San Lazzaro degli Armeni

|

Aerial view of the island in 2013  San Lazzaro degli Armeni circled in red | |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 45°24′43″N 12°21′41″E / 45.411979°N 12.361422°ECoordinates: 45°24′43″N 12°21′41″E / 45.411979°N 12.361422°E |

| Adjacent bodies of water | Venetian Lagoon |

| Area | 3 ha (7.4 acres)[1] |

| Administration | |

| Region | Veneto |

| Province | Province of Venice |

| Commune | Venice |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 17 (2015)[lower-alpha 1] |

| Ethnic groups | Armenians |

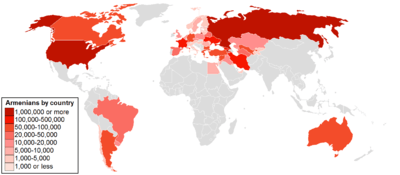

San Lazzaro degli Armeni (Italian: [ˈsan ˈladdzaro ˈdeʎʎ arˈmeːni]; lit. "Saint Lazarus of the Armenians",[3][4] Armenian: Սուրբ Ղազար, Surb Ghazar)[lower-alpha 2] is a small island in the Venetian Lagoon, northern Italy. It lies to the southeast of Venice and immediately west of the Lido and covers an area of 3 hectares (7.4 acres).[1]

A leper colony during the Middle Ages, the island has been home to the Armenian Catholic Monastery of San Lazzaro[lower-alpha 3] since 1717.[6] It is the headquarters of the Mechitarist Order and, as such, one of the world's prominent centers of Armenian culture[7] and Armenian studies.[8] From the late 18th century to the early 20th century it was a major center of Armenian printing.

The island is one of the best known historic sites of the Armenian diaspora.[9] The monastery has a large collection of books, journals, artifacts, and the third largest collection of Armenian manuscripts. Over the centuries, dozens of artists, writers, political and religious leaders have visited the island. Nowadays, it attracts tens of thousands of tourists annually.[10]

History

Middle Ages

In 810 the Republic of Venice allocated the island to the abbot of the Benedictine Monastery of St. Ilario of Fusina.[12] In 1182 a leper colony (hospital for people with leprosy) was established at the island.[12] It was chosen for a leper colony since the island is relatively far away from the principal islands forming the city of Venice. It received its name from St. Lazarus, the patron saint of lepers.[13] In 1348 the leper colony was renovated and a church dedicated to San Lazzaro was built.[12] The hospital was moved to Venice in 1595 and the island was gradually abandoned.[14] In the 17th century the island was leased to various religious groups.[14] By the early 18th century only a "few crumbling ruins" remained in the isle.[13]

Armenian period

18th-19th centuries

In 1701 Mkhitar Sebastatsi (Mechitar or Mekhitar), an Armenian Catholic monk, founded a Catholic order in Constantinople that would later be called after him.[16] The order moved to Modon (Methoni) in the Green peninsula of Peloponnese in 1703,[17] after repressions by the Ottoman government and the Armenian Apostolic Church. In 1711 the order received recognition by Pope Clement XI.[16] In April 1715, a group of twelve Armenian Catholic monks led by Mkhitar Sebastatsi arrived in Venice from Morea, Peloponnese, following its invasion by the Ottoman Empire.[18] The Venetian Admiral Mocenigo and Governor of Morea, Angelo Emo "sympathizing deeply with the fearful distress of the unfortunate community, yielded to their earnest entreaties for permission to embark on a government vessels which was about to leave for Venice."[17]

On September 8, 1717, the Venetian Senate ceded the island of St. Lazarus to the Mechitarist order. "The Armenian Monks at once hastened to occupy the ruins on the Island... and the Abbot ordered the most necessary repairs to be at once made on the crumbling and dilapidated buildings which still remained."[19] The Armenian monks were required not to rename the island.[14] Upon acquisition the construction of a two-storey Armenian monastery began. The preexisting church of St. Lazarus was renovated. Gardens, residency buildings, a seminary and other structures were constructed.[14] The construction of the monastery was completed by 1740.[20] Mkhitar Sebastatsi died in 1749[21] and was succeeded by Stepanos Melkonian of Constantinople whose tenure as abbot ended 1799.[22]

The Venetian Republic was disestablished by Napoleon in 1797, however, the Mechitarist congregation was "left in peace",[23] allegedly because of the "presence of an indispensable Armenian official in Naopleon's secretariat."[24] In 1810 Napoleon signed a decree, which declared the congregation may continue to exist as an academy.[22][25]

The island has been enlarged several times. In 1815 by the permission of the Austrian Empire the island's size doubled from around 7,200 m2 (77,500 sq ft) to 14,400 m2 (155,000 sq ft).[14]

During the 1848 revolutions in the Italian states a small garrison was stationed at the island.[26]

William Dean Howells described the island and the monastery in 1866 as follows: "As a seat of learning, San Lazzaro is famed throughout the Armenian world, and gathers under its roofs the best scholars and poets of that nation. In the press of the convent books are printed in some thirty different languages; and a number of the fathers employ themselves constantly in works of transition."[27]

20th century and beyond

The island was enlarged twice in the first half of the twentieth century. First, in 1912 the old canal was filled in and the shoreline was straightened. Following the Second World War, between 1947 and 1949 significant land was reclaimed in the southeastern and southwestern sides of the island. Furthermore, a wall was built around the shore. A fire broke out in 1975, which partially destroyed the library and damaged the church, and destroyed two Gaspare Diziani paintings. Between 2002 and 2004, an extensive restoration of the monastery's structures was carried out by the funding of the Italian government.[12]

Current state

Currently, somewhere between 17,[2] 24,[28] or 30+ people reside on the island, including monks, seminarians and students.[29][30][31]

The island may be reached by a vaporetto from the San Zaccaria station.[32] There are tours in several different languages.[30][31] According to a 2007 article some 40,000 people visit the island annually,[10] mostly non-Armenians with Italians making up the majority of visitors.[2]

The monastery

.jpg)

The island currently contains a church with a neo-Gothic interior, a tall onion-shaped campanile (bell tower),[lower-alpha 4] residential quarters, library, museum, picture gallery, manuscript repository, printing plant, sundry teaching and research facilities,[16] gardens, a bronze statue of Mkhitar sculpted by Antonio Baggio in 1962,[12] an Armenian Genocide memorial erected in the 1960s,[34] a 14th-century khachkar donated by the Armenian government in 1987.[12] The gardens of the monastery have been admired by many visitors.[35][36][37] One author wrote in 1905: "The island [...] with its flower and fruit gardens, is so well kept that an excursion to San Lazzaro is a favourite one with all visitors to Venice."[38]

Collections

In the mid-19th century an English publication wrote that "the convent may be regarded as a species of metropolis of Armenian literature."[39][lower-alpha 5] The library contains 150,000[1][41] to 200,000 printed books and periodicals.[2][42]

- Manuscripts

The rotunda-shaped manuscript repository (manuscript library), built in 1970,[1] contains some 3,000[43] to 4,000[31][44] medieval Armenian manuscripts, making it the third largest[37][43] collection of Armenian manuscripts in the world after Matenadaran in Yerevan, Armenia (11,000 in the strict sense[43] to 17,000 in total)[45] and the Armenian Patriarchate of Jerusalem (3,890).[43] The earliest manuscripts preserved at the repository date to the eighth century.[46][44] It holds one of the ten[47] extant copies of Urbatagirk, the first-ever Armenian book printed by Hakob Meghapart in Venice in 1512.[48] Furthermore, 44 Armenian prayer scrolls (hmayil) are preserved at the repository.[49] The ceiling of the manuscript repository was painted by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo.[46]

- Museum

Besides books and manuscripts, there are various oriental artifacts at the museum,[50] which include an Egyptian mummy, Etruscan vases, Chinese antiques, an Indian throne, and other items.[51] The mummy is attributed to Namenkhet Amun, a priest at the Amon Temple in Karnak. It was sent to San Lazzaro in 1825 by Boghos Bey Yusufian, an Egyptian minister of Armenian origin. Radiocarbon dating revealed that it dates to 450-430 BC (Late Period of ancient Egypt).[52] The museum also preserves the sword of Leo V, the last Armenian King of Cilicia, forged in 1366 and stamps issued by the 1918-20 First Republic of Armenia.[2]

Publishing house

Armen Kalfayan wrote in 1935 that the island "has long been a veritable beehive of Armenian literary activity."[53] A publishing house was established at the monastery in 1789. In the early 19th century, a number of important publications were made on the island,[54] including a seminal two-volume dictionary of Classical Armenian (Նոր Բառգիրք Հայկազեան Լեզուի, 1836-7), which remains "unsurpassed".[54] Beginning in 1800 a periodical journal has been published at the island. Bazmavep, a literary, historical and scientific journal, was established in 1843 and continues to be published to this day.[55] The printing press at San Lazzaro is the oldest continuously operating Armenian publishing house in the world.[56] Nathaniel Colgan wrote in 1878 that the printing-office is the "great boast of the monastery."[57]

Significance

Sometimes called a "little Armenia",[lower-alpha 6] the island is one of the Armenian diaspora's "richest enclaves of culture".[62] The New York Times wrote in 1919: "For more than two centuries this island has been an Armenian oasis transplanted to the Venetian lagoon."[63] The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church calls the convent of San Lazzaro and the order of the Mechitarists "especially remarkable" of the religious orders based in Venice.[64] It has been described as "the headquarters of the Armenians scattered over Europe, and especially of those in Italy."[65]

Mary M. Tarzian suggests that Armenian nationalism among Armenians in the Ottoman Empire emerged from the educational vision of the Mechitarists in San Lazzaro.[66] Charles Yriarte wrote in 1877 that the Armenians "look with justice upon the island of San Lazzaro as the torch which shall one day illuminate Armenia, when the hour comes for her to live again in history and to take her place once more among free nations."[67] Italian scholar Matteo Miele compared the work of the Mekhitarists carried out in the island to the work of the humanists, painters and sculptors of the Italian Renaissance.[68] Nathaniel Colgan wrote in 1878 that monastery is "inhabited by an order of monks whose labours are devoted to the spread of European culture among the Armenian Christians."[57]

According to Robert H. Hewsen the monastery of San Lazzaro "for a full century was the only center of intensive Armenian cultural activity that the Armenians possessed" and until the establishment of the Lazarev Institute in Moscow in 1815 "the heritage of the Armenian people lay almost entirely in the hands of the Mekhitarists" in San Lazzaro.[69]

- In literature

The prominent Armenian poet Hovhannes Shiraz wrote a poem about the island: "An Armenian island in the foreign waters, / You rekindle the old light of Armenia... / Outside the homeland, for the sake of the homeland."[70]

- Artistic depictions

Numerous artists have painted the island, including Gevorg Bashinjaghian (Island of Surb Ghazar at night, 1892),[58] Ivan Aivazovsky (Byron's visit to the Mekhitarists in Surb Ghazar Island, 1899),[71] Joseph Pennell (The Armenian convent, 1905) [72] and Hovhannes Zardaryan (Sb. Ghazar island, Venice, 1958)[73]

Rose jam

The Mechitarist monks at San Lazzaro are known for making jam from rose petal around May, when the roses are in full bloom. Besides rose petal, it contains white caster sugar, water, and lemon juice.[74] It is called Vartanush[75][76] (Western Armenian pronunciation of վարդանուշ, vardanush literally translating to "sweet rose"; also a female given name). Around five thousand jars of jam are made and sold in the gift shop in the island. Monks also eat it for breakfast.[77]

Notable visitors and residents

- Residents

Mkhitar Sebastatsi (Mekhitar or Mechitar), the founder of the Mechitarist Order, lived in the island from 1717 until his death in 1749. Mikayel Chamchian (1738–1823), who wrote a comprehensive and influential history of Armenia which was used as a reference work by scholars for over a century, lived in the island since 1757.[78] Ghevont Alishan, a prominent historian, was a member of the Mechitarist Order since 1838. In 1849-51 he edited the journal Bazmavep and taught at the monastic seminary in 1866-72.[79] He lived in the island permanently from 1872 until his death in 1901.[80] Gabriel Aivazovsky (1812-1880), a philologist, historian and publisher, studied at the island school from 1826 to 1830 and was later the secretary of the Mekhitarian congregation. He founded and edited the San Lazzaro-based journal Bazmavep from 1843 to 1848.[81]

Ethnographer Yervand Lalayan worked at the island for around six months in 1894.[82]

Hrant Maloyan, a Syrian Armenian military serviceman and politician, received his education at the island in 1905-07.[83]

Giovanni Beltrame (1824-1906), Italian missionary and geographer[84]

- Visitors

A wide range of notable individuals have visited the island through centuries. Pope Pius VII visited the island on May 9, 1800 and elevated Stepanos Akonz Köver, who was elected abbot, to the rank of bishop.[22]

.jpg)

English Romantic poet Lord Byron lived in the island from late 1816 to early 1817. He signed his name in a book first time on November 27, 1816.[85] By early 1817 Byron had acquired enough Armenian to translate passages from Classical Armenian into English.[86] He co-authored English Grammar and Armenian in 1817, and Armenian Grammar and English in 1819, where he included quotations from classical and modern Armenian.[87] Byron is considered the most prominent of all visitors of the island.[88] The room where Byron studied now bears his name and is cherished by the monks.[36][88] There is also a plaque commemorating Byron's stay.[37][89] Nathaniel Colgan wrote in 1878: "Byron spent three months in San Lazzaro, where he came to study Armenian in 1816; and the monks seem to cherish his memory with peculiar fondness. The room he occupied is shown with pride, his manuscripts, his ink-stand, his Armenian exercise-book are all carefully preserved, and a few stumpy quills he made use of are still "hung up as monuments."[57]

In the 19th century a number of renowned composers such as Gioachino Rossini (1800s)[90] and Richard Wagner (1859)[91] and also writers, novelists and poets (Lady Morgan, 1820;[92] Alfred de Musset, 1834;[93][94] George Sand, July 1834;[95] Catharine Sedgwick, 1839;[96] William Cullen Bryant, 1853;[97] William Dean Howells, 1861;[98] Helen Hunt Jackson, 1869;[99] Marcel Proust, 1900;[100] Edgar Fawcett, 1900)[101] visited the island. European scholars such as German orientalists Julius Heinrich Petermann[14] and Friedrich Windischmann visited in 1833.[102] Other notable visitors include British art critic John Ruskin (early 1850s),[103] French historian Victor Langlois (1850s),[90] French philosopher and historian Ernest Renan (1850),[90] American abolitionist, social activist, poet Julia Ward Howe (1850),[104] and Benedictine monk and historian Cuthbert Butler (1898).[105]

During the 19th century numerous monarchs visited San Lazzaro, including Prince Napoléon Bonaparte,[104] Ludwig I of Bavaria (1841),[106] Margherita of Savoy,[107] Maximilian I of Mexico,[107] Carlota of Mexico,[107] Edward VII, Prince of Wales and future King of the United Kingdom (1861),[107] Napoleon III (1862),[107] Pedro II of Brazil (1871),[107] Princess Louise, Duchess of Argyll (1881),[107] also U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant (1878)[108] and British Prime Minister William Gladstone (1879).[109]

The Russian-Armenian marine painter Ivan Aivazovsky visited San Lazzaro in 1840. He met his older brother, Gabriel, who was working at the monastery at that time. At the monastery library and the art gallery, Aivazovsky familiarized himself with Armenian manuscripts and Armenian art in general.[110] Another Armenian painter, Vardges Sureniants, visited San Lazzaro in 1881 and researched Armenian miniatures.[111]

The musicologist Komitas lectured on Armenian folk and sacred music and researched the Armenian music notation (khaz) system in the monastery library in July 1907.[62]

The future Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin, a revolutionary at the time, found a lodging at the monastery and worked there as a bell-ringer during his 1907 trip through Italy to Switzerland to visit Vladimir Lenin, possibly in preparation to 1907 Tiflis bank robbery.[112][113]

The first meeting of the renowned Armenian poets Yeghishe Charents and Avetik Isahakyan took place in San Lazzaro in 1924.[114]

The famed Soviet Armenian composer Aram Khachaturian visited in 1963,[115] and the Soviet Armenian astrophysicist Victor Ambartsumian in 1969.[116]

In recent years, presidents of Armenia Robert Kocharyan (2005)[117] and Serzh Sargsyan (2011),[118] and Catholicos Karekin II, supreme head of the Armenian Apostolic Church (2008)[119] have visited the island.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to San Lazzaro degli Armeni (Venice). |

References

- Notes

- ↑ "Today, just 12 vardapets (learned monks) and five novices remain..."[2]

- ↑ Also romanized Surb Łazar. Usually referred to as Վենետիկի Սուրբ Ղազար կղզի, Eastern Armenian: Venetiki Surb Ghazar k(ə)ghzi, Western Armenian: Venedigi Surp Ghazar g(ə)ghzi which literally translates to "Saint Lazarus island of Venice".

- ↑ Armenian: Մխիթարեան Մայրավանք Սուրբ Ղազար, Mkhitarian Mayravank' Surb Ghazar; Italian: Monastero Mechitarista di San Lazzaro degli Armeni[5]

- ↑ A 19th-century Italian dictionary described the campanile as Oriental.[33]

- ↑ According to an 1836 source the library had 10,000 books and 400 (mostly Armenian) manuscripts.[40]

- ↑ [59][60] Catholicos Karekin II, the head of the Armenian Apostolic Church, said during his 2008 to the island that San Lazzaro is "a little Armenia thousands of kilometers away from Armenia."[61]

- Citations

- 1 2 3 4 Luther, Helmut (12 June 2011). "Venedigs Klosterinsel [Venice's monastic island]". Die Welt (in German).

- 1 2 3 4 5 Levonian Cole, Teresa (31 July 2015). "San Lazzaro degli Armeni: A slice of Armenia in Venice". The Independent.

- ↑ Valcanover, Francesco (1965). "Collection of the Armenian Mekhitarist Fathers, Island of St. Lazarus of the Armenians". Museums and Galleries of Venice. Milan: Moneta Editore. p. 149.

- ↑ "Island of Saint Lazarus of the Armenians". Michelin Guide.

- ↑ "Monastero Mechitarista di San Lazzaro degli Armeni". veneziasi.it (in Italian).

- ↑ Doody, Margaret (2007). Tropic of Venice. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 272. ISBN 978-0-8122-3984-3.

- ↑ Murphy, Christopher (2011). Shadows of Forever: The Annals of Forever. Trafford Publishing. p. 311. ISBN 9781426946011.

...had transformed San Lazzaro into a world-renowned center of Armenian culture and learning.

- ↑ Dursteler, Eric R. (2013). A Companion to Venetian History, 1400-1797. BRILL. p. 459. ISBN 9004252517.

...the island of San Lazzaro on which he established a monastery that became a center for Armenian studies and led to a revival of Armenian consciousness.

- ↑ Bakalian, Anny (1993). Armenian Americans: From Being to Feeling Armenian. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Publishers. pp. 345–346. ISBN 1-56000-025-2.

- 1 2 "Ազգինը՝ ազգին, Հռոմինը՝ Հռոմին". 168.am (168 Hours Online) (in Armenian). 26 August 2007.

Կղզի ամեն տարի այցելում է մոտ 40.000 զբոսաշրջիկ:

- ↑ Antonio Visentini (Venice 1688- Venice 1782). "Vignette of the Isola di S. Lazzaro degli Armeni". Royal Collection.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Bambakian, Vartuhi. "The Island of San Lazzaro". mechitar.com. The Armenian Mekhitarist Congregation. Archived from the original on 21 January 2015.

- 1 2 Langlois 1874, pp. 12-13.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Սուրբ Ղազար [Surb Ghazar]". Soviet Armenian Encyclopedia Volume 11 (in Armenian). Yerevan: Armenian Encyclopedia. 1985. pp. 203–204.

- ↑ Yriarte 1880, p. 302.

- 1 2 3 Adalian, Rouben Paul (2010). Historical Dictionary of Armenia. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. pp. 426–427. ISBN 978-0-8108-7450-3.

- 1 2 Langlois 1874, p. 20.

- ↑ Langlois 1874, p. 13.

- ↑ Langlois 1874, p. 21.

- ↑ Langlois 1874, p. 23.

- ↑ Langlois 1874, p. 24.

- 1 2 3 "From the Fall of the Venetian Republic to the Napoleonic Decree Recognizing the Congregation". mechitar.com. The Armenian Mekhitarist Congregation. Archived from the original on 27 February 2015.

- ↑ von Voss, Huberta, ed. (2007). Portraits of Hope: Armenians in the Contemporary World (1st English ed.). New York: Berghahn Books. p. 137. ISBN 9781845452575.

- ↑ Buckley, Jonathan (2010). The Rough Guide to Venice & the Veneto (8th ed.). London: Rough Guides. p. 226. ISBN 9781848368705.

- ↑ "Le comunita' religiose nelle isole (Religious communities in the islands)". turismo.provincia.venezia.it (in Italian). Città metropolitana di Venezia.

Pur trattandosi di una comunità religiosa, questa non venne soppressa da Napoleone che la considerò un’accademia letteraria probabilmente in rapporto all’importante attività editoriale svolta dai monaci.

- ↑ Keates, Jonathan (2005). The Siege Of Venice. Chatto & Windus. p. 411.

- ↑ Howells, William Dean (1907) [1866]. Venetian Life. Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin & Company. p. 180.

- ↑ Shcherbakova, Vera (20 November 2014). "Таинственный "остров армян" [Mysterious "island of Armenians"]". Chastny Korrespondent (in Russian). via euromag.ru.

...на данный момент кельи занимают 24 армянских монаха, приехавших на Сан-Ладзаро из разных уголков мира, где есть армянская община.

- ↑ Imboden, Durant. "San Lazzaro degli Armeni". Europe for Visitors. Archived from the original on 24 May 2014.

Its residents include 10 monks, 10 seminarians, and 15 Armenian students...

- 1 2 "The Island of San Lazzaro degli Armeni where the roses are red…and sweet". The Venice Times. 4 January 2014.

- 1 2 3 Toth, Susan Allen (19 April 1998). "Hidden Venice". Los Angeles Times. p. 3.

- ↑ Belford, Ros; Dunford, Martin; Woolfrey, Celia (2003). Italy. Rough Guides. p. 332.

- ↑ Dizionario corografico dell'Italia [Chorographic dictionary of Italy] (in Italian). Milan: Vallardi. 1869. p. 1249.

Stabilitovisi il Mechitar, rifece costui chiesa e convento e inalzò il campanile, la cui cima rivela il gusto orientale.

- ↑ "Memorial on Saint Lazarus Island, Venice, Italy". Armenian National Institute.

- ↑ Macfarlane, Charles (1830). The Armenians: A Tale of Constantinople, Volume 1. Philadelphia: Carey and Lea. p. 254.

San Lazaro is about the middle size, and adorned with a pretty garden...

- 1 2 Garrett, Martin (2001). Venice: A Cultural and Literary Companion. New York: Interlink Books. p. 166.

- 1 2 3 Carswell, John (2001). Kahn, Robert, ed. Florence, Venice & the Towns of Italy. New York Review of Books. p. 143.

- ↑ Robertson, Alexander (1905). The Roman Catholic Church in Italy. Morgan and Scott. p. 186.

- ↑ Venice: Past and Present. London: Religious Tract Society. 1853. p. 168.

- ↑ Valery, M. (1836). "Italy and the Italians". The Foreign Quarterly Review. London: Adolphus Richter & Co. 13 (32): 269.

The island of San Lazzaro, inhabited by the Armenian monks, and which is at the same time a monastery, a college, a library, and a printing establishment, deserves especial notice. The library contains 10,000 volumes, and 400 MSS. chiefly Armenian.

- ↑ Mayes, Frances (23 December 2015). "The Enduring Mystique of the Venetian Lagoon". Smithsonian.

What the monastery is most known for is the library of glass-fronted cases holding some of the monks’ 150,000 volumes...

- ↑ Dunglas, Dominique (20 April 2011). "La possibilité des îles". Le Point (in French).

San Lazzaro degli Armeni. La bibliothèque du monastère, où vivent une poignée de moines arméniens, ne compte pas moins de 200 000 livres précieux...

- 1 2 3 4 Coulie, Bernard (2014). "Collections and Catalogues of Armenian Manuscripts". In Calzolari, Valentina. Armenian Philology in the Modern Era: From Manuscript to Digital Text. Brill Publishers. pp. 23–26. ISBN 9789004259942.

- 1 2 Fodor's Venice & the Venetian Arc. Fodor's Travel Publications. 2006. p. 68.

- ↑ "Mesrop Mashtots Matenadaran". armenianheritage.org. Armenian Monuments Awareness Project.

- 1 2 Mesrobian 1973, p. 33.

- ↑ Trvnats, Anush (28 April 2012). "Թուեր Եւ Փաստեր` Հայ Գրատպութեան Պատմութիւնից". Aztag (in Armenian).

«Ուրբաթագրքի» առաջին հրատարակութիւնից աշխարհում պահպանուել է 10 օրինակ

- ↑ Yapoudjian, Hagop (14 October 2013). "Մտորումներ Սուրբ Ղազար Այցելութեան Մը Առիթով". Aztag (in Armenian).

- ↑ Ghazaryan, Davit (2014). "Կիպրիանոս հայրապետը և Հուստիանե կույսը 15-16-րդ դարերի ժապավենաձև հմայիլների գեղարվեստական հարդարանքում" (PDF). Banber Matenadarani (in Armenian): 244. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 27, 2015.

- ↑ "Guided visits to Isola di San Lazzaro degli Armeni". Città di Venezia.

- ↑ "Venise insolite: La flamme arménienne au cœur de la lagune" (in French). Radio France Internationale. 7 May 2010.

- ↑ Huchet, Jean-Bernard (2010). "Archaeoentomological study of the insect remains found within the mummy of Namenkhet Amun (San Lazzaro Armenian Monastery, Venice/Italy)" (PDF). Advances in Egyptology. Armenian Egyptology Centre (1): 59–80.

- ↑ Kalfayan, Armen (1935). "Armenian Literature, Past and Present". Books Abroad. 9 (1): 13. JSTOR 40075947.

The Monastery of the St. Lazarus Island near Venice (Lord Byron stopped there on his way to Greece and the Fathers taught him some Armenian) has long been a veritable beehive of Armenian literary activity.

- 1 2 Mathews, Jr., Edward G. (2000). "Armenia". In Johnston, Will M. Encyclopedia of Monasticism: A-L. Chicago and London: Fitzroy Dearborn. pp. 86–87.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the monastery in Venice produced hundreds of editions of Armenian texts, a number of important studies, and a dictionary of classical Armenian that is still unsurpassed.

- ↑ Conway Morris, Roderick (24 February 2012). "The Key to Armenia's Survival". The New York Times.

- ↑ Mouradyan, Anahit (2012). "Հայ տպագրության 500-ամյակը [The 500th Anniversary of the Armenian Book-Printing]". Patma-Banasirakan Handes (in Armenian) (1): 58–59.

- 1 2 3 Colgan, Nathaniel (1878). "Notes on North Italy. IV: Venice". The Irish Monthly. Irish Jesuit Province. 6: 449–450.

- 1 2 "Սբ. Ղազար կղզին գիշերով (1892)" (in Armenian). National Gallery of Armenia.

- ↑ "5th Annual Conference of the Forum of Armenian Associations of Europe Venice, Italy". faaeurope.ofirme.sk. Forum of Armenian Associations of Europe. 6–9 June 2003.

The city, which covers more than 200 islands, has a little Armenia in it; Armenian cultural and educational center Saint Ghazar

- ↑ Hamalian, Leo (1980). As others see us: the Armenian image in literature. New York: Ararat Press. p. 71.

...the Abbot Peter Mekhitar, who founded "a little Armenia with Venetian overtones...

- ↑ "Ն.Ս.Օ.Տ.Տ. Գարեգին Բ Ամենայն Հայոց Կաթողիկոսի խոսքը Մխիթարյան միաբանությանը Սուրբ Ղազար կղզում" (PDF). Etchmiadzin (in Armenian). Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin (5): 28. May 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 21, 2015.

Սուրբ Ղազարը Հայաստանից հազարավոր կիլոմետրեր հեռու մի փոքր Հայաստան է

- 1 2 Soulahian Kuyumjian, Rita (2001). Archeology of Madness: Komitas, Portrait of an Armenian Icon. Princeton, New Jersey: Gomidas Institute. p. 59. ISBN 1-903656-10-9.

- ↑ The New York Times Current History: The European war, Volume 19 (April−May−June 1919). New York: The New York Times Company. p. 72.

- ↑ Cross, F. L.; Livingstone, E. A., eds. (2005). "Venice". The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (3 rev. ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 1699. ISBN 9780192802903.

- ↑ Bolton, H. Carrington (1896). "Armenian Folk-Lore". Journal of American Folklore. 9 (35): 293. JSTOR 534118.

- ↑ Terzian, Shelley (2014). "Central effects of religious education in Armenia from Ancient Times to Post-Soviet Armenia". In Wolhuter, Charl; de Wet, Corene. International Comparative Perspectives on Religion and Education. SUN MeDIA. p. 37.

- ↑ Yriarte 1880, p. 302.

- ↑ Miele, Matteo (16 October 2015). "L'isola degli Armeni a Venezia". il Post (in Italian).

- ↑ Hewsen, Robert H. (2001). Armenia: A Historical Atlas. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 12, 158. ISBN 0-226-33228-4.

- ↑ Օտար ջրերում հայացեալ Կղզի / Հայոց հին լույսն է քեզնով նորանում... / Հայրենիքից դուրս՝ հայրենեաց համար: "Հայերն Իտալիայում [Armenians in Italy]". italy.mfa.am (in Armenian). Embassy of Armenia to Italy.

- 1 2 "Բայրոնի այցը Մխիթարյաններին Սբ. Ղազար կղզում (1899)" (in Armenian). National Gallery of Armenia.

- ↑ Pennell, Joseph. "The Armenian convent". Library of Congress.

- ↑ "Սբ Ղազարի կղզին. Վենետիկ (1958)" (in Armenian). National Gallery of Armenia.

- ↑ Davies, Emiko (10 May 2011). "Rose petal Jam from a Venetian monastery". emikodavies.com.

- ↑ "Maggio: le rose". la Repubblica (in Italian). 11 May 2012.

Mentre di origine armena è la “vartanush”, la marmellata di rose che in Italia viene prodotta a Venezia, nell’Isola di San Lazzaro degli Armeni dai monaci Mechitaristi.

- ↑ "Isola di San Lazzaro degli Armeni" (in Italian). Italian Botanical Heritage.

Una tecnica secolare ne imprigiona i profumi nella Vartanush, la marmellata di petali di rose che, tradizionalmente, vengono colti al sorgere del sole.

- ↑ Gora, Sasha (8 March 2013). "San Lazzaro degli Armeni – Where Monks Make Rose Petal Jam in Venice, Italy". Honest Cooking.

- ↑ Utudjian, A. A. (1988). "Միքայել Չամչյան (կյանքի և գործունեության համառոտ ուրվագիծ) [Michael Chamchian (a short description of his life and activity)]". Lraber Hasarakakan Gitutyunneri (9): 71–85.

- ↑ Asmarian, H. A. (2003). "Ղևոնդ Ալիշանի ճանապարհորդական նոթերից [From Ghevond Alishan's travel notes]". Lraber Hasarakakan Gitutyunneri (in Armenian) (2): 127.

- ↑ Shtikian, S. A. (1970). "Ղևոնդ Ալիշան [Ghevond Alishan]". Patma-Banasirakan Handes (in Armenian) (2): 13.

- ↑ Mikayelyan, V. (2002). "Այվազովսկի Գաբրիել [Aivazovsky Gabriel]" (in Armenian). Yerevan State University Institute for Armenian Studies.

- ↑ Melik-Pashayan, K. (1978). "Լալայան Երվանդ [Lalayan Yervand]". Soviet Armenian Encyclopedia Volume 4 (in Armenian). p. 475.

- ↑ Moubayed, Sami (2005). Steel & silk : men and women who shaped Syria 1900-2000. Seattle, Wash: Cune. pp. 71–2. ISBN 1885942400.

- ↑ New International Encyclopedia, Volume 3. Dodd, Mead. 1914. p. 120.

- ↑ Mesrobian 1973, p. 27.

- ↑ Mesrobian 1973, p. 31.

- ↑ Elze, Karl (1872). Lord Byron, a biography, with a critical essay on his place in literature. London: J. Murray. pp. 217–218.

- 1 2 Saryan, Levon A. (July–August 2011). "A Visit to San Lazzaro: An Armenian Island in the Heart of Europe Part I, Part II, Part III". Armenian Weekly.

- ↑ Vangelista, Massimo (4 September 2013). "Lord Byron in the Armenian Monastery in Venice". byronico.com.

- 1 2 3 Deolen, A. (1919). "The Mekhitarists". The New Armenia. 11 (7): 104.

- ↑ Barker, John W. (2008). Wagner and Venice. University of Rochester Press. p. 111. ISBN 9781580462884.

- ↑ Morgan, Lady (1821). Italy. A. and W. Galignani. p. 285.

- ↑ de Musset, Alfred (1867). Oeuvres, Volume 7 (in French). Paris: Charpentier. p. 246.

Après le repas, ils montaient en gondole, et s'en allaient voguer autour de l'île des Arméniens...

- ↑ Winegarten, Renee (1978). The double life of George Sand, woman and writer: a critical biography. Basic Books. p. 134.

- ↑ Sand, George (1844). "Venise, juillet 1834.". Œuvres de George Sand: Un hiver au midi de l'Europe (in French). Paris: Perrotin. p. 95.

Nous arrivâmes à l'île de Saint-Lazare, où nous avions une visite à faire aux moines arméniens.

- ↑ Sedgwick, Catharine (1841). Letters from abroad to kindred at home. New York: Harper & Brothers. p. 111.

- ↑ Bryant, William Cullen. The letters of William Cullen Bryant (1. ed.). New York: Fordham Univ. Press. p. 293. ISBN 0823209970.

- ↑ Goodman, Susan Goodman (2001). William Dean Howells a Writer's Life. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 82. ISBN 052093024X.

- ↑ Jackson, Helen Hunt (1872). Bits of Travel. J. R. Osgood. pp. 124–30.

- ↑ Plant, Margaret (2002). Venice: fragile city 1797-1977. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press. p. 225. ISBN 0300083866.

- ↑ Fawcett, Edgar. Spring Days in Venice. The Cosmopolitan. p. 620.

- ↑ Schmitt-Garibian, Wolfgang (October 2014). "The Armenian Holdings of the Bavarian State Library" (unpublished). Third International Conference of Armenian Libraries: 3.

- ↑ Cook, Edward Tyas (1912). Homes and Haunts of John Ruskin. New York: Macmillan. pp. 111–112.

- 1 2 Howe, Julia Ward (1868). From the Oak to the Olive: A Plain Record of a Pleasant Journey. Library of Alexandria. ISBN 1465513728.

- ↑ The Downside Review, Volume 17. Downside Abbey. 1898. p. 208.

- ↑ Das Armenische Kloster auf der Insel S. Lazzaro bei Venedig (in German). Armenische Druckerei. 1864.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Issaverdenz, James (1890). The Island of San Lazzaro. Venice: Armenian typography of San Lazzaro. pp. 16–8.

- ↑ Grant, Julia Dent (1988). Simon, John Y., ed. The personal memoirs of Julia Dent Grant (Mrs. Ulysses S. Grant). Southern Illinois University Press. p. 243.

- ↑ Lucas, Edward Verrall (1914). A Wanderer in Venice. The Macmillan Company. p. 302.

- ↑ Khachatrian, Shahen. ""Поэт моря" ["The Sea Poet"]" (in Russian). Center of Spiritual Culture, Leading and National Research Samara State Aerospace University.

- ↑ Adamyan, A. (2012), Վարդգես Սուրենյանց [Vardges Sureniants] (PDF) (in Armenian), National Library of Armenia, p. 7

- ↑ "When Stalin in Venice..." (PDF). Venice Magazine: 7.

Josif Stalin, the Russian dictator, was one of the last bell-ringers of the island of San Lazzaro degli Armeni, located at the heart of the lagoon. He stowed away in the port of Odessa to escape from tsarist police and arrived in Venice in 1907.

- ↑ Salinari, Raffaele K. (2010). Stalin in Italia ovvero "Bepi del giasso" (in Italian). Bologna.

Qui forse trovò alloggio nel convento adiacente alla chiesa di San Lazzaro degli Armeni, sita su un’isoletta al largo della città.

- ↑ "Իսահակյանի և Չարենցի առաջին հանդիպումը Վենետիկում". magaghat.am (in Armenian).

Մեծատաղանդ բանաստեղծ Եղիշե Չարենցին առաջին անգամ տեսա Վենետիկում, 1924 թվականին: [...] Գնում էինք ծովափ, հետո գնում էինք Մխիթարյանների վանքը` Սուրբ Ղազար:

- ↑ "Ֆոտոալբոմ [Photo gallery]". akhic.am (in Armenian). Aram Khachaturian International Competition.

Ա.Խաչատրյանը Մխիթարյան միաբանությունում Սուրբ Ղազար կղզի 1963

- ↑ Rosino, Leonida (1988). "Encounters with Victor Ambartsumian one afternoon at the San Lazzaro Degli Armeni island at Venice". Astrophysics. 29 (1): 412–414. doi:10.1007/BF01005854.

- ↑ ՀՀ նախագահ Ռոբերտ Քոչարյանը պաշտոնական այցով կմեկնի Իտալիա (in Armenian). Armenpress. 25 January 2005.

- ↑ "President Serzh Sargsyan visited the Mkhitarian Congregation at the St. Lazarus Island in Venice". president.am. Office to the President of the Republic of Armenia. 14 December 2011.

- ↑ "Catholicos Concludes Vatican Visit". Asbarez. 13 May 2008.

Bibliography

- Langlois, Victor (1874). The Armenian Monastery of St. Lazarus-Venice. Venice: Typography of St. Lazarus.

- Mesrobian, Arpena (1973). "Lord Byron at the Armenian Monastery on San Lazzaro". The Courier. Syracuse University. 11 (1): 27–37.

- Yriarte, Charles (1880) [1877]. Venice: its history, art, industries and modern life (Venise: l'histoire, l'art, l'industrie, la ville et la vie). Sitwell, F. J. (translator). New York: Scribner and Welford. pp. 301–306.

- Issaverdenz, James (1890). The Island of San Lazzaro, Or, The Armenian Monastery Near Venice. Armenian typography of San Lazzaro.

- Gordan, Lucy (February 2012). "The Venetian Island of St. Lazarus: Where Armenian Culture Survived the Diaspora". Inside the Vatican: 38–40. PDF version

Further reading

- Maguolo, Michela; Bandera, Massimiliano (1999). San Lazzaro degli Armeni: l'isola, il monastero, il restauro (in Italian). Venezia: Marsilio. ISBN 9788831774222. OCLC 247889977.

- Bolton, Claire (1982). A visit to San Lazzaro. Oxford, England: Alembic Press. OCLC 46689623.

- Richardson, Nigel (13 February 2011). "Oasis in the bedlam of Venice". The Times. London.

- Horne, Joseph (1872). "St. Lazzaro, Venice, and its Armenian Convent". The Ladies' Repository. J.F. Wright and L. Swormstedt. 32 (10): 459.

- Hacikyan, Agop Jack; Basmajian, Gabriel; Franchuk, Edward S.; Ouzounian, Nourhan (2005). The Heritage of Armenian Literature: From the eighteenth century to modern times. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. pp. 50–55. ISBN 9780814332214.

- Pasquin Valery, Antoine Claude (1839) [1838]. Historical, literary, and artistical travels in Italy, a completer and methodical guide for travellers and artists [Voyage en Italie, guide du voyageur et de l'artiste]. Paris: Baudry. pp. 191–192.

- Fell, Cicely (31 December 2014). "Out of Armenia, Venice". BBC Radio 4.

_(5182840694)(crop).jpg)

.jpg)