Rupert D'Oyly Carte

Rupert D'Oyly Carte (3 November 1876 – 12 September 1948) was an English hotelier, theatre owner and impresario, best known as proprietor of the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company and Savoy Hotel from 1913 to 1948.

Son of the impresario and hotelier Richard D'Oyly Carte, Rupert inherited the family businesses from his stepmother Helen. After serving in World War I, he took steps to revitalise the opera company, which had not appeared in Central London since 1909, hiring new designers and conductors to present fresh productions of the Gilbert and Sullivan operas in seasons in the West End. The new productions generally retained the original text and music of the operas. Carte launched international and provincial tours, as well as the London seasons, and he released the first complete recordings of the operas. He also rebuilt the half-century-old Savoy Theatre in 1929, opening the house with a season of Gilbert and Sullivan.

As an hotelier, Carte built on his father's legacy, expanding the Savoy Hotel, refreshing the other hotels and restaurants in the Savoy group, including Claridge's and the Berkeley Hotel, and introducing cabaret and dance bands that became internationally famous. He also increased marketing activities, including foreign marketing, of the hotels.

P. G. Wodehouse based a character in his novels, Psmith, on a Wykehamist schoolboy whom he identified as Rupert D'Oyly Carte. At his death, Carte passed the opera company and hotels to his only surviving child, Bridget D'Oyly Carte. The Gilbert and Sullivan operas, nurtured by Carte and his family for over a century, continue to be produced frequently today throughout the English-speaking world and beyond.

Life and career

Early life

Rupert D'Oyly Carte was born in Hampstead, London, the younger son of the impresario Richard D'Oyly Carte and his first wife Blanche (née Prowse), who died in 1885. Like his brother, Lucas (1872–1907), he was given his father's middle name. He was educated at Winchester College, noted as among the most intellectually rigorous of English public schools.[1] He then worked for a firm of accountants before joining his father as an assistant in 1894.[2]

In a newspaper interview given in the year of his death, Rupert recalled that as a young man he was entrusted, during his father's illness, with helping W. S. Gilbert with the first revival of The Yeomen of the Guard at the Savoy Theatre.[3] He was elected a director of the Savoy Hotel Limited in 1898, joining his father and Sir Arthur Sullivan, who had served on the board since the Savoy Hotel was built.[4] By 1899 he was assistant managing director.[5] Richard D'Oyly Carte died in 1901, and Rupert's stepmother, the former Helen Lenoir, who had married Richard in 1888, assumed full control of most of the family businesses, which she had increasingly controlled during her husband's decline. Rupert's elder brother, Lucas, a barrister, was not involved in the family businesses and died of tuberculosis, aged 34.[6]

Taking over the family businesses

In 1903, at the age of 27, Rupert took over his late father's role as chairman of the Savoy group, which included the Savoy Hotel, Claridge's, The Berkeley Hotel, Simpson's-in-the-Strand and the Grand Hotel in Rome. At this time, the whole group was officially valued at £2,221,708.[7] He immediately issued £300,000 of debentures to raise capital for a large extension to the Savoy (the "East Block").[7] Like his father, Carte was willing to go to great lengths to secure the best employees for his hotels. When Claridge's needed a new chef in 1904, he secured the services of François Bonnaure, formerly chef at the Élysée Palace in Paris. The press speculated on how much Carte must have paid to persuade Bonnaure to join him, and compared the younger Carte's audacity with his father's coup in securing Paris's most famous maître d'hôtel, M. Joseph, a few years earlier.[8]

Between 1906 and 1909, Helen Carte,[9] Rupert's stepmother, staged two repertory seasons at the Savoy Theatre. Directed by Gilbert and received with much success, they revitalised the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company, which had been in decline after Richard D'Oyly Carte's death.[10] In 1912, when theatre censorship was under discussion in Britain, Carte was strongly in favour of retaining censorship, because it gave managements complete certainty about what they could or could not stage without fear of interference by the police or others. He joined with other London theatre managers, including Herbert Beerbohm Tree, George Edwardes and Arthur Bourchier in signing a petition for the retention of censorship.[11] In the same year, together with Herbert Sullivan and theatre managers including Beerbohm Tree and Squire Bancroft, Carte was an instigator of a memorial to W. S. Gilbert at Charing Cross.[12] In 1913, Rupert's stepmother Helen Carte died. She left all her holdings in the Savoy Hotel group, the Savoy Theatre and the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company to her stepson.[13]

Revitalising the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company

After London seasons in 1906–07 and 1908–09, the opera company did not perform in the West End again until 1919, although it continued to tour in Great Britain.[14] According to the theatre writer H. M. Walbrook, "Through the years of the Great War they continued to be on tour through the country, drawing large and grateful audiences everywhere. They helped to sustain the spirits of the people during that stern period, and by so doing they helped to win the victory."[15] Nevertheless, Carte later recalled, "I went and watched the Company playing at a rather dreary theatre down in the suburbs of London. I thought the dresses looked dowdy.... I formed the view that new productions should be prepared, with scenery and dresses to the design of first class artists who understood the operas but who would produce a décor attractive to the new generation."[16] In a 1922 memoir, Henry Lytton, having admired Richard D'Oyly Carte's keen eye for stagecraft, added, "That 'eye' for stagecraft ... has been inherited in a quite remarkable degree by his son, Mr. Rupert D'Oyly Carte. He, too, has the gift of taking in the details of a scene at a glance, and knowing instinctively just what must be corrected".[17] In 1911, the company hired J. M. Gordon as stage manager, and Carte later promoted him to director. Gordon, under Carte's supervision, preserved the company's traditions in exacting detail for 28 years.[18]

During World War I Carte served in the Royal Navy,[19] and no renovation work could be undertaken.[20] On his return, he put his aims into effect. In an interview in The Observer in August 1919 he set out his policy for staging the operas: "They will be played precisely in their original form, without any alteration to the words, or any attempt to bring them up to date."[21] This uncompromising declaration was modified in a later interview in which he said, "the plays are all being restaged ... Gilbert's words will be unaltered, though there will be some freshness in the method of rendering them. Artists must have scope for their individuality, and new singers cannot be tied down to imitate slavishly those who made successes in the old days."[19]

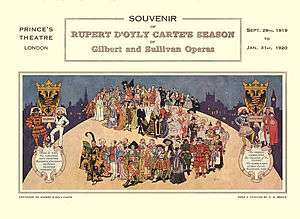

Carte's first London season, at the Prince's Theatre, 1919–20, featured ten of the thirteen extant Gilbert and Sullivan operas.[22] These included Princess Ida, which had its first London performances since the original production.[23] The new productions retained the text and music of the original 1870s and 1880s productions, and director J. M. Gordon preserved much of Gilbert's original direction. As his parents had done, Carte licensed the operas to the J. C. Williamson company and to amateur companies, but he required all licensees to present them in approved productions that closely followed the libretto, score and D'Oyly Carte production stagings.[24] In an interview with The Times in 1922, Carte said that the Savoy "tradition" was an expression that was frequently misunderstood: "It did not by any means imply any hidebound stage 'business' or an attempt to standardize the performances of artists so as to check their individual method of expression. All that it implied, in his view, was the highest possible standard of production – with especial attention to clear enunciation.... Many people seemed to think that Gilbert believed in absolutely set methods but this was not by any means the case. He did not hesitate to alter productions when they were revived."[25]

Although he had told the press that the original words and music would not be altered, Carte was willing to make changes in certain cases. In 1919–20, he authorised significant cuts and alterations in both Princess Ida and Ruddigore. In 1921 Cox and Box was produced in a drastically cut-down version, to allow it to be played as a companion piece with the shorter Savoy operas. He also authorised changes to Gilbert's text: he wrote to The Times in 1948, "We found recently in America that much objection was taken by coloured persons to a word used twice in The Mikado." The word in question was Gilbert's reference to "nigger" (blackface) minstrels, and Carte asked A. P. Herbert to suggest an acceptable revision. "He made several alternative suggestions, one of which we adopted in America, and it seems well to go on doing so in the British Empire."[26]

Carte commissioned new costumes and scenery throughout his tenure with the company. For his restagings, Carte hired Charles Ricketts to redesign The Gondoliers and The Mikado, the costumes for the latter, created in 1926, being retained by all the company's subsequent designers. Other redesigns were by Percy Anderson, George Sheringham, Hugo Rumbold and Peter Goffin, a protégé of Carte's daughter, Bridget D'Oyly Carte.

For London seasons, Carte often engaged guest conductors, first Geoffrey Toye, then Malcolm Sargent, who examined Sullivan's manuscript scores and purged the orchestral parts of accretions. So striking was the orchestral sound produced by Sargent that the press thought he had retouched the scores, and Carte had the pleasant duty of correcting their error. In a letter to The Times, he noted that "the details of the orchestration sounded so fresh that some of the critics thought them actually new ... the opera was played last night exactly as written by Sullivan."[27] Carte also hired Harry Norris, who started with the touring company, then was Toye's assistant before becoming musical director. Isidore Godfrey joined the company as assistant musical director in 1925 and became musical director in 1929, remaining in that post until 1968.

|

Major-General's Song

George Baker singing the Major-General's Song from the company's 1929 recording of Pirates, conducted by Malcolm Sargent |

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

The possibilities of the gramophone appealed to Carte. After World War I, he supervised a series of complete recordings of the scores of the operas on the HMV label, beginning with The Mikado in 1918.[28] The first nine sets, made between 1918 and 1925, were recorded by the early acoustic process. At first, guest singers were chosen who were known for their ability to record well on this technology. Later in this series, more of the regular members of the company were featured.[29] With the introduction of electrical recording and its greatly improved recording process and sound, a new round of recordings began in 1927.[30] For the electrical series, Carte's own singers were mostly used.[31] Carte also recognised the potential of radio and worked with the BBC to relay live broadcasts of D'Oyly Carte productions. A 1926 relay of part of a Savoy Theatre performance of The Mikado was heard by up to eight million people. The London Evening Standard noted that this was "probably the largest audience that has ever heard anything at one time in the history of the world."[32] Under Carte, the company continued to make broadcasts during the interwar years. In 1932, The Yeomen of the Guard became the first Gilbert and Sullivan opera to be broadcast in its entirety.[33]

Rebuilding the Savoy Theatre and later years

In 1929 Carte had the 48-year-old Savoy Theatre rebuilt and modernised. It closed on 3 June 1929 and was gutted and completely rebuilt to designs by Frank A. Tugwell with décor by Basil Ionides. The old house had three tiers; the new one had two. The seating capacity (which had decreased to 986 from its original 1,292) was restored nearly completely, to 1,200.[34] The theatre reopened 135 days later on 21 October 1929,[35] with The Gondoliers, designed by Ricketts and conducted by Sargent.[36] The critic Ernest Newman wrote, "I can imagine no gayer or more exhilarating frame for the Gilbert and Sullivan operas than the Savoy as it is now."[37]

Despite its historical connection with Gilbert and Sullivan, most of Carte's London seasons were staged not at the Savoy but at two larger houses: the Prince's (now the Shaftesbury) Theatre (1919–20, 1921–22, 1924, 1926, 1942 and Sadler's Wells (1935, 1936, 1937, 1939, 1947 and 1948).[38] His three Savoy Theatre seasons were in 1929–30, 1932–33, and 1941. In addition to year-round UK tours, Carte mounted tours of North America in 1927, 1928–29, 1934–35, 1936–37, 1939 and 1947–48).[39] During the 1936 tour an American critic wrote, "If there were only some way of keeping them on this side permanently. I humbly suggest to the New Deal that it cancel England's war debt in exchange for the D'Oyly Cartians. We should be much the gainer."[40]

Carte was deeply affected by the death of his son Michael in 1932, discussed below. The actor Martyn Green said, "The heart dropped right out of him. His interest in both the operas and the hotel seemed to fade away."[41] Nevertheless, in 1934 the company made a highly successful eight-month North American tour with Green as its new principal comedian, replacing Henry Lytton.[42] Carte gave approval for, and was closely consulted about, a 1938 film version of The Mikado produced and conducted by Geoffrey Toye, starring Green and released by Universal Pictures,[43][44] but his only new stage production after 1932 was of The Yeomen of the Guard designed in 1939 by Peter Goffin. The re-staging was regarded as radical, but when Goffin took fright at the storm of controversy, Carte told him, "I don't care what they say about the production. I should care if they said nothing."[45]

On 3 September 1939, at the outbreak of World War II, the British government ordered the immediate and indefinite closure of all theatres. Carte cancelled the autumn tour and disbanded the company.[46] Theatres were permitted to reopen from 9 September,[47] but it took some weeks to re-form the company. The company resumed touring in Edinburgh on Christmas Day 1939.[48] It continued to perform throughout the war, but German bombing destroyed the sets and costumes for five of its productions: Cox and Box, The Sorcerer, H.M.S. Pinafore, Princess Ida and Ruddigore. The old productions of Pinafore and Cox and Box were recreated shortly after the war, but the other two operas took longer to rejoin the company's repertory.[49] On the other hand, for the first wartime season, Peter Goffin designed and directed a new production of The Yeomen of the Guard first seen in January 1940, and his new Ruddigore debuted in 1948, shortly after Carte's death. A return of the Company to the U.S. in 1947 was very successful.[42]

Savoy Hotel group

From the beginning of his career, Carte maintained the Savoy group in London, disposing in 1919 of the Grand Hotel, Rome, which his father had acquired in 1896.[50] In the 1920s, he ensured that the Savoy continued to attract a fashionable clientele by a continuous programme of modernisation and the introduction of dancing in the large restaurants. The Savoy Orpheans and the Savoy Havana Band were described by The Times as "probably the best-known bands in Europe".[51] In 1927 Carte appointed his opera company's general manager, Richard Collet, to run the cabaret at the Savoy, which began in April 1929.[52]

Until the 1930s, the Savoy group had not thought it necessary to advertise, but Carte and his manager George Reeves-Smith changed their approach. Reeves-Smith told The Times, "We are endeavouring by intensive propaganda work to get more customers; this work is going on in the U.S.A., in Canada, in the Argentine and in Europe."[53] Towards the end of World War II, Carte added to the Savoy group the bombed-out site near Leicester Square of Stone's Chop House, the freehold of which he purchased with a view to reopening the restaurant there on the lines of the group's Simpson's-in-the-Strand. The revived Stone's reopened after Carte's death.[54]

Personal life

In 1907, Carte married Lady Dorothy Milner Gathorne-Hardy (1889–1977), the third and youngest daughter of the 2nd Earl of Cranbrook, with whom he had a daughter, Bridget, and a son, Michael (1911–1932). Michael was killed at the age of 21 in a motor accident in Switzerland. In 1925, Carte and his wife had a country house built for them in Kingswear, Devon named Coleton Fishacre.[55] The house is still known for its design features and garden with exotic tropical plants.[56] After her parents' divorce, Bridget D'Oyly Carte took over the house, which her father, who lived in London, would visit for long weekends. She sold the house after his death, and it is now owned by the National Trust.[57]

Carte's private pastimes included gardening, notably at Coleton Fishacre, driving and yachting. He was an early devotee of the motor car and incurred the displeasure of the courts more than once. He was fined £3 for driving at 19 miles an hour in 1902,[58] and the following year he was subject to criminal prosecution for knocking down and injuring a child when driving at the speed of 24 miles an hour. He made "every provision for the comfort of the child", who recovered from the accident.[59] In the years after World War I, he was a frequent competitor in yachting races. From 1919 he raced his yacht "Kali" in the Hamble River class.[60] Later, he owned and raced a 19-ton cutter, "Content".[61]

In 1941, Carte divorced his wife for adultery. The suit was undefended.[62] Lady Dorothy moved to the Bahamas and married St Yves de Verteuil, who had been the co-respondent in the divorce case. De Verteuil died in 1963, and Lady Dorothy de Verteuil died in February 1977.[63]

P. G. Wodehouse based the character Psmith, seen in several of his comic novels, on either Rupert D'Oyly Carte or his brother Lucas. In the introduction to his novel Something Fresh, Wodehouse says that Psmith (originally named Rupert, then Ronald) was "based more or less faithfully on Rupert D'Oyly Carte, son of the Savoy theatre man. He was at school with a cousin of mine, and my cousin happened to tell me about his monocle, his immaculate clothes and his habit, when asked by a master how he was, of replying, 'Sir, I grow thinnah and thinnah'."[64] Bridget D'Oyly Carte, however, believed that the Wykehamist schoolboy described to Wodehouse was not her father but his elder brother Lucas, who was also at Winchester College.[65] Rupert D'Oyly Carte was "shy, reserved and at times distinctly taciturn."[66] Psmith, by contrast, is outgoing and garrulous.[67]

Death and legacy

Carte died at the Savoy Hotel, after a brief illness, at the age of 71. A memorial service was held for him at the Savoy Chapel on 23 September 1948.[68] His ashes were scattered on the headland at Coleton Fishacre.[69] He left an estate valued at £228,436.[70] At his death, the family businesses passed to his daughter, Bridget D'Oyly Carte. The Savoy hotel group remained under the control of the Carte family and its associates until 1994.[71] Carte's hotels have remained among the most prestigious in London, with the London Evening Standard calling the Savoy "London's most famous hotel" in 2009.[71] The year after Carte's death, the opera company, which had been the personal possession of Richard and Rupert D'Oyly Carte, became a private company, of which Bridget retained a controlling interest and was chairman and managing director.[72] She inherited a company in strong condition,[73] but the rising costs of mounting professional light opera without any government support eventually became unsustainable, and the company closed in 1982.[74]

The Gilbert and Sullivan operas, nurtured by Carte and his family for over a century, continue to be produced frequently today throughout the English-speaking world and beyond.[24][75][76] By keeping the Savoy operas popular throughout the mid-20th century, Carte continued to influence the course of the development of modern musical theatre.[77][78]

Notes

- ↑ See, for example, Financial Times, 16 August 2008, p. 1; and The Sunday Times, 31 May 2009, p. 23.

- ↑ "The D'Oyly Carte Family" page, at The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive states that Rupert attended Magdalen College, Oxford, but if he did so, he did not graduate, if the above dates, taken from Who's Who, are correct.

- ↑ New York Post, 7 January 1948. The newspaper report states that this was when he was 22, but the first revival of Yeomen was in May 1897, when Rupert D'Oyly Carte was only 20.

- ↑ The Times, 11 May 1949, p. 8.

- ↑ The Times, 7 June 1899, p. 6.

- ↑ Lucas was educated at Winchester College and then Magdalen College, Oxford, and was called to the bar in 1897. He was appointed Private Secretary to Lord Chief Justice Charles Russell in 1899 and died of tuberculosis on 18 January 1907. See Obituary of Lucas D'Oyly Carte, The Times, 22 January 1907, p. 12.

- 1 2 The Times, 21 February 1903, p. 15.

- ↑ Daily Mirror, 10 June 1904, p. 16.

- ↑ Helen had remarried Stanley Boulter, but was generally still known as "Carte" in business.

- ↑ Carte, Bridget D'Oyly. Foreword to Mander, Raymond and Joe Mitchenson, A Picture History of Gilbert and Sullivan, Vista Books, London, 1962.

- ↑ The Times, 1 April 1912, p. 12.

- ↑ The Times, 3 June 1912, p. 11.

- ↑ The Times, 26 May 1913, p. 8.

- ↑ The company toured for ten months per year. Its outer London engagements in these years were in Camden Town, Clapham, Crystal Palace, Deptford, Fulham, Hammersmith, Holloway, Kennington, New Cross, Notting Hill, Peckham, Richmond, Stratford, Wimbledon and Woolwich. See Rollins and Witts.

- ↑ Walbrook, H. M. Chapter 16, Gilbert & Sullivan Opera, A History and a Comment, (1920) London: F. V. White & Co. Ltd.

- ↑ Baily, p. 430; Reprinted in "Rupert D'Oyly Carte's Season ... 1919-20", at The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive, accessed 20 June 2009.

- ↑ Lytton, Henry. Chapter 4, Secrets of a Savoyard (1922), online at The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive, accessed 12 November 2009.

- ↑ Stone, David. J. M. Gordon at Who Was Who in the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company, 27 August 2001, accessed 12 November 2009.

- 1 2 Bettany, Clemence. The D'Oyly Carte Centenary Book, a souvenir book published by the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company during its 1975 centenary season at the Savoy Theatre.

- ↑ During the war, Carte served as a King's Messenger. See Duffey, David. "The D'Oyly Carte Family", The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive, 20 September 2003, accessed 12 November 2009. Baily states that, during the war, "Carte was on special duties in the Navy: he would be sent off on secret journeys to distant parts of the world, and he would mysteriously reappear in London for a few weeks, and when he did so he would put in a few touches to the preparatory work for the rebirth of the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company." Baily, p. 431.

- ↑ The Observer, 24 August 1919, p. 10.

- ↑ Carte's first London season did not include Ruddigore, Utopia, Limited and The Grand Duke.

- ↑ Information about the 1919-20 season at The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive, accessed 20 January 2009. In a last-night speech at the end of the 1924 London season, Carte said that he hoped to revive Utopia, Limited in 1925. See The Times 28 July 1924, p. 10. The opera was not, however, revived until 1975.

- 1 2 Bradley, passim

- ↑ The Times, 10 April 1922, p. 12.

- ↑ The Times 28 May 1945, p. 8. A similar reference in Princess Ida was also altered.

- ↑ Carte, Rupert D'Oyly, The Times, 22 September 1926, p. 8.

- ↑ Recordings of Gilbert and Sullivan songs had been made as early as the 1890s (Joseph, p. 220), and there were several complete or nearly-complete operas recorded in the early years of the twentieth century, not under D'Oyly Carte auspices.

- ↑ Shepherd, Marc. "The First D'Oyly Carte Recordings", A Gilbert and Sullivan Discography, 18 November 2001, accessed 21 November 2009.

- ↑ Shepherd, Marc. "The D'Oyly Carte Complete Electrical Sets", A Gilbert and Sullivan Discography, 18 November 2001, accessed 21 November 2009.

- ↑ Rollins and Witts, pp. XI–XII.

- ↑ Reid, p. 137.

- ↑ Webster, Chris. "Original D'Oyly Carte Broadcasts", A Gilbert and Sullivan Discography, 16 July 2005, accessed 22 November 2009.

- ↑ The Times, 21 October 1929.

- ↑ Savoy Theatre programme note, September 2000.

- ↑ Information about the 1929-20 season and the new designs, The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive, accessed 12 November 2009.

- ↑ quoted in Baily, p. 442.

- ↑ Rollins and Witts, pp. 136–72

- ↑ Rollins and Witts, pp. 153–72

- ↑ The Philadelphia Public Ledger, quoted in Baily, p. 440.

- ↑ Joseph, p. 219, quoting Martyn Green.

- 1 2 Wilson and Lloyd, p. 128.

- ↑ Baily, p. 446.

- ↑ Shepherd, Marc. "The Technicolor Mikado Film (1939)", A Gilbert and Sullivan Discography (2001), accessed 20 November 2009.

- ↑ Baily, p. 19.

- ↑ Joseph, p. 246.

- ↑ The Times, 9 September 1939, p. 9.

- ↑ Rollins and Witts, p. 164.

- ↑ Pinafore re-entered the repertory in July 1947, Cox and Box in the 1947–48 season, Ruddigore in November 1948, and Princess Ida in September 1954 (see Rollins and Witts, pp. 171-79 and VII-VIII). The Sorcerer was not revived until April 1971 (see The Times, 2 April 1971, p. 10).

- ↑ The Times, 15 July 1896, p. 4; and 20 December 1919, p. 18.

- ↑ The Times, 29 March 1924, p. 20.

- ↑ The Times, 27 March 1929, p. 23.

- ↑ The Times, 27 March 1931, p. 22; and 22 April 1932, p. 20.

- ↑ The Times, 5 April 1946, p. 9; and 14 October 1963, p. 16.

- ↑ "Coleton Fishacre", National Trust, accessed 5 August 2016

- ↑ See the Country Life magazine, 25 October 2007 feature on the house and gardens.

- ↑ Coleton Fishacre House and Garden, Nationaltrust.org, accessed 5 January 2010.

- ↑ The Times, 3 November 1902, p. 6.

- ↑ The Times, 24 November 1903, p. 11.

- ↑ See, for example, The Times, 22 July 1919, p. 5; and 11 August 1919, p. 5.

- ↑ The Times, 19 August 1927, p. 4.

- ↑ The Times, 18 December 1941, p. 8.

- ↑ The Times, 16 March 1977, p. 18.

- ↑ The Psmith novels include Mike (1909), Psmith in the City (1910), Psmith, Journalist (1915) and Leave it to Psmith (1923)

- ↑ Donaldson, p. 85.

- ↑ Joseph, p. 160.

- ↑ "Don't talk so much! I never met a fellow like you for talking!" – Wodehouse, Leave it to Psmith, quoted in Usborne, p. 94.

- ↑ "Our London Correspondence", The Manchester Guardian, 23 September 1948.

- ↑ Kennedy, Maev. "An ideal cove", The Guardian, 15 May 1999, p. G7.

- ↑ The Times, 6 October 1948, p. 7.

- 1 2 Prynn, Jonathan. "Savoy 'up for sale' as Saudi owner's billions dwindle", 16 April 2009.

- ↑ The Times, 24 March 1949, p. 2.

- ↑ Joseph, pp. 273–74.

- ↑ Joseph, p. 358.

- ↑ List of 200 amateur G&S performing groups at The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive, accessed 1 November 2009.

- ↑ Lee, Bernard. "Gilbert and Sullivan are still going strong after a century", Sheffield Telegraph, 1 August 2008.

- ↑ Bargainnier, Earl F. "W. S. Gilbert and American Musical Theatre", pp. 120–33, American Popular Music: Readings from the Popular Press by Timothy E. Scheurer, Popular Press, 1989 ISBN 0-87972-466-8.

- ↑ Jones, J. Bush. Our Musicals, Ourselves, pp. 10–11, 2003, Brandeis University Press: Lebanon, N.H. (2003) ISBN 1-58465-311-6.

References

- Baily, Leslie (1956). The Gilbert and Sullivan Book. London: Cassel & Co.

- Bettany, Clemence (1975). D'Oyly Carte Centenary. London: D'Oyly Carte Opera Company.

- Bradley, Ian (2005). Oh Joy! Oh Rapture! The Enduring Phenomenon of Gilbert and Sullivan. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-516700-7.

- Current Biography. New York: H W Wilson Co. 1948.

- Donaldson, Frances (1983). P G Wodehouse. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. ISBN 0-7088-2356-4.

- Green, Martyn (1952). Here's a How-de-do. New York: W. W. Norton & Co.

- Jones, Brian (2005). Lytton, Gilbert and Sullivan's Jester. London: Trafford Publishing.

- Joseph, Tony (1994). D'Oyly Carte Opera Company, 1875–1982: An Unofficial History. London: Bunthorne Books. ISBN 0-9507992-1-1.

- Morrell, Roberta (1999). Kenneth Sandford: 'Merely Corroborative Detail'. Leicester: Scotia Press. ISBN 1-4251-7829-4.

- Reid, Charles (1968). Malcolm Sargent: a biography. London: Hamish Hamilton Ltd. ISBN 0-241-91316-0.

- Rollins, Cyril; R. John Witts (1962). The D'Oyly Carte Opera Company in Gilbert and Sullivan Operas. London: Michael Joseph Ltd.

- Usborne, Richard (1978). Wodehouse at Work to the End'. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-004564-3.

- Who Was Who, Vol IV, 1941-50. London: A & C Black. 1952.

- Who's Who in the Theatre, 10th edition. London: Sir Isaac Pitman & Sonsck. 1947.

External links

- Article on Carte family

- D'Oyly Carte Opera Company Website

- Simpson's-in-the-Strand

- The Berkeley

- Claridge's