San Bruno Mountain

| San Bruno Mountain | |

|---|---|

View from San Bruno Mountain State Park | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 1,319 ft (402 m) NAVD 88[1] |

| Prominence | 1,114 ft (340 m) [2] |

| Coordinates | 37°41′15″N 122°26′08″W / 37.687440278°N 122.435555036°WCoordinates: 37°41′15″N 122°26′08″W / 37.687440278°N 122.435555036°W [1] |

| Geography | |

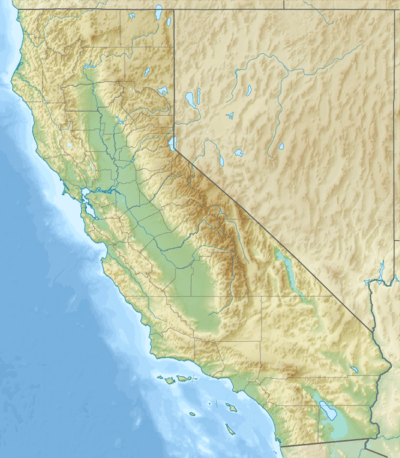

San Bruno Mountain Location of San Bruno Mountain in California | |

| Location | San Mateo County, California, U.S. |

| Parent range | Santa Cruz Mountains |

| Topo map | USGS San Francisco South |

| Climbing | |

| Easiest route | Trail hike[3] |

San Bruno Mountain is located in northern San Mateo County, California, with some slopes of the mountain crossing over into southern San Francisco. Most of the mountain lies within the 2,326-acre (941 ha) San Bruno Mountain State Park, a unique open-space island in the midst of the San Francisco Peninsula's urbanization. Next to the state park is the 83-acre (34 ha) state San Bruno Mountain Ecological Reserve on the north slope. It is near the southern boundary of San Francisco, surrounded by the cities of South San Francisco, Daly City, Colma, and Brisbane.

San Bruno Mountain is topped by a four mile long ridge. Trails to the summit afford expansive views of the San Francisco Bay Area. Radio Peak (elevation 1,319 feet or 402 metres)[1] is the highest point, hosting several radio broadcast towers, KTSF television, ION's KKPX television and NBC's KNTV Television, serving a huge area that would otherwise have poor service in the hilly Bay Area region.

The mountain provides habitat for several species of rare and endangered plants and butterflies. The endangered San Bruno elfin butterfly inhabits this mountain and a few other locations. The distinct Franciscan fog zone plants of San Bruno Mountain set it apart from other California coastal areas.[4]

Recorded history

The Portola expedition visited San Francisco Bay in 1769. The expedition is usually considered the first European presence in the area. Five years later Fernando Rivera and four soldiers climbed the mountain and watched sunrise across the bay. The mountain was named by Bruno de Heceta for his patron saint.

San Bruno Mountain consists of portions of five Mexican land grants; the southernmost being Rancho Buri Buri. Jose Antonio Sanchez, who rode by mule as a child from Sonora, Mexico was given Rancho Buri Buri in 1827, with confirmation in 1835. Rancho Buri Buri extended from the bay salt flats to San Andreas Valley and from Colma to Burlingame. Rancho Canada de Guadalupe la Visitacion y Rodeo Viejo contained most of the present day San Bruno Mountain; this rancho contains the city of Brisbane, Guadalupe Valley, Crocker Industrial Park, Visitacion Valley and the old rodeo grounds by Islais Creek. In 1835 this rancho was granted to Jacob P. Leese. In 1884 banker Charles Crocker acquired core holdings of this rancho amounting to 3,997 acres (1,618 ha) from Leese's successors, and that land devolved to the Crocker Estate Company, who are the present day owners of San Bruno Mountain. Three other ranchos held minor portions of the northern flank of San Bruno Mountain.

The cities that have grown up around the mountain are San Francisco to the north, Brisbane to the east, South San Francisco to the south and both Daly City and Colma to the west.

Nossaman attorney Robert D. Thornton pioneered the Habitat Conservation Plan (HCP) concept creating the first such plan for the area around San Bruno Mountain.

KRON (Channel 4) was the first television station to place a transmitter tower on Radio Peak, in 1949, followed by KQED and KTVU, though these tenants moved their transmitters to Sutro Tower in the 1970s. A number of FM stations built transmitter towers on the mountain, and in 2005, KNTV moved its transmitter to the mountain, on the former KCSM-TV tower. KTSF occupies the former KRON site.

Westbay Controversy

In 1965, Westbay Community Associates announced a plan to level a portion of the mountain to fill 27 square miles (70 km2) of San Francisco Bay north of Sierra Point with landfill. The proposal intended to create housing developments in the "Saddle" just north of Guadalupe Canyon Road and in the landfill zone.

In order to remove 250 million cubic yards (190,000,000 m3) of earth from the ridge, Westbay proposed using a conveyor belt system to transport the fill across Bayshore Boulevard and Bayshore Freeway to offshore barges, which would then deposit the material along the shores of the Bay.[5]

Opposition by organizations such as Save The Bay[6] and the residents of Brisbane led to the defeat of Westbay's conveyor plan in June 1967 and the ceasing of all landfill operations at Sierra Point by December 1972.[5]

Terra Bay Development

.jpg)

The Terra Bay project was approved in the mid-1980s for development at the south and southeast base of San Bruno Mountain.[7] Terra Bay was constructed in three phases: the first phase constructed townhomes and detached houses; the second phase constructed more housing units, including the one of the tallest buildings in South San Francisco,[8] a condominium tower named the Peninsula Mandalay, and the third phase constructed an office building named Centennial Towers.[9] The original developer, W.W. Dean & Associates, was unable to complete the project, and SunChase Holdings acquired the project in 1992, completing site preparation before selling the parcels for Phase I to Centex Homes.[10]

The Terra Bay site was known to include habitat for the Mission blue and Callippe silverspot butterflies; the original developer received a US$15,000 (equivalent to $36,000 in 2015) fine in 1983 for bulldozing part of the habitat during site preparation.[11] Under the terms established by the 1982 amendment to the Endangered Species Act, the nation's first-ever Habitat Conservation Plan (HCP) was agreed upon, allowing developers to destroy the habitat of endangered species if substitute lands were made available.[12] SunChase agreed to fund ecological restoration to mitigate the impact of Terra Bay during the development of Phase I under the terms of the San Bruno HCP.[13] SunChase entered a joint venture with Myers Development for the development of Phases II and III;[10] although Phase III had 20 acres (8.1 ha) of land available for construction, the completed Centennial Towers was scaled back to fit on just 8 acres (3.2 ha),[14] partly in order to establish a buffer zone between the development and an ancient shellmound.

.jpg)

Although the shellmound had been noted as early as 1909,[15] a sample of 22 cubic metres (780 cu ft) of the shellmound conducted in 1989 by Holman & Associates (commissioned by W.W. Dean) revealed the massive shellmound contained human remains, and further, that the shellmound site is eligible for nomination to the National Register of Historic Places.[16] The Holman & Associates report was not made public for nearly ten years,[17] with leaked copies circulating privately in 1997, and a public copy incorporated in the draft Environmental Impact Report in 1998.[16] A lawsuit was settled out of court, resulting in the developer selling the land which included the shellmound and habitat for the Mission blue and Callippe silverspot butterflies to The Trust for Public Land,[18] who would incorporate the parcel into San Bruno Mountain State Park. Ultimately, Terra Bay Phase III was scaled back significantly from the original mixed-use retail/office proposal.[19][20] The shorter 12-story south tower was completed in 2009,[21][22] and the taller 21-story north tower is scheduled for completion at the end of 2016.[23]

Topography, geology and climate

The name "San Bruno Mountains" was first affixed by the Geological Survey of California in 1865, describing the place as a short range extending from Sierra Point nearly to the Pacific Ocean. The mountain itself actually consists of two parallel northwest trending ranges separated by the Guadalupe Valley. These two ranges are united by a saddle at the northern end of Colma Canyon. The northernmost range attains a peak of 850 feet (259 m), while the southern range rises abruptly from Merced Valley at the south to reach Radio peak in a horizontal distance of only 0.8 miles (1.3 km). This southern range is often referred to as San Bruno Mountain., while the northern range is called the Crocker Hills.

The region is drained by two major streams: Guadalupe Valley Creek flowing through Guadalupe Valley, and Colma Creek from a source in the Flower Garden into the deep cleft of Colma Canyon and thence into Merced Valley.

In the 1850s San Francisco Bay lapped against the eastern sandstone cliff flank of San Bruno Mountain, whereas today the entire shoreline is bay fill.

These two mountains are underlain primarily with late Cretaceous dark greenish-gray graywacke, a poorly sorted sandstone containing angular rock fragments, about ten percent feldspar and detrital chert. The angular unsorted content implies a rapid erosion and burial in a depositional basin, with an outcome of few fossils. Exposed graywacke can be observed on high ridges and on the steep canyon walls. Radiolarian chert is exposed on certain south facing slopes of San Bruno Mountain and at Point San Bruno.

.jpg)

The most important rock type is serpentine, a greenish soft material that is the California State Rock. Outcrops of this rock are found near Serbian Ravine and at Point San Bruno. Serpentine's importance is its unusual and diverse mineral composition which imparts to associate soils the ability to host rare plants, not usually supported on common soils. Therefore, San Bruno Mountain is a habitat for a variety of uncommon plants, which in turn host even rarer animal life.

Since the climate is dominated by marine air flow, temperatures are milder in the winter and summer on these mountains. Furthermore, summer temperatures are further reduced by the annual appearance of marine fog enshrouding the mountains most mornings between late June and late August; this fog is particularly pronounced on the western slopes. Minimum credible temperature might extend as low as 20 °F (−7 °C) in the sheltered valleys. Winds are higher than on reference locations at surrounding points; in fact, on ridges it is not uncommon for the most fierce winter storms to produce gusts from 50 to 80 miles per hour (80 to 129 km/h). Precipitation is similar to surrounding cities, or about 22 inches (560 mm) per-annum, with approximately 66 days-per-annum realizing perceptible rain. On several occasions the mountain has been temporarily covered by snow, including December 1932, January 1952, January 1957, January 1962, and February 1976.

Vegetation

There are a variety of habitats in this mountainous area, and notably the following rare or endangered flora:

- Coast rock cress (Arabis blepharophylla)

- Franciscan Wallflower (Erysimum franciscanum)

- Montara Manzanita (Arctostaphylos montaraensis)

- Pacifica Manzanita (Arctostaphylos pacifica)

- San Bruno Mountain Manzanita (Arctostaphylos imbricata)

- San Francisco Campion (Silene verecunda)

- San Francisco Owl's Clover (Orthocarpus floribundus)

See also

- San Bruno Mountain State Park

- Mission blue butterfly

- Mission blue butterfly habitat conservation

- San Bruno elfin butterfly

- List of summits of the San Francisco Bay Area

- List of California state parks

References

- 1 2 3 "San Bruno Mountain Reset". NGS data sheet. U.S. National Geodetic Survey. Retrieved 2009-06-24.

- ↑ "San Bruno Mountain, California". Peakbagger.com. Retrieved 2009-08-24.

- ↑ "San Bruno Mountain Summit Loop". Trailspotting. Retrieved 2009-08-24.

- ↑ California Department of Fish and Game's website, San Bruno Ecological Reserve.

- 1 2 "Birsbane: City of Stars, The First Twenty-Five Years (1961-1986)" (PDF). The City of Brisbane. 1989. Archived from the original on 2015-09-25. Retrieved 2015-09-25.

- ↑ Taugher, Mike (2011-11-05). "A pioneer remembers how she and friends saved the bay". Contra Costa Times. Archived from the original on 2012-01-16. Retrieved 2012-01-10.

- ↑ Wildermuth, John (18 November 1995). "South S.F. to Get New Homes / Terrabay project resumes after lengthy delays". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ↑ The Peninsula Mandalay at Emporis

- ↑ Centennial Towers South at Emporis

- 1 2 "Domestic Master Planned Communities: Terra Bay; South San Francisco, CA". SunChase Holdings. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ↑ "Habitat of rare butterflies bulldozed". The Day. AP. 6 July 1983. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ↑ Feuerstein, Adam (25 April 1997). "Butterflies vs. builders: The San Bruno compromise". San Francisco Business Times. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ↑ Pimentel, Benjamin (6 December 1996). "Accord on San Bruno Mountain / Long-stalled housing venture can proceed". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ↑ "Centennial Tower". Skidmore, Owings, Merrill. 2009. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ↑ Nelson, N.C. (1909). "Shellmounds of the San Francisco Bay Region". University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology. 7 (4): 309–356. Retrieved 21 June 2016.

- 1 2 Dury, John; Townsend, Laird (2005). "Shellmound at San Bruno Mountain". FoundSF. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ↑ Andres, Fred (1 April 1998). "The Large Ohlone Shell Mound at San Bruno Mountain". Sierra Club San Francisco Bay Chapter GLS. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ↑ Buchanan, Wyatt (10 September 2004). "SAN BRUNO / Conservationists buy land in San Bruno". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ↑ Brown, Todd R. (15 March 2006). "Terrabay proposal comes to light". San Mateo County Times. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ↑ "Terrabay back at it with two towers in Phase III project". San Francisco Examiner. 16 August 2006. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ↑ Murtagh, Heather (30 December 2008). "Second office tower on hold". San Mateo Daily Journal. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ↑ Murtagh, Heather (11 February 2009). "Centennial Tower open for tenants". San Mateo Daily Journal. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ↑ Walsh, Austin (24 December 2015). "New developer acquires Centennial Towers project: Keystone office project purchased for conversion to R&D space in South San Francisco". San Mateo Daily Journal. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- Climate Survey of San Bruno Mountain, prepared for Crocker Land Company by Metronics Associates, Palo Alto, Ca., October 20, 1967

- Elizabeth McClintock and Walter Knight, A Flora of the San Bruno Mountains, San Mateo County, California, Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences, Fourth Series, Volume XXXII, no. 20, pp. 587–677, November 29, 1968

- J.D. Whitney, Geological Survey of California (1865)

- John Hunter Thomas, A Flora of the Santa Cruz Mountains (1960)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to San Bruno Mountain. |

- "San Bruno Mountain". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 2009-08-24.

- Environmental Services Agency of San Mateo County, information on history, trails, park map, activities, park hours.

- San Bruno Mountain State Park

- San Bruno Mountain Watch, whose mission is to preserve San Bruno Mountain's Native American village sites and endangered habitats.

- Trailspotting: Hiking the San Bruno Mountain Summit Loop Trail Description, Photos and GPS/mapping data