Salmonellosis

| Salmonellosis | |

|---|---|

| |

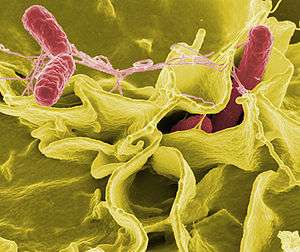

| Electron micrograph showing Salmonella typhimurium (red) invading cultured human cells | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| ICD-10 | A02.0 |

| ICD-9-CM | 003.0 |

| DiseasesDB | 11765 |

| MedlinePlus | 000294 |

Salmonellosis is an infection caused by Salmonella bacteria. Most people infected with Salmonella develop diarrhea, fever, vomiting, and abdominal cramps 12 to 72 hours after infection. In most cases, the illness lasts four to seven days, and most people recover without treatment.[1] In some cases, the diarrhea may be so severe that the patient becomes dangerously dehydrated and must be hospitalized.

Intravenous fluids may be used to treat dehydration. Medications may be used to provide symptomatic relief, such as fever reduction. In severe cases, the Salmonella infection may spread from the intestines to the blood stream, and then to other body sites; this is known as typhoid fever and is treated with antibiotics.

The elderly, infants, and those with impaired immune systems are more likely to develop severe illness. Some people afflicted with salmonellosis later experience reactive arthritis, which can have long-lasting, disabling effects. The only two species of Salmonella are Salmonella bongori and Salmonella enterica. The latter is divided in six subspecies: S. e. enterica, S. e. salamae, S. e. arizonae, S. e. diazonae, S. e. houtenase, and S. e. indica. These subspecies are further divided into numerous serovars. Because the serovars only differ in serotypes, and therefore in infection potential, the serovars are not italicised and are written with a capital letter as they still belong to the same subspecies.

The species Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica contains over 60% of the total number of serovars and 99% of the serovars that are capable of infecting cold- and warm-blooded animals, as well as humans. Infections are usually contracted from sources such as:

- Poultry, pork, beef, and fish (seafood), if the meat is prepared incorrectly or is infected with the bacteria after preparation[2]

- Infected eggs, egg products, and milk when not prepared, handled, or refrigerated properly[2]

- Tainted fruits and vegetables[2]

Reptiles such as red-eared slider turtles and green iguanas may carry Salmonella bongori (which inhabits cold-blooded animals) in their intestines which can cause intestinal infections. The most severe human Salmonella infection is caused by S. enterica subsp. enterica ser. typhi which leads to typhoid fever, an infection that often proves fatal if not treated with the appropriate antibiotics. This serovar is restricted to humans and is usually contracted through direct contact with the fecal matter of an infected person. Typhoid fever is endemic in the developing world, where unsanitary conditions are more likely to prevail, and which can affect as many as 21.5 million people each year. Recorded cases of typhoid fever in the developed world are mostly related to recent travel in areas where Salmonella typhi is endemic.

Signs and symptoms

Enteritis

After a short incubation period of a few hours to one day, the bacteria multiply in the intestinal lumen, causing an intestinal inflammation. Most people with salmonellosis develop diarrhea, fever, vomiting, and abdominal cramps 12 to 72 hours after infection.[3] Diarrhea is often mucopurulent (containing mucus or pus) and bloody. In most cases, the illness lasts four to seven days, and most people recover without treatment. In some cases, though, the diarrhea may be so severe that the patient becomes dangerously dehydrated and must be taken to a hospital. At the hospital, the patient may receive intravenous fluids to treat the dehydration, and may be given medications to provide symptomatic relief, such as fever reduction. In severe cases, the Salmonella infection may spread from the intestines to the blood stream, and then to other body sites, and can cause death, unless the person is treated promptly with antibiotics.

In otherwise healthy adults, the symptoms can be mild. Normally, no sepsis occurs, but it can occur exceptionally as a complication in the immunocompromised. However, in people at risk such as infants, small children, and the elderly, Salmonella infections can become very serious, leading to complications. In infants, dehydration can cause a state of severe toxicity. Extraintestinal localizations are possible, especially Salmonella meningitis in children, osteitis, etc. Children with sickle-cell anemia who are infected with Salmonella may develop osteomyelitis. Treatment of osteomyelitis, in this case, will be to use fluoroquinolones (ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, etc., and nalidixic acid).

Those whose only symptom is diarrhea usually completely recover, but their bowel habits may not return to normal for several months.[4]

Typhoid fever

Typhoid fever occurs when Salmonella bacteria enter the lymphatic system and cause a systemic form of salmonellosis. Endotoxins first act on the vascular and nervous apparatus, resulting in increased permeability and decreased tone of the vessels, upset thermal regulation, vomiting, and diarrhea. In severe forms of the disease, enough liquid and electrolytes are lost to upset the water-salt metabolism, decrease the circulating blood volume and arterial pressure, and cause hypovolemic shock. Septic shock may also develop. Shock of mixed character (with signs of both hypovolemic and septic shock) are more common in severe salmonellosis. Oliguria and azotemia develop in severe cases as a result of renal involvement due to hypoxia and toxemia.[3]

Long-term

Salmonellosis is associated with later irritable bowel syndrome[5] and inflammatory bowel disease.[6] Evidence however does not support it being a direct cause of the latter.[6]

A small number of people afflicted with salmonellosis experience reactive arthritis, which can last months or years and can lead to chronic arthritis.[7][8] In sickle-cell anemia, osteomyelitis due to Salmonella infection is much more common than in the general population. Though Salmonella infection is frequently the cause of osteomyelitis in sickle-cell anemia patients, it is not the most common cause, which remains to be Staphylococcus infection.

Those infected may become asymptomatic carriers, but it is relatively uncommon, with shedding observed in only 0.2 to 0.6% of cases after a year.[9]

Causes

- Contaminated food, often having no unusual look or smell

- Poor kitchen hygiene, especially problematic in institutional kitchens and restaurants because this can lead to a significant outbreak

- Excretions from either sick or infected but apparently clinically healthy people and animals (especially dangerous are caregivers and animals)

- Polluted surface water and standing water (such as in shower hoses or unused water dispensers)

- Unhygienically thawed poultry (the meltwater contains many bacteria)

- An association with reptiles (pet tortoises, snakes, iguanas,[10][11] and aquatic turtles) is well described.[12]

- Amphibians such as frogs

Salmonella bacteria can survive for some time without a host; thus, they are frequently found in polluted water, with contamination from the excrement of carrier animals being particularly important.

The European Food Safety Authority highly recommends that when handling raw turkey meat, consumers and people involved in the food supply chain should pay attention to personal and food hygiene.[13]

An estimated 142,000 Americans are infected each year with Salmonella Enteritidis from chicken eggs,[14] and about 30 die.[15] The shell of the egg may be contaminated with Salmonella by feces or environment, or its interior (yolk) may be contaminated by penetration of the bacteria through the porous shell or from a hen whose infected ovaries contaminate the egg during egg formation.[16][17]

Nevertheless, such interior egg yolk contamination is theoretically unlikely.[18][19][20][21] Even under natural conditions, the rate of infection was very small (0.6% in a study of naturally contaminated eggs[22] and 3.0% among artificially and heavily infected hens[23]).

Prevention

The FDA has published guidelines[24] to help reduce the chance of food-borne salmonellosis. Food must be cooked to 68–72°C (145–160°F), and liquids such as soups or gravies must be boiled. Freezing kills some Salmonella, but it is not sufficient to reliably reduce them below infectious levels. While Salmonella is usually heat-sensitive, it does acquire heat resistance in high-fat environments such as peanut butter.[25]

Vaccine

Antibodies against nontyphoidal Salmonella were first found in Malawi children in research published in 2008. The Malawian researchers have identified an antibody that protects children against bacterial infections of the blood caused by nontyphoidal Salmonella. A study at Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Blantyre found that children up to two years old develop antibodies that aid in killing the bacteria. This could lead to a possible Salmonella vaccine for humans.[26]

A recent study has tested a vaccine on chickens which offered efficient protection against salmonellosis.[27]

Vaccination of chickens against Salmonella essentially wiped out the disease in the United Kingdom. A similar approach has been considered in the United States, but the Food and Drug Administration decided not to mandate vaccination of hens.[28]

Industrial hygiene

Since 2011, Denmark has had zero cases of human salmonella poisoning.[29] The country eradicated salmonella without vaccines and antibiotics by focusing on eliminating the infection from "breeder stocks", implementing various measures to prevent infection, and taking a zero-tolerance policy towards salmonella in chickens.[29]

Treatment

Electrolytes may be replenished with oral rehydration supplements (typically containing salts sodium chloride and potassium chloride).

Appropriate antibiotics, such as ceftriaxone, may be given to kill the bacteria but are not necessary in most cases.[9] Azithromycin has been suggested to be better at treating typhoid in resistant populations than both fluoroquinolone drugs and ceftriaxone. Antibiotic resistance rates are increasing throughout the world, so health care providers should check current recommendations before choosing an antibiotic.

Epidemiology

In the mid- to late 20th century, Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis was a common contaminant of eggs. Depending on the region, this is less common now with the advent of hygiene measures in egg production, and the vaccination of laying hens to prevent Salmonella colonization. Various Salmonella serovars (strains) also cause severe diseases in animals.

United States

About 142,000 people in the United States are infected each year with Salmonella Enteritidis from chicken eggs, and about 30 die.[15]

In 2010, an analysis of death certificates in the United States identified a total of 1,316 Salmonella-related deaths from 1990 to 2006. These were predominantly among older adults and those who were immunocompromised.[30] The U.S. government reported as many as 20% of all chickens were contaminated with Salmonella in the late 1990s, and 16.3% were contaminated in 2005.[31]

The United States has struggled to control salmonella infections, with the rate of infection rising from 2001 to 2011. In 1998, the USDA moved to close plants if salmonella was found in excess of 20 percent, which was the industry’s average at the time, for three consecutive tests.[32] Texas-based Supreme Beef Processors, Inc. sued on the argument that Salmonella is naturally occurring and ultimately prevailed when a federal appeals court affirmed a lower court.[32] These issues were highlighted in a proposed Kevin's Law (formally proposed as the Meat and Poultry Pathogen Reduction and Enforcement Act of 2003), of which components were included the Food Safety Modernization Act passed in 2011, but that law applies only to the FDA and not the USDA.[32] The USDA proposed a regulatory initiative in 2011 to Office of Management and Budget.[33]

Europe

Since July 2012, an outbreak of salmonellosis occurred in Northern Europe caused by Salmonella thompson. The infections were linked to smoked salmon from the manufacturer Foppen, where the contamination had occurred. Most infections were reported in the Netherlands, over 1060 infections with this subspecies have been confirmed, as well as four mortalities.[34][35]

A case of widespread infection was detected mid-2012 in seven EU countries. Over 400 people had been infected with Salmonella enterica serovar Stanley (S. Stanley) that usually appears in the regions of Southeast Asia. After several DNA analyses seemed to point to a specific Belgian strain, the "Joint ECDC/E FSA Rapid Risk Assessment" report detected turkey production as the source of infection.[36]

In Germany, food poisoning infections must be reported.[37] Between 1990 and 2005, the number of officially recorded cases decreased from about 200,000 to about 50,000 cases.

Elsewhere

In March 2007, around 150 people were diagnosed with salmonellosis after eating tainted food at a governor's reception in Krasnoyarsk, Russia. Over 1,500 people attended the ball on March 1, and fell ill as a consequence of ingesting Salmonella-tainted sandwiches.

About 150 people were sickened by Salmonella-tainted chocolate cake produced by a major bakery chain in Singapore, in December 2007.

History

Both salmonellosis and the Salmonella genus of microorganisms derive their names from a modern Latin coining after Daniel E. Salmon (1850–1914), an American veterinary surgeon. He had help from Theobald Smith, and together they found the bacterium in pigs.

Four-inch regulation

The "Four-inch regulation" or "Four-inch law" is a colloquial name for a regulation issued by the U.S. FDA in 1975, restricting the sale of turtles with a carapace length less than four inches (10 cm).[38]

The regulation was introduced, according to the FDA, "because of the public health impact of turtle-associated salmonellosis." Cases had been reported of young children placing small turtles in their mouths, which led to the size-based restriction.

See also

References

- ↑ Salmonella, FoodSafety.gov

- 1 2 3 "FDA/CFSAN - Food Safety A to Z Reference Guide - Salmonella". FDA - Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition. 2008-07-03. Archived from the original on January 17, 2009. Retrieved 2009-02-14.

- 1 2 Santos, Renato L.; Shuping Zhang; Renee M. Tsolis; Robert A. Kingsley; L. Gary Adams; Adreas J. Baumler (2001). "Animal models od Salmonella infections: enteritis versus typhoid fever". Microbes and Infection. 3: 1335–1344. doi:10.1016/s1286-4579(01)01495-2.

- ↑ "What is Salmonellosis?". US Center of Disease Control and Prevention.

- ↑ Smith, JL; Bayles, D (July 2007). "Postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome: a long-term consequence of bacterial gastroenteritis.". Journal of food protection. 70 (7): 1762–9. PMID 17685356.

- 1 2 Mann, EA; Saeed, SA (January 2012). "Gastrointestinal infection as a trigger for inflammatory bowel disease.". Current opinion in gastroenterology. 28 (1): 24–9. PMID 22080823.

- ↑ Leirisalo-Repo, M; P Helenius; T Hannu; A Lehtinen; J Kreula; M Taavitsainen; S Koskimies (1997). "Long term prognosis of reactive salmonella arthritis". Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 56 (9): 516–520. doi:10.1136/ard.56.9.516.

- ↑ Dworkin MS, Shoemaker PC, Goldoft MJ, Kobayashi JM (2001). "Reactive arthritis and Reiter's syndrome following an outbreak of gastroenteritis caused by Salmonella enteritidis". Clin Infect Dis. 33 (7): 1010–14. doi:10.1086/322644. PMID 11528573.

- 1 2 "Nontyphoidal Salmonella Infections". Merck Manual. Retrieved 2016-09-19.

- ↑ "Reptile-Associated Salmonellosis—Selected States, 1998–2002". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 12 December 2003. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Mermin J, Hoar B, Angulo FJ (March 1997). "Iguanas and Salmonella marina infection in children: a reflection of the increasing incidence of reptile-associated salmonellosis in the United States". Pediatrics. 99 (3): 399–402. doi:10.1542/peds.99.3.399. PMID 9041295.

- ↑ "Ongoing investigation into reptile associated salmonella infections". Health Protection Report. 3 (14). 9 April 2009. Retrieved 12 April 2009.

- ↑ "Multi-country outbreak of Salmonella Stanley infections Update". EFSA Journal. European Food Safety Authority. 21 September 2012. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2012.2893.

- ↑ "Playing It Safe With Eggs". FDA Food Facts. 2013-02-28. Retrieved 2013-03-02.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) estimates that 142,000 illnesses each year are caused by consuming eggs contaminated with Salmonella.

- 1 2 Black, Jane; O'Keefe, Ed (2009-07-08). "Administration Urged to Boost Food Safety Efforts". Washington Post. Retrieved 2009-07-07.

Among them is a final rule, issued by the FDA, to reduce the contamination in eggs. About 142,000 Americans are infected each year with Salmonella enteritidis from eggs, the result of an infected hen passing along the bacterium. About 30 die.

- ↑ Gantois, Inne; Richard Ducatelle; Frank Pasmans; Freddy Haesebrouck; Richard Gast; Tom J. Humphrey; Filip Van Immerseel (July 2009). "Mechanisms of egg contamination by Salmonella Enteritidis". FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 33 (4): 718–738. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00161.x. PMID 19207743.

Eggs can be contaminated on the outer shell surface and internally. Internal contamination can be the result of penetration through the eggshell or by direct contamination of egg contents before oviposition, originating from infection of the reproductive organs. Once inside the egg, the bacteria need to cope with antimicrobial factors in the albumen and vitelline membrane before migration to the yolk can occur

- ↑ Humphrey, T. J. (January 1994). "Contamination of egg shell and contents with Salmonella enteritidis: a review". International Journal of Food Microbiology. 21 (1–2): 31–40. doi:10.1016/0168-1605(94)90197-X. PMID 8155476. Retrieved 2010-08-19.

Salmonella enteritidis can contaminate the contents of clean, intact shell eggs as a result of infections of the reproductive tissue of laying hens. The principal site of infection appears to be the upper oviduct. In egg contents, the most important contamination sites are the outside of the vitelline membrane or the albumen surrounding it. In fresh eggs, only a few salmonellae are present. As albumen is an iron-restricted environment, growth only occurs with storage-related changes to vitelline membrane permeability, which allows salmonellae to invade yolk contents.

- ↑ Stokes, J.L.; W.W. Osborne; H.G. Bayne (September 1956). "Penetration and Growth of Salmonella in Shell Eggs". Journal of Food Science. 21 (5): 510–518. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2621.1956.tb16950.x.

Normally, the oviduct of the hen is sterile and therefore the shell and internal contents of the egg are also free of microorganisms (10,16). In some instances, however, the ovaries and oviduct may be infected with Salmonella and these may be deposited inside the egg (12). More frequently, however, the egg becomes contaminated after it is laid.

- ↑ Okamura, Masashi; Yuka Kamijima; Tadashi Miyamoto; Hiroyuki Tani; Kazumi Sasai; Eiichiroh Baba (2001). "Differences Among Six Salmonella Serovars in Abilities to Colonize Reproductive Organs and to Contaminate Egges in Laying Hens". Avian Diseases. 45 (1): 61–69. doi:10.2307/1593012. JSTOR 1593012. PMID 11332500.

when hens were artificially infected to test for transmission rate to yolks: "Mature laying hens were inoculated intravenously with 106 colony-forming units of Salmonella enteritidis, Salmonella typhimurium, Salmonella infantis, Salmonella hadar, Salmonella heidelberg, or Salmonella montevideo to cause the systemic infection. Salmonella Enteritidis was recovered from three yolks of the laid eggs (7.0%), suggesting egg contamination from the transovarian transmission of S. enteritidis."

- ↑ Gast, RK; D.R. Jones; K.E. Anderson; R. Guraya; J. Guard; P.S. Holt (August 2010). "In vitro penetration of Salmonella enteritidis through yolk membranes of eggs from 6 genetically distinct commercial lines of laying hens". Poultry Science. 89 (8): 1732–1736. doi:10.3382/ps.2009-00440. PMID 20634530. Retrieved 2010-08-20.

In this study, egg yolks were infected at the surface of the yolk (vitelline membrane) to determine the percentage of yolk contamination (a measure used to determine egg contamination resistance, with numbers lower than 95% indicating increasing resistance): Overall, the frequency of penetration of Salmonella Enteritidis into the yolk contents of eggs from individual lines of hens ranged from 30 to 58% and the mean concentration of Salmonella Enteritidis in yolk contents after incubation ranged from 0.8 to 2.0 log10 cfu/mL.

- ↑ Jaeger, Gerald (Jul–Aug 2009). "Contamination of eggs of laying hens with S. Enteritidis". Veterinary Survey (Tierärztliche Umschau). 64 (7–8): 344–348. Retrieved 2010-08-20.

The migration of the bacterium into the nutritionally rich yolk is constrained by the lysozyme loaded vitelline membrane, and would need warm enough storage conditions within days and weeks. The high concentration on of antibodies of the yolk does not inhibit the Salmonella multiplication. Only seldom does transovarian contamination of the developing eggs with S. enteritidis make this bacterium occur in laid eggs, because of the bactericidal efficacy of the antimicrobial peptides

- ↑ Humphrey, T.J.; A. Whitehead; A. H. L. Gawler; A. Henley; B. Rowe (1991). "Numbers of Salmonella enteritidis in the contents of naturally contaminated hens' eggs". Epidemiology and Infection. 106 (3): 489–496. doi:10.1017/S0950268800067546. PMC 2271858

. PMID 2050203. Retrieved 2010-08-19.

. PMID 2050203. Retrieved 2010-08-19. Over 5700 hens eggs from 15 flocks naturally infected with Salmonella enteritidis were examined individually for the presence of the organism in either egg contents or on shells. Thirty-two eggs (0·6%) were positive in the contents. In the majority, levels of contamination were low.

- ↑ Gast, Richard; Rupa Guraya; Jean Guard; Peter Holt; Randle Moore (March 2007). "Colonization of specific regions of the reproductive tract and deposition at different locations inside eggs laid by hens infected with Salmonella Enteritidis or Salmonella Heidelberg". Journal of Avian Diseases. 51 (1): 40–44. doi:10.1637/0005-2086(2007)051[0040:cosrot]2.0.co;2. PMID 17461265. Retrieved 2010-08-20.

when hens are artificially infected with unrealistically large doses (according to the author): In the present study, groups of laying hens were experimentally infected with large oral doses of Salmonella Heidelberg, Salmonella Enteritidis phage type 13a, or Salmonella Enteritidis phage type 14b. For all of these isolates, the overall frequency of ovarian colonization (34.0%) was significantly higher than the frequency of recovery from either the upper (22.9%) or lower (18.1%) regions of the oviduct. No significant differences were observed between the frequencies of Salmonella isolation from egg yolk and albumen (4.0% and 3.3%, respectively).

- ↑ "Salmonella Questions and Answers". USDA Food Safety and Inspection Service. 2006-09-20. Retrieved 2009-01-21.

- ↑ "FDA issues peanut safety guidelines for foodmakers". Reuters. 2009-03-10.

- ↑ MacLennan CA, Gondwe EN, Msefula CL, et al. (April 2008). "The neglected role of antibody in protection against bacteremia caused by nontyphoidal strains of Salmonella in African children". J. Clin. Invest. 118 (4): 1553–62. doi:10.1172/JCI33998. PMC 2268878

. PMID 18357343.

. PMID 18357343. - ↑ Nandre, Rahul M.; Lee, John Hwa (Jan 2014). "Construction of a recombinant-attenuated Salmonella Enteritidis strain secreting Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin B subunit protein and its immunogenicity and protection efficacy against salmonellosis in chickens.". Vaccine. 32 (2): 425–431. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.10.054. PMID 24176491.

- ↑ Neuman, William (2010-08-24). "U.S. Forgoes Salmonella Vaccine for Egg Safety". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2016-03-12.

- 1 2 "Contaminated chicken: After illnesses soar, Denmark attacks salmonella at its source". Retrieved 2016-09-18.

- ↑ Cummings, PL; Sorvillo F; Kuo T (November 2010). "Salmonellosis-related mortality in the United States, 1990–2006". Foodborne pathogens and disease. 7 (11): 1393–9. doi:10.1089/fpd.2010.0588. PMID 20617938.

- ↑ Burros, Marian (March 8, 2006). "More Salmonella Is Reported in Chickens". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-05-13.

- 1 2 3 "Salmonella Lurks From Farm to Fork « News21 2011 National Project". foodsafety.news21.com. Retrieved 2016-09-18.

- ↑ "Ground Turkey Recall Shows We Still Need Kevin's Law | Food Safety News". 2011-08-12. Retrieved 2016-09-18.

- ↑ Veelgestelde vragen Salmonella Thompson 15 oktober 2012, Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu [Frequently asked questions Salmonella Thompson 15 October 2012, Netherlands Institute for Public Health and the Environment].

- ↑ "Salmonella besmetting neemt verder af, 2 november 2012, Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu" [Salmonella infections continue to decline 2 November 2012, Netherlands Institute for Public Healthand the Environment].

- ↑ Multi-country outbreak of Salmonella Stanley infections Update EFSA Journal 2012;10(9):2893 [16 pp.]. Retrieved 04/23/2013

- ↑ § 6 and § 7 of the German law on infectious disease prevention, Infektionsschutzgesetz

- ↑ "Human Health Hazards Associated with Turtles". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 2007-06-09. Retrieved 2007-06-29.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Salmonella. |

- CDC website, Division of Bacterial and Mycotic Diseases, Disease Listing: Salmonellosis

- CFIA Website: Salmonellae

- Protective salmonella antibodies found in Malawi children, Sub-Saharan Africa gateway, Science and Development Network,