his adult life.[4][5]

The Rachmaninoff family was an old Russian aristocratic family, which according to the 17th-century Velvet Book, a register of Russia's most illustrious families, was of Romanian origin, descending from Vasile, nicknamed Rachmaninov, a son of Moldavian Prince Stephen the Great.[6]

The Rachmaninoffs had strong musical and military leanings. His father, Vasily Arkadyevich Rachmaninoff (1841–1916), was an amateur pianist and army officer, who had taken lessons from John Field.[7] He married Lyubov Petrovna Butakova (1853–1929), the daughter of a wealthy army general who gave her five estates as part of her dowry. The couple had three sons and three daughters, Rachmaninoff being their fourth child.[8]

Rachmaninoff began piano and music lessons organised by his mother at the age of four.[4] She became impressed with her son's musical ability to recite entire passages from memory without playing a wrong note. News of the young composer's gift reached his paternal grandfather Arkady who suggested to hire Anna Ornatskaya, a teacher from Saint Petersburg and friend of Rachmaninoff's mother, to live with the family and begin formal lessons, in 1880. Rachmaninoff later dedicated "Spring Waters", Song No. 32 to Ornatskaya.[9] In 1882, Rachmaninoff's father had to auction off their Oneg estate due to his financial incompetence—the family's five estates had been reduced to one. Rachmaninoff described his father as "a wastrel, a compulsive gambler, a pathological liar, and a skirt chaser".[10][11] The family moved to a small flat in Saint Petersburg.[12]

When Rachmaninoff's course of lessons with Ornatskaya neared its end, she arranged for him to study music at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory, which he entered at age ten, in 1883. That year, his sister Sofia died of diphtheria and his father left the family, with their approval, for Moscow.[8] His maternal grandmother stepped in to help raise the children with particular focus on their spiritual life, regularly taking Rachmaninoff to Russian Orthodox church services where he first experienced liturgical chants and church bells, two features he would incorporate in his future compositions.[12]

In 1885, Rachmaninoff's sister Yelena died of pernicious anemia at eighteen, before she was to start training with the Bolshoi Theatre company. She was an important musical influence to Rachmaninoff who introduced him to the works of Tchaikovsky. As a respite, his grandmother took him to a farm retreat by the Volkhov River where he developed a love for rowing.[8] Rachmaninoff began to adopt a relaxed attitude to his studies, failing his general education classes and changing his report cards in what fellow Russian composer Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov later called a period of "purely Russian self-delusion and laziness".[13] In 1885, Rachmaninoff performed at events at the Moscow Conservatory often attended by the Grand Duke Konstantin and other notable figures, but he failed his spring exams, leaving Ornatskaya to notify his mother that his admission to further education might be revoked if his poor performance continued.[8] His mother then consulted with her nephew Alexander Siloti (by marriage), an accomplished pianist and student of Franz Liszt, who praised Rachmaninoff for his piano and listening skills. Siloti recommended he attend the Moscow Conservatory and receive lessons from his former teacher, the more strict Nikolai Zverev,[14][15] which lasted from 1885 to 1888.[16]

Moscow Conservatory and early compositions

Rachmaninoff found his first romance in the neighbouring Skalon family with Vera, the youngest of three daughters. However, her mother objected and forbade Rachmaninoff to write to her, leaving him to correspond with her older sister Natalia. It is from these letters that many of Rachmaninoff's early compositions can be traced.[14] During his final studies at the Moscow Conservatory he completed the Youth Symphony, a one-movement symphonic piece, Prince Rostislav, a symphonic poem, and The Rock (Op. 7), a fantasia for orchestra.[8] In the spring of 1891, he passed his final piano exams at the Moscow Conservatory with honours. He then moved to Ivanovka estate with Siloti and began composing his Op. No. 1, the Piano Concerto No. 1.

On 11 February 1892, Rachmaninoff performed his first independent concert where he premiered his Trio élégiaque No. 1 with violinist David Kreyn and cellist Anatoliy Brandukov. This was followed by a performance of the first movement of his Piano Concerto No. 1 on 29 March.[17] His final composition exercise for the conservatory was Aleko, a one-act opera based on the poem The Gypsies by Alexander Pushkin, which Rachmaninoff completed while staying with his father in Moscow.[18] It was first performed on 19 May 1892 at the Bolshoi Theatre; he thought the work was "sure to fail", but it was so successful, the theatre agreed to produce it, starring opera singer Feodor Chaliapin who would become a lifelong friend of the composer.[19][14] The piece earned him a Great Gold Medal, awarded only twice before to Sergei Taneyev and Arseny Koreshchenko.[14] On 29 May 1892, the Conservatory issued Rachmaninoff with a diploma, allowing him to officially style himself as a "Free Artist."[8]

Rachmaninoff continued to compose, publishing at this time his Six Songs (Op. 4) and Two Pieces (Op. 2). He spent the summer of 1892 on the estate of Ivan Konavalov, a rich landowner in the Kostroma Oblast, and moved back with the Satins in the Arbat District.[8] His publisher was slow in paying, so Rachmaninoff took an engagement at the Moscow Electrical Exhibition, where he premiered his landmark Prelude in C-sharp minor (Op. 3, No. 2),[20] a composition that formed a part of five pieces titled Morceaux de fantaisie, that was well received and became one of his most enduring pieces.[21][22]

Rachmaninoff spent the summer of 1893 with friends in Lebedyn, where he composed Fantaisie-Tableaux (Suite No. 1, Op. 5) and Morceaux de salon (Op. 10).[23] In September, he published Six Songs (Op. 8), a group of songs set to translations by Aleksey Pleshcheyev of Ukrainian and German poems.[24] Rachmaninoff returned to Moscow, where Tchaikovsky agreed to conduct The Rock, a piece that he grew fond of, for an upcoming tour across Europe. Rachmaninoff then took an excursion to Kiev to conduct several performances of Aleko. It was during his trip when, on 25 October, Rachmaninoff received the news of Tchaikovsky's death from cholera on 6 November [O.S. 25 October] 1893.[25] That day, he began work on his Trio élégiaque No. 2 for piano, violin and cello as a tribute to the composer. It was completed on 15 December.[26] The music's aura of gloom reveals the depth and sincerity of Rachmaninov's grief for his idol.[27] Its debut performance occurred at the first concert devoted to compositions by Rachmaninoff on 31 January 1894.[26]

Symphony No. 1, depression and conducting debut

In late 1895, to help improve his depleting finances, Rachmaninoff agreed to a three-month concert tour across Russia with a program shared by Teresina Tua, an Italian violinist. He did not enjoy the experience, and quit the tour early while sacrificing his performance fees which caused him to pawn his watch given to him by Zverev.[28] In September 1895, before the tour started, Rachmaninoff completed his Symphony No. 1 (Op. 13), a work conceived in January based on chants heard in Russian Orthodox church services.[28] He worked so hard on the piece, he could not settle himself into composing again until he heard the piece performed.[29] However, Rachmaninoff had to resume work in October 1896 order to recoup his losses after "a rather large sum of money" that was not his, was stolen during a train journey. Among these were included Six Choruses for Women's or Children's Voices (Op. 15) and Moments Musicaux (Op. 16), his final completed composition for several months.[30]

The Symphony No. 1 premiered on 28 March 1897 in one of a long-running series of Russian Symphony Concerts. The piece was brutally panned by critic and nationalist composer César Cui, who likened it to a depiction of the ten plagues of Egypt, suggesting it would be admired by the "inmates" of a music conservatory in Hell.[31] The deficiencies of the performance, conducted by Alexander Glazunov, were not commented on by critics,[27] but according to a memoir from Alexander Ossovsky, a close friend of Rachmaninoff,[32][33] Glazunov made poor use of rehearsal time, and the concert's program itself, which contained two other premières, was also a factor. Other witnesses suggested that Glazunov, an alcoholic, may have been drunk, although this was never intimated by Rachmaninoff.[34][35] Following the reaction to his first symphony, Rachmaninoff wrote in May 1897 that "I'm not at all affected" by its lack of success or critical reaction, but felt "deeply distressed and heavily depressed by the fact that my Symphony ... did not please me at all after its first rehearsal." He thought its performance was poor, particularly Glazunov's contribution.[36] The piece was not performed for the rest of Rachmaninoff's life, but he revised it into a four-hand piano arrangement in 1898.

Rachmaninoff fell into a depression that lasted for three years, during which he composed almost nothing. He compared this time "Like the man who had suffered a stroke and for a long time had lost the use of his head and hands",[37] and made a living by giving piano lessons.[38] A stroke of good fortune came from Savva Mamontov, a Russian industrialist and founder of the Moscow Private Russian Opera Company, who offered Rachmaninoff the post of assistant conductor for the 1897–98 season. The cash-strapped composer accepted, conducting Samson and Delilah by Camille Saint-Saëns as his first on 12 October 1897.[39] In January 1899, Rachmaninoff attempted composition for the first time and completed two short piano pieces, Morceau de Fantaisie and Fughetta in F major. Two months later, he travelled to London for the first time to perform and conduct which earned positive reviews.[40]

During his time at the opera company, Rachmaninoff became engaged to his first cousin Natalia Satina, a fellow pianist whom he had known since childhood. However, the Orthodox church and Satina's parents opposed their announcement, thwarting their plans for marriage. Rachmaninoff's depression worsened in late 1899 following an unproductive summer; he composed one song, "Fate", which later made up his Twelve Songs (Op. 21) and left compositions for a proposed return visit to London unfulfilled.[41]

Therapy and recovery

By 1900, Rachmaninoff had become so self-critical that composing became near impossible. His family and friends decided to seek professional help, to which Rachmaninoff agreed without resistance.[42] In January, he began a three-month daily course of hypnotherapy and psychotherapy with physician and amateur musician Nikolai Dahl. Dahl structured his sessions to help the composer's sleep patterns, improve his mood and appetite during the day, and reignite the desire to compose. With further support from those close around him, Rachmaninoff felt "new musical ideas began to stir" within him and made a successful return to composing in the summer.[43] His first major completed work, the Piano Concerto No. 2, is dedicated to Dahl. Rachmaninoff was the soloist at the premiere of the first and last movements on 2 December 1900[43] and the entire piece in 1901,[44] which was enthusiastically received. Rachmaninoff's spirits grew when, after three years of engagement, he finally married Satina on 29 April 1902[45] at a ceremony held in an army chapel in a Moscow suburb. The couple used the family's military background to circumvent the church as Rachmaninoff was not a regular church attendee and avoided confession, two things a priest had to confirm on a signed certificate.[46] They settled in Moscow where they had two daughters, Irina Sergeievna Rachmaninova (1903–1969) and Tatiana Sergeievna Rachmaninova (1907–1961).[47][48][49]

In 1904, Rachmaninoff agreed to a stint as conductor at the Bolshoi Theatre where he conducted his two new operas, The Miserly Knight and Francesca da Rimini,[50] in January 1906. His position came to an end following the political unrest surrounding the 1905 Russian Revolution, resulting in his resignation in February 1906, after which he and his family went on holiday in Italy[51] until July that year. In 1906, Rachmaninoff moved his family to Dresden, Germany and spent his time intensively composing, only to return to the Ivanovka family estate in the summer.[52] His sense of self-worth as a symphonist was regained following the enthusiastic reaction to the premiere of his Symphony No. 2 in early 1908, where he was awarded with his second Glinka Award ten months later for 1,000 roubles.[53] From 1909 to 1910, Rachmaninoff embarked on his first tour of North America, playing the piano and conducting across 26 performances which marked the composer's first solo piano recitals without another performer on the program. His first recital occurred at Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts on 4 November 1909 and his first with an orchestra followed on 8 November. He conducted the Philadelphia Orchestra for his conducting debut, and premiered his Piano Concerto No. 3 (Op. 30) with the New York Symphony Orchestra.[54] The tour made him a popular figure in America; however, he was unhappy and declined subsequent job offers. He declined to be the conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra as such a long absence from his home and family in Russia seemed "absurd".[55][56]

In 1912, Rachmaninoff quit his position as vice-president of the Russian Musical Society in protest when he heard that a musician in an administrative post with the society was dismissed on the grounds that the musician was Jewish.[57] Rachmaninoff biographer Sergei Bertensson wrote that Rachmaninoff took his position in the society seriously, "and for Rachmaninoff 'seriously' meant with moral as well as artistic seriousness: these were really fused in him."[57] Soon after his resignation, Rachmaninoff was exhausted from overworking and took his family on holiday in Switzerland and Rome, during which he worked on The Bells, but the holiday was cut short when his two daughters contracted typhoid and were treated in Berlin as he lacked trust in the Italian doctors. Rachmaninoff conducted the premiere of The Bells in Saint Petersburg in November 1913. He completed his All-Night Vigil (Op. 37) in 1915 after he witness a performance of an earlier choral work, Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom (Op. 31), and felt disappointed with the composition. He handed it to Taneyev to correct any errors in its polyphony, but it was returned unaltered with complements. It was received so warmly at its premiere in Moscow in aid of war relief that four additional performances were quickly scheduled.[58] The early death of Alexander Scriabin in 1915, a good friend and fellow student at the Moscow Conservatory, affected Rachmaninoff so deeply that he learned a selection of his piano compositions and completed a concert tour devoted to Scriabin's music to raise funds for his widow.[59] That summer, during a vacation in Finland, Rachmaninoff learned of Taneyev's death, a loss which, along with his father's passing that year, affected him greatly.[60]

Emigration to the United States

The day the Russian Revolution of February 1917 began in Saint Petersburg, Rachmaninoff performed a piano recital in Moscow in aid of wounded Russian soldiers who had fought in the war. He supported the political changes and donated his fee to charity.[61] Following a break with his family in the more peaceful Simeiz, Crimea in August, Rachmaninoff performed at a concert the following month at Yalta. It was his final performance in Russia, before events surrounding the Revolution of October 1917 marked the end of Russia as the composer had known it.[62] As a member of the Russian bourgeoisie, he did not support Bolshevism, neither did his father manage to keep up with the aristocratic circles he had been born into, so that in due course came the humiliation of selling the family estate; then Rachmaninoff’s own estate, Ivanovka, was seized by the Leninist regime in 1917. At the height of such turmoil, Rachmaninoff received an offer to perform ten piano recitals across the peaceful Scandinavia,[63] which he used as an excuse to quickly obtain permits for his family to leave the country. On 22 December 1917, they left on an open sled, travelling north through Finland and on to Helsinki with some money, a few notebooks with sketches of compositions, and two orchestral scores; the first Act of his unfinished opera Monna Vanna and Rimsky-Korsakov's opera The Golden Cockerel. They reached safety in Stockholm, Sweden and, in early 1918, settled in Copenhagen, Denmark where Rachmaninoff worked as a concert pianist, practising exhaustively to improve his technique and learning further compositions to play. The tour lasted from February to July 1918.[64]

With the war continuing across Europe throughout 1918, Rachmaninoff planned his future; he could stay and continue performing and composing, or move once more. Late in the year, he once again received an offer to become conductor of the Boston and Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, but declined. As composing would not pay enough to support himself, Rachmaninoff now saw performing in America as the best solution to his growing financial concerns. On 1 November 1918, the family boarded a boat in Oslo, Norway bound for New York City, arriving eleven days later.[65] They settled in 505 West End Avenue and Rachmaninoff accepted a piano from Steinway as a gift, and acquired Charles Ellis as his agent, who secured him forty performances across the following four months. The family recreated the atmosphere of their Ivanovka estate at their new home, entertaining Russian guests, employing Russian servants, and observing Russian customs.[66] In 1920, Rachmaninoff signed a recording contract with the Victor Talking Machine Company which earned him some much-needed income. He became a member of the board of directors for the Tolstoy Foundation Center in Valley Cottage, New York.

Rachmaninoff sought the company of fellow Russian musicians and befriended pianist Vladimir Horowitz; their first meeting, arranged by Steinway artist representative Alexander Greiner, took place in the basement of Steinway Hall in New York City on 8 January 1928, four days prior to Horowitz's debut at Carnegie Hall playing Tchaikovsky's Piano Concerto No. 1, which Rachmaninoff intended to attend, as he had heard positive reviews of Horowitz's playing of his own Piano Concerto No. 3; and he expressed a wish to accompany Horowitz in a performance of the piece.[67] For Horowitz, the opportunity represented a dream come true as Rachmaninoff was "the musical god of my youth ... the most unforgettable impression of my life!"[68] About the pianist's interpretation of Rachmaninoff's own third concerto, the composer said to Abram Chasins that Horowitz "swallowed it whole ... he had the courage, the intensity, the daring."[67] The men remained supportive of each other's work, each making a point of attending concerts given by the other.[68] Horowitz remained a champion of Rachmaninoff's solo works and his Piano Concerto No. 3, about which Rachmaninoff remarked publicly after 7 August 1942 performance at the Hollywood Bowl: "This is the way I always dreamed my concerto should be played, but I never expected to hear it that way on Earth."[68]

In 1929, conductor and music publisher Serge Koussevitzky asked Rachmaninoff if he would select pieces from his Études-Tableaux for Italian composer Ottorino Respighi to orchestrate. Rachmaninoff agreed, giving Respighi five pieces from Études-Tableaux, Op. 33 (1911) and Études-Tableaux, Op. 39 (1917) and the inspirations behind the compositions, something that he did not previously reveal. Respighi, however, titled each piece from the clues Rachmaninoff gave him and completed the orchestrations in 1930.[69] During his summers from 1929 to 1931, Rachmaninoff spent his time in Clairefontaine-en-Yvelines near Rambouillet, France, meeting with fellow Russian emigrates there.

Final compositions, illness and death

Demanding concert tour schedules caused Rachmaninoff's output as a composer to slow significantly, so that between his arrival in the US in 1918 and his death in 1943, he completed just six compositions. He kept occupied performing to support his family, but his nostalgia for Russia seemed to dampen his compositional creativity.[70] So demanding was his schedule that he termed his concert season 'harvest time’, becoming increasingly disillusioned, and entrenched in the idea of his being a failure: ‘I was born a failure and therefore I bear all the burdens that are inseparably part of this status,’ he wrote to Yevgeny Somov in 1923. Despite Rachmaninoff’s concerns, he was lauded by the American public, who loved seeing the famous composer of their favourite Prelude in C Sharp Minor. However, such popularity was not without its pressures. Whilst the American public clamoured for him, critical reception was divided and Rachmaninoff had to continually defend himself in the age-old debate of whether music could be both ‘serious’ and popular. His retort was that his music could be both:

‘I believe it is possible to be very serious, to have something to say, and at the same time be popular.’

Some asserted that Rachmaninoff's music was derivative, perhaps because he was a Romantic at heart and eschewed much of the contemporary revolution in musical thought which was emerging in the early 20th century. Music critic Paul Rosenfeld’s remark that Rachmaninoff's music ‘wants the imprint of a decided and important individuality,’ can have done nothing to alleviate the composer's writer's block.

Rachmaninoff did eventually return to composing in 1932, following the completion of his new home, Villa Senar, near Hertenstein, Lake Lucerne in Switzerland, where he retreated during his summers from 1932 to 1939. In the comfort of his own villa, which reminded him of his old family estate in Russia, Rachmaninoff composed Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini in 1934 and Symphony No. 3 (Op. 44, 1935–36).

In December 1939, Rachmaninoff conducted the Philadelphia Orchestra, his first conducting role since January 1917, his last appearance as a conductor in Russia.[71] In the early 1940s, he was approached by the makers of the British film Dangerous Moonlight to write a short concerto-like piece for use in the film, but he declined. The job went to Richard Addinsell and the orchestrator Roy Douglas, who came up with the Warsaw Concerto.[72] Rachmaninoff's last completed work, Symphonic Dances (Op. 45, 1940), was the only piece he composed in its entirety while living in the U.S. Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra premiered Symphonic Dances on 7 January 1941 at the Academy of Music.

In 1942, Rachmaninoff's doctor advised him to move to a warmer climate; his family settled in Beverly Hills, California. Later that year, Rachmaninoff fell ill during a concert tour and was later diagnosed with advanced melanoma. His family was informed, but he was not. On 1 February 1943, Rachmaninoff and Satina became American citizens.[73] His last recital, performed on 17 February 1943 at the Alumni Gymnasium at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville, Tennessee, included Chopin's Piano Sonata No. 2 which contains a funeral march. He became so ill after the performance that he had to return home.[74] Rachmaninoff died on 28 March 1943, four days before his 70th birthday. A choir sang his All Night Vigil at his funeral. He had wanted to be buried at Villa Senar, his estate in Switzerland, but the conditions of World War II made fulfilling his request impossible.[75] Instead, he was interred on 1 June in Kensico Cemetery in Valhalla, New York.[8] A statue marked "Rachmaninoff: The Last Concert", designed and sculpted by Victor Bokarev, stands at the World Fair Park in Knoxville as a tribute.

After Rachmaninoff's death, poet Marietta Shaginyan published fifteen letters they exchanged from their first contact in February 1912 and their final meeting in July 1917.[76] The nature of their relationship bordered on romantic, but was primarily intellectual and emotional. Shaginyan and the poetry she shared with Rachmaninoff has been cited as the inspiration for the six songs that make up his Six Songs, Op. 38.[77]

In August 2015, Russia announced its intentions to seek reburial of Rachmaninoff's remains in Russia, claiming that Americans have neglected the composer's grave while attempting to "shamelessly privatize" his name. The composer's descendants have resisted this idea, pointing out that he died in the U.S. after spending decades outside of Russia in self-imposed political exile.[78][79]

Works

Rachmaninoff wrote five works for piano and orchestra: four concertos—No. 1 in F-sharp minor, Op. 1 (1891, revised 1917), No. 2 in C minor, Op. 18 (1900–01), No. 3 in D minor, Op. 30 (1909), and No. 4 in G minor, Op. 40 (1926, revised 1928 and 1941)—plus the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini. Of the concertos, the Second and Third are the most popular.[80]

Rachmaninoff also composed a number of works for orchestra alone. The three symphonies: No. 1 in D minor, Op. 13 (1895), No. 2 in E minor, Op. 27 (1907), and No. 3 in A minor, Op. 44 (1935–36). Widely spaced chronologically, the symphonies represent three distinct phases in his compositional development. The Second has been the most popular of the three since its first performance. Other orchestral works include The Rock (Op. 7), Caprice bohémien (Op. 12), The Isle of the Dead (Op. 29), and the Symphonic Dances (Op. 45).

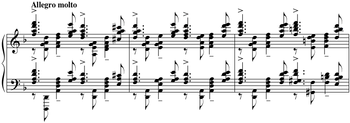

Works for piano solo include 24 Preludes traversing all 24 major and minor keys; Prelude in C-sharp minor (Op. 3, No. 2) from Morceaux de fantaisie (Op. 3); ten preludes in Op. 23; and thirteen in Op. 32. Especially difficult are the two sets of Études-Tableaux, Op. 33 and 39, which are very demanding study pictures. Stylistically, Op. 33 hearkens back to the preludes, while Op. 39 shows the influences of Scriabin and Prokofiev. There are also the Six moments musicaux (Op. 16), the Variations on a Theme of Chopin (Op. 22), and the Variations on a Theme of Corelli (Op. 42). He wrote two piano sonatas, both of which are large scale and virtuosic in their technical demands. Rachmaninoff also composed works for two pianos, four hands, including two Suites (the first subtitled Fantasie-Tableaux), a version of the Symphonic Dances (Op. 45), and an arrangement of the C-sharp minor Prelude, as well as a Russian Rhapsody, and he arranged his First Symphony (below) for piano four hands. Both these works were published posthumously.

Rachmaninoff wrote two major a cappella choral works—the Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom and the All-Night Vigil (also known as the Vespers). It was the fifth movement of All-Night Vigil that Rachmaninoff requested to have sung at his funeral. Other choral works include a choral symphony, The Bells; the cantata Spring; the Three Russian Songs; and an early Concerto for Choir (a cappella).

He completed three operas, all short: Aleko (1892), The Miserly Knight (1903), and Francesca da Rimini (1904). He started three others, notably Monna Vanna, based on a work by Maurice Maeterlinck; copyright in this had been extended to the composer Février, and, though the restriction did not pertain to Russia, Rachmaninoff dropped the project after completing Act I in piano vocal score in 1908; this act was orchestrated in 1984 by Igor Buketoff and performed in the U.S. Aleko is regularly performed and has been recorded complete at least eight times, and filmed. The Miserly Knight adheres to Pushkin's "little tragedy". Francesca da Rimini exists somewhat in the shadow of the opera of the same name by Riccardo Zandonai.

His chamber music includes two piano trios, both which are named Trio Elégiaque (the second of which is a memorial tribute to Tchaikovsky), and a Cello Sonata. He also composed many songs for voice and piano, to texts by A. N. Tolstoy, Pushkin, Goethe, Shelley, Hugo and Chekhov, among others. Among his most popular songs is the wordless Vocalise.

Compositional style

Rachmaninoff's style showed initially the influence of Tchaikovsky. Beginning in the mid-1890s, his compositions began showing a more individual tone. His First Symphony has many original features. Its brutal gestures and uncompromising power of expression were unprecedented in Russian music at the time. Its flexible rhythms, sweeping lyricism and stringent economy of thematic material were all features he kept and refined in subsequent works. After the three fallow years following the poor reception of the symphony, Rachmaninoff's style began developing significantly. He started leaning towards sumptuous harmonies and broadly lyrical, often passionate melodies. His orchestration became subtler and more varied, with textures carefully contrasted, and his writing on the whole became more concise.[81]

Especially important is Rachmaninoff's use of unusually widely spaced chords for bell-like sounds: this occurs in many pieces, most notably in the choral symphony The Bells, the Second Piano Concerto, the E flat major Étude-Tableaux (Op. 33, No. 7), and the B-minor Prelude (Op. 32, No. 10). "It is not enough to say that the church bells of Novgorod, St Petersburg and Moscow influenced Rachmaninov and feature prominently in his music. This much is self-evident. What is extraordinary is the variety of bell sounds and breadth of structural and other functions they fulfil."[82] He was also fond of Russian Orthodox chants. He uses them most perceptibly in his Vespers, but many of his melodies found their origins in these chants. The opening melody of the First Symphony is derived from chants. (The opening melody of the Third Piano Concerto, on the other hand, is not derived from chants; when asked, Rachmaninoff said that "it had written itself".)[83]

Rachmaninoff's frequently used motifs include the Dies Irae, often just the fragments of the first phrase. Rachmaninoff had great command of counterpoint and fugal writing, thanks to his studies with Taneyev. The above-mentioned occurrence of the Dies Irae in the Second Symphony (1907) is but a small example of this. Very characteristic of his writing is chromatic counterpoint. This talent was paired with a confidence in writing in both large- and small-scale forms. The Third Piano Concerto especially shows a structural ingenuity, while each of the preludes grows from a tiny melodic or rhythmic fragment into a taut, powerfully evocative miniature, crystallizing a particular mood or sentiment while employing a complexity of texture, rhythmic flexibility and a pungent chromatic harmony.[84]

His compositional style had already begun changing before the October Revolution deprived him of his homeland. The harmonic writing in The Bells was composed in 1913 but not published until 1920. This may have been due to Rachmaninoff's main publisher, Gutheil, having died in 1914 and Gutheil's catalog being acquired by Serge Koussevitsky.[85] It became as advanced as in any of the works Rachmaninoff would write in Russia, partly because the melodic material has a harmonic aspect which arises from its chromatic ornamentation.[86] Further changes are apparent in the revised First Piano Concerto, which he finished just before leaving Russia, as well as in the Op. 38 songs and Op. 39 Études-Tableaux. In both these sets Rachmaninoff was less concerned with pure melody than with coloring. His near-Impressionist style perfectly matched the texts by symbolist poets.[87] The Op. 39 Études-Tableaux are among the most demanding pieces he wrote for any medium, both technically and in the sense that the player must see beyond any technical challenges to a considerable array of emotions, then unify all these aspects[88]

The composer's friend Vladimir Wilshaw noticed this compositional change continuing in the early 1930s, with a difference between the sometimes very extroverted Op. 39 Études-Tableaux (the composer had broken a string on the piano at one performance) and the Variations on a Theme of Corelli (Op. 42, 1931). The variations show an even greater textural clarity than in the Op. 38 songs, combined with a more abrasive use of chromatic harmony and a new rhythmic incisiveness. This would be characteristic of all his later works—the Piano Concerto No. 4 (Op. 40, 1926) is composed in a more emotionally introverted style, with a greater clarity of texture. Nevertheless, some of his most beautiful (nostalgic and melancholy) melodies occur in the Third Symphony, Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, and Symphonic Dances.[87]

Fluctuating reputation

His reputation as a composer generated a variety of opinions before his music gained steady recognition across the world. The 1954 edition of the Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians notoriously dismissed Rachmaninoff's music as "monotonous in texture ... consist[ing] mainly of artificial and gushing tunes" and predicted that his popular success was "not likely to last".[89] To this, Harold C. Schonberg, in his Lives of the Great Composers, responded: "It is one of the most outrageously snobbish and even stupid statements ever to be found in a work that is supposed to be an objective reference."[89]

The Conservatoire Rachmaninoff in Paris, as well as streets in Veliky Novgorod (which is close to his birthplace) and Tambov, are named after the composer. In 1986, the Moscow Conservatory dedicated a concert hall on its premises to Rachmaninoff, designating the 252-seat auditorium Rachmaninoff Hall. A monument to Rachmaninoff was unveiled in Veliky Novgorod, near his birthplace, on 14 June 2009.

Pianism

Technique

Rachmaninoff ranked among the finest pianists of his time, along with Leopold Godowsky, Ignaz Friedman, Moriz Rosenthal, Josef Lhévinne, and Josef Hofmann, and he was famed for possessing a clean and virtuosic technique. His playing was marked by precision, rhythmic drive, notable use of staccato and the ability to maintain clarity when playing works with complex textures. Rachmaninoff applied these qualities in music by Chopin, including the B-flat minor Piano Sonata. Rachmaninoff's repertoire, excepting his own works, consisted mainly of standard 19th Century virtuoso works plus music by Bach, Beethoven, Borodin, Debussy, Grieg, Liszt, Mendelssohn, Mozart, Schubert, Schumann and Tchaikovsky.[90]

Rachmaninoff possessed extremely large hands, with which he could easily maneuver through the most complex chordal configurations. His left hand technique was unusually powerful. His playing was marked by definition—where other pianists' playing became blurry-sounding from overuse of the pedal or deficiencies in finger technique, Rachmaninoff's textures were always crystal clear. Only Josef Hofmann and Josef Lhévinne shared this kind of clarity with him.[91] All three men had Anton Rubinstein as a model for this kind of playing—Hofmann as a student of Rubinstein's,[92] Rachmaninoff from hearing his famous series of historical recitals in Moscow while studying with Zverev,[93] and Lhevinne from hearing and playing with him.

The two pieces Rachmaninoff singled out for praise from Rubinstein's concerts became cornerstones for his own recital programs. The compositions were Beethoven's Appassionata and Chopin's Funeral March Sonata. He may have based his interpretation of the Chopin sonata on Rubinstein's. Rachmaninoff biographer Barrie Martyn points out similarities between written accounts of Rubinstein's interpretation and Rachmaninoff's audio recording of the work.[94]

As part of his daily warm-up exercises, Rachmaninoff would play the technically difficult Étude in A-flat, Op. 1, No. 2, attributed to Paul de Schlözer.[95]

Tone

From those barely moving fingers came an unforced, bronzelike sonority and an accuracy bordering on infallibility.[96] Arthur Rubinstein wrote:

He had the secret of the golden, living tone which comes from the heart ... I was always under the spell of his glorious and inimitable tone which could make me forget my uneasiness about his too rapidly fleeting fingers and his exaggerated rubatos. There was always the irresistible sensuous charm, not unlike Kreisler's.[97]

Coupled to this tone was a vocal quality not unlike that attributed to Chopin's playing. With Rachmaninoff's extensive operatic experience, he was a great admirer of fine singing. As his records demonstrate, he possessed a tremendous ability to make a musical line sing, no matter how long the notes or how complex the supporting texture, with most of his interpretations taking on a narrative quality. With the stories he told at the keyboard came multiple voices—a polyphonic dialogue, not the least in terms of dynamics. His 1940 recording of his transcription of the song "Daisies" captures this quality extremely well. On the recording, separate musical strands enter as if from various human voices in eloquent conversation. This ability came from an exceptional independence of fingers and hands.[98]

Memory

Rachmaninoff also possessed an uncanny memory—one that would help put him in good stead when he had to learn the standard piano repertoire as a 45-year-old exile. He could hear a piece of music, even a symphony, then play it back the next day, the next year, or a decade after that. Siloti would give him a long and demanding piece to learn, such as Brahms' Variations and Fugue on a Theme by Handel. Two days later Rachmaninoff would play it "with complete artistic finish." Alexander Goldenweiser said, "Whatever composition was ever mentioned—piano, orchestral, operatic, or other—by a Classical or contemporary composer, if Rachmaninoff had at any time heard it, and most of all if he liked it, he played it as though it were a work he had studied thoroughly."[99]

Interpretations

Regardless of the music, Rachmaninoff always planned his performances carefully. He based his interpretations on the theory that each piece of music has a "culminating point." Regardless of where that point was or at which dynamic within that piece, the performer had to know how to approach it with absolute calculation and precision; otherwise, the whole construction of the piece could crumble and the piece could become disjointed. This was a practice he learned from Russian bass Feodor Chaliapin, a staunch friend.[90] Paradoxically, Rachmaninoff often sounded like he was improvising, though he actually was not. While his interpretations were mosaics of tiny details, when those mosaics came together in performance, they might, according to the tempo of the piece being played, fly past at great speed, giving the impression of instant thought.[100]

One advantage Rachmaninoff had in this building process over most of his contemporaries was in approaching the pieces he played from the perspective of a composer rather than that of an interpreter. He believed "interpretation demands something of the creative instinct. If you are a composer, you have an affinity with other composers. You can make contact with their imaginations, knowing something of their problems and their ideals. You can give their works color. That is the most important thing for me in my interpretations, color. So you make music live. Without color it is dead."[101] Nevertheless, Rachmaninoff also possessed a far better sense of structure than many of his contemporaries, such as Hofmann, or the majority of pianists from the previous generation, judging from their respective recordings.[98]

A recording which showcases Rachmaninoff's approach is the Liszt Second Polonaise, recorded in 1925. Percy Grainger, who had been influenced by the composer and Liszt specialist Ferruccio Busoni, had himself recorded the same piece a few years earlier. Rachmaninoff's performance is far more taut and concentrated than Grainger's. The Russian's drive and monumental conception bear a considerable difference to the Australian's more delicate perceptions. Grainger's textures are elaborate. Rachmaninoff shows the filigree as essential to the work's structure, not simply decorative.[102]

Speculations about Marfan syndrome and acromegaly

Along with his musical gifts, Rachmaninoff possessed physical gifts that may have placed him in good stead as a pianist. These gifts included exceptional height and extremely large hands with a gigantic finger stretch (he could play the chord C E♭ G C G with his left hand). This and Rachmaninoff's slender frame, long limbs, narrow head, prominent ears, and thin nose suggest that he may have had Marfan syndrome, a hereditary disorder of the connective tissue. This syndrome would have accounted for several minor ailments he suffered all his life, including back pain, arthritis, eye strain, and bruising of the fingertips,[103] although others have pointed out that this was more likely because he was playing the piano all day long. This Marfan speculation was proposed by Dr. D. A. B. Young (formerly principal scientist of the Wellcome Foundation) in a 1986 British Medical Journal article. Twenty years later, an article in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, by Ramachandran and Aronson differed greatly from Young’s speculation:

- The size of [Rachmaninov’s] hands may have been a manifestation of Marfan's syndrome, their size and slenderness typical of arachnodactyly. However, Rachmaninov did not clearly exhibit any of the other clinical characteristics typical of Marfan's, such as scoliosis, pectus excavatum, and eye or cardiac complications. Nor did he express any of the clinical effects of a Marfan-related syndrome, such as Beal's syndrome (congenital contractural arachnodactyly), Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, homocystinuria, Stickler syndrome, or Sphrintzen-Goldberg syndrome. There is no indication that his immediate family had similar hand spans, ruling out familial arachnodactyly. Rachmaninov did not display any signs of digital clubbing or any obvious hypertrophic skin changes associated with pachydermoperiostitis.

- Acromegaly is an alternative diagnosis. From photographs of Rachmaninov in the 1920s and his portrait by Konstantin Somov in 1925 (Figure 1), at a time when he was recording his four piano concerti, the coarse facial features of acromegaly are not immediately apparent. However, a case can be made from later photographs...

- During a heavy concert schedule in Russia in 1912, he interrupted his schedule because of stiffness in his hands. This may have been due to overuse, although carpal tunnel syndrome or simply swelling and puffiness of the hands associated with acromegaly may have been the cause. In 1942, Rachmaninov made a final revision of his troublesome Fourth Concerto but composed no more new music. A rapidly progressing melanoma forced him to break off his 1942–1943 concert tour after a recital in Knoxville, Tennessee. A little over five weeks later he died in the house he had bought the year before on Elm Drive in Beverly Hills. Melanoma is associated with acromegaly and may have been a final clue to Rachmaninov's diagnosis.

- But then again, perhaps he just had big hands.[104]

Contrary to rumors of "six and a half feet," Rachmaninoff’s physical height is documented in repeated (10 November 1918 and 30 October 1924) U.S. Immigration manifests at Ellis Island as 6'-1".[105] However, conductor Eugene Ormandy (who teamed with Rachmaninoff in many piano and orchestra performances) recalled in 1979: "He [Rachmaninoff] was about six feet-three. I am five feet-five and a half..."[106][107] Therefore, Rachmaninoff's height would also not be considered a physical deformity or abnormality.[108]

Recordings

Phonograph

Many of Rachmaninoff's recordings are acknowledged classics. In 1919, Rachmaninoff recorded a selection of piano pieces for Edison Records on their "Diamond Disc" records,[109] as they claimed the best audio fidelity in piano recording. Thomas Edison, who was quite deaf,[110] did not care for Rachmaninoff's playing, or for classical music in general, and referred to him as a "pounder" at their initial meeting.[111] However, staff at the Edison recording studio in New York City asked Edison to reconsider his dismissive position, resulting in a limited contract for ten released sides. Rachmaninoff recorded on a Lauter concert grand piano, one of the few the company made. He felt his performances varied in quality and requested final approval prior to a commercial release. Edison agreed, but still issued multiple takes, an unusual practice which was standard at Edison Records, where strict company policy demanded three good takes of each piece in case of damage or wear to the masters. Rachmaninoff and Edison Records were pleased with the released discs and wished to record more, but Edison refused, saying the ten sides were sufficient.

In 1920, Rachmaninoff signed a contract with the Victor Talking Machine Company (later RCA Victor). The company was pleased to comply with his requests, and proudly advertised him as one of their prominent recording artists. He continued to record for Victor until 1942, when the American Federation of Musicians imposed a recording ban on their members in a strike over royalty payments.

Particularly renowned are his renditions of Schumann's Carnaval and Chopin's Funeral March Sonata, along with many shorter pieces. He recorded all four of his piano concertos with the Philadelphia Orchestra, including two versions of the second concerto with Leopold Stokowski conducting (an acoustical recording in 1924 and a complete electrical recording in 1929), and a world premiere recording of the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, soon after the first performance (1934) with the Philadelphians under Stokowski. The first, third, and fourth concertos were recorded with Eugene Ormandy in 1939–41. Rachmaninoff also made three recordings conducting the Philadelphia Orchestra in his own Third Symphony, his symphonic poem Isle of the Dead, and his orchestration of Vocalise.[109] All of these recordings were reissued by RCA Victor in a 10-CD set "Sergei Rachmaninoff The Complete Recordings" (RCA Victor Gold Seal 09026-61265-2).

In an article for Gramophone, April 1931, Rachmaninoff defended an earlier stated view on the musical value of radio, about which he was sceptical: "the modern gramophone and modern methods of recording are musically superior to wireless transmission in every way".[112]

Piano rolls

Rachmaninoff was also involved in various ways with music on piano rolls. Several manufacturers, and in particular the Aeolian Company, had published his compositions on perforated music rolls from about 1900 onwards.[113] His sister-in-law, Sofia Satina, remembered him at the family estate at Ivanovka, pedalling gleefully through a set of rolls of his Second Piano Concerto, apparently acquired from a German source,[114] most probably the Aeolian Company's Berlin subsidiary, the Choralion Company. Aeolian in London created a set of three rolls of this concerto in 1909, which remained in the catalogues of its various successors until the late 1970s.[115]

From 1919 he made 35 piano rolls (12 of which were his own compositions), for the American Piano Company (Ampico)'s reproducing piano. According to the Ampico publicity department, he initially disbelieved that a roll of punched paper could provide an accurate record, so he was invited to listen to a proof copy of his first recording. After the performance, he was quoted as saying "Gentlemen—I, Sergei Rachmaninoff, have just heard myself play!" For demonstration purposes, he recorded the solo part of his Second Piano Concerto for Ampico, though only the second movement was used publicly and has survived. He continued to record until around 1929, though his last roll, the Chopin Scherzo in B-flat minor, was not published until October 1933.[116]

See also

Notes

- ↑ "Sergei Rachmaninoff" was the spelling he used while living in the United States from 1918 until his death. His names are also transliterated as "Sergej", "Sergeĭ", "Sergey" or "Serge"; "Vasil'evič" or "Vasil'yevich"; and "Rahmaninov", "Rachmaninov", "Raxmaninov", "Rachmaninow" and "Rakhmaninoff" (and other versions; the transliteration can vary between languages) The Library of Congress standardized the usage Sergei Rachmaninoff.[1][2]

- ↑ Russia was still using old style dates in the 19th century, rendering his birthday as 20 March 1873.

References

- ↑ Naxos.com, Retrieved 25 July 2010.

- ↑ "Name Authority File for Rachmaninoff, Sergei, 1873-1943". U.S. Library of Congress. 21 November 1980. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ↑ Norris, 707.

- 1 2 Sylvester 2014, p. 2.

- ↑ Randel, Don M. (1999). The Harvard Concise Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press (Belknap). ISBN 0-674-00978-9.

- ↑ Tiron, Radu-Tudor; Lefter, Lucian-Valeriu (2015). "Genealogic and Heraldic Notes on the Moldavian Families Settled in the East (15th – 18th Centuries)". Cercetări Istorice. Iași: Editura Palatul Culturii. 34 (1): 109–136.

- ↑ Harrison, Max: Rachmaninoff: Life, Works, Recordings Life, Works, Recordings

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Harrison

- ↑ Sylvester 2014, p. 3.

- ↑ Accardi, Julie Ciamporcero (2008). "Rach Bio". Rachmaninoff. Retrieved 13 September 2008.

- ↑ Greene 1985, p. 1004.

- 1 2 von Riesemann 1934.

- ↑ Rimsky-Korsakov 1989, pp. 94–95.

- 1 2 3 4 Bertensson & Leyda 2001, p. 46.

- ↑ Giulimondi, Gabriele (20 December 2000). "Sergei Rachmaninoff". The Internet Piano Page. Archived from the original on 12 January 2008. Retrieved 14 December 2007.

- ↑ Sylvester 2014, pp. 6–7.

- ↑ Norris, Geoffrey (1993). The Master Musicians: Rachmaninoff. New York City: Schirmer Books. ISBN 0-02-870685-4.

- ↑ "Sergei Rachmaninoff". San Francisco Symphony. 2007. Archived from the original on 13 December 2007. Retrieved 14 December 2007.

- ↑ Harrison 2006, p. 84–85.

- ↑ "RACHMANINOV: Preludes Op. 23 / Cinq morceaux de fantaisie". Naxos Records. 2008. Retrieved 15 March 2008.

- ↑ "Martin Werner Plays: Schubert – Schumann – Grieg – Chopin – Rachmaninoff – Felder". Guild Music. 31 May 2007. Retrieved 15 March 2008.

- ↑ "Sergei Rachmaninoff – Composer page". Boosey & Hawkes. 2008. Retrieved 21 March 2008.

- ↑ Threlfall 1982, p. 45.

- ↑ Bertensson & Leyda 2001, p. 61.

- ↑ Bertensson & Leyda 2001, p. 62.

- 1 2 Bertensson & Leyda 2001, p. 63.

- 1 2 Norris, 709.

- 1 2 Bertensson & Leyda 2001, p. 67.

- ↑ Bertensson & Leyda 2001, p. 69.

- ↑ Bertensson & Leyda 2001, p. 70.

- ↑ Kyui, Ts., "Tretiy russkiy simfonicheskiy kontsert," Novosti i birzhevaya gazeta (17 March 1897(o.s.)), 3.

- ↑ Harrison 2006, p. 77.

- ↑ Ossovsky Alexander Viacheslavovich (1871–1957), renowned critic and musicologist and close friend of Rachmaninoff, see external links.

- ↑ Lewis, Geraint. "Programme notes for Proms performance of Glazunov's Violin Concerto". BBC.

- ↑ Brown, David. "Liner Notes to a Deutsche Grammophon recording of Rachmaninoff's 3rd Symphony" conducted by Mikhail Pletnev

- ↑ Bertensson & Leyda 2001, p. 73.

- ↑ Bertensson & Leyda 2001, p. 74.

- ↑ Bertensson & Leyda 2001, p. 76.

- ↑ Bertensson & Leyda 2001, p. 77.

- ↑ Bertensson & Leyda 2001, p. 84, 87.

- ↑ Bertensson & Leyda 2001, p. 88.

- ↑ Bertensson & Leyda 2001, p. 89, 90.

- 1 2 Bertensson & Leyda 2001, p. 90.

- ↑ Bertensson & Leyda 2001, p. 95.

- ↑ Bertensson & Leyda 2001, p. 98.

- ↑ Bertensson & Leyda 2001, p. 97.

- ↑ "Xavier Bettel, un jeune libéral pressé". La Republicain Lorrain. 26 October 2013.

- ↑ Graaff, Laurent and Morang, Hubert (18 December 2013) Xavier Bettel "Vielleicht nicht der beliebteste Premier". Revue.lu

- ↑ Moraru, Clara Aniela Bettel Spiro-Rachmaninoff – Life is a precious gift, help people around you live the way you dream to live it yourself. women-leaders.eu

- ↑ Bertensson & Leyda 2001, p. 102.

- ↑ Harrison 2006, p. 127.

- ↑ Norris, 15:553.

- ↑ Harrison 2006, pp. 148–149.

- ↑ Harrison 2006, p. 160.

- ↑ Norris, 15:551.

- ↑ Harrison 2006, p. 162.

- 1 2 Bertensson & Leyda 2001, p. 179.

- ↑ Scott 2011, pp. 108–109.

- ↑ Scott 2011, p. 111.

- ↑ Scott 2011, p. 113.

- ↑ Scott 2011, p. 117.

- ↑ Scott 2011, p. 118.

- ↑ Scott 2011, p. 119.

- ↑ Scott 2011, p. 120.

- ↑ Scott 2011, p. 122.

- ↑ Norris, 15:554.

- 1 2 Plaskin, Glenn (1983) Horowitz—a biography. New York: William Morrow and Company. ISBN 0-688-01616-2. p. 107.

- 1 2 3 "About Wizard Horowitz, Who Will Return Soon", The Milwaukee Journal, 18 April 1943, p. 66

- ↑ Bertensson & Leyda 2001, p. 262.

- ↑ "Sergei Rachmaninoff Biography". 8notes. Retrieved 2 March 2008.

- ↑ The Royal Philharmonic Society; Retrieved 17 October 2013

- ↑ "Richard Addinsell – Films as composer". filmreference.com. Retrieved 10 October 2008.

- ↑ Cunningham 2001.

- ↑ Norris, 15:554–555.

- ↑ Norris, 713.

- ↑ Bertensson & Leyda 2001, p. 176.

- ↑ Simpson, Anne (1984). "Dear Re: A Glimpse into the Six Songs of Rachmaninoff's Opus 38". College Music Symposium. 24 (1): 97–106. JSTOR 40374219.

- ↑ Bigg, Claire (18 August 2015) Rachmaninoff Family Denounces Russian Officials' Reburial Push. Radio Free Europe

- ↑ http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/blogs-news-from-elsewhere-33986803

- ↑ Piano Concerto No. 2 has made the top 3 of Classic FM (UK)'s Hall Of Fame poll, an annual survey of classical music tastes, every year since 1996 including No. 1 in the 2011 poll. In a poll of classical music listeners announced in October 2007, the ABC in Australia found that Rachmaninoff's Second Piano Concerto came second, topped only by the "Emperor" Concerto of Beethoven. See ABC.net.au, Retrieved on 24 August 2010

- ↑ Norris, 714–715.

- ↑ Carruthers, Glen (2006). "The (re)appraisal of Rachmaninov's music: contradictions and fallacies". The Musical Times. 147: 44–50. doi:10.2307/25434403. JSTOR 25434403.

- ↑ Yasser, Joseph (1969). "The Opening Theme of Rachmaninoff's Third Piano Concerto and its Liturgical Prototype". Musical Quarterly. LV (3): 313–328. doi:10.1093/mq/LV.3.313.

- ↑ Norris, 715.

- ↑ Harrison 2006, p. 191.

- ↑ Harrison 2006, pp. 190–191.

- 1 2 Norris, 716.

- ↑ Harrison 2006, p. 207.

- 1 2 Schonberg 1998, Composers, p. 520.

- 1 2 Norris, 714.

- ↑ Schonberg 1988, Virtuosi, p. 317.

- ↑ Schonberg, Pianists, 384.

- ↑ von Riesemann 1934, p. 49–52.

- ↑ Martyn 1990, pp. 368, 403–406.

- ↑ "Jorge Bolet – Encores".

- ↑ Schonberg 1988, Virtuosi, p. 315.

- ↑ Rubinstein, 1980., 87–89, 468.

- 1 2 Harrison 2006, p. 270.

- ↑ Schonberg 1998, Composers, p, 522.

- ↑ Harrison 2006, p. 268.

- ↑ Mayne, Basil (October 1936). "Conversations with Rachmaninoff". Musical Opinion.

- ↑ Harrison 2006, p. 251.

- ↑ Young, D.A.B. (1986). "Rachmaninov and Marfan's syndrome". British Medical Journal. 293 (6562): 1624–1626. doi:10.1136/bmj.293.6562.1624. PMC 1351877

. PMID 3101945.

. PMID 3101945. - ↑ Ramachandran, Manoj; Aronson, Jeffrey K. (2006). "The diagnosis of art: Rachmaninov's hand span". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 99 (10): 529–530. doi:10.1258/jrsm.99.10.529. PMC 1592053

. PMID 17066567.

. PMID 17066567. - ↑ "SVR'S HEIGHT". Rachmaninoff.org. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- ↑ Eugene Ormandy, in a conversation with Ed Cunningham, in Philadelphia. Radio station KUSC, of the USA's National Public Radio (NPR), broadcast excerpts of this conversation in 1979.

- ↑ "SVR's Vital Statistics". Rachmaninoff.org. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- ↑ "Marfan syndrome". Rachmaninoff.org. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- 1 2 Online listing of Rachmaninoff's recording sessions (based on Martyn 1990, pp. 453–497). Retrieved 23 September 2016.

- ↑ "Thomas Edison".

When Edison was 14, he contracted scarlet fever. The effect of the fever, as well as a blow to the head by an angry train conductor, caused Edison to become completely deaf in his left ear, and 80-percent deaf in the other.

- ↑ Ziemann, George (October 2003), Thomas Edison, Intellectual Property and the Recording Industry

- ↑ Gramophone. "The most significant of modern musical inventions", Gramophone, April 1931

- ↑ "Music for the Pianola and the Aeriol Piano", The Aeolian Company, New York, July 1901.

- ↑ Harrison 2006, p. 223.

- ↑ "Catalogue of Music for the Pianola and Pianola-Piano", The Orchestrelle Company, London, June 1910, and many successive catalogues.

- ↑ Obenchain, Elaine. (1987) The Complete Catalog of Ampico Reproducing Piano Rolls (Vestal Press edition). Vestal, NY: Vestal Press. ISBN 0-911572-62-7.

Bibliography

- Bertensson, Sergei; Leyda, Jay (2001). Sergei Rachmaninoff—A Lifetime in Music (Paperback ed.). New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-21421-8.

- Cunningham, Robert E. (2001). Sergei Rachmaninoff: A Bio-bibliography. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-30907-6.

- Greene, David Mason (1985). Greene's Biographical Encyclopedia of Composers. Reproducing Piano Roll Foundation. ISBN 978-0-385-14278-6.

- Harrison, Max (2006). Rachmaninoff: Life, Works, Recordings. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-826-49312-5.

- Martyn, Barrie (1990). Rachmaninoff: Composer, Pianist, Conductor. Scolar Press. ISBN 978-0-859-67809-4.

- Norris, Geoffrey; Sadie, Stanley, eds. (1980). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. MacMillan. ISBN 0-333-23111-2.

- Norris, Geoffrey (2002). The Oxford Companion to Music. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-866212-2. OCLC 59376677.

- Rimsky-Korsakov, Nikolai (1989). My Musical Life. Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-14245-3.

- Schonberg, Harold C. (1998). The Lives of the Great Composers (3 ed.). Abacus. ISBN 978-0-349-10972-5.

- Scott, Michael (2011). Rachmaninoff. The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-7242-3.

- Sylvester, Richard D. (2014). Rachmaninoff's Complete Songs: A Companion with Texts and Translations. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-2530-1259-3.

- Threlfall, Robert; Norris, G. (1982). A Catalogue of the Compositions of Rachmaninoff. London: Scolar Press. ISBN 978-0-859-67617-5.

- Schonberg, Harold C. (1988). The Virtuosi: Classical Music's Great Performers From Paganini to Pavarotti. Vintage. ISBN 0-394-75532-4.

- von Riesemann, Oskar (1934). Rachmaninoff's Recollections, Told to Oskar von Riesemann. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-836-95232-2.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Sergei Rachmaninoff |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sergei Rachmaninoff. |

| Wikisource has the text of a 1922 Encyclopædia Britannica article about Sergei Rachmaninoff. |

- Rachmaninoff Society – Vladimir Ashkenazy President (disbanded)

- "Rachmaninov material". BBC Radio 3 archives.

- Rachmaninoff's Works for Piano and Orchestra: Analysis of Rachmaninoff's Works for Piano and Orchestra

- Sergei Rachmaninoff discography at MusicBrainz

- Complete list of Rachmaninoff's performances as a conductor at the Wayback Machine (archived 27 October 2009)

- (French) A complete and precise French site on Rachmaninoff

- Biography at allmusic.com

- Sergei Vasilievitch Rachmaninoff at Find a Grave

- Discography of Sergei Rachmaninoff on Victor Records from the Encyclopedic Discography of Victor Recordings (EDVR)

- (Russian) 2008 radio program on the composer's place in Russian history

Free scores

- Works by Sergei Rachmaninoff at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Sergei Rachmaninoff at Internet Archive

- (Italian) Free scores

- Free scores by Sergei Rachmaninoff at the International Music Score Library Project

- Free scores by Sergei Rachmaninoff in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)