Russian Liberation Army

| Russian Liberation Army (Russian: Русская освободительная армия), (German: Russische Befreiungsarmee) | |

|---|---|

|

General Vlasov and soldiers of the ROA | |

| Active | 1944 (officially) – 1945 |

| Allegiance |

|

| Type |

Infantry Air force |

| Size | Corps, 120,000 – 130,000 (April 1945) |

| Nickname(s) | Vlasovtsy (Власовцы) |

| March | We Go on the Wide Fields (Мы идём широкими полями) |

| Engagements |

|

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders |

Andrey Vlasov Sergei Bunyachenko Mikhail Meandrov Viktor Maltsev |

| Insignia | |

| Badge |

|

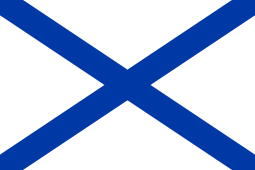

| Flag of the KONR |

|

The Russian Liberation Army (Russian: Русская освободительная армия, Russkaya osvoboditel'naya armiya, abbreviated in Cyrillic as РОА, in Latin as ROA, also known as the Vlasov army) was a group of predominantly Russian forces that fought under German command during World War II. The army was led by Andrey Vlasov, a defected Red Army general, and members of the army are often referred to as Vlasovtsy (Власовцы). In 1944, it became known as the Armed Forces of the Committee for the Liberation of the Peoples of Russia (Вооружённые силы Комитета освобождения народов России, ВС КОНР, VS-KONR in Latin).

The ROA was organized by former Red Army general Andrey Vlasov, who tried to unite Russians opposed to communism and to the Soviet leader Joseph Stalin with the goal of fighting with Germany to liberate Russia. The volunteers were mostly Soviet prisoners of war but also included White Russian émigrés (some of whom were veterans of the anti-communist White Army from the Russian Civil War). On 14 November 1944 it was officially renamed the Armed Forces of the Committee for the Liberation of the Peoples of Russia, with the KONR being formed as political body for the army to be loyal to. On 28 January 1945, it was officially declared that the Russian divisions no longer formed part of the German Army, but would directly be under the command of KONR.

Origins

Russian volunteers who enlisted into the German Army (Wehrmacht Heer) wore the patch of the Russian Liberation Army, an army which did not yet exist but was presented as a reality by Nazi propaganda. These volunteers (called Hiwi, an acronym for Hilfswilliger, roughly meaning "volunteers") were not under any Russian command or control; they were exclusively under German command carrying out various noncombat duties. A number of them were employed at the Battle of Stalingrad, where it was estimated that as much as one quarter of the 6th Army's strength were Soviet citizens. Soon, several German commanders began forming small armed units out of them for various tasks, including combat against Soviet partisans, driving vehicles, carrying wounded, and delivering supplies.[2]

Adolf Hitler allowed the idea of the Russian Liberation Army to circulate in propaganda literature so long as no real formations of the sort were permitted. As a result, some Red Army soldiers surrendered or defected in hopes of joining an army that did not yet exist. Many Soviet prisoners of war volunteered to serve under the German command just in order to get out from Nazi POW camps which were notorious for starving Soviet prisoners to death.

Meanwhile, the newly captured Soviet general Andrei Andreevich Vlasov, along with his German and Russian allies, was desperately lobbying the German high command, hoping that a green light would be given for the formation of a real armed force that would be exclusively under Russian control. They were able to somewhat win over Alfred Rosenberg.[3]

Hitler's staff repeatedly rejected these appeals with hostility, refusing to even consider them. Still, Vlasov and his allies reasoned that Hitler would eventually come to realize the futility of a war against the USSR with the hostility of the Russian people and respond to Vlasov's demands.

Irrespective of the political wrangling over Vlasov and the status of the ROA, the reality by mid-1943 was several hundred thousand ex-Soviet volunteers were serving in the German forces, either as Hiwis or in Eastern volunteer units (referred to as Osteinheiten or landeseigene Verbände). These latter were generally deployed in a security role in the rear areas of the armies and army groups in the East, where they constituted a major part of the German capacity to counter the activity of Soviet partisan forces, dating as far back as early 1942. The Germans were, however, always concerned about their reliability, and with the German setbacks in the summer of 1943 this situation took a turn for the worse. On 12 September for example, 2nd Army had to withdraw Sturm-Btl. AOK 2 in order to deal with what is described as “several mutinies and desertions of Eastern units". A 14 September communication from the army states that in the recent period, Hiwi absenteeism had risen strongly.[4] Following a series of mutinies attempted or successful and a surge in desertions,[5] they decided in September 1942 that the reliability of these units had fallen to levels where they were more a liability than an asset. In an October 1943 report, 8th Army concluded grimly: "All local volunteers are unreliable during enemy contact. Principal reason of unreliability is the employment of these volunteers in the East."[6] Two days previously, army had recorded in the KTB stern measures to be taken in the event of further cases of rebellion or unreliability, investing in regimental commanders far-reaching powers to perform summary courts and execute the verdicts.

Since it was considered that it would improve their reliability if they were removed from contact with the local population, it was decided to send them to the West,[7] which the majority of them were in late 1943 and early 1944.[8]

A large number of these battalions were hence integrated into the Divisions in the West. A number of such soldiers were on guard in Normandy on D-Day, and without the equipment or the motivation to fight the Allies, most promptly surrendered. There were instances of bitter fighting to the very end, triggered by mishandled propaganda from the Allies that accurately told of the quick repatriation of soldiers back to the Soviet Union after they gave up.

A total of 71 "Eastern" battalions served on the Eastern Front, while 42 battalions served in Belgium, Finland, France, and Italy.

An aerial component from Russian volunteers was formed as Ostfliegerstaffel (russische) in December 1943, only to be disbanded before seeing combat in July 1944. The Russian airmen were regrouped into the Night Harassment Squadron 8, whose first and only mission took place on 13 April 1945, when they attacked a Soviet bridgehead at Erlenhof, on the Oder River.

Formation of ROA and the fight against Red Army

The ROA did not officially exist until autumn of 1944, after Heinrich Himmler persuaded a very reluctant Hitler to permit the formation of 10 Russian Liberation Army divisions.

On 14 November in Prague, Vlasov read aloud the Prague Manifesto before the newly created Committee for the Liberation of the Peoples of Russia. This document stated the purposes of the battle against Stalin, and spelled out 14 democratic points which the army was fighting for. German insistence that the document carry anti-Semitic rhetoric was successfully parried by Vlasov's committee; however, they were obliged to include a statement criticising the Western Allies, labelling them "plutocracies" that were "allies of Stalin in his conquest of Europe".

By February 1945, only one division, the 1st Infantry (600th Infantry) was fully formed, under the command of General Sergei Bunyachenko. Formed at Münsingen, it fought briefly on the Oder Front before switching sides and helping the Czechs liberate Prague.

A second division, the 2nd Infantry (650th Infantry), was incomplete when it left Lager Heuberg but was put into action under the command of General Mikhail Meandrov. This division was joined in large numbers by eastern workers which caused it to nearly double in size as it headed on its march south. A third, the 3rd Infantry (700th German Infantry), only began formation.

Several other Russian units, such as the Russian Corps, XVth SS Cossack Cavalry Corps of General Helmuth von Pannwitz, the Cossack Camp of Ataman Domanov, and other primarily White émigré formations had agreed to become a part of Vlasov's army. However, their membership remained de jure as the turn of events did not permit Vlasov to use these men in any operation (even reliable communications were often impossible).

A small group of ROA volunteers fought against the Red Army on 9 February 1945. Their fighting vigor gained them the praise of Heinrich Himmler.[9] The only active combat the Russian Liberation Army undertook against the Red Army was by the Oder on 11 April 1945, done largely at the insistence of Himmler as a test of the army's reliability. After three days, the outnumbered 1st Division had to retreat.

On 28 January 1945, it was officially declared that the Russian divisions no longer formed part of the German Army, but would directly be under the command of KONR.[1]

Vlasov then ordered the first division to march south to concentrate all Russian anticommunist forces loyal to him. As the army, he reasoned, they could all surrender to the Allies on "favorable" (no repatriation) terms. Vlasov sent several secret delegations to begin negotiating a surrender to the Allies, hoping they would sympathise with the goals of ROA and potentially use it in an inevitable future war with the USSR.

Fight against the Germans and capture by the Soviets

During the march south, the first division of the ROA came to the help of the Czech insurgents to support the Prague uprising which started on May 5, 1945, against the German occupation. Vlasov was initially reluctant, but ultimately did not resist General Bunyachenko's decision to fight against the Germans.[10]

The first division engaged in battle with Waffen-SS units that had been sent to level the city. The ROA units armed with heavy weaponry fended off the relentless SS assault, and together with the Czech insurgents succeeded in preserving most of Prague from destruction. Due to the predominance of communists in the new Czech Rada ("council"), the first division had to leave the city the very next day and tried to surrender to US Third Army of General Patton. The Allies, however, had little interest in aiding or sheltering the ROA, fearing such aid would severely harm relations with the USSR. Soon after the failed attempt to surrender to the Americans, Vlasov and many of his men were caught by the Soviets.[10]

More than a thousand soldiers were initially taken into allied custody by the 44th Division and other U.S. troops. They were then forcefully extradited to the Soviets by the Allies, due to a previous agreement between Churchill and Stalin that all ROA soldiers be returned to the USSR. Vlasov was in this group, but the Soviets claimed his capture. The Allied command kept this secret for many years. However, some allied officers who were sympathetic to the ROA soldiers permitted them to escape in small groups into the American controlled zones.[11]

The Soviet government labelled all ROA soldiers (vlasovtsy) as traitors. The ROA soldiers who were repatriated were tried and sentenced to detention in prison camps. Vlasov and several other leaders of the ROA were tried and hanged in Moscow on August 1, 1946.

Order of battle

The composition of the VS-KONR was as follows:[1][9]

| Division | Commander | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 600th (Russian) Infantry Division 1st Division of the KONR | Major General Sergei Bunyachenko | Included members of the disbanded Kaminsky Brigade. Had a total of around 20,000 men. |

| 650th (Russian) Infantry Division 2nd Division of the KONR | Major General Grigory Zverev | Not fully armed or prepared, had 11,856 men. |

| 700th (Russian) Infantry Division 3rd Division of the KONR | Major General Mikhail Shapalov | Did not finish forming, had about 10,000 unarmed men. |

Air elements

- I. Ostfliegerstaffel (russische) (1st Eastern Squadron-Russian) (1943-1944)

- II. Störkampfstaffel (Night Harassment Squadron) 8 (1945)

- KONR Air Force

Two former Soviet Air Force ace pilots, Semyon Trofimovich Bychkov and Bronislav Romanovich Antilevsky, defected and became part of the ROA air forces. The air force was later disbanded in July 1944.[10] The air force was commanded by Major General Viktor Maltsev.[10]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Russian Liberation Army. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Ukrainian Liberation Army

- Ukrainian National Army

- Ostlegionen (mainly units of peoples from the Caucasus)

- Russian Liberation Movement

- Kaminski Brigade

- Lokot Republic

- Operation Keelhaul

- Russian Corps

- Russian All National Popular State Movement

- Collaboration during World War II

- Russian Monument (Liechtenstein)

- Victims of Yalta, a 1977 book by Nikolai Tolstoy detailing the forced repatriation of Soviet people after World War II

- Repatriation of Cossacks after World War II

- Wehrmacht foreign volunteers and conscripts

References

- 1 2 3 Jurado, Carlos (1983). Foreign Volunteers of the Wehrmacht 1941-45. Osprey Publishing. p. 28. ISBN 0-85045-524-3.

- ↑ Ellis, Frank. The Stalingrad Cauldron: Inside the Encirclement and Destruction of 6th Army. N.p.: U of Kansas, 2013. Print.

- ↑ Russian Volunteers in the Wehrmacht

- ↑ Bundesarchiv-Militärarchiv (BA-MA) RH20-2/558 ”Entweichen von HiWi”, AOK 2 Ia 3385/43, 14.9.43

- ↑ There are many reports of such incidents in the reporting of the army commands in the East. See f.e. BA-MA RH20-2/636. AOK 2 Ia 2749/43, 9.8.43, RH20-2/558 (concern over the night mutinies)(”Bericht über die Meutereien in der Nacht vom 12. zum 13.9.43“, 16.9.43, RH20-2/558 ”Bericht über die geplante Meuterei in der Nacht vom 19. zum 20.9.1943“, 23.9.43, RH20-2/558 Komm.d.rückw. Armee-gebiet 580 3666/43, 30.9.43, RH20-2/558 „Zuverlässigkeit der Ostverbänden“, “ Komm. Der Osttruppen z.b.v. 720 beim Aok 2 1042/43, 7.10.43

- ↑ RH20-8/979 >„Zuverlässigkeit landeseigener Verbände“, AOK 8 Ia 4844/3, 1.10.43 "“Alle landeseigenen Verbände sind bei Feindberührung unzuverlässig. Hauptgrunde der Unzuverlässigkeit sind der Einsatz der Verbände im Osten“.

- ↑ Recorded for instance in RH20-2/558 ”Verlegung von Landeseigenen Verbänden“ AOK 2 Ia 989/43, 30.9.43

- ↑ A 4 November 2nd Army report names just 9 units (it had more than 60 in September) who were to remain with the Army, the rest having been or being in the process of transfer West, or disbandment. (See RH20-2/558 ”Auskämmaktion unzuverlässiger Ostverbände” AOK 2 Ia 4454/43, 4.11.43). An Army Group Center report ( RH20-2/558 ”Zusammenstellung über Osttruppen”, HG Mitte Ia 12303/43, 25.10.43) identifies 16 battalions and several companies who had already departed for the West by late October, with an additional 20 (again, plus several companies) designated for transfer and a further 12 being prepared.

- 1 2 Müller, Rolf-Dieter. The Unknown Eastern Front: The Wehrmacht and Hitler's Foreign Soldiers. London: I.B. Tauris, 2012. Print.

- 1 2 3 4 Vlasov and the Russian Liberation Army. A Journey Through Russian Culture. Published 22 June 2010. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- ↑ Based on the unpublished account of the 44th Division intelligence officer who met with Vlasov and negotiated his surrender in Austria. The surrender involved assurances from SHEAF headquarters in Paris that the ROA who surrendered to the Americans would not be sent back to the Soviets. His account remained unpublished because at the time of his death it was still considered highly secret.

Sources

- The Gulag Archipelago: 1918-1956 by Aleksandr I. Solzhenitsyn

- Army of the Damned: on Twentieth Century - CBS Documentary Documentary Series - December 1962

External links

- Articles

- It's Too Early To Forgive Vlasov, The St. Petersburg Times, November 6, 2001

- Other

- Russian Liberation Army information page by veteran Alexander Dubov

- Russian Volunteers in the German Wehrmacht in World War II by Lt. Gen Wladyslaw Anders and Antonio Munoz

- Russian Liberation Army, rare footage (video)