Salmonella

| Salmonella | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Kingdom: | Eubacteria |

| Phylum: | Proteobacteria |

| Class: | Gammaproteobacteria |

| Order: | Enterobacteriales |

| Family: | Enterobacteriaceae |

| Genus: | Salmonella Lignieres 1900 |

| Species | |

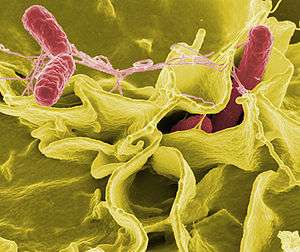

Salmonella /ˌsælməˈnɛlə/ is a genus of rod-shaped (Bacillus) Gram-negative bacteria of the Enterobacteriaceae family. The two species of Salmonella are Salmonella enterica and Salmonella bongori. Salmonella enterica is the type species and is further divided into six subspecies[1] that include over 2500 serovars.

S. enterica subspecies are found worldwide in all warm-blooded animals, and in the environment. S. bongori is restricted to cold-blooded animals, particularly reptiles.[2] Strains of Salmonella cause illnesses such as typhoid fever, paratyphoid fever, and food poisoning (salmonellosis).[3]

Traits

Salmonella species are nonspore-forming, predominantly motile enterobacteria with cell diameters between about 0.7 and 1.5 µm, lengths from 2 to 5 µm, and peritrichous flagella (all around the cell body).[4] They are chemotrophs, obtaining their energy from oxidation and reduction reactions using organic sources. They are also facultative anaerobes, capable of surviving with or without oxygen.[4]

Taxonomy

The genus Salmonella is part of the family of Enterobacteriaceae. Its taxonomy has been revised and has the potential to confuse. Two species comprise the genus, Salmonella bongori and Salmonella enterica, the latter of which is divided into six subspecies: S. e. enterica, S. e. salamae, S. e. arizonae, S. e. diarizonae, S. e. houtenae, and S. e. indica.[5][6] The taxonomic group contains more than 2500 serovars, defined on the basis of the somatic O (lipopolysaccharide) and flagellar H antigens (the Kauffman–White classification). The full name of a serovar is given as, for example, Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium, but can be abbreviated to Salmonella Typhimurium. Further differentiation of strains to assist clinicoepidemiological investigation may be achieved by antibiogram and by supra- or subgenomic techniques such as pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, multilocus sequence typing, and, increasingly, whole genome sequencing. Historically, salmonellae have been clinically categorized as invasive (typhoidal) or noninvasive (nontyphoidal salmonellae) based on host preference and disease manifestations in humans.[7]

History

Salmonella was first visualized in 1880 by Karl Eberth in the Peyer's patches and spleens of typhoid patients.[8] Four years later in 1884 Georg Theodor Gaffky was able to successfully grow the pathogen in pure culture.[9] A year after that, medical research scientist Theobald Smith discovered what would be later known as Salmonella enterica (var. Choleraesuis). At the time, Smith was working as a research laboratory assistant in the Veterinary Division of the United States Department of Agriculture. The department was under the administration of Daniel Elmer Salmon, a veterinary pathologist.[10] Initially, Salmonella Choleraesuis was thought to be the causative agent of hog cholera, so Salmon and Smith named it "Hog-cholerabacillus". The name Salmonella was not used until 1900, when Joseph Leon Lignières proposed that the pathogen discovered by Daniel Salmon's group be called Salmonella in his honor.[11]:16

Detection, culture, and growth conditions

Most subspecies of Salmonella produce hydrogen sulfide,[12] which can readily be detected by growing them on media containing ferrous sulfate, such as is used in the triple sugar iron test. Most isolates exist in two phases: a motile phase I and a nonmotile phase II. Cultures that are nonmotile upon primary culture may be switched to the motile phase using a Craigie tube or ditch plate.[13]

Salmonella can also be detected and subtyped using multiplex[14] or real-time polymerase chain reactions (PCR)[15] from extracted Salmonella DNA.

Mathematical models of Salmonella growth kinetics have been developed for chicken, pork, tomatoes, and melons.[16][17][18][19][20] Salmonella reproduce asexually with a cell division interval of 40 minutes.[11]:16

Salmonella species lead predominantly host-associated lifestyles, but the bacteria were found to be able to persist in a bathroom setting for weeks following contamination, and are frequently isolated from water sources, which act as bacterial reservoirs and may help to facilitate transmission between hosts.[21]

The bacteria are not destroyed by freezing,[22][23] but UV light and heat accelerate their destruction—they perish after being heated to 55 °C (131 °F) for 90 min, or to 60 °C (140 °F) for 12 min.[24] To protect against Salmonella infection, heating food for at least 10 minutes to an internal temperature of 75 °C (167 °F) is recommended.[25][26]

Salmonella species can be found in the digestive tracts of humans and animals, especially reptiles. Salmonella on the skin of reptiles or amphibians can be passed to people who handle the animals.[27] Food and water can also be contaminated with the bacteria if they come in contact with the feces of infected people or animals.[28]

Nomenclature

Initially, each Salmonella "species" was named according to clinical considerations,[29] for example Salmonella typhi-murium (mouse typhoid fever), S. cholerae-suis. After it was recognized that host specificity did not exist for many species, new strains received species names according to the location at which the new strain was isolated. Later, molecular findings led to the hypothesis that Salmonella consisted of only one species,[30] S. enterica, and the serovars were classified into six groups,[31] two of which are medically relevant. As this now-formalized nomenclature[32][33] is not in harmony with the traditional usage familiar to specialists in microbiology and infectologists, the traditional nomenclature is still common. Currently, the two recognized species are S. enterica, and S. bongori. In 2005, a third species, Salmonella subterranean, was proposed, but according to the World Health Organization, the bacterium reported does not belong in the genus Salmonella.[34] The six main recognised subspecies are: enterica (serotype I), salamae (serotype II), arizonae (IIIa), diarizonae (IIIb), houtenae (IV), and indica (VI).[35] The former serotype (V) was bongori, which is now considered its own species.

The serovar, or serotype, is a classification of Salmonella into subspecies based on antigens that the organism presents. It is based on the Kauffman-White classification scheme that differentiates serological varieties from each other. Serotypes are usually put into subspecies groups after the genus and species, with the serovars/serotypes capitalized, but not italicized: An example is Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. More modern approaches for typing and subtyping Salmonella include DNA-based methods such as pulsed field gel electrophoresis, multiple-loci VNTR analysis, multilocus sequence typing, and multiplex-PCR-based methods.[36][37]

As pathogens

Salmonella species are facultative intracellular pathogens.[38] Many infections are due to ingestion of contaminated food. Salmonella serovars can be divided into two main groups—typhoidal and nontyphoidal Salmonella. Nontyphoidal serovars are more common, and usually cause self-limiting gastrointestinal disease. They can infect a range of animals, and are zoonotic, meaning they can be transferred between humans and other animals. Typhoidal serovars include Salmonella Typhi and Salmonella Paratyphi A, which are adapted to humans and do not occur in other animals.

Nontyphoidal Salmonella

Infection with nontyphoidal serovars of Salmonella generally results in food poisoning. Infection usually occurs when a person ingests foods that contain a high concentration of the bacteria. Infants and young children are much more susceptible to infection, easily achieved by ingesting a small number of bacteria. In infants, infection through inhalation of bacteria-laden dust is possible.

The organisms enter through the digestive tract and must be ingested in large numbers to cause disease in healthy adults. An infection can only begin after living salmonellae (not merely Salmonella-produced toxins) reach the gastrointestinal tract. Some of the microorganisms are killed in the stomach, while the surviving ones enter the small intestine and multiply in tissues. Gastric acidity is responsible for the destruction of the majority of ingested bacteria, but Salmonella has evolved a degree of tolerance to acidic environments that allows a subset of ingested bacteria to survive.[39] Bacterial colonies may also become trapped in mucus produced in the oesophagus. By the end of the incubation period, the nearby host cells are poisoned by endotoxins released from the dead salmonellae. The local response to the endotoxins is enteritis and gastrointestinal disorder.

About 2,000 serotypes of nontyphoidal Salmonella are known, which may be responsible for as many as 1.4 million illnesses in the United States each year. People who are at risk for severe illness include infants, elderly, organ-transplant recipients, and the immunocompromised.[28]

Invasive nontyphoidal salmonella disease

While in developed countries, nontyphoidal serovars present mostly as gastrointestinal disease; in sub-Saharan Africa, these serovars can create a major problem in bloodstream infections, and are the most commonly isolated bacteria from the blood of those presenting with fever. Bloodstream infections caused by nontyphoidal salmonellae in Africa were reported in 2012 to have a case fatality rate of 20–25%. Most cases of invasive nontyphoidal salmonella infection iNTS) are caused by S. typhimurium or S. enteritidis. A new form of Salmonella typhimurium (ST313) emerged in the southeast of the African continent 75 years ago, followed by a second wave which came out of central Africa 18 years later. This second wave of iNTS possibly originated in the Congo Basin, and early in the event picked up a gene that made it resistant to the antibiotic chloramphenicol. This created the need to use expensive antimicrobial drugs in areas of Africa that were very poor, making treatment difficult. The increased prevalence of iNTS in sub-Saharan Africa compared to other regions is thought to be due to the large proportion of the African population with some degree of immune suppression or impairment due to the burden of HIV, malaria, and malnutrition, especially in children. The genetic makeup of iNTS is evolving into a more typhoid-like bacterium, able to efficiently spread around the human body. Symptoms are reported to be diverse, including fever, hepatosplenomegaly, and respiratory symptoms, often with an absence of gastrointestinal symptoms.[40]

Typhoidal Salmonella

Typhoid fever is caused by Salmonella serotypes which are strictly adapted to humans or higher primates—these include Salmonella Typhi, Paratyphi A, Paratyphi B and Paratyphi C. In the systemic form of the disease, salmonellae pass through the lymphatic system of the intestine into the blood of the patients (typhoid form) and are carried to various organs (liver, spleen, kidneys) to form secondary foci (septic form). Endotoxins first act on the vascular and nervous apparatus, resulting in increased permeability and decreased tone of the vessels, upset of thermal regulation, and vomiting and diarrhoea. In severe forms of the disease, enough liquid and electrolytes are lost to upset the water-salt metabolism, decrease the circulating blood volume and arterial pressure, and cause hypovolemic shock. Septic shock may also develop. Shock of mixed character (with signs of both hypovolemic and septic shock) is more common in severe salmonellosis. Oliguria and azotemia may develop in severe cases as a result of renal involvement due to hypoxia and toxemia.

Global monitoring

In Germany, food poisoning infections must be reported.[41] Between 1990 and 2005, the number of officially recorded cases decreased from about 200,000 to about 50,000 cases. In the United States, about 50,000 cases of Salmonella infection are reported each year.[42] A World Health Organization study estimated that 21,650,974 cases of typhoid fever occurred in 2000, 216,510 of which resulted in death, along with 5,412,744 cases of paratyphoid fever.[43]

Molecular mechanisms of infection

Mechanisms of infection differ between typhoidal and nontyphoidal serovars, owing to their different targets in the body and the different symptoms that they cause. Both groups must enter by crossing the barrier created by the intestinal cell wall, but once they have passed this barrier, they use different strategies to cause infection.

Nontyphoidal serovars preferentially enter M cells on the intestinal wall by bacterial-mediated endocytosis, a process associated with intestinal inflammation and diarrhoea. They are also able to disrupt tight junctions between the cells of the intestinal wall, impairing the cells' ability to stop the flow of ions, water, and immune cells into and out of the intestine. The combination of the inflammation caused by bacterial-mediated endocytosis and the disruption of tight junctions is thought to contribute significantly to the induction of diarrhoea.[44]

Salmonellae are also able to breach the intestinal barrier via phagocytosis and trafficking by CD18-positive immune cells, which may be a mechanism key to typhoidal Salmonella infection. This is thought to be a more stealthy way of passing the intestinal barrier, and may, therefore, contribute to the fact that lower numbers of typhoidal Salmonella are required for infection than nontyphoidal Salmonella.[44] Salmonella cells are able to enter macrophages via macropinocytosis.[45] Typhoidal serovars can use this to achieve dissemination throughout the body via the mononuclear phagocyte system, a network of connective tissue that contains immune cells, and surrounds tissue associated with the immune system throughout the body.[44]

Much of the success of Salmonella in causing infection is attributed to two type III secretion systems which function at different times during infection. One is required for the invasion of nonphagocytic cells, colonization of the intestine, and induction of intestinal inflammatory responses and diarrhea. The other is important for survival in macrophages and establishment of systemic disease.[44] These systems contain many genes which must work co-operatively to achieve infection.

The AvrA toxin injected by the SPI1 type III secretion system of S. Typhimurium works to inhibit the innate immune system by virtue of its serine/threonine acetyltransferase activity, and requires binding to eukaryotic target cell phytic acid (IP6).[46] This leaves the host more susceptible to infection.

Salmonellosis is known to be able to cause back pain or spondylosis. It can manifest as five clinical patterns: gastrointestinal tract infection, enteric fever, bacteremia, local infection, and the chronic reservoir state. The initial symptoms are nonspecific fever, weakness, myalgia, etc. In the bacteremia state, it can spread to any parts of the body and this induces localized infection or it forms abscesses. The forms of localized Salmonella infections are arthritis, urinary tract infection, infection of the central nervous system, bone infection, soft tissue infection, etc.[47] Infection may remain as the latent form for a long time, and when the function of reticular endothelial cells is deteriorated, it may become activated and consequently, it may secondarily induce spreading infection in the bone several months or several years after acute salmonellosis.[47]

Resistance to oxidative burst

A hallmark of Salmonella pathogenesis is the ability of the bacterium to survive and proliferate within phagocytes. Phagocytes produce DNA damaging agents such as nitric oxide and oxygen radicals as a defense against pathogens. Thus, Salmonella must face attack by molecules that challenge genome integrity. Buchmeier et al.[48] showed that mutants of Salmonella enterica lacking RecA or RecBC protein function are highly sensitive to oxidative compounds synthesized by macrophages, and furthermore these findings indicate that successful systemic infection by S. enterica requires RecA and RecBC mediated recombinational repair of DNA damage.[48][49]

Host adaptation

Salmonella enterica, through some of its serovars such as Typhimurium and Enteriditis, shows signs of the ability to infect several different mammalian host species, while other serovars such as Typhi seem to be restricted to only a few hosts.[50] Some of the ways that Salmonella serovars have adapted to their hosts include loss of genetic material and mutation. In more complex mammalian species, immune systems, which include pathogen specific immune responses, target serovars of Salmonella through binding of antibodies to structures like flagella. Through the loss of the genetic material that codes for a flagellum to form, Salmonella can evade a host's immune system.[51] In the study by Kisela et al., more pathogenic serovars of S. enterica were found to have certain adhesins in common that have developed out of convergent evolution.[52] This means that, as these strains of Salmonella have been exposed to similar conditions such as immune systems, similar structures evolved separately to negate these similar, more advanced defenses in hosts. There are still many questions about the way that Salmonella has evolved into so many different types but it has been suggested that Salmonella evolved through several phases. As Baumler et al. have suggested, Salmonella most likely evolved through horizontal gene transfer, formation of new serovars due to additional pathogenicity islands and through an approximation of its ancestry.[53] So, Salmonella could have evolved into its many different serovars through gaining genetic information from different pathogenic bacteria. The presence of several pathogenicity islands in the genome of different serovars has lent credence to this theory.[53]

Genetics

In addition to its importance as a pathogen, Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium has been instrumental in the development of genetic tools that led to an understanding of fundamental bacterial physiology. These developments were enabled by the discovery of the first generalized transducing phage, P22,[54] in Typhimurium that allowed quick and easy genetic exchange that allowed fine structure genetic analysis. The large number of mutants led to a revision of genetic nomenclature for bacteria.[55] Many of the uses of transposons as genetic tools, including transposon delivery, mutagenesis, construction of chromosome rearrangements, were also developed in Typhimurium. These genetic tools also led to a simple test for carcinogens, the Ames Test.[56]

See also

- Host-pathogen interface

- 1984 Rajneeshee bioterror attack

- 2008 United States salmonellosis outbreak

- 2008–2009 peanut-borne salmonellosis

- Bismuth sulfite agar

- Food testing strips

- List of foodborne illness outbreaks

- Salmonellosis

- Wright County Egg

- Rappaport Vassiliadis soya peptone broth

- XLD agar

- American Public Health Association v. Butz

References

- ↑ Su, LH; Chiu, CH (2007). "Salmonella: clinical importance and evolution of nomenclature.". Chang Gung medical journal. 30 (3): 210–9. PMID 17760271.

- ↑ Tortora GA (2008). Microbiology: An Introduction] (9th ed.). Pearson. pp. 323–324. ISBN 8131722325.

- ↑ Ryan KJ, Ray CG (editors) (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. pp. 362–8. ISBN 0-8385-8529-9.

- 1 2 Fabrega, A.; Vila, J. (2013). "Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium Skills To Succeed in the Host: Virulence and Regulation". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 26 (2): 308–341. doi:10.1128/CMR.00066-12. ISSN 0893-8512.

- ↑ Brenner, FW; Villar, RG; Angulo, FJ; Tauxe, R; Swaminathan, B (July 2000). "Salmonella nomenclature.". Journal of clinical microbiology. 38 (7): 2465–7. PMID 10878026.

- ↑ editors; Gillespie, Stephen H.; Hawkey, Peter M. (2006). Principles and practice of clinical bacteriology (2nd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9780470017968.

- ↑ Okoro, Chinyere K; Kingsley, Robert A; Connor, Thomas R; Harris, Simon R; Parry, Christopher M; Al-Mashhadani, Manar N; Kariuki, Samuel; Msefula, Chisomo L; Gordon, Melita A; de Pinna, Elizabeth; Wain, John; Heyderman, Robert S; Obaro, Stephen; Alonso, Pedro L; Mandomando, Inacio; MacLennan, Calman A; Tapia, Milagritos D; Levine, Myron M; Tennant, Sharon M; Parkhill, Julian; Dougan, Gordon (30 September 2012). "Intracontinental spread of human invasive Salmonella Typhimurium pathovariants in sub-Saharan Africa". Nature Genetics. 44 (11): 1215–1221. doi:10.1038/ng.2423.

- ↑ Eberth, Prof C. J. (1880-07-01). "Die Organismen in den Organen bei Typhus abdominalis". Archiv für pathologische Anatomie und Physiologie und für klinische Medicin (in German). 81 (1): 58–74. doi:10.1007/BF01995472. ISSN 0720-8723.

- ↑ Hardy, A. (1999-08-01). "Food, hygiene, and the laboratory. A short history of food poisoning in Britain, circa 1850-1950". Social history of medicine: the journal of the Society for the Social History of Medicine / SSHM. 12 (2): 293–311. doi:10.1093/shm/12.2.293. ISSN 0951-631X. PMID 11623930.

- ↑ "FDA/CFSAN—Food Safety A to Z Reference Guide—Salmonella". FDA–Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition. 2008-07-03. Archived from the original on 2009-03-02. Retrieved 2009-02-14.

- 1 2 Heymann, Danielle A. Brands; Alcamo, I. Edward; Heymann, David L. (2006). Salmonella. Philadelphia: Chelsea House Publishers. ISBN 0-7910-8500-7. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ↑ Clark MA, Barret EL (June 1987). "The phs gene and hydrogen sulfide production by Salmonella typhimurium.Bacteriology". 169 (6): 2391–2397.

- ↑ "UK Standards for Microbiology Investigations: Changing the Phase of Salmonella" (PDF). UK Standards for Microbiology Investigations. Standards Unit, Public Health England: 8–10. 8 January 2015. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- ↑ Alvarez, Juan; Sota, Mertxe; Vivanco, Ana Belén; Perales, Ildefonso; Cisterna, Ramón; Rementeria, Aitor; Garaizar, Javier (2004-04-01). "Development of a Multiplex PCR Technique for Detection and Epidemiological Typing of Salmonella in Human Clinical Samples". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 42 (4): 1734–1738. doi:10.1128/JCM.42.4.1734-1738.2004. ISSN 0095-1137. PMC 387595

. PMID 15071035.

. PMID 15071035. - ↑ Hoorfar, J.; Ahrens, P. (September 2000). "Automated 5′ Nuclease PCR Assay for Identification of Salmonella enterica". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. American Society for Microbiology. 38 (9): 3429–3435. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- ↑ Dominguez, Silvia A. "Modelling the Growth of Salmonella in Raw Poultry Stored under Aerobic Conditions".

- ↑ Carmen Pin. "Modelling Salmonella concentration throughout the pork supply chain by considering growth and survival in fluctuating conditions of temperature, pH and a". International Journal of Food Microbiology. 145: S96–S102. doi:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2010.09.025.

- ↑ Pan, Wenjing. "Modelling the Growth of Salmonella in Cut Red Round Tomatoes as a Function of Temperature".

- ↑ Li, Di. "Development and Validation of a_w Mathematical Model for Growth of Pathogens in Cut Melons". Journal of Food Protection. 76: 953–958. doi:10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-12-398.

- ↑ Li, Di. "Development and validation of a mathematical model for growth of salmonella in cantaloupe".

- ↑ Winfield, Mollie; Eduardo Groisman (2003). "Role of Nonhost Environments in the Lifestyles of Salmonella and Escerichia coli". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 69 (7): 3687–3694. doi:10.1128/aem.69.7.3687-3694.2003.

- ↑ Sorrells, K.M.; M. L. Speck; J. A. Warren (January 1970). "Pathogenicity of Salmonella gallinarum After Metabolic Injury by Freezing". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 19 (1): 39–43. PMC 376605

. PMID 5461164. Retrieved 2010-08-19.

. PMID 5461164. Retrieved 2010-08-19. Mortality differences between wholly uninjured and predominantly injured populations were small and consistent (5% level) with a hypothesis of no difference.

- ↑ Beuchat, L. R.; E. K. Heaton (June 1975). "Salmonella Survival on Pecans as Influenced by Processing and Storage Conditions". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 29 (6): 795–801. PMC 187082

. PMID 1098573. Retrieved 2010-08-19.

. PMID 1098573. Retrieved 2010-08-19. Little decrease in viable population of the three species was noted on inoculated pecan halves stored at -18, -7, and 5°C for 32 weeks.

- ↑ Goodfellow, S.J.; W.L. Brown (August 1978). "Fate of Salmonella Inoculated into Beef for Cooking". Journal of Food Protection Vol. 41 No.8. 41 (8): 598–605.

- ↑ Partnership for Food Safety Education (PFSE) Fight BAC! Basic Brochure.

- ↑ USDA Internal Cooking Temperatures Chart. The USDA has other resources available at their Safe Food Handling fact-sheet page. See also the National Center for Home Food Preservation.

- ↑ "Reptiles, Amphibians, and Salmonella". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. 25 November 2013. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

- 1 2 Goldrick, Barbara (2003). "Foodborne Diseases: More efforts needed to meet the Healthy People 2010 objectives". The American Journal of Nursing. 103 (3): 105–106. doi:10.1097/00000446-200303000-00043. Retrieved 6 December 2014.

- ↑ F. Kauffmann: Die Bakteriologie der Salmonella-Gruppe. Munksgaard, Kopenhagen, 1941

- ↑ Minor L. Le; Popoff M. Y. (1987). "Request for an Opinion. Designation of Salmonella enterica. sp. nov., nom. rev., as the type and only species of the genus Salmonella". Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 37: 465–468.

- ↑ Reeves MW, Evins GM, Heiba AA, Plikaytis BD, Farmer JJ (February 1989). "Clonal nature of Salmonella typhi and its genetic relatedness to other salmonellae as shown by multilocus enzyme electrophoresis, and proposal of Salmonella bongori comb. nov". J. Clin. Microbiol. 27 (2): 313–20. PMC 267299

. PMID 2915026.

. PMID 2915026. - ↑ "The type species of the genus Salmonella Lignieres 1900 is Salmonella enterica (ex Kauffmann and Edwards 1952) Le Minor and Popoff 1987, with the type strain LT2T, and conservation of the epithet enterica in Salmonella enterica over all earlier epithets that may be applied to this species. Opinion 80". Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 55 (Pt 1): 519–20. January 2005. doi:10.1099/ijs.0.63579-0. PMID 15653929.

- ↑ Tindall BJ, Grimont PA, Garrity GM, Euzéby JP (January 2005). "Nomenclature and taxonomy of the genus Salmonella". Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 55 (Pt 1): 521–4. doi:10.1099/ijs.0.63580-0. PMID 15653930.

- ↑ Grimont, Patrick A.D.; Xavier Weill, François (2007). Antigenic Formulae of the Salmonella Serovars (PDF) (9th ed.). Institut Pasteur, Paris, France: WHO Collaborating Centre for Reference and Research on Salmonella. p. 7. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ↑ Janda JM, Abbott SL (2006). "The Enterobacteria", ASM Press.

- ↑ Porwollik, S (editor) (2011). Salmonella: From Genome to Function. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-73-8.

- ↑ Achtman, M.; Wain, J.; Weill, F. O. X.; Nair, S.; Zhou, Z.; Sangal, V.; Krauland, M. G.; Hale, J. L.; Harbottle, H.; Uesbeck, A.; Dougan, G.; Harrison, L. H.; Brisse, S.; S. Enterica MLST Study Group (2012). Bessen, Debra E, ed. "Multilocus Sequence Typing as a Replacement for Serotyping in Salmonella enterica". PLOS Pathogens. 8 (6): e1002776. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002776. PMC 3380943

. PMID 22737074.

. PMID 22737074.

- ↑ Jantsch, J.; Chikkaballi, D.; Hensel, M. (2011). "Cellular aspects of immunity to intracellular Salmonella enterica". Immunological Reviews. 240 (1): 185–195. doi:10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00981.x. PMID 21349094.

- ↑ Garcia-del Portillo, Francisco; John W. Foster; Brett Finlay (1993). "Role of Acid Tolerance Response Genes in Salmonella tymphimurium Virulence". Infection and Immunity. 61 (10): 4489–4492.

- ↑ Feasey, Nicholas A.; Gordon Dougan; Robert A. Kingsley; Robert S. Heyderman; Melita A. Gordon (2012). "Invasive non-typhoidal salmonella disease: an emerging and neglected tropical disease in Africa". The Lancet. 379: 2489–2499. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61752-2.

- ↑ § 6 and § 7 of the German law on infectious disease prevention, Infektionsschutzgesetz

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- ↑ Crump, John A.; Luby, Stephen P.; Mintz, Eric D. (May 2004). "The global burden of typhoid fever.". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 82 (5): 346–353. PMC 2622843

. PMID 15298225.

. PMID 15298225. - 1 2 3 4 Haraga, Andrea; Maikke B. Ohlson; Samuel I. Miller (2008). "Salmonellae interplay with host cells". Nature Reviews Microbiology. 6: 53–66. doi:10.1038/nrmicro1788.

- ↑ Kerr, M. C.; Wang, J. T. H.; Castro, N. A.; Hamilton, N. A.; Town, L.; Brown, D. L.; Meunier, F. A.; Brown, N. F.; Stow, J. L.; Teasdale, R. D. (2010). "Inhibition of the PtdIns(5) kinase PIKfyve disrupts intracellular replication of Salmonella". The EMBO Journal. 29 (8): 1331–1347. doi:10.1038/emboj.2010.28. PMC 2868569

. PMID 20300065.

. PMID 20300065. - ↑ Mittal R, Peak-Chew SY, Sade RS, Vallis Y, McMahon HT (2010). "The Acetyltransferase Activity of the Bacterial Toxin YopJ of Yersinia Is Activated by Eukaryotic Host Cell Inositol Hexakisphosphate". J Biol Chem. 285 (26): 19927–34. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.126581. PMC 2888404

. PMID 20430892.

. PMID 20430892. - 1 2 Choi YS, Cho WJ, Yun SH, Lee SY, Park SH, Park JC, Jang EH, Shin HY (2010). "A case of back pain caused by Salmonella spondylitis -A case report-". Korean J Anesthesiol. 59 Suppl: S233–7. doi:10.4097/kjae.2010.59.S.S233. PMC 3030045

. PMID 21286449.

. PMID 21286449. - 1 2 Buchmeier NA, Lipps CJ, So MY, Heffron F (1993). "Recombination-deficient mutants of Salmonella typhimurium are avirulent and sensitive to the oxidative burst of macrophages". Mol. Microbiol. 7 (6): 933–6. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01184.x. PMID 8387147.

- ↑ Cano DA, Pucciarelli MG, García-del Portillo F, Casadesús J (2002). "Role of the RecBCD recombination pathway in Salmonella virulence". J. Bacteriol. 184 (2): 592–5. doi:10.1128/jb.184.2.592-595.2002. PMC 139588

. PMID 11751841.

. PMID 11751841. - ↑ Thomson, Nicholas R.; Clayton, Debra J.; Windhorst, Daniel; et al. (2008). "Comparative genome analysis of Salmonella Enteritidis PT4 and Salmonella Gallinarum 287/91 provides insights into evolutionary and host adaptation pathways". Genome Res. 18: 1624–1637. doi:10.1101/gr.077404.108.

- ↑ Pang, Stanley. Octavia, Sophie. Feng, Lu. Liu, Bin. Reeves, Peter R. Lan, Ruiting. Wang, Lei (2011). "Genomic diversity and adaptation of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium from analysis of six genomes of different phage types". BMC Genomics. 12: 425. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-12-425.

- ↑ Kisiela, D. I.; Chattopadhyay, S.; Libby, S. J.; Karlinsey, J. E.; Fang, F. C.; et al. (2012). "Evolution of Salmonella enterica Virulence via Point Mutations in the Fimbrial Adhesin". PLoS Pathog. 8 (6): e1002733. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002733.

- 1 2 Bäumler, Andreas J.; Tsolis, Renée M.; Ficht, Thomas A.; Adams, L. Garry (1998). "Evolution of Host Adaptation in Salmonella enterica". Infect. Immun. 66 (10): 4579–4587. PMC 108564

. PMID 9746553.

. PMID 9746553. - ↑ Zinder N, Lederberg J (1952). "Genetic exchange in Salmonella" (PDF). J. Bacteriol. 64 (5): 679–699. PMC 169409

. PMID 12999698.

. PMID 12999698. - ↑ Demerec, M.; A. Adelberg; A. J. Clark; P. Hartman (1966). "A proposal for a uniform nomenclature in bacterial genetics" (PDF). Genetics. 54 (1): 61–76. PMC 1211113

. PMID 5961488.

. PMID 5961488. - ↑ Ames, B.; J. McCann; E. Yamasaki (1975). "Methods for detecting carcinogens and mutagens with the Salmonella/mammalian-microsome mutagenicity test". Mutat Res. 31 (6): 347–364. doi:10.1016/0165-1161(75)90046-1. PMID 768755.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Salmonella. |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Salmonella |

- Background on Salmonella from the Food Safety and Inspection Service of the United States Department of Agriculture

- Salmonella genomes and related information at PATRIC, a Bioinformatics Resource Center funded by NIAID

- Questions and Answers about commercial and institutional sanitizing methods

- Symptoms of Salmonella Poisoning

- Salmonella as an emerging pathogen from IFAS

- Notes on Salmonella nomenclature

- Salmonella motility video

- Avian Salmonella

- Overview of Salmonellosis — The Merck Veterinary Manual