Scale-free network

| Network science | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Network types | ||||

| Graphs | ||||

|

||||

| Models | ||||

|

||||

| ||||

|

||||

A scale-free network is a network whose degree distribution follows a power law, at least asymptotically. That is, the fraction P(k) of nodes in the network having k connections to other nodes goes for large values of k as

where is a parameter whose value is typically in the range 2 < < 3, although occasionally it may lie outside these bounds.[1][2]

Many networks have been reported to be scale-free, although statistical analysis has refuted many of these claims and seriously questioned others.[3] Preferential attachment and the fitness model have been proposed as mechanisms to explain conjectured power law degree distributions in real networks.

History

In studies of the networks of citations between scientific papers, Derek de Solla Price showed in 1965 that the number of links to papers—i.e., the number of citations they receive—had a heavy-tailed distribution following a Pareto distribution or power law, and thus that the citation network is scale-free. He did not however use the term "scale-free network", which was not coined until some decades later. In a later paper in 1976, Price also proposed a mechanism to explain the occurrence of power laws in citation networks, which he called "cumulative advantage" but which is today more commonly known under the name preferential attachment.

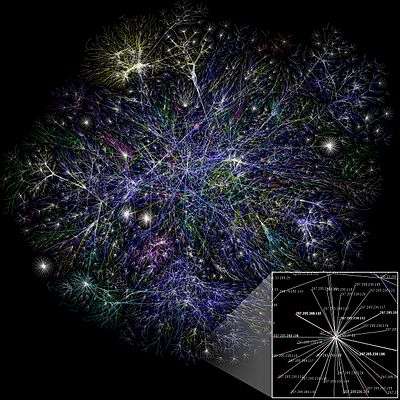

Recent interest in scale-free networks started in 1999 with work by Albert-László Barabási and colleagues at the University of Notre Dame who mapped the topology of a portion of the World Wide Web,[4] finding that some nodes, which they called "hubs", had many more connections than others and that the network as a whole had a power-law distribution of the number of links connecting to a node. After finding that a few other networks, including some social and biological networks, also had heavy-tailed degree distributions, Barabási and collaborators coined the term "scale-free network" to describe the class of networks that exhibit a power-law degree distribution. Amaral et al. showed that most of the real-world networks can be classified into two large categories according to the decay of degree distribution P(k) for large k.

Barabási and Albert proposed a generative mechanism to explain the appearance of power-law distributions, which they called "preferential attachment" and which is essentially the same as that proposed by Price. Analytic solutions for this mechanism (also similar to the solution of Price) were presented in 2000 by Dorogovtsev, Mendes and Samukhin [5] and independently by Krapivsky, Redner, and Leyvraz, and later rigorously proved by mathematician Béla Bollobás.[6] Notably, however, this mechanism only produces a specific subset of networks in the scale-free class, and many alternative mechanisms have been discovered since.[7]

The history of scale-free networks also includes some disagreement. On an empirical level, the scale-free nature of several networks has been called into question. For instance, the three brothers Faloutsos believed that the Internet had a power law degree distribution on the basis of traceroute data; however, it has been suggested that this is a layer 3 illusion created by routers, which appear as high-degree nodes while concealing the internal layer 2 structure of the ASes they interconnect. [8] On a theoretical level, refinements to the abstract definition of scale-free have been proposed. For example, Li et al. (2005) recently offered a potentially more precise "scale-free metric". Briefly, let G be a graph with edge set E, and denote the degree of a vertex (that is, the number of edges incident to ) by . Define

This is maximized when high-degree nodes are connected to other high-degree nodes. Now define

where smax is the maximum value of s(H) for H in the set of all graphs with degree distribution identical to that of G. This gives a metric between 0 and 1, where a graph G with small S(G) is "scale-rich", and a graph G with S(G) close to 1 is "scale-free". This definition captures the notion of self-similarity implied in the name "scale-free".

Characteristics

The most notable characteristic in a scale-free network is the relative commonness of vertices with a degree that greatly exceeds the average. The highest-degree nodes are often called "hubs", and are thought to serve specific purposes in their networks, although this depends greatly on the domain.

The scale-free property strongly correlates with the network's robustness to failure. It turns out that the major hubs are closely followed by smaller ones. These smaller hubs, in turn, are followed by other nodes with an even smaller degree and so on. This hierarchy allows for a fault tolerant behavior. If failures occur at random and the vast majority of nodes are those with small degree, the likelihood that a hub would be affected is almost negligible. Even if a hub-failure occurs, the network will generally not lose its connectedness, due to the remaining hubs. On the other hand, if we choose a few major hubs and take them out of the network, the network is turned into a set of rather isolated graphs. Thus, hubs are both a strength and a weakness of scale-free networks. These properties have been studied analytically using percolation theory by Cohen et al.[9][10] and by Callaway et al.[11] It was proven by Cohen [12] that for a broad range of scale free networks the critical percolation threshold, p_c=0. This means the removing randomly any fraction of nodes from scale network will not destroy the network. This is in contrast to Erdős–Rényi graph where p_c =1/<k>, where <k> is the average degree.

Another important characteristic of scale-free networks is the clustering coefficient distribution, which decreases as the node degree increases. This distribution also follows a power law. This implies that the low-degree nodes belong to very dense sub-graphs and those sub-graphs are connected to each other through hubs. Consider a social network in which nodes are people and links are acquaintance relationships between people. It is easy to see that people tend to form communities, i.e., small groups in which everyone knows everyone (one can think of such community as a complete graph). In addition, the members of a community also have a few acquaintance relationships to people outside that community. Some people, however, are connected to a large number of communities (e.g., celebrities, politicians). Those people may be considered the hubs responsible for the small-world phenomenon.

At present, the more specific characteristics of scale-free networks vary with the generative mechanism used to create them. For instance, networks generated by preferential attachment typically place the high-degree vertices in the middle of the network, connecting them together to form a core, with progressively lower-degree nodes making up the regions between the core and the periphery. The random removal of even a large fraction of vertices impacts the overall connectedness of the network very little, suggesting that such topologies could be useful for security, while targeted attacks destroys the connectedness very quickly. Other scale-free networks, which place the high-degree vertices at the periphery, do not exhibit these properties. Similarly, the clustering coefficient of scale-free networks can vary significantly depending on other topological details.

A final characteristic concerns the average distance between two vertices in a network. As with most disordered networks, such as the small world network model, this distance is very small relative to a highly ordered network such as a lattice graph. Notably, an uncorrelated power-law graph having 2 < γ < 3 will have ultrasmall diameter d ~ ln ln N where N is the number of nodes in the network, as proved by Cohen and Havlin.[13] The diameter of a growing scale-free network might be considered almost constant in practice.

Examples

Although many real-world networks are thought to be scale-free, the evidence often remains inconclusive, primarily due to the developing awareness of more rigorous data analysis techniques.[3] As such, the scale-free nature of many networks is still being debated by the scientific community. A few examples of networks claimed to be scale-free include:

- Social networks, including collaboration networks. Two examples that have been studied extensively are the collaboration of movie actors in films and the co-authorship by mathematicians of papers.

- Many kinds of computer networks, including the internet and the webgraph of the World Wide Web.

- Some financial networks such as interbank payment networks [14][15]

- Protein-protein interaction networks.

- Semantic networks.[16]

- Airline networks.

Scale free topology has been also found in high temperature superconductors.[17] The qualities of a high-temperature superconductor — a compound in which electrons obey the laws of quantum physics, and flow in perfect synchrony, without friction — appear linked to the fractal arrangements of seemingly random oxygen atoms and lattice distortion.[18]

Generative models

These scale-free networks do not arise by chance alone. Erdős and Rényi (1960) studied a model of growth for graphs in which, at each step, two nodes are chosen uniformly at random and a link is inserted between them. The properties of these random graphs are different from the properties found in scale-free networks, and therefore a model for this growth process is needed.

The most widely known generative model for a subset of scale-free networks is Barabási and Albert's (1999) rich get richer generative model in which each new Web page creates links to existing Web pages with a probability distribution which is not uniform, but proportional to the current in-degree of Web pages. This model was originally discovered by Derek J. de Solla Price in 1965 under the term cumulative advantage, but did not reach popularity until Barabási rediscovered the results under its current name (BA Model). According to this process, a page with many in-links will attract more in-links than a regular page. This generates a power-law but the resulting graph differs from the actual Web graph in other properties such as the presence of small tightly connected communities. More general models and networks characteristics have been proposed and studied (for a review see the book by Dorogovtsev and Mendes).

A somewhat different generative model for Web links has been suggested by Pennock et al. (2002). They examined communities with interests in a specific topic such as the home pages of universities, public companies, newspapers or scientists, and discarded the major hubs of the Web. In this case, the distribution of links was no longer a power law but resembled a normal distribution. Based on these observations, the authors proposed a generative model that mixes preferential attachment with a baseline probability of gaining a link.

Another generative model is the copy model studied by Kumar et al.[19] (2000), in which new nodes choose an existent node at random and copy a fraction of the links of the existent node. This also generates a power law.

Interestingly, the growth of the networks (adding new nodes) is not a necessary condition for creating a scale-free network. Dangalchev[20] (2004) gives examples of generating static scale-free networks. Another possibility (Caldarelli et al. 2002) is to consider the structure as static and draw a link between vertices according to a particular property of the two vertices involved. Once specified the statistical distribution for these vertices properties (fitnesses), it turns out that in some circumstances also static networks develop scale-free properties.

Kasthurirathna and Piraveenan [21] have shown that in socio-ecological systems, the drive towards improved rationality on average might be an evolutionary reason for the emergence of scale-free properties. They did this by simulating a number of strategic games on an initially random network with distributed bounded rationality, then re-wiring the network so that the network on average converged towards Nash equilibria, despite the bounded rationality of nodes. They observed that this re-wiring process results in scale-free networks.

Generalized scale-free model

There has been a burst of activity in the modeling of scale-free complex networks. The recipe of Barabási and Albert[22] has been followed by several variations and generalizations[23][24][25][26] and the revamping of previous mathematical works.[27] As long as there is a power law distribution in a model, it is a scale-free network, and a model of that network is a scale-free model.

Features

Many real networks are (approximately) scale-free and hence require scale-free models to describe them. In Price's scheme, there are two ingredients needed to build up a scale-free model:

1. Adding or removing nodes. Usually we concentrate on growing the network, i.e. adding nodes.

2. Preferential attachment: The probability that new nodes will be connected to the "old" node.

Note that Fitness models (see below) could work also statically, without changing the number of nodes. It should also be kept in mind that the fact that "preferential attachment" models give rise to scale-free networks does not "prove" that this is "the" mechanism underlying the evolution of real world-scale free networks and there might actually exist mechanisms which are at work in real world systems which nevertheless give rise to scaling.

Examples

There have been several attempts to generate scale-free network properties. Here are some examples:

The Barabási–Albert model

For example, the first scale-free model, the Barabási–Albert model, has a linear preferential attachment and adds one new node at every time step.

(Note, another general feature of in real networks is that , i.e. there is a nonzero probability that a new node attaches to an isolated node. Thus in general has the form , where is the initial attractiveness of the node.)

Two-level network model

Dangalchev[20] builds a 2-L model by adding a second-order preferential attachment. The attractiveness of a node in the 2-L model depends not only on the number of nodes linked to it but also on the number of links in each of these nodes.

where C is a coefficient between 0 and 1.

Mediation-driven attachment (MDA) model

In the mediation-driven attachment (MDA) model in which a new node coming with edges picks an existing connected node at random and then connects itself not with that one but with of its neighbors chosen also at random. The probability that the node of the existing node picked is

The factor is the inverse of the harmonic mean (IHM) of degrees of the neighbors of a node . Extensive numerical investigation suggest that for a approximately the mean IHM value in the large limit becomes a constant which means . It implies that the higher the links (degree) a node has, the higher its chance of gaining more links since they can be reached in a larger number of ways through mediators which essentially embodies the intuitive idea of rich get richer mechanism (or the preferential attachment rule of the Barabasi–Albert model). Therefore, the MDA network can be seen to follow the PA rule but in disguise.[28]

However, for it describes the winner takes it all mechanism as we find that almost of the total nodes has degree one and one is super-rich in degree. As value increases the disparity between the super rich and poor decreases and as we find a transition from rich get super richer to rich get richer mechanism.

Non-linear preferential attachment

The Barabási–Albert model assumes that the probability that a node attaches to node is proportional to the degree of node . This assumption involves two hypotheses: first, that depends on , in contrast to random graphs in which , and second, that the functional form of is linear in . The precise form of is not necessarily linear, and recent studies have demonstrated that the degree distribution depends strongly on

Krapivsky, Redner, and Leyvraz[25] demonstrate that the scale-free nature of the network is destroyed for nonlinear preferential attachment. The only case in which the topology of the network is scale free is that in which the preferential attachment is asymptotically linear, i.e. as . In this case the rate equation leads to

This way the exponent of the degree distribution can be tuned to any value between 2 and .

Hierarchical network model

There is another kind of scale-free model, which grows according to some patterns, such as the hierarchical network model.[29]

The iterative construction leading to a hierarchical network. Starting from a fully connected cluster of five nodes, we create four identical replicas connecting the peripheral nodes of each cluster to the central node of the original cluster. From this, we get a network of 25 nodes (N = 25). Repeating the same process, we can create four more replicas of the original cluster – the four peripheral nodes of each one connect to the central node of the nodes created in the first step. This gives N = 125, and the process can continue indefinitely.

Fitness model

The idea is that the link between two vertices is assigned not randomly with a probability p equal for all the couple of vertices. Rather, for every vertex j there is an intrinsic fitness xj and a link between vertex i and j is created with a probability .[30] Note that the model is both

In the case of World Trade Web it is possible to reconstruct all the properties by using as fitnesses of the country their GDP, and taking

Hyperbolic geometric graphs

Assuming that a network has an underlying hyperbolic geometry, one can use the framework of spatial networks to generate scale-free degree distributions. This heterogeneous degree distribution then simply reflects the negative curvature and metric properties of the underlying hyperbolic geometry.[32]

Scale-free ideal network

In the context of network theory a scale-free ideal network is a random network with a degree distribution following the scale-free ideal gas density distribution. These networks are able to reproduce city-size distributions and electoral results by unraveling the size distribution of social groups with information theory on complex networks when a competitive cluster growth process is applied to the network.[33][34] In models of scale-free ideal networks it is possible to demonstrate that Dunbar's number is the cause of the phenomenon known as the 'six degrees of separation' .

See also

- Random graph

- Erdős–Rényi model

- Non-linear preferential attachment

- Bose–Einstein condensation: a network theory approach

- Scale invariance

- Complex network

- Webgraph

- Barabási–Albert model

- Bianconi–Barabási model

References

- ↑ Onnela, J. -P.; Saramaki, J.; Hyvonen, J.; Szabo, G.; Lazer, D.; Kaski, K.; Kertesz, J.; Barabasi, A. -L. (2007). "Structure and tie strengths in mobile communication networks". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 104 (18): 7332–7336. arXiv:physics/0610104

. Bibcode:2007PNAS..104.7332O. doi:10.1073/pnas.0610245104. PMC 1863470

. Bibcode:2007PNAS..104.7332O. doi:10.1073/pnas.0610245104. PMC 1863470 . PMID 17456605.

. PMID 17456605. - ↑ Choromański, K.; Matuszak, M.; MiȩKisz, J. (2013). "Scale-Free Graph with Preferential Attachment and Evolving Internal Vertex Structure". Journal of Statistical Physics. 151 (6): 1175. Bibcode:2013JSP...151.1175C. doi:10.1007/s10955-013-0749-1.

- 1 2 Clauset, Aaron; Cosma Rohilla Shalizi; M. E. J Newman (2007-06-07). "Power-law distributions in empirical data". SIAM Review. arXiv:0706.1062

. Bibcode:2009SIAMR..51..661C. doi:10.1137/070710111.

. Bibcode:2009SIAMR..51..661C. doi:10.1137/070710111. - ↑ Barabási, Albert-László; Albert, Réka. (October 15, 1999). "Emergence of scaling in random networks". Science. 286 (5439): 509–512. arXiv:cond-mat/9910332

. Bibcode:1999Sci...286..509B. doi:10.1126/science.286.5439.509. MR 2091634. PMID 10521342.

. Bibcode:1999Sci...286..509B. doi:10.1126/science.286.5439.509. MR 2091634. PMID 10521342. - ↑ Dorogovtsev, S.; Mendes, J.; Samukhin, A. (2000). "Structure of Growing Networks with Preferential Linking". Physical Review Letters. 85 (21): 4633–4636. arXiv:cond-mat/0004434

. Bibcode:2000PhRvL..85.4633D. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.4633. PMID 11082614.

. Bibcode:2000PhRvL..85.4633D. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.4633. PMID 11082614. - ↑ Bollobás, B.; Riordan, O.; Spencer, J.; Tusnády, G. (2001). "The degree sequence of a scale-free random graph process". Random Structures and Algorithms. 18 (3): 279–290. doi:10.1002/rsa.1009. MR 1824277.

- ↑ Dorogovtsev, S. N.; Mendes, J. F. F. (2002). "Evolution of networks". Advances in Physics. 51 (4): 1079. doi:10.1080/00018730110112519.

- ↑ Willinger, Walter; David Alderson; John C. Doyle (May 2009). "Mathematics and the Internet: A Source of Enormous Confusion and Great Potential" (PDF). Notices of the AMS. American Mathematical Society. 56 (5): 586–599. Retrieved 2011-02-03.

- ↑ Cohen, Reoven; Erez, K.; ben-Avraham, D.; Havlin, S. (2000). "Resilience of the Internet to Random Breakdowns". Physical Review Letters. 85: 4626–8. arXiv:cond-mat/0007048

. Bibcode:2000PhRvL..85.4626C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.4626.

. Bibcode:2000PhRvL..85.4626C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.4626. - ↑ Cohen, Reoven; Erez, K.; ben-Avraham, D.; Havlin, S. (2001). "Breakdown of the Internet under Intentional Attack". Physical Review Letters. 86: 3682–5. arXiv:cond-mat/0010251

. Bibcode:2001PhRvL..86.3682C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.86.3682. PMID 11328053.

. Bibcode:2001PhRvL..86.3682C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.86.3682. PMID 11328053. - ↑ Callaway, Duncan S.; Newman, M. E. J.; Strogatz, S. H.; Watts, D. J. (2000). "Network Robustness and Fragility: Percolation on Random Graphs". Physical Review Letters. 85: 5468–71. arXiv:cond-mat/0007300

. Bibcode:2000PhRvL..85.5468C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.5468.

. Bibcode:2000PhRvL..85.5468C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.5468. - ↑ Cohen, Reuven; Erez, Keren; ben-Avraham, Daniel; Havlin, Shlomo (2000). "Resilience of the Internet to Random Breakdowns". Physical Review Letters. 85 (21): 4626–4628. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.4626.

- ↑ Cohen, Reuven; Havlin, Shlomo (2003). "Scale-Free Networks Are Ultrasmall". Physical Review Letters. 90 (5). doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.90.058701.

- ↑ De Masi, Giulia; et. al (2006). "Fitness model for the Italian interbank money market". Physical Review E. 74: 066112. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.74.066112.

- ↑ Soramäki, Kimmo; et. al (2007). "The topology of interbank payment flows". Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications. 379 (1): 317–333. Bibcode:2007PhyA..379..317S. doi:10.1016/j.physa.2006.11.093.

- ↑ Steyvers, Mark; Joshua B. Tenenbaum (2005). "The Large-Scale Structure of Semantic Networks: Statistical Analyses and a Model of Semantic Growth". Cognitive Science. 29 (1): 41–78. doi:10.1207/s15516709cog2901_3.

- ↑ Fratini, Michela, Poccia, Nicola, Ricci, Alessandro, Campi, Gaetano, Burghammer, Manfred, Aeppli, Gabriel Bianconi, Antonio (2010). "Scale-free structural organization of oxygen interstitials in La2CuO4+y". Nature. 466 (7308): 841–4. arXiv:1008.2015

. Bibcode:2010Natur.466..841F. doi:10.1038/nature09260. PMID 20703301.

. Bibcode:2010Natur.466..841F. doi:10.1038/nature09260. PMID 20703301. - ↑ Poccia, Nicola, Ricci, Alessandro, Campi, Gaetano, Fratini, Michela, Puri, Alessandro, Di Gioacchino, Daniele, Marcelli, Augusto, Reynolds, Michael, Burghammer, Manfred, Saini, Naurang L., Aeppli, Gabriel Bianconi, Antonio, (2012). "Optimum inhomogeneity of local lattice distortions in La2CuO4+y". PNAS. 109 (39): 15685–15690. arXiv:1208.0101

. doi:10.1073/pnas.1208492109.

. doi:10.1073/pnas.1208492109. - ↑ Kumar, Ravi; Raghavan, Prabhakar (2000). Stochastic Models for the Web Graph (PDF). Foundations of Computer Science, 41st Annual Symposium on. pp. 57–65. doi:10.1109/SFCS.2000.892065.

- 1 2 Dangalchev Ch., Generation models for scale-free networks, Physica A 338, 659 (2004).

- ↑ Kasthurirathna, Dharshana; Piraveenan, Mahendra. (2015). "Emergence of scale-free characteristics in socioecological systems with bounded rationality". Scientific Reports. In Press.

- ↑ Barabási, A.-L. and R. Albert, Science 286, 509 (1999).

- ↑ R. Albert, and A.L. Barabási, Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 5234(2000).

- ↑ S. N. Dorogovtsev, J. F. F. Mendes, and A. N. Samukhim, cond-mat/0011115.

- 1 2 P.L. Krapivsky, S. Redner, and F. Leyvraz, Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 4629 (2000).

- ↑ B. Tadic, Physica A 293, 273(2001).

- ↑ S. Bomholdt and H. Ebel, cond-mat/0008465; H.A. Simon, Bimetrika 42, 425(1955).

- ↑ M. K. Hassan, Liana Islam and Syed Arefinul Haque, Degree distribution, rank-size distribution, and leadership persistence in mediation-driven attachment networks Physica A 469 23 (2017) http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.physa.2016.11.001.

- ↑ E. Ravasz and Barabási Phys. Rev. E 67, 026112 (2003).

- ↑ G. Caldarelli et al. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 258702 (2002).

- ↑ D. Garlaschelli et al. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93 , 188701 (2004).

- ↑ Krioukov, Dmitri; Papadopoulos, Fragkiskos; Kitsak, Maksim; Vahdat, Amin; Boguñá, Marián. "Hyperbolic geometry of complex networks". Physical Review E. 82 (3). doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.82.036106.

- ↑ A. Hernando; D. Villuendas; C. Vesperinas; M. Abad; A. Plastino (2009). "Unravelling the size distribution of social groups with information theory on complex networks". arXiv:0905.3704

[physics.soc-ph]., submitted to European Physics Journal B

[physics.soc-ph]., submitted to European Physics Journal B - ↑ André A. Moreira; Demétrius R. Paula; Raimundo N. Costa Filho; José S. Andrade, Jr. (2006). "Competitive cluster growth in complex networks". arXiv:cond-mat/0603272

[cond-mat.dis-nn].

[cond-mat.dis-nn].

Further reading

- Albert R.; Barabási A.-L. (2002). "Statistical mechanics of complex networks". Rev. Mod. Phys. 74: 47–97. arXiv:cond-mat/0106096

. Bibcode:2002RvMP...74...47A. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.74.47.

. Bibcode:2002RvMP...74...47A. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.74.47. - Amaral, LAN, Scala, A., Barthelemy, M., Stanley, HE. (2000). "Classes of behavior of small-world networks". PNAS. 97 (21): 11149–52. arXiv:cond-mat/0001458

. Bibcode:2000PNAS...9711149A. doi:10.1073/pnas.200327197. PMC 17168

. Bibcode:2000PNAS...9711149A. doi:10.1073/pnas.200327197. PMC 17168 . PMID 11005838.

. PMID 11005838. - Barabási, Albert-László (2004). Linked: How Everything is Connected to Everything Else. ISBN 0-452-28439-2.

- Barabási, Albert-László; Bonabeau, Eric (May 2003). "Scale-Free Networks" (PDF). Scientific American. 288 (5): 50–9. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0503-60.

- Dan Braha; Yaneer Bar-Yam (2004). "Topology of Large-Scale Engineering Problem-Solving Networks" (PDF). Phys. Rev. E. 69: 016113. Bibcode:2004PhRvE..69a6113B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.69.016113.

- Caldarelli G. "Scale-Free Networks" Oxford University Press, Oxford (2007).

- Caldarelli G.; Capocci A.; De Los Rios P.; Muñoz M.A. (2002). "Scale-free networks from varying vertex intrinsic fitness". Physical Review Letters. 89 (25): 258702. arXiv:cond-mat/0207366

. Bibcode:2002PhRvL..89y8702C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.89.258702. PMID 12484927.

. Bibcode:2002PhRvL..89y8702C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.89.258702. PMID 12484927. - R. Cohen, K. Erez, D. ben-Avraham and S. Havlin (2000). "Resilience of the Internet to Random Breakdowns". Phys. Rev. Lett. 85: 4626–8. arXiv:cond-mat/0007048

. Bibcode:2000PhRvL..85.4626C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.4626.

. Bibcode:2000PhRvL..85.4626C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.4626. - R. Cohen, K. Erez, D. ben-Avraham and S. Havlin (2001). "Breakdown of the Internet under Intentional Attack". Phys. Rev. Lett. 86: 3682–5. arXiv:cond-mat/0010251

. Bibcode:2001PhRvL..86.3682C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.86.3682. PMID 11328053.

. Bibcode:2001PhRvL..86.3682C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.86.3682. PMID 11328053. - A.F. Rozenfeld, R. Cohen, D. ben-Avraham, S. Havlin (2002). "Scale-free networks on lattices". Phys. Rev. Lett. 89. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.89.218701.

- Dangalchev, Ch. (2004). "Generation models for scale-free networks". Physica A. 338. doi:10.1016/j.physa.2004.01.056.

- Dorogovtsev, Mendes, J.F.F. , Samukhin, A.N. (2000). "Structure of Growing Networks: Exact Solution of the Barabási—Albert's Model". Phys. Rev. Lett. 85 (21): 4633–6. arXiv:cond-mat/0004434

. Bibcode:2000PhRvL..85.4633D. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.4633. PMID 11082614.

. Bibcode:2000PhRvL..85.4633D. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.4633. PMID 11082614. - Dorogovtsev, S.N., Mendes, J.F.F. (2003). Evolution of Networks: from biological networks to the Internet and WWW. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-851590-1.

- Dorogovtsev, S.N., Goltsev A. V., Mendes, J.F.F. (2008). "Critical phenomena in complex networks". Rev. Mod. Phys. 80: 1275. arXiv:0705.0010

. Bibcode:2008RvMP...80.1275D. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.80.1275.

. Bibcode:2008RvMP...80.1275D. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.80.1275. - Dorogovtsev, S.N., Mendes, J.F.F. (2002). "Evolution of networks". Advances in Physics. 51: 1079–1187. arXiv:cond-mat/0106144

. Bibcode:2002AdPhy..51.1079D. doi:10.1080/00018730110112519.

. Bibcode:2002AdPhy..51.1079D. doi:10.1080/00018730110112519. - Erdős, P.; Rényi, A. (1960). On the Evolution of Random Graphs (PDF). 5. Publication of the Mathematical Institute of the Hungarian Academy of Science. pp. 17–61.

- Faloutsos, M., Faloutsos, P., Faloutsos, C. (1999). "On power-law relationships of the internet topology". Comp. Comm. Rev. 29: 251. doi:10.1145/316194.316229.

- Li, L., Alderson, D., Tanaka, R., Doyle, J.C., Willinger, W. (2005). "Towards a Theory of Scale-Free Graphs: Definition, Properties, and Implications (Extended Version)". arXiv:cond-mat/0501169

[cond-mat.dis-nn].

[cond-mat.dis-nn]. - Kumar, R., Raghavan, P., Rajagopalan, S., Sivakumar, D., Tomkins, A., Upfal, E. (2000). "Stochastic models for the web graph" (PDF). Proceedings of the 41st Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science (FOCS). Redondo Beach, CA: IEEE CS Press. pp. 57–65.

- Manev R.; Manev H. (2005). "The meaning of mammalian adult neurogenesis and the function of newly added neurons: the "small-world" network". Med. Hypotheses. 64 (1): 114–7. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2004.05.013. PMID 15533625.

- Matlis, Jan (November 4, 2002). "Scale-Free Networks".

- Newman, Mark E.J. (2003). "The structure and function of complex networks". arXiv:cond-mat/0303516

[cond-mat.stat-mech].

[cond-mat.stat-mech]. - Pastor-Satorras, R., Vespignani, A. (2004). Evolution and Structure of the Internet: A Statistical Physics Approach. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-82698-5.

- Pennock, D.M., Flake, G.W., Lawrence, S., Glover, E.J., Giles, C.L. (2002). "Winners don't take all: Characterizing the competition for links on the web". PNAS. 99 (8): 5207–11. Bibcode:2002PNAS...99.5207P. doi:10.1073/pnas.032085699. PMC 122747

. PMID 16578867.

. PMID 16578867. - Robb, John. Scale-Free Networks and Terrorism, 2004.

- Keller, E.F. (2005). "Revisiting "scale-free" networks". BioEssays. 27 (10): 1060–8. doi:10.1002/bies.20294. PMID 16163729.

- Onody, R.N., de Castro, P.A. (2004). "Complex Network Study of Brazilian Soccer Player". Phys. Rev. E. 70: 037103. arXiv:cond-mat/0409609

. Bibcode:2004PhRvE..70c7103O. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.70.037103.

. Bibcode:2004PhRvE..70c7103O. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.70.037103. - Reuven Cohen; Shlomo Havlin (2003). "Scale-Free Networks are Ultrasmall". Phys. Rev. Lett. 90 (5): 058701. arXiv:cond-mat/0205476

. Bibcode:2003PhRvL..90e8701C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.90.058701. PMID 12633404.

. Bibcode:2003PhRvL..90e8701C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.90.058701. PMID 12633404. - Kasthurirathna, D., Piraveenan, M. (2015). "Complex Network Study of Brazilian Soccer Player". Sci. Rep. In Press.

External links

- snGraph Optimal software to manage scale-free networks.

- The Erdős Webgraph Server describing the hyperlink structure of a weekly updated, constantly increasing portion of the WWW.