Sarangi

| |

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| Related instruments | |

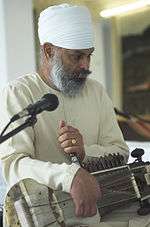

The sārangī (Nepali: सारङ्गी, Hindi: सारंगी, Urdu: سارنگی) is a bowed, short-necked string instrument from India as well as Nepal which is used in Hindustani classical music. It is the most popular musical instrument in Western part of Nepal and said to most resemble the sound of the human voice – able to imitate vocal ornaments such as gamaks (shakes) and meends (sliding movements).

History

There are different versions for the meaning and origins of "sarangi" The word "sarangi" could be a combination of two sanskrit words: "saar" (summary) and "ang" (form, herein different styles of playing instrumental music for e.g. "gayaki ang") hence meaning the instrument that can summarize every style of music or playing."Sarang" in fact has a number of meanings in Sanskrit.

According to some musicians, the word sarangi is a combination of two words ‘seh’(Persian equivalent of three) and ‘rangi’ (Persian equivalent of colored) corrupted as sarangi. The term seh-rangi represents the three melody strings. However the most common folk etymology is that sarangi is derived from 'sol rang'(a hundred colours) indicating its adaptability to many styles of vocal music, its flexible tunability, and its ability to produce a large palette of tonal colour and emotional nuance.

The repertoire of sarangi players is traditionally very closely related to vocal music. Nevertheless, a concert with a solo sarangi as the main item will sometimes include a full-scale raag presentation with an extensive alap (the unmeasured improvisatory development of the raga) in increasing intensity (alap-jor-jhala) and several compositions in increasing tempi called bandish. As such, it could be seen as being on a par with other instrumental styles such as sitar, sarod, and bansuri.

Sarangi music is often vocal music. It is rare to find a sarangi player who does not know the words of many classical compositions. The words are usually mentally present during performance, and performance almost always adheres to the conventions of vocal performance including the organisational structure, the types of elaboration, the tempo, the relationship between sound and silence, and the presentation of khyal and thumri compositions. The vocal quality of sarangi is in a quite separate category from, for instance, the so-called gayaki-ang of sitar which attempts to imitate the nuances of khyal while overall conforming to the structures and usually keeping to the gat compositions of instrumental music. (A gat is a composition set to a cyclic rhythm.)

The sarangi is also a traditional stringed musical instrument of Nepal, commonly played by the Gaine or Gandarbha ethnic group but the form and repertoire of sarangi is more towards the folk music as compared to the heavy and classical form of repertoire in India.

Structure

Carved from a single block of tun (red cedar) wood, the sarangi has a box-like shape with three hollow chambers: pet (stomach), chaati (chest) and magaj (brain). It is usually around 2 feet (0.61 m) long and around 6 inches (150 mm) wide though it can vary as there are smaller as well as larger variant sarangis as well. The lower resonance chamber or pet is covered with parchment made out of goat skin on which a strip of thick leather is placed around the waist (and nailed on the back of the chamber) which supports the elephant-shaped bridge that is made of camel or buffalo bone usually (made of ivory or Barasingha bone originally but now that is rare due to the ban in India). The bridge in turn supports the huge pressure of approximately 35–37 sympathetic steel or brass strings and three main gut strings that pass through it. The three main playing strings – the comparatively thicker gut strings – are bowed with a heavy horsehair bow and "stopped" not with the finger-tips but with the nails, cuticles and surrounding flesh. (talcum powder is applied to the fingers as a lubricant). The neck has ivory/bone platforms on which the fingers slide. The remaining strings are resonance strings or tarabs (see: sympathetic strings), numbering up to around 35–37, divided into 4 "choirs" having two sets of pegs, one on the right and one on the top. On the inside is a chromatically tuned row of 15 tarabs and on the right a diatonic row of 9 tarabs each encompassing a full octave plus 1–3 extra notes above or below that. Both these sets of tarabs pass from the main bridge to the right side set of pegs through small holes in the chaati supported by hollow ivory/bone beads. Between these inner tarabs and on the either side of the main playing strings lie two more sets of longer tarabs, with 5–6 strings on the right set and 6–7 strings on the left set. They pass from the main bridge over to two small, flat and wide table like bridges through the additional bridge towards the second peg set on top of the instrument. These are tuned to the important tones (swaras) of the raga. A properly tuned sarangi will hum and cry and will sound like melodious meowing, with tones played on any of the main strings eliciting echo-like resonances. A few sarangis use strings manufactured from the intestines of goats — these harken back to the days when rich musicians could afford such strings.

Makers

- Tabla Sitar Musicals (Delhi)

- Masita (Meerut)

- Behra (Meerut)

- Rajesh Dhawan (Meerut)

- Raj Musicals (New Delhi)

- Krishna Gopal Manandhar (Nepal)

Modern performers who have used sarangi in compositions

- A. R. Rahman for the song "Tum Ko" performed by Kavita Krishnamurthy in the feature film Rockstar Sarangi played by Dilshad Khan.

- Yuvan Shankar Raja for the song "Yogi theme in saarangi" in his 2009 film "Yogi", performed by "Ustad Sultan Khan".

- Hiphop Tamizha for the song "Indru Netru Naalai" in "Indru Netru Naalai".

- Anirudh for the song "Neeyum Naanum" in Naanum Rowdy Dhaan 2015 film, performed by "Manonmani".

- Aerosmith, sarangi parts performed by Ramesh Mishra (featured on the track "Taste of India" from the 1997 album Nine Lives)

- Surinder Sandhu, The Fictionist with The Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra, SauRango Orchestra with Steve Vai and Cycles and Stories.

- Cheb i Sabbah

- Def Leppard in "Turn to Dust" from 1996 album Slang (album)

- Howard Shore (the Lothlórien portions of the score for The Fellowship of the Ring)

- Nitin Sawhney

- Robert Miles (on his 2001 album Organik)

- Secret Chiefs 3

- Steve Shelley of Sonic Youth

- Tabla Beat Science

- Tool (featured on the track "Reflection")

- Talvin Singh

- Robin Williamson of the Incredible String Band (notably in the song White Bird on the Changing Horses album)

- Blind Melon's track Sleepyhouse from their debut album Blind Melon

- Laage Re Nain Coke Studio Season 6

- Pagal [Coke Studio] Season 6 -Winit Tikko band Sarangi By Sharukh Khan

- Ram Narayan

- Aruna Narayan

- Jon Foreman of Switchfoot for the song "She Said" on his 2015 solo EP, The Wonderlands: Darkness

- Ahsan Ali (National Anthem on Sarangi )

See also

References

Bor, Joep, 1987: The Voice of the Sarangi, comprising National Centre for the Performing Arts Quarterly Journal 15 (3-4), December 1986 and March 1987 ( special combined issue), Bombay: NCPA

Magriel, Nicolas, 1991 Sarangi Style in North Indian Music, (unpublished PhD thesis),London: University of London}

Qureshi, Regula Burckhardt, 1997: “The Indian Sarangi: Sound of Affect, Site of Contest”, Yearbook for Traditional Music, pp. 1-38

Sorrell, Neil (with Ram Narayan), 1980: Indian Music in Performance, Bolton: Manchester University Press

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sarangis. |

- Resham Firiri A popular Nepali folk music with a Sarangi and madal.

- sarangi.info – downloadable sarangi and vocal music, including the integral of two important books, The Voice of the Sarangi by Joep Bor and Indian Music in Performance and Practice by Ram Narayan and Neil Sorrell.

- Growing into Music – includes several films by Nicolas Magriel on Indian musical enculturation including films about the sarangi players Sarwar Hussain Khan, Vidya Sahai Mishra and Kanhaiyalal Mishra.

- Nepali Sarangi Video from YouTube

Three historic sarangi from The Metropolitan Museum of Art