Rotator cuff

| Rotator cuff | |

|---|---|

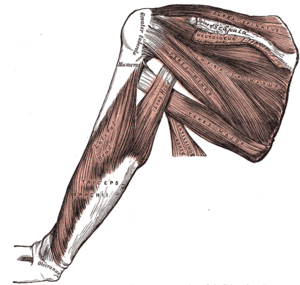

Muscles on the dorsum of the scapula, and the triceps brachii. | |

The scapular and circumflex arteries (posterior view). | |

In anatomy, the rotator cuff (sometimes incorrectly called a "rotator cup", "rotor cuff", or "rotary cup"[1]) is a group of muscles and their tendons that act to stabilize the shoulder. The four muscles of the rotator cuff are over half of the seven scapulohumeral muscles. The four muscles are the supraspinatus muscle, the infraspinatus muscle, teres minor muscle, and the subscapularis muscle.

Structure

Muscles composing rotator cuff

| Muscle | Origin on scapula | Attachment on humerus | Function | Innervation |

| Supraspinatus muscle | supraspinous fossa | superior [2] facet of the greater tubercle | abducts the humerus | Suprascapular nerve (C5) |

| Infraspinatus muscle | infraspinous fossa | posterior facet of the greater tubercle | externally rotates the humerus | Suprascapular nerve (C5-C6) |

| Teres minor muscle | middle half of lateral border | inferior facet of the greater tubercle | externally rotates the humerus | Axillary nerve (C5) |

| Subscapularis muscle | subscapular fossa | lesser tubercle | internally rotates the humerus | Upper and Lower subscapular nerve (C5-C6) |

The supraspinatus muscle fans out in a horizontal band to insert on the superior and middle facets of the greater tubercle. The greater tubercle projects as the most lateral structure of the humeral head. Medial to this, in turn, is the lesser tuberosity of the humeral head. The subscapularis muscle origin is divided from the remainder of the rotator cuff origins as it is deep to the scapula.

The four tendons of these muscles converge to form the rotator cuff tendon. These tendinous insertions along with the articular capsule, the coracohumeral ligament, and the glenohumeral ligament complex, blend into a confluent sheet before insertion into the humeral tuberosities.[3] The insertion site of the rotator cuff tendon at the greater tuberosity is often referred to as the footprint. The infraspinatus and teres minor fuse near their musculotendinous junctions, while the supraspinatus and subscapularis tendons join as a sheath that surrounds the biceps tendon at the entrance of the bicipital groove.[3] The supraspinatus is most commonly involved in a rotator cuff tear.

Function

The rotator cuff muscles are important in shoulder movements and in maintaining glenohumeral joint (shoulder joint) stability.[4] These muscles arise from the scapula and connect to the head of the humerus, forming a cuff at the shoulder joint. They hold the head of the humerus in the small and shallow glenoid fossa of the scapula. The glenohumeral joint has been analogously described as a golf ball (head of the humerus) sitting on a golf tee (glenoid fossa).[5]

During abduction of the arm, moving it outward and away from the trunk, the rotator cuff compresses the glenohumeral joint, a term known as concavity compression, in order to allow the large deltoid muscle to further elevate the arm. In other words, without the rotator cuff, the humeral head would ride up partially out of the glenoid fossa, lessening the efficiency of the deltoid muscle. The anterior and posterior directions of the glenoid fossa are more susceptible to shear force perturbations as the glenoid fossa is not as deep relative to the superior and inferior directions. The rotator cuff's contributions to concavity compression and stability vary according to their stiffness and the direction of the force they apply upon the joint.

In addition to stabilizing the glenohumeral joint and controlling humeral head translation, the rotator cuff muscles also perform multiple functions, including abduction, internal rotation, and external rotation of the shoulder. The infraspinatus and subscapularis have significant roles in scapular plane shoulder abduction (scaption), generating forces that are two to three times greater than the force produced by the supraspinatus muscle.[6] However, the supraspinatus is more effective for general shoulder abduction because of its moment arm.[7] The anterior portion of the supraspinatus tendon is submitted to significantly greater load and stress, and performs its mainfunctional role.[8]

Clinical significance

Rotator cuff tear

The tendons at the ends of the rotator cuff muscles can become torn, leading to pain and restricted movement of the arm. A torn rotator cuff can occur following a trauma to the shoulder or it can occur through the "wear and tear" on tendons, most commonly the supraspinatus tendon found under the acromion.

Rotator cuff injuries are commonly associated with motions that require repeated overhead motions or forceful pulling motions. Such injuries are frequently sustained by athletes whose actions include making repetitive throws, athletes such as baseball pitchers, softball pitchers, American football players (especially quarterbacks), cheerleaders, weightlifters (especially powerlifters due to extreme weights used in the bench press), rugby players, volleyball players (due to their swinging motions), water polo players, rodeo team ropers, shot put throwers (due to using poor technique), swimmers, boxers, kayakers, western martial artists, fast bowlers in cricket, tennis players (due to their service motion) and tenpin bowlers due to the repetitive swinging motion of the arm with the weight of a bowling ball. This type of injury also commonly affects orchestra conductors, choral conductors, and drummers (due, again, to swinging motions).

After experiencing a rotator cuff tear, minimally invasive surgery is needed in order to repair the torn tendon. After surgery, the rehabilitation of the rotator cuff is necessary in order to regain maximum strength and range of motion within the shoulder joint.[9] Physical therapy progresses through four stages, increasing movement throughout each phase. The tempo and intensity of the stages are solely reliant on the extent of the injury and the patient’s activity necessities.[10] The first stage requires immobilization of the shoulder joint. The shoulder that is injured is placed in a sling and shoulder flexion or abduction of the arm is avoided for 4 to 6 weeks after surgery (Brewster, 1993). Avoiding movement of the shoulder joint allows the torn tendon to fully heal.[9] Once the tendon is entirely recovered, passive exercises can be implemented. Passive exercises of the shoulder are movements in which a physical therapist maintains the arm in a particular position, manipulating the rotator cuff without any effort by the patient.[11] These exercises are used to increase stability, strength and range of motion of the Subscapularis, Supraspinatus, Infraspinatus, and Teres minor muscles within the rotator cuff.[11] Passive exercises include internal and external rotation of the shoulder joint, as well as flexion and extension of the shoulder.[11]

As progression increases after 4–6 weeks,active exercises are now implemented into the rehabilitation process. Active exercises allow an increase in strength and further range of motion by permitting the movement of the shoulder joint without the support of a physical therapist.[12] Active exercises include the Pendulum exercise (as shown in Image 2), which is used to strengthen the Supraspinatus, Infraspinatus, and Subscapularis.[12] External rotation of the shoulder with the arm at a 90-degree angle is an additional exercise done to increase control and range of motion of the Infraspinatus and Teres minor muscles. Various active exercises are done for an additional 3–6 weeks as progress is based on an individual case by case basis.[12] At 8–12 weeks, strength training intensity will increase as free-weights and resistance bands will be implemented within the exercise prescription.[6]

Rotator cuff impingement

A systematic review of relevant research found that the accuracy of the physical examination is low.[13] The Hawkins-Kennedy test[14][15] has a sensitivity of approximately 80% to 90% for detecting impingement. The infraspinatus and supraspinatus[16] tests have a specificity of 80% to 90%.[13]

Rotator interval inflammation and fibrosis

The rotator interval is a triangular space in the shoulder that is functionally reinforced externally by the coracohumeral ligament and internally by the superior glenohumeral ligament, and traversed by the intra-articular biceps tendon. On imaging, it is defined by the coracoid process at its base, the supraspinatus tendon superiorly and the subscapularis tendon inferiorly. Changes of adhesive capsulitis can be seen at this interval as edema and fibrosis. Pathology at the interval is also associated with glenohumeral and biceps instability.[17]

Pain management

The rotator cuff includes muscles such as the supraspinatus muscle, the infraspinatus muscle, the teres minor muscle and the subscapularis muscle. The upper arm consists of the deltoids, biceps, as well as the triceps. Steps must be taken and precautions need to be made in order for the rotator cuffs to heal properly following surgery while still maintaining function to prevent any deteriorating effects on the muscles. In the immediate postoperative period (within one week following surgery), pain can be treated with a standard ice wrap. There are also commercial devices available which not only cool the shoulder but also exert pressure on the shoulder ("compressive cryotherapy"). However, one study has shown no significant difference in postoperative pain when comparing these devices to a standard ice wrap.[18]

Continuous passive motion

Physiotherapy can help manage the pain, but utilizing a program that involves continuous passive motion will reduce the pain even further. Assisted passive motion at a low intensity allows the tissues to be stretched slightly without damaging them [19] Continuous passive motion improves the shoulder range and enables the subject to expand their range of motion without experiencing additional pain. Easing into the motions will allow the person to continue working those muscles to keep them from undergoing atrophy, while also still maintaining that minimum level of function where daily function is allowed. Doing these exercises will also prevent tears in the muscles that will impair daily function further.[19] Since injuries of the rotator cuff often tend to inhibit motion without first experience discomfort and pain, other methods can be done to help accommodate that.

Capsular release

A surgery procedure exists where the joint of the injured area will be freed in order to achieve a full range of motion without too much pain and discomfort, speeding up recovery time and allowing the person to better perform optimally. A study conducted by Jin-Young Park investigated the benefits of using capsular release to help relieve the stiffness of the shoulders that usually come whenever there is an injury in the rotator cuff. Some of the subjects had diabetes mellitus, which can also cause shoulder stiffness, impeding external rotation of the shoulders. Of the 49 subjects recruited for this trial, 21 of them went through only manipulation to relieve stiffness, while the other 28 underwent a capsular release surgery along with the manipulation to treat shoulder stiffness. Despite the results that suggest that there appears to be no difference in external rotation between the control and treatment group, the subjects that had diabetes mellitus benefitted most from the treatment that included the capsular release surgery.[20] Their flexion improved significantly in both forward flexion and external rotation in a short amount of time compared to the subjects that were not diagnosed with diabetes mellitus.

Orthotherapy exercises

Patients that suffer from pain in the rotator cuff may consider utilizing orthotherapy into their daily lives. Orthotherapy is an exercise program that aims to restore the motion and strength of the shoulder muscles.[21] Patients can go through the three phases of orthotherapy to help manage pain and also recover their full range of motion in the rotator cuff. The first phase involves gentle stretches and passive all around movements, and people are advised not to go above 70 degrees of elevation to prevent any kind of further pain.[21] The second phase of this regimen requires patients to implement exercises to strengthen the muscles that are surrounding the rotator cuff muscles, combined with the passive exercises done in the first phase to keep on stretching the tissues without overexerting them. Exercises include pushups and shoulder shrugs, and after a couple of weeks of this, daily activities are gradually added to the patient’s routine. This program does not require any sort of medication or surgery and can serve as a good alternative. The rotator cuff and the upper muscles are responsible for many daily tasks that people do in their lives. A proper recovery needs to be maintained and achieved to prevent limiting movement, and can be done through simple movements.

Additional images

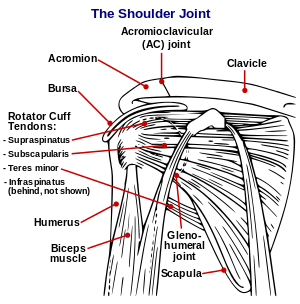

Diagram of the human shoulder joint

Diagram of the human shoulder joint Suprascapular and axillary nerves of right side, seen from behind.

Suprascapular and axillary nerves of right side, seen from behind. The suprascapular, axillary, and radial nerves.

The suprascapular, axillary, and radial nerves.

See also

References

- ↑ Hartman, B.; Robertson, M. "Push-Ups, Face Pulls, and Shrugs ...for Strong and Healthy Shoulders!". Tnation.

The rotator cuff, of course. (Or for those of you from Indiana, that would be your "rotary cup"

- ↑ Grays Anatomy 40th

- 1 2 Matava MJ, Purcell DB, Rudzki JR (2005). "Partial-thickness rotator cuff tears". Am J Sports Med. 33 (9): 1405–17. doi:10.1177/0363546505280213. PMID 16127127.

- ↑ Morag Y, Jacobson JA, Miller B, De Maeseneer M, Girish G, Jamadar D (2006). "MR imaging of rotator cuff injury: what the clinician needs to know". Radiographics. 26 (4): 1045–65. doi:10.1148/rg.264055087. PMID 16844931.

- ↑ Khazzam M, Kane SM, Smith MJ (2009). "Open shoulder stabilization procedure using bone block technique for treatment of chronic glenohumeral instability associated with bony glenoid deficiency" (PDF). Am J. Orthop. 38 (7): 329–35. PMID 19714273.

- 1 2 Escamilla RF, Yamashiro K, Paulos L, Andrews JR (2009). "Shoulder muscle activity and function in common shoulder rehabilitation exercises". Sports Med. 39 (8): 663–85. doi:10.2165/00007256-200939080-00004. PMID 19769415.

- ↑ Arend, C.F. (2013). "01.1 Rotator Cuff: Anatomy and Function". Ultrasound of the Shoulder. Master Medical Books. ShoulderUS.com]

- ↑ Itoi E, Berglund LJ, Grabowski JJ, Schultz FM, Growney ES, Morrey BF, An KN (1995). "Tensile properties of the supraspinatus tendon". J. Orthop. Res. 13 (4): 578–84. doi:10.1002/jor.1100130413. PMID 7674074.

- 1 2 Brewster C, Schwab DR (1993). "Rehabilitation of the shoulder following rotator cuff injury or surgery". J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 18 (2): 422–6. doi:10.2519/jospt.1993.18.2.422. PMID 8364597.

- ↑ Kuhn JE (2009). "Exercise in the treatment of rotator cuff impingement: a systematic review and a synthesized evidence-based rehabilitation protocol". J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 18 (1): 138–60. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2008.06.004. PMID 18835532.

- 1 2 3 Waltrip RL, Zheng N, Dugas JR, Andrews JR (2003). "Rotator cuff repair. A biomechanical comparison of three techniques". Am J Sports Med. 31 (4): 493–7. PMID 12860534.

- 1 2 3 Jobe FW, Moynes DR (1982). "Delineation of diagnostic criteria and a rehabilitation program for rotator cuff injuries". Am J Sports Med. 10 (6): 336–9. doi:10.1177/036354658201000602. PMID 7180952.

- 1 2 Hegedus EJ, Goode A, Campbell S, et al. (February 2008). "Physical examination tests of the shoulder: a systematic review with meta-analysis of individual tests". British Journal of Sports Medicine. 42 (2): 80–92. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2007.038406. PMID 17720798.

- ↑ ShoulderDoc.co.uk Shoulder & Elbow Surgery. "Hawkins-Kennedy Test". Retrieved 2007-09-12. (video)

- ↑ Brukner P, Khan K, Kibler WB. "Chapter 14: Shoulder Pain". Retrieved 2007-08-30.

- ↑ ShoulderDoc.co.uk Shoulder & Elbow Surgery. "Empty Can/Full Can Test". Retrieved 2007-09-12. (video)

- ↑ Petchprapa, CN; Beltran, LS; Jazrawi, LM; Kwon, YW; Babb, JS; Recht, MP (September 2010). "The rotator interval: a review of anatomy, function, and normal and abnormal MRI appearance.". AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 195 (3): 567–76. doi:10.2214/ajr.10.4406. PMID 20729432.

- ↑ Kraeutler, MJ; Reynolds, KA; Long, C; McCarty, EC (Jun 2015). "Compressive cryotherapy versus ice-a prospective, randomized study on postoperative pain in patients undergoing arthroscopic rotator cuff repair or subacromial decompression". Journal of Shoulder & Elbow Surgery. 24 (6): 854–859. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2015.02.004. PMID 25825138.

- 1 2 Plessis, M. Du, E. Eksteen, A. Jenneker, E. Kriel, C. Mentoor, T. Stucky, D. Van Staden, and L. Morris. "The Effectiveness of Continuous Passive Motion on Range of Motion, Pain and Muscle Strength following Rotator Cuff Repair: A Systematic Review." Clinical Rehabilitation (2011): 291-302

- ↑ Park, J.-Y., S. W. Chung, Z. Hassan, J.-Y. Bang, and K.-S. Oh. "Effect of Capsular Release in the Treatment of Shoulder Stiffness Concomitant With Rotator Cuff Repair: Diabetes as a Predisposing Factor Associated With Treatment Outcome." The American Journal of Sports Medicine (2014): 840-50. SagePub

- 1 2 Wirth, Michael A., Carl Basamania, and Charles A. Rockwood. "Nonoperative Management Of Full-Thickness Tears Of The Rotator Cuff." Orthopedic Clinics of North America (1997): 59-67