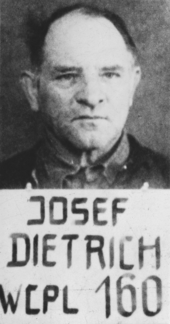

Sepp Dietrich

| Josef "Sepp" Dietrich | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

28 May 1892 Hawangen, German Empire |

| Died |

21 April 1966 (aged 73) Ludwigsburg, West Germany |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/branch |

|

| Years of service |

1911–19 1928–45 |

| Rank | Oberst-Gruppenführer |

| Service number |

NSDAP #89,015 SS #1,117 |

| Commands held |

5th Panzer Army 6th Panzer Army |

| Battles/wars |

World War II |

| Awards | Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves, Swords and Diamonds |

Josef "Sepp" Dietrich (28 May 1892 – 21 April 1966) was an Oberst-Gruppenführer in the Waffen-SS, the armed paramilitary branch of the Schutzstaffel (SS), who commanded units up to army level during World War II. Prior to 1929, he was Adolf Hitler's chauffeur and bodyguard but received rapid promotion after his participation in the extrajudicial executions of political opponents during the 1934 purge known as the Night of the Long Knives. He later commanded 6th Panzer Army during the Battle of the Bulge. After the war, he was imprisoned by the United States for war crimes and later by West Germany for his involvement in the 1934 purge.

Early life and interwar period

Sepp Dietrich was born on 28 May 1892 in Hawangen, near Memmingen in the Kingdom of Bavaria, German Empire.[1]

In 1911 he voluntarily joined the Bavarian Army with the 4. Bayerische Feldartillerie-Regiment "König" (4th Bavarian Field Artillery Regiment) in Augsburg.[2] In the First World War, he served with the Bavarian Field artillery,[2] He was promoted Gefreiter in 1917 and awarded the Iron Cross 2nd class.[3] In 1918 he was promoted Unteroffizier (sergeant).[1] Last Bavarian army record lists Dietrich as recipient of Iron Cross 1st class[3] and Bavarian Military Merit Order 3rd class with swords.

Interwar period

In the Weimar Republic

After the Great War, Dietrich worked at several jobs, including being a policeman and customs officer.[2][1] He joined the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in 1928, got a job at Eher Verlag, the NSDAP publisher, and became commander of Hitler's Schutzstaffel (SS) bodyguard.[4] His NSDAP number was 89,015 and his SS number was 1,117.[5] Dietrich had been introduced to Nazism by Christian Weber, who was his employer at the Tankstelle-Blau-Bock filling station in Munich.[6] He accompanied Hitler on his tours around Germany.[1] Later Hitler arranged other jobs, including various SS posts, and let him live in the Reich Chancellery. On 5 January 1930, Dietrich was elected to the Reichstag as a delegate for Lower Bavaria.[2]

By 1931, he had become SS-Gruppenführer.[1] When the Nazi Party seized power in 1933, Dietrich rose swiftly through the hierarchy.[1] He became the commander of Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler (LSSAH) and member of the Prussian state council.[1] As one of Hitler's intimates, Dietrich was often able to disregard his SS superior, Heinrich Himmler, at one time even banning Himmler from the Leibstandarte barracks. The LSSAH eventually grew into an elite division of the Waffen-SS. Although nominally under Himmler, Dietrich was the real commander and handled day-to-day administration.[7]

In summer 1934, Dietrich played a key role in the Night of the Long Knives. Hitler along with Dietrich and a unit from the Leibstandarte travelled to Bad Wiessee to personally oversee Röhm's arrest on 30 June. Later at around 17:00 hours, Dietrich received orders from Hitler for the Leibstandarte to form an "execution squad" and go to Stadelheim prison where certain SA leaders were being held.[8] There in the prison courtyard, the Leibstandarte firing squad shot five SA generals and a SA colonel.[9] Additional alleged "traitors" were shot in Berlin by a unit of the Leibstandarte after Hitler told him to take six men and go to the Ministry of Justice to shoot certain Sturmabteilung (SA) leaders.[1][10] Shortly thereafter, he was promoted to SS-Obergruppenführer.[2] Dietrich's role later earned him a nineteen-month sentence from a postwar court.[1]

World War II

_Dietrich.jpg)

After World War II began, Dietrich led the Leibstandarte during the German advance into Poland and later the Netherlands. After the Dutch surrender, the Leibstandarte moved south to France on 24 May 1940. They took up a position 15 miles south west of Dunkirk along the line of the Aa Canal, facing the Allied defensive line near Watten.[11] That night the OKW ordered the advance to halt, with the British Expeditionary Force trapped. The Leibstandarte paused for the night. However, on the following day, in defiance of Hitler's orders, Dietrich ordered his III Battalion to cross the canal and take the heights beyond, where British artillery observers were putting the regiment at risk. They assaulted the heights and drove the observers off. Instead of being censured for his act of defiance, Dietrich was awarded the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross.[12]

Dietrich remained in command of the Leibstandarte throughout the campaigns in Greece and Yugoslavia before being promoted to command of the 1st SS Panzer Corps, attached to Army Group Center, on the Eastern Front. In 1943, he was sent to Italy to recover Benito Mussolini's mistress Clara Petacci.[1] He received numerous German military medals.[3]

Dietrich commanded the 1st SS Panzer Corps in the Battle of Normandy. He rose to command 5th Panzer Army during the later stages of this campaign. Hitler gave him the command of the newly created 6th Panzer Army. Dietrich commanded it in the Battle of the Bulge (December 1944 – January 1945).[1] He had been assigned to that task because, due to the 20 July Plot, Hitler distrusted Wehrmacht officers. On 17 December, Kampfgruppe Peiper, (an SS unit) under his overall command killed 84 U.S. prisoners of war near Malmedy, Belgium, in what is known as the Malmedy massacre.[1] Interestingly, Dietrich was already becoming disillusioned with Hitler's war leadership and is said to have told Field Marshal Erwin Rommel that if he sought a separate peace on the Western Front, he (Dietrich) would support him.[Note 1]

In March 1945, Dietrich's 6th Panzer Army and the LSSAH spearheaded Operation Spring Awakening, an offensive in Hungary near Lake Balaton aimed at securing the last oil reserves still available to Germany. Despite early gains, the offensive was too ambitious in scope and failed.[14] After the failure of the operation the 6th SS Panzer Army (and LSSAH) retreated to the Vienna area.[15] As a mark of disgrace, the Waffen-SS units involved in the battle were ordered by Hitler to remove their treasured cuff titles. Dietrich did not relay the order to his troops.[14] Shortly thereafter, Dietrich's troops were forced to retreat from Vienna by the Soviet Red Army forces.[16] Dietrich, accompanied by his wife, surrendered on 9 May 1945 to the U.S. 36th Infantry Division in Austria.

Assessment

Dietrich had complete confidence of the Führer because of his plain-speaking loyalty; the old political fighter was one of Hitler's favorites. He therefore enjoyed much lavish publicity, numerous decorations and rapid series of promotions. Dietrich often took gambles, much to the dislike of the OKW, such as when he sent the Leibstandarte division 'charging into Rostov' without orders 'purely to gain a prestige victory'. Once Dietrich was promoted to a Corps command he was at least assisted by competent staff officers transferred from the army; still the army command had to take some pains to keep him in line.[17]

By 1944 there were clear signs that he had been elevated above his military competence. He reportedly had never been taught how to read a military map. Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt considered him to be 'decent but stupid' and was especially critical of Dietrich's handling of the 6th Panzer Army in the Ardennes. Even Dietrich's principal staff officer conceded that he was 'no strategic genius'.[17]

Dietrich's long, personal acquaintance with Hitler allowed him to be more frank than other senior officers in his interactions with Hitler. He was reported by a fellow general to have 'railed against the Führer and [his] entourage' with promises to let Hitler know that he was 'leading us all to destruction'.[Note 2]

War crimes conviction

Dietrich was tried as Defendant No. 11 by U.S. Military Tribunal at Dachau ("United States of America vs. Valentin Bersin et al.", Case No. 6-24), from 16 May 1946 until 16 July 1946. On 16 July 1946, he was sentenced to life imprisonment in the Malmedy massacre trial for his involvement in ordering the execution of U.S. prisoners of war.[2] Due to testimony in his defence by other German officers, his sentence was shortened to 25 years. He was imprisoned at the U.S. War Criminals Prison No. 1 at Landsberg am Lech in Bavaria. Dietrich served only ten years and was released on parole on 22 October 1955.[2]

Dietrich was rearrested in Ludwigsburg in August 1956. He was charged by the Landgericht München I and tried from 6 May 1957 until 14 May 1957 for his role in the killing of SA leaders during the Night of the Long Knives in 1934.[2] On 14 May 1957, he was sentenced to nineteen months for his part in that purge and returned to the U.S. military prison at Landsberg.[1] He was released due to a heart condition and circulation problems in his legs on 2 February 1958. By then he had already served almost his entire 19-month sentence.[1]

Later life

Upon his release from prison, he took an active part in the activities of HIAG, a revisionist organization and a lobby group of former Waffen-SS members. Founded by former high-ranking Waffen-SS personnel, it campaigned for the legal, economic and historical rehabilitation of the Waffen-SS, with limited success.[19][20] In 1966, Dietrich died of a heart attack. Six thousand people attended his funeral.[21] Dietrich was married twice: he was divorced from his first wife in 1937 and remarried in 1942. He had three children.

Summary of SS career

Decorations

- Iron Cross (1914), Second (1917) and First (1918) Classes[3]

- Bavarian Military Merit Order 3rd class with swords (1918)

- Tank Memorial Badge (1921)

- Clasp to the Iron Cross (1939) 2nd Class (25 September 1939) & 1st Class (27 October 1939)[22]

- Blood Order-(Nr. 10) (1933)[3]

- Golden Party Badge (1933)[3]

- Honour Chevron for the Old Guard

- Pilot/Observer Badge in Gold with Diamonds (1943)[3]

- Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves, Swords and Diamonds

- Knight's Cross on 4 July 1940 as SS-Obergruppenführer and commander of SS Infantry Regiment "Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler"[23]

- 41st Oak Leaves on 31 December 1941 as SS-Obergruppenführer and commander of SS Division Leibstandarte [23]

- 26th Swords on 14 March 1943 as SS-Obergruppenführer and general of the Waffen-SS and commander of SS Division Leibstandarte[23]

- 16th Diamonds on 6 August 1944 as SS-Oberstgruppenführer and commander of I SS Panzer Corps[23]

Promotions

| 1 June 1928: | SS-Sturmführer[24] |

| 1 August 1928: | SS-Sturmbannführer[24] |

| 1 August 1929: | SS-Standartenführer[24] |

| 18 September 1929: | SS-Oberführer[24] |

| 11 July 1930: | SS-Brigadeführer[25] |

| 18 December 1931: | SS-Gruppenführer[25] |

| 4 July 1934: | SS-Obergruppenführer[25] |

| 1 October 1941: | General der Waffen-SS (appointed)[25] |

| 20 April 1942: | SS-Obergruppenführer and Panzer-General der Waffen-SS[25] |

| 1 August 1944: | SS-Oberst-Gruppenführer und Panzer-Generaloberst der Waffen-SS[25] |

Notes

- ↑ Dietrich is alleged to have said to Erwin Rommel, "You are my superior officer, and therefore I will obey all your order".[13]

- ↑ "Sepp Dietrich railed against the Führer and [the Führer's] entourage to such an extent that it became most unpleasant. Then, he was sent for, and he said: 'All right, that's fine but I shall speak my mind. I shall tell Adi' -he always calls Hitler 'Adi'- 'that he is leading us all to destruction'." Spoken by General der Panzertruppe Heinrich Eberbach while in captivity in Britain and secretly taped by the MI-19 Directorate of the British Military Intelligence.[18]

References

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Snyder 1994, p. 66.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Zentner & Bedurftig 1997, p. 197.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Ailsby 1997, p. 33.

- ↑ Cachay, Bahlke & Mehl 2000, p. 350.

- ↑ Biondi 2000, p. 7.

- ↑ Messenger 2005, p. 39.

- ↑ Cook & Bender 1994, pp. 19, 33.

- ↑ Cook & Bender 1994, pp. 22, 23.

- ↑ Cook & Bender 1994, p. 23.

- ↑ Cook & Bender 1994, p. 24.

- ↑ Flaherty 2004, p. 154.

- ↑ Flaherty 2004, pp. 143, 154.

- ↑ Meyer 1987, pp. 465–500.

- 1 2 Stein 1984, p. 238.

- ↑ Dollinger 1967, p. 198.

- ↑ Stein 1984, p. 239.

- 1 2 MacKenzie 1997, pp. 155-156.

- ↑ Neitzel 2007, p. 266.

- ↑ Caddick-Adams 2014, p. 753.

- ↑ Large 1987.

- ↑ Parker 2014, p. 216.

- ↑ Thomas 1997, p. 120.

- 1 2 3 4 Scherzer 2007, p. 272.

- 1 2 3 4 Thomas & Wegmann 1998, p. 278.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Thomas & Wegmann 1998, p. 279.

Bibliography

In English

- Ailsby, Christopher (1997). SS: Roll of Infamy. Motorbooks Intl. ISBN 0-7603-0409-2.

- Biondi, Robert (2000). SS Officers list : (as of 30 January 1942) : SS-Standartenfuhrer to SS-Oberstgruppenfuhrer : Assignments and Decorations of the Senior SS Officer Corps. Schiffer Military History Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7643-1061-4.

- Caddick-Adams, Peter (2014). Snow and Steel: The Battle of the Bulge, 1944–45. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-933514-5.

- Cook, Stan; Bender, Roger James (1994). Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler: Uniforms, Organization, & History. San Jose, CA: R. James Bender. ISBN 978-0-912138-55-8.

- Dollinger, Hans (1967) [1965]. The Decline and Fall of Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan. New York: Bonanza. ISBN 978-0-517-01313-7.

- Flaherty, T. H. (2004) [1988]. The Third Reich: The SS. Time-Life. ISBN 1-84447-073-3.

- Large, David C. (1987). "Reckoning without the Past: The HIAG of the Waffen-SS and the Politics of Rehabilitation in the Bonn Republic, 1950–1961". The Journal of Modern History. University of Chicago Press. 59 (1): 79–113. doi:10.1086/243161. JSTOR 1880378.

- MacKenzie, S.P. (1997). Revolutionary Armies in the Modern Era: A Revisionist Approach. New York: Routledge. ISBN 9780415096904.

- Messenger, Charles (2005). Hitler's Gladiator: The Life and Wars of Panzer Army Commander Sepp Dietrich. London. ISBN 978-1-84486-022-7.

- Messenger, Charles (1988). Hitler's Gladiator: The Life and Times of Oberstgruppenfuhrer and Panzergeneral-Oberst Der Waffen-SS Sepp Dietrich, London. ASIN: B000OFQ62W.

- Neitzel, Sönke (2007). Tapping Hitler's Generals: Transcripts of Secret Conversations, 1942–45. Frontline Books. ISBN 978-1-84415-705-1.

- Parker, Danny S. (2014). Hitler's Warrior: The Life and Wars of SS Colonel Jochen Peiper. Boston: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-82154-7.

- Snyder, Louis (1994) [1976]. Encyclopedia of the Third Reich. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-1-56924-917-8.

- Stein, George H. (1984). The Waffen SS: Hitler's Elite Guard at War, 1939–1945. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-9275-0.

- Zentner, Christian; Bedurftig, Friedemann (1997) [1991]. The Encyclopedia of The Third Reich. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-3068079-3-0.

In German

- Cachay, Klaus; Bahlke, Steffen; Mehl, Helmut (2000). Echte Sportler – gute Soldaten. Die Sportsozialisation des Nationalsozialismus im Spiegel von Feldpostbriefen (in German). Weinheim, München Germany: Beltz Juventa. ISBN 978-3-7799-1130-2.

- Höhne, Heinz. Der Orden unter dem Totenkopf, Verlag Der Spiegel, Hamburg 1966; English translation by Richard Barry entitled The Order of the Death's Head, The Story of Hitler's SS, London: Pan Books (1969). ISBN 0-330-02963-0.

- Meyer, Georg (1987). "Auswirkungen des 20. Juli 1944 auf das innere Gefüge der Wehrmacht bis Kriegsend und auf das soldatische Selbstverständnis im Vorfeld des westdeutschen Verteidigungsbeitrages bis 1950/51" [Effects of 20 July 1944 on the internal structure of the Armed Forces to end the war and the soldier's self-understanding in advance of the West German defense contribution to 1950/51]. Aufstand des Gewissens. Der militärische Widerstand gegen Hitler und das NS-Regime 1933–45 [Revolt of conscience. The military resistance against Hitler and the Nazi regime from 1933 to 1945] (in German) (3rd ed.). Herford, Germany: E.S. Mittler. ISBN 978-3-8132-0197-0.

- Scherzer, Veit (2007). Die Ritterkreuzträger 1939–1945 Die Inhaber des Ritterkreuzes des Eisernen Kreuzes 1939 von Heer, Luftwaffe, Kriegsmarine, Waffen-SS, Volkssturm sowie mit Deutschland verbündeter Streitkräfte nach den Unterlagen des Bundesarchives [The Knight's Cross Bearers 1939–1945 The Holders of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross 1939 by Army, Air Force, Navy, Waffen-SS, Volkssturm and Allied Forces with Germany According to the Documents of the Federal Archives] (in German). Jena, Germany: Scherzers Miltaer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-938845-17-2.

- Thomas, Franz (1997). Die Eichenlaubträger 1939–1945 Band 1: A–K [The Oak Leaves Bearers 1939–1945 Volume 1: A–K] (in German). Osnabrück, Germany: Biblio-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7648-2299-6.

- Thomas, Franz; Wegmann, Günter (1998). Die Ritterkreuzträger der Deutschen Wehrmacht 1939–1945 Teil III: Infanterie Band 4: C–Dow [The Knight's Cross Bearers of the German Wehrmacht 1939–1945 Part III: Infantry Volume 4: C–Dow] (in German). Osnabrück, Germany: Biblio-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7648-2534-8.

| Military offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by none |

Commander of Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler 17 March 1933 – 7 April 1943 |

Succeeded by SS-Brigadeführer Theodor Wisch |

| Preceded by none |

Commander of I SS Panzer Corps 4 July 1943 – 9 August 1944 |

Succeeded by SS-Brigadeführer Fritz Kraemer |

| Preceded by General of Panzer Troops Heinrich Eberbach |

Commander of 5. Panzerarmee 9 August 1944 – 9 September 1944 |

Succeeded by General of Panzer Troops Hasso von Manteuffel |

| Preceded by none |

Commander of 6. SS-Panzerarmee 26 October 1944 – 8 May 1945 |

Succeeded by dissolved on 8 May 1945 |