Sarah Josepha Hale

| Sarah Josepha Hale | |

|---|---|

Sarah Josepha Hale, 1831, by James Reid Lambdin | |

| Born |

October 24, 1788 Newport, New Hampshire |

| Died |

April 30, 1879 (aged 90) Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Occupation | Poet, editor, author |

Sarah Josepha Buell Hale (October 24, 1788 – April 30, 1879) was an American writer and an influential editor. She is the author of the nursery rhyme "Mary Had a Little Lamb". Hale famously campaigned for the creation of the American holiday known as Thanksgiving, and for the completion of the Bunker Hill Monument.

Early life and family

Sarah Josepha Buell was born in Newport, New Hampshire, to Captain Gordon Buell and Martha Whittlesay Buell. Her parents believed in equal education for both genders.[1] Home-schooled by her mother and elder brother Horatio (who had attended Dartmouth), Hale was otherwise an autodidact.

As Sarah Buell grew up and became a local schoolteacher, in 1811 her father opened a tavern called The Rising Sun in Newport. Sarah met lawyer David Hale the same year.[2] The couple married at The Rising Sun on October 23, 1813,[2] and ultimately had five children: David (1815), Horatio (1817), Frances (1819), Sarah (1820) and William (1822).[3] David Hale died in 1822,[4] and Sarah Josepha Hale wore black for the rest of her life as a sign of perpetual mourning.[1][5]

Career

In 1823, with the financial support of her late husband's Freemason lodge, Sarah Hale published a collection of her poems titled The Genius of Oblivion.

Four years later, in 1827, her first novel was published in the U.S. under the title Northwood: Life North and South and in London under the title A New England Tale. The novel made Hale one of the first novelists to write a book about slavery, as well as one of the first American woman novelists. The book also espoused New England virtues as the model to follow for national prosperity, and was an immediate success.[5] The novel supported relocating the nation's African slaves to freedom in Liberia. In her introduction to the second edition (1852), Hale wrote; "The great error of those who would sever the Union rather than see a slave within its borders, is, that they forget the master is their brother, as well as the servant; and that the spirit which seeks to do good to all and evil to none is the only true Christian philanthropy." The book described how while slavery hurts and dehumanizes slaves absolutely, it also dehumanizes the masters and retards their world's psychological, moral and technological progress.

Reverend John Blake praised Northwood, and asked Hale to move to Boston to serve as the editor of his journal, the Ladies' Magazine.[6] She agreed and from 1828 until 1836 served as editor in Boston, though she preferred the title "editress".[1] Hale hoped the magazine would help in educating women, as she wrote, "not that they may usurp the situation, or encroach on the prerogatives of man; but that each individual may lend her aid to the intellectual and moral character of those within her sphere".[5] Her collection Poems for Our Children, which includes "Mary Had a Little Lamb" (originally titled "Mary's Lamb"), was published in 1830.[7][8] The poem was written for children, an audience for which many women poets of this period were writing.[9]

Hale founded the Seaman's Aid Society in 1833 to assist the surviving families of Boston sailors who died at sea.[10]

Louis Antoine Godey of Philadelphia wanted to hire Hale as the editor of his journal Godey's Lady's Book. He bought the Ladies' Magazine, now renamed American Ladies' Magazine, and merged it with his journal. In 1837, Hale began working as editor of the expanded Godey's Lady's Book, but insisted she edit from Boston while her youngest son, William, attended Harvard College.[11] She remained editor at Godey's for forty years, retiring in 1877 when she was almost 90.[12] During her tenure at Godey's, several important women contributed poetry and prose to the magazine, including Lydia Sigourney, Caroline Lee Hentz, Elizabeth F. Ellet, and Frances Sargent Osgood.[13] Other notable contributors included Nathaniel Hawthorne, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Washington Irving, James Kirke Paulding, William Gilmore Simms, and Nathaniel Parker Willis.[14] During this time, she became one of the most important and influential arbiters of American taste.[15] In its day, Godey's, with no significant competitors, had an influence unimaginable for any single publication in the 21st century. The magazine is credited with an ability to influence fashions not only for women's clothes, but also in domestic architecture. Godey's published house plans that were copied by home builders nationwide.

During this time, Hale wrote many novels and poems, publishing nearly fifty volumes by the end of her life. Beginning in the 1840s, she also edited several issues of the annual gift book The Opal.

Final years and death

Hale retired from editorial duties in 1877 at the age of 89. The same year, Thomas Edison spoke the opening lines of "Mary's Lamb" as the first speech ever recorded on his newly invented phonograph.[16] Hale died at her home, 1413 Locust Street in Philadelphia, on April 30, 1879.[17] A blue historical marker exists at 922 Spruce St. She is buried in a simple grave in the Laurel Hill Cemetery in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.[18]

Beliefs

Hale, as a successful and popular editor, was respected as an arbiter of taste for middle-class women in matters of fashion, cooking, literature, and morality.[1] In her work, however, she reinforced stereotypical gender roles, specifically domestic roles for women,[5] while casually trying to expand them.[1] For example, Hale believed that women shaped the morals of society, and pushed for women to write morally uplifting novels. She wrote that "while the ocean of political life is heaving and raging with the storm of partisan passions among the men of America... [women as] the true conservators of peace and good-will, should be careful to cultivate every gentle feeling".[19] Hale did not support women's suffrage and instead believed in the "secret, silent influence of women" to sway male voters.[20]

Hale advocated education, and ultimately women's entry into the work force. She supported play and physical education as important learning experiences for children. In 1829, Hale wrote, "Physical health and its attendant cheerfulness promote a happy tone of moral feeling, and they are quite indispensable to successful intellectual effort."[21] Hale became an early advocate of higher education for women,[22] and helped to found Vassar College.[1] Her championship of women's education began as Hale edited the Ladies' Magazine and continued until she retired. Hale wrote no fewer than seventeen articles and editorials about women's education, and helped make founding an all-women's college acceptable to a public unaccustomed to the idea.[23] In 1860, the Baltimore Female College awarded Hale a medal "for distinguished services in the cause of female education".[24] Furthermore, as an editor beginning in 1852, Hale created a section headed "Employment for Women" discussing women's attempts to enter the workforce.[10] Hale also published the works of Catharine Beecher, Emma Willard and other early advocates of education for women.

Hale also became a strong advocate of the American nation and union. In the 1820s and 1830s, as other American magazines merely compiled and reprinted articles from British periodicals, Hale was among the leaders of a group of American editors who insisted on publishing American writers. In practical terms, this meant that she sometimes personally wrote half of the material published in the Ladies' Magazine. In later years, it meant that Hale particularly liked to publish fiction with American themes, such as the frontier, and historical fiction set during the American Revolution. Hale adamantly opposed slavery and was strongly devoted to the Union. She used her pages to campaign for a unified American culture and nation, frequently running stories in which southerners and northerners fought together against the British, or in which a southerner and a northerner fell in love and married.

Legacy

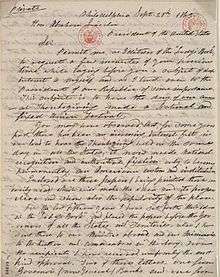

Hale may be the individual most responsible for making Thanksgiving a national holiday in the United States; it had previously been celebrated only in New England.[25] Each state scheduled its own holiday, some as early as October and others as late as January; it was largely unknown in the American South. Her advocacy for the national holiday began in 1846 and lasted 17 years before it was successful.[26] In support of the proposed national holiday, Hale wrote letters to five Presidents of the United States: Zachary Taylor, Millard Fillmore, Franklin Pierce, James Buchanan, and Abraham Lincoln. Her initial letters failed to persuade, but the letter she wrote to Lincoln convinced him to support legislation establishing a national holiday of Thanksgiving in 1863.[27] The new national holiday was considered a unifying day after the stress of the American Civil War.[28] Before Thanksgiving's addition, the only national holidays celebrated in the United States were Washington's Birthday and Independence Day.[29]

Hale also worked to preserve George Washington's Mount Vernon plantation, as a symbol of patriotism that both the Northern and Southern United States could all support.[30]

Hale raised $30,000 in Boston for the completion of the Bunker Hill Monument.[12][31] When construction stalled, Hale asked her readers to donate a dollar each and also organized a week-long craft fair at Quincy Market.[31] Described as "'Oprah and Martha Stewart combined,'" Hale's organization of the giant craft fair at Quincy Market "was much more than a "bake sale" — "refreshments were sold ... but they brought in only a fraction of the profit."[31] The fair sold handmade jewelry, quilts, baskets, jams, jellies, cakes, pies, and autographed letters from Washington, James Madison, and the Marquis de Lafayette.[31][32] Hale "made sure the 221-foot obelisk that commemorates the battle of Bunker Hill got built."[31]

Liberty Ship #1538 (1943–1972) was named in Hale's honor, as was a New York City Board of Education vocational high school on the corner of Dean St. and 4th Avenue in Brooklyn, New York. However, the school closed in June 2001.

A prestigious literary prize, the Sarah Josepha Hale Award, is named for her.[33]

Hale was further honored as the fourth in a series of historical bobblehead dolls created by the New Hampshire Historical Society and sold in their museum store in Concord, New Hampshire.[34]

Hale is honored with a feast day on the liturgical calendar of the Episcopal Church (USA) on April 30. She is commemorated on the Boston Women's Heritage Trail.[35]

Selected works

- The Genius of Oblivion; and Other Original Poems. J. B. Moore. 1823.

- Northwood. Bowles & Dearborn. 1827.

- Traits of American Life. E.L. Carey & A. Hart. 1835.

- Sketches of American character. H. Perkins. 1838.

- The Good Housekeeper. Weeks, Jordan. 1839.

- Northwood, or Life North and South. H. Long & Brother. 1852.

- Liberia; or, Mr. Peyton's Experiments (1853)

- Flora's Interpreter; or, The American Book of Flowers and Sentiments. B. Mussey. 1853.

- The new household receipt-book. T Nelson & Son. 1854.

- Woman's Record: or Sketches of All Distinguished Women, from Creation to A.D. 1854. Harper & Bros. 1855.

- Sarah Josepha Buell Hale, ed. (1849). Aunt Mary's new stories for young people. J. Munroe & Company.

- Manners; or, Happy Homes and Good Society. J. E. Tilton and Company. 1868.

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Howe, Daniel Walker. What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815–1848. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007: 608. ISBN 978-0-19-507894-7

- 1 2 Parker, Gail Underwood. More Than Petticoats: Remarkable New Hampshire Women. Guilford, CT: Globe Pequot, 2009: 25. ISBN 978-0-7627-4002-4

- ↑ Parker, Gail Underwood. More Than Petticoats: Remarkable New Hampshire Women. Guilford, CT: Globe Pequot, 2009: 26–27. ISBN 978-0-7627-4002-4

- ↑ Douglas, Ann. The Feminization of American Culture. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1977: 332. ISBN 0-394-40532-3

- 1 2 3 4 Rose, Anne C. Transcendentalism as a Social Movement, 1830–1850. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1981: 24. ISBN 0-300-02587-4

- ↑ Parker, Gail Underwood. More Than Petticoats: Remarkable New Hampshire Women. Guilford, CT: Globe Pequot, 2009: 27–28. ISBN 978-0-7627-4002-4

- ↑ Nelson, Randy F. The Almanac of American Letters. Los Altos, California: William Kaufmann, Inc., 1981: 283. ISBN 0-86576-008-X

- ↑ Wilson, Susan. Literary Trail of Greater Boston. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2000: 24. ISBN 0-618-05013-2

- ↑ Watts, Emily Stipes. The Poetry of American Women from 1632 to 1945. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press, 1978: 94. ISBN 0-292-76450-2

- 1 2 O'Connor, Thomas H. Civil War Boston: Home Front and Battlefield. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1997: 8. ISBN 1-55553-318-3

- ↑ Parker, Gail Underwood. More Than Petticoats: Remarkable New Hampshire Women. Guilford, CT: Globe Pequot, 2009: 29–30. ISBN 978-0-7627-4002-4

- 1 2 Oberholtzer, Ellis Paxson. (1906) The Literary History of Philadelphia. Philadelphia: George W. Jacobs & Co.: 230.

- ↑ Mott, Frank Luther. A History of American Magazines. Cambridge, MA: Published by Harvard University Press, 1930: 584.

- ↑ Oberholtzer, Ellis Paxson. The Literary History of Philadelphia. Philadelphia: George W. Jacobs & Co., 1906: 231.

- ↑ Douglas, p. 94.

- ↑ Parker, Gail Underwood. More Than Petticoats: Remarkable New Hampshire Women. Guilford, CT: Globe Pequot, 2009: 35. ISBN 978-0-7627-4002-4

- ↑ Ehrlich, Eugene and Gorton Carruth. The Oxford Illustrated Literary Guide to the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1982: 205. ISBN 0-19-503186-5

- ↑ Sarah Josepha Hale at Find a Grave

- ↑ Riley, Glenda. Women and Indians on the Frontier, 1825–1915. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, 1984: 8. ISBN 0-8263-0780-9

- ↑ Parker, Gail Underwood. More Than Petticoats: Remarkable New Hampshire Women. Guilford, CT: Globe Pequot, 2009: 33. ISBN 978-0-7627-4002-4

- ↑ Park, Roberta J. "Embodied Selves: The Rise and Development of Concern for Physical Education, Active Games and Recreation for American Women, 1776–1865", Sport in America: From Wicked Amusement to National Obsession, David Kenneth Wiggins, editor. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 1995: 80. ISBN 0-87322-520-1

- ↑ Von Mehren, Joan. The Minerva and the Muse: A Life of Margaret Fuller. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 1994: 166. ISBN 1-55849-015-9

- ↑ Vassar Female College and Sarah Josepha Hale - Vassar College Encyclopedia

- ↑ Parker, Gail Underwood. More Than Petticoats: Remarkable New Hampshire Women. Guilford, CT: Globe Pequot, 2009: 31. ISBN 978-0-7627-4002-4

- ↑ Appelbaum, Diana Karter. Thanksgiving: An American Holiday, An American History. New York, Facts on File, 1984

- ↑ Schenone, Laura. A Thousand Years Over A Hot Stove: A History Of American Women Told Through Food, Recipes, And Remembrances. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2004: 118. ISBN 978-0-393-32627-7

- ↑ Wilson, Susan. Literary Trail of Greater Boston. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 200: 23. ISBN 0-618-05013-2

- ↑ Schenone, Laura. A Thousand Years Over A Hot Stove: A History Of American Women Told Through Food, Recipes, And Remembrances. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2004: 119. ISBN 978-0-393-32627-7

- ↑ Smith, Andrew F. The Turkey: An American Story. University of Illinois Press, 2006: 74. ISBN 978-0-252-03163-2

- ↑ Howe, Daniel Walker. What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815–1848. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007: 609. ISBN 978-0-19-507894-7

- 1 2 3 4 5 Abby Goodnough, "Living History at National Landmarks: Championing An Unsung Hero", New York Times, National Section p. 10, Sunday, July 4, 2010. Found at Times archives. Accessed August 10, 2010.

- ↑ Parker, Gail Underwood. More Than Petticoats: Remarkable New Hampshire Women. Guilford, CT: Globe Pequot, 2009: 24. ISBN 978-0-7627-4002-4

- ↑ Sarah Josepha Hale Award, Richards Free Library

- ↑ NH Historical Society

- ↑ "Sarah Josepha Hale". Boston Women's Heritage Trail.

Further reading

- Anderson, Laurie Halse. Thank You, Sarah: The Woman Who Saved Thanksgiving. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2002. ISBN 0-689-85143-X

- Baym, Nina. "Onward Christian Women: Sarah J. Hale's History of the World", The New England Quarterly. Vol. 63, No. 2, p. 249. June 1990.

- Dubois, Muriel L. To My Countrywomen: The Life of Sarah Josepha Hale. Bedfored, New Hampshire: Apprentice Shop Books, 2006. ISBN 978-0-9723410-1-1

- Finley, Ruth Elbright. The Lady of Godey's. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1931.

- Fryatt, Norma R. Sarah Josepha Hale: The Life and Times of a Nineteenth-Century Woman. New York: Hawthorn Books, 1975. ISBN 0-8015-6568-5

- Mott, Frank Luther. A History of American Magazines. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1968.

- Okker, Patricia. Our Sister Editors: Sarah J. Hale and the Tradition of Nineteenth-century American Women Editors. Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press, 1995.

- Rogers, Sherbrooke. Sarah Josepha Hale: A New England Pioneer, 1788-1879. Grantham, New Hampshire: Tompson & Rutter, 1985. ISBN 0-936988-10-X

- Tonkovich, Nicole. Domesticity with a Difference: The Nonfiction of Catharine Beecher, Sarah J. Hale, Fanny Fern, and Margaret Fuller. Jackson, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi, 1997. ISBN 0-87805-993-8

External links

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Sarah Josepha Hale |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sarah Josepha Hale. |

- Sarah Hale: The Mother of Thanksgiving Audio slide show: Historian Anne Blue Wills tells the story of Sarah Hale on "BackStory with the American History Guys"

- Lehigh.edu, Etext Library: Sarah Josepha Hale

- Woman Writers: Sarah Josepha Hale

- Spring Flowers by Sarah Josepha Hale from the University of Florida Digital Collections