Barasingha

| Barasingha | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Cervidae |

| Genus: | Rucervus |

| Species: | R. duvaucelii |

| Binomial name | |

| Rucervus duvaucelii[2] (G. Cuvier, 1823) | |

| |

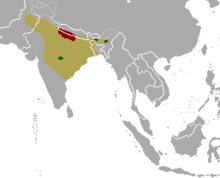

| Historic range (yellow); relict populations: duvaucelii (red); branderi (green); ranjitsinhi (blue) | |

The barasingha (Rucervus duvaucelii syn. Cervus duvaucelii), also called swamp deer, is a deer species distributed in the Indian subcontinent. Populations in northern and central India are fragmented, and two isolated populations occur in southwestern Nepal. It is extinct in Pakistan and in Bangladesh.[1]

The specific name commemorates the French naturalist Alfred Duvaucel.[3]

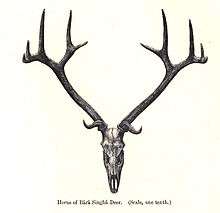

The swamp deer differs from all the Indian deer species in that the antlers carry more than three tines. Because of this distinctive character it is designated barasingha, meaning "twelve-tined."[4] Mature stags have 10 to 14 tines, and some have been known to have up to 20.[5]

In Assamese, barasingha is called dolhorina; dol meaning swamp. In central India, it is called goinjak (stags) or gaoni (hinds).

Characteristics

The barasingha is a large deer with a shoulder height of 44 to 46 in (110 to 120 cm) and a head-to-body length of nearly 6 ft (180 cm). Its hair is rather woolly and yellowish brown above but paler below, with white spots along the spine. The throat, belly, inside of the thighs and beneath the tail is white. In summer the coat becomes bright rufous-brown. The neck is maned. Females are paler than males. Young are spotted. Average antlers measure 30 in (76 cm) round the curve with a girth of 5 in (13 cm) at mid beam.[6] A record antler measured 104.1 cm (41.0 in) round the curve.[5]

Stags weigh 170 to 280 kg (370 to 620 lb). Females are less heavy, weighing about 130 to 145 kg (287 to 320 lb).[7] Large stags have weighed from 460 to 570 lb (210 to 260 kg).[4]

Distribution and habitat

In the 19th century, swamp deer ranged along the base of the Himalayas from Upper Assam to the west of the Jumna River, throughout Assam, in a few places in the Indo-Gangetic plain from the Eastern Sundarbans to Upper Sind, and locally throughout the area between the Ganges and Godavari as far east as Mandla. Swamp deer was also common in parts of the Upper Nerbudda valley and to the south in Bastar.[6] They frequent flat or undulating grasslands and generally keep in the outskirts of forests. Sometimes, they are also found in open forest.[4]

In the 1960s, the total population was estimated at 1,600 to less than 2,150 individuals in India and about 1,600 in Nepal. Today, the distribution is much reduced and fragmented due to major losses in the 1930s–1960s following unregulated hunting and conversion of large tracts of grassland to cropland. Swamp deer occur in the Kanha National Park of Madhya Pradesh, in 2 localities in Assam, and in only 6 localities in Uttar Pradesh. They are regionally extinct in West Bengal.[8] They are also probably extinct in Arunachal Pradesh.[9] A few survive in Assam's Kaziranga and Manas National Parks.[10][11][12][13]

Distribution of subspecies

Three subspecies are currently recognized:[14]

- Western swamp deer R. d. duvauceli (Cuvier, 1823) – has splayed hooves and is adapted to the flooded tall grassland habitat in the Indo-Gangetic plain;[15] in the early 1990s, populations in India were estimated at 1,500–2,000 individuals, and 1,500–1,900 individuals in the Sukla Phanta Wildlife Reserve of Nepal;[8] latter population reached 2,170 individuals including 385 fawns in spring 2013.[16]

- Southern swamp deer R. d. branderi (Pocock 1943) – has hard hooves and is adapted to hard ground in open sal forest with a grass understorey;[15] survives only in the Kanha National Park, where the population numbered about 500 individuals in 1988; 300–350 individuals were estimated at the turn of the century;[8]

- Eastern swamp deer R. d. ranjitsinhi (Grooves 1982) – is only found in Assam, where the population numbered about 700 individuals in 1978; 400–500 individuals were estimated in Kaziranga National Park at the turn of the century.[8]

Ecology and behaviour

Swamp deer are mainly grazers.[4] They largely feed on grasses and aquatic plants, foremost on Saccharum, Imperata cylindrica, Narenga porphyrocoma, Phragmites karka, Oryza rufipogon, Hygroryza and Hydrilla. They feed throughout the day with peaks during the mornings and late afternoons to evenings. In winter and monsoon, they drink water twice, and thrice or more in summer. In the hot season, they rest in the shade of trees during the day.[8]

In central India, the herds comprise on average about 8–20 individuals, with large herds of up to 60. There are twice as many females than males. During the rut they form large herds of adults. The breeding season lasts from September to April, and births occur after a gestation of 240–250 days in August to November. The peak is in September and October in Kanha National Park.[7] They give birth to single calves.

When alarmed, they give out shrill, baying alarm calls.[5]

Captive specimens live up to 23 years.

Threats

Swamp deer lost most of its ancestral range because wetlands were converted and used for agriculture so that their habitat was reduced to small and isolated fragments. The remaining habitat in protected areas is threatened by the change in river dynamics, reduced water flow during summer, increasing siltation, and further degraded by local people who cut grass, timber and fuelwood. The swamp deer populations outside protected areas and seasonally migrating populations are threatened by poaching for antlers and meat, which are sold in local markets.[8]

George Schaller wrote: "Most of these remnants have or soon will have reached the point of no return."[7]

Conservation

Rucervus duvaucelii is listed on CITES Appendix I.[1] In India, it is included under Schedule I of the Wildlife Protection Act of 1972.[8]

In captivity

In 1992, there were about 50 individuals in five Indian zoos and 300 in various zoos in North America and Europe.[8]

Swamp deer were introduced to Texas.[17] Sport hunters for whom bagging a stag with huge antlers with as many points as possible is a novelty, pay about $4,000 as trophy fees for hunting a swamp deer.

In culture

Rudyard Kipling in The Second Jungle Book featured a barasingha in the chapter "The Miracle of Purun Bhagat" by the name of "barasingh". It befriends Purun Bhagat because the man rubs the stag's velvet off his horns. Purun Bhagat then gives the barasinga nights in the shrine at which he is staying, with his warm fire, along with a few fresh chestnuts every now and then. Later as pay, the stag warns Purun Bhagat and his town about how the mountain on which they live is crumbling.

Barasingha is the state animal of the Indian state of Madhya Pradesh.[18]

References

- 1 2 3 Duckworth, J. W.; Kumar, N.S.; Pokharel, C.P.; Baral, H. S.; Timmins, R. J. (2015). "Rucervus duvaucelii". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2016.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature.

- ↑ Grubb, P. (2005). "Order Artiodactyla". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 668–669. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ↑ Cuvier, G. (1823). Recherches sur les ossemens fossiles de quadrupèdes. Nouvelle édition, Tome Quatrième. Dufour & d'Ocagne, Paris, Amsterdam.

- 1 2 3 4 Lydekker, R. (1888–1890). The new natural history Volume 2. Printed by order of the Trustees of the British Museum (Natural History), London.

- 1 2 3 Prater, S. H. (1948). The book of Indian animals. Oxford University Press. (10th ed.)

- 1 2 3 Blanford, W. T. (1888–1891). The fauna of British India, including Ceylon and Burma. Mammalia. Taylor and Francis, London.

- 1 2 3 Schaller, G. B. (1967). The Deer and the Tiger – A Study of Wildlife in India. University Chicago Press, Chicago, IL, USA.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Qureshi, Q., Sawarkar, V. B., Rahmani, A. R. and Mathur, P. K. (2004). Swamp Deer or Barasingha (Cervus duvauceli Cuvier, 1823). Envis Bulletin 7: 181–192.

- ↑ Choudhury, A. U. (2003). The mammals of Arunachal Pradesh. Regency Publications, New Delhi ISBN 8187498803.

- ↑ Choudhury, A. U. (1997). Checklist of the mammals of Assam. 2nd ed. Gibbon Books & Assam Science Technology & Environment Council, Guwahati, India. ISBN 81-900866-0-X

- ↑ Choudhury, A. U. (2004). Kaziranga: Wildlife in Assam. Rupa & Co., New Delhi.

- ↑ Choudhury, A. U. (1987). "Railway threat to Kaziranga" (PDF). Oryx. 21 (3): 160–163. doi:10.1017/S0030605300026892.

- ↑ Choudhury, A. U. (1986). Manas Sanctuary threatened by extraneous factors. The Sentinel.

- ↑ Groves, C. (1982). "Geographic variation in the Barasingha or Swamp Deer (Cervus duvauceli)". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 79: 620–629.

- 1 2 Pocock R. (1943). The larger deer of British India. Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society 43: 553–572.

- ↑ The Himalayan Times (2013). Shuklaphanta sees increase swamp deer number. Kanchanpur, 19 April 2013.

- ↑ McCarthy, A., Blouch, R., Moore, D., and Wemmer, C. M. (1998). Deer: status survey and conservation action plan IUCN Deer Specialist Group. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland.

- ↑ http://www.pannatigerreserve.in/kids/state.htm

Further reading

- M. Acharya, M. Barad, S. Bhalani, P. Bilgi, M. Panchal, V. Shrimali, W. Solanki, D.M. Thumber. Kanha Chronicle. Centre for Environment Education, Ahmedabad in collaboration with the United States National Park Service.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1905 New International Encyclopedia article Swamp Deer. |