Catholic Church in Belgium

The Catholic Church in Belgium, part of the global Catholic Church, is under the spiritual leadership of the Pope, the curia in Rome and the Conference of Belgian Bishops.

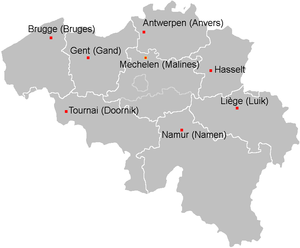

Dioceses

There are eight dioceses, including one archdiocese, seat of the archiepiscopal residence and St. Rumbolds Cathedral, located in the old Flemish city of Mechelen (Malines in French). Since 2010, the archbishop of Mechelen and primate of all Belgium is Archbishop André-Joseph Léonard.[1]

| Archdiocese / diocese | Est.[2] | Cathedral[2] | Co-cathedral | Weblink |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Archdiocese of Mechelen | 1559 | Cathedral of St. Rombald | Cathedral of St. Michael and St. Gudula | |

| Diocese of Antwerp | 1961 | Cathedral of Our Lady | ||

| Diocese of Bruges | 1834 | Cathedral of the Saviour and St. Donat | ||

| Diocese of Ghent | 1559 | Cathedral of St. Bavo | ||

| Diocese of Hasselt | 1967 | St. Quentin Cathedral | ||

| Diocese of Liège | 720 | Cathedral of St. Lambert | ||

| Diocese of Namur | 1559 | Cathedral of St. Alban | ||

| Diocese of Tournai | 450 | Cathedral of Our Lady of Tournai |

The Belgian church established and sponsors the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven and the Université catholique de Louvain, which together comprise the largest university in Belgium. It is considered one of the "World's Best Colleges and Universities" in the new 2009 US News and World Report. The archbishop of Mechelentis ex officio the Great Chancellor of the university. It was founded by the bishops of Belgium in 1834 to replace the Old University of Leuven, which the French Republic had suppressed in 1797. Some of its most notable graduates include Georges Lemaître, priest, astronomer, and proposer of the Big Bang theory, Otto von Habsburg, former head of the Habsburg family, Saint Alberto Hurtado, Chilean Jesuit priest who was canonised in 2005, Charles Jean de la Vallée-Poussin, mathematician who proved the prime number theorem, Christian de Duve, winner of the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1974, among others. The Belgian church also oversees the Basilica of the Sacred Heart, the National Basilica of Belgium.

Demographics

| Catholics in Belgium | ||||||||||

| year | Sunday Mass Attendance [3] (%) | baptism (%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1967 | 42.9% | 93.6% | ||||||||

| 1973 | 32.3% | 89.3% | ||||||||

| 1980 | 26.7% | 82.4% | ||||||||

| 1985 | 22.0% | - | ||||||||

| 1990 | 17.9% | 75.0% | ||||||||

| 1995 | 13.1% | - | ||||||||

| 1998 | 11.2% | 64.7% | ||||||||

| 2006 | 7% (Flanders only)[4] | 56.8% | ||||||||

| 2009 | 5%[5] | |||||||||

Over 75% of Belgians are Roman Catholic.[6] However, as elsewhere in Northwest Europe, secularisation has hit hard in Belgium; Sunday church attendance has dropped well below 10% as per latest research such as from the "Centrum voor politicologie" of the Catholic University Leuven.[7] Although sources are quoting different figures between 4 and 9%, a church attendance of 6% in 2009 seems to be the most likely figure. Sources are quoting a drop in attendance of 0,5% yearly and in 1998 (the last year during which mass attendance was measured), attendance was just above 11%. Early 2008, the Belgian Catholic Church has announced it will gather and publish adherence figures though the current usual Sunday attendance statistics does not seem to bother Cardinal Danneels, who said he was more concerned with the declining number of new priests.[8]

As of 2010, there are about 1900 priests in the archdiocese of Malines-Brussels, but most of them are either retired or on the verge of retirement. Only two were ordained in 2007.[8]

In 2009, Cardinal Andre-Mutien Leonard was appointed Belgium's new primate, but only after the 450th anniversary celebration of the Mechelen-Brussels archdiocese and the canonisation of Fr. Damien De Veuster of Molokai. Both events were led by Cardinal Godfried Danneels. Before his appointment, Leonard was Bishop of Namur.[9]

Clerical sex abuse scandal

Like several other countries since the mid-1990s, Belgium has been affected by a clerical sex abuse scandal. Priests have been found guilty of sexual conduct with minors.[10][11] A commission received about 500 reports from alleged victims and cited 320 alleged abusers, of whom 102 were known to have been clergy members from 29 congregations.[12] Thirteen of the alleged victims committed suicide.[12]

The scandal came to a head when Roger Vangheluwe, Bishop of Bruges, resigned in April 2010 after allegedly admitting that he had sexually abused a boy in his "close entourage”. The boy was not named. The acts remain undisclosed. No criminal charges have been brought against Vangheluwe, who has since retired to a Trappist monastery in Westvleteren, in Western Belgium, though he may be asked to leave after growing public pressure.[13] [14][15]

Vangheluwe's resignation followed the jailing of Robert Borremans, a popular Brussels priest who had officiated at the marriage of the prince and princess of Belgium. Borremans was arrested in 2006, and in January 2010 he was convicted of sexual conduct with two boys over a period of seven years. The boys were 6 and 11 years old when the abuse began in 1994, and the acts cited included touching, masturbation and fellatio. Borremans denied the criminal charges in one of the cases, stating that the acts were consensual and occurred when the victim was not a minor. He was found guilty based on the victims' testimony, supported by expert opinion.[16][17][18]

Vangheluwe's resignation came at a time of increased media coverage of clerical sex abuse in Europe. After the resignation, the Catholic Church launched an investigating commission into allegations of clerical child abuse in Belgium, headed by the independent psychologist Peter Adriaenssens. The commission's work came to an abrupt end on 24 June 2010, when the Belgian police raided the offices of the Catholic Church in Belgium and sealed them. There were four raids in all, with thousands of documents seized. One of the raids involved drilling into the tombs of two cardinals. The Vatican was reported as being 'indignant' over the raids, saying they had led to the "violation of confidentiality of precisely those victims for whom the raids were carried out".[14][19][20]

Nonetheless, the Adriaenssens commission published a 200-page report on 10 September 2010. According to the report, the commission heard allegations from 488 complainants, concerning incidents that took place between 1950 and 1990. The report contained testimony from 124 people. Two-thirds of the complainants were men, now aged in their 50s and 60s.[21] [22]

The first signs of the scandal date back to 1992 when Louis Dupont, the parish priest of Kinkempois (near Liège), was sentenced to five years in prison for the statutary rape of a 14-year-old girl. In a move from tradition, Dupont was allowed to serve his time under ecclesiastical supervision in a monastery, while his two male accomplices served much longer terms in state prison.[23][24] The trial took place in a courtroom closed to the public.[25]

A few years later in 1996, Louis André, parish priest of the hamlet of Ottré in the Province of Luxembourg (not to be confounded with the neighbouring Grand Duchy of Luxembourg), was arrested and accused of the rape of two boys. He was set free eight months later. He was then ordered by Church authorities to leave his post and retire to a monastery, but he successfully resisted the order, supported by a group of his parishioners.[26] Four years later, however, André was accused of several additional acts of sexual contact and rape, dating to between 1964 and 1996, including the alleged rape of several girls under 10 years old, one of whom was his own niece.[27] Although he denied any wrongdoing, he was convicted and served three years in prison before dying of cancer in 2003.[28][29]

In 1997, another Belgian priest was arrested for raping a minor, and he subsequently confessed to having intercourse with seven other people between 1968 and 1997. This was Abbot André Vanderlyn (aka Vander Lyn or Vander Lijn), the priest of a working-class parish in Brussels.[30]

In January 1998, Father Luc De Bruyne of the Congregation of the Fratres Van Dale in Torhout (near Bruges) was arrested for sexual abuse of four mentally disabled boys. De Bruyne had worked as a guidance counsellor in a "medico-pedagogic institute". He came to the attention of the institute in 1995, and was fired from his post. His religious order then sent him to Rwanda on the orders of the bishop of Bruges.[31] In November 2005, De Bruyne and his colleague "brother Roger H." were sentenced to ten years in prison for abusing more than 20 mentally disabled people over 16 years. De Bruyne denied the allegations and appealed the verdict. At the time of the verdict he was no longer a member of the religious order, and he was married with two children.[32]

Bart Aben of the Diocese of Ghent was arrested on 27 November 2009 for sexual conduct with two mentally disabled minors, which he admitted. He has since been released.[33]

In 1998 it was reported that a catechism textbook for Belgian children called Roeach 3 showed comic-book-style pictures of toddlers asking sexual questions and engaging in sexual play. The Belgian Catholic hierarchy stated that the textbook was intended for adolescents, and that the pictures were meant to convey the idea that young children experience lust, a prevalent theory in contemporary psychology. Nevertheless, the textbook was withdrawn after public protests by Catholics, which elicited media coverage as well as support from Church officials around the world.[34][35][36]

The editors of Roeach were Prof. Jef Bulckens of the Catholic University of Leuven and Prof. Frans Lefevre of the Seminary of Bruges.[37] The name "Roeach" refers to the Hebrew word Ruach (Hebrew: רוח), meaning "spirit" or "breath".

See also

References

- ↑ Jan De Volder, "Can Leonard Bridge the Divide?" The Tablet, 30 January 2010, 6.

- 1 2 "Catholic Church in Kingdom of Belgium". GCatholic.org. 2 March 2015. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- ↑ "Kerkpraktijk In Vlaanderen Table 1 page 115 PDF document in Dutch" (PDF). Soc.kuleuven.be. Retrieved 2014-03-18.

- ↑ Auteur: Veerle Beel. "7 procent nog wekelijks naar de mis - Het Nieuwsblad". Nieuwsblad.be. Retrieved 2014-03-18.

- ↑ "Met uitsterven bedreigd: de Brusselse kerkganger | Brusselnieuws" (in Dutch). Brusselnieuws.be. 2010-11-30. Retrieved 2014-03-18.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-07-10. Retrieved 2016-07-10.

- ↑ Hooghe Marc, Quintelier Ellen & Reeskens Tim, "Kerkpraktijk in Vlaanderen. Trends en extrapolaties 1967-2004." Ethische Perspectieven, 16(2) (2006), pp. 113-123.

- 1 2 Robert Mickens, "Where have all the thinkers gone?" (interview), in The Tablet, May 31, 2008: 6-7.

- ↑ De Volder, 6.

- ↑ Télémoustique, n° 4281, 30 December 2009. Also Télémoustique, n° 4281, 30 June 2010

- ↑ Roland Planchar, "Eglise et pédophilie : les scandales belges", Le Vif, 22 March 2010.

- 1 2 Pope pained by Belgian child sex scandal, September 13, 2010, CNN

- ↑ Elisabetta Povoledo, "Bishop, 73, in Belgium Steps Down Over Abuse", The New York Times, 23 April 2010.

- 1 2 DOREEN CARVAJAL and STEPHEN CASTLE, "Abuse Took Years to Ignite Belgian Clergy Inquiry", The New York Times, 12 July 2010.

- ↑ OLIVIER ROGEAU and MARIE-CECILE ROYEN, "Eglise belge : les dessous du scandale", Le Vif, 3 May 2010.

- ↑ "L'ABBÉ BORREMANS CONDAMNÉ À 5 ANS POUR VIOL SUR UN GAMIN DE 6 ANS", SudPresse, 21 April 2010.

- ↑ Jean-Pierre Borloo, "L’abbé Robert Borremans condamné pour viol", Le Soir, 23 January 2008.

- ↑ Jean-Pierre Borloo, "L’abbé Robert Borremans nie les viols sur son filleul", Le Soir, 11 March 2010.

- ↑ "Vatican 'indignant' over Belgium police raids". BBC News Online. BBC. 25 June 2010. Retrieved 5 July 2010.

- ↑ Carvajal, Doreen (28 June 2010). "Church Raid in Belgium Raises Dark Questions". The New York Times.

- ↑ Caroline Caldier, "Belgique : un rapport analyse les conséquences de la pédophilie dans l’Eglise", France Info, 10 September 2010.

- ↑ Radio Canada, "Rapport accablant de l'Église belge", 10 September 2010, accessed 22 September 2010.

- ↑ Roland Planchar, "Eglise et pédophilie : les scandales belges", 22 March 2010.

- ↑ "LE CURE DE KINKEMPOIS ECHAPPE A LA PRISON", Le Soir, 26 September 1992.

- ↑ René Haquin, "LES ENFANTS QU'ON N'A PAS CRU", Le Soir, 23 October 2000

- ↑ Luc Rosenzweig, "L'Eglise de Belgique est secouée par une série d'affaires de prêtres pédophiles", Le Monde, 29 December 1997

- ↑ René Haquin, "Pédophilie: huit ans après le curé de Kinkempois, celui d'Ottré est aux assises Le curé nie toutes les accusation" Le Soir, 16 October 2000.

- ↑ René Haquin, "Pour un grand nombre de crimes sexuels commis pendant une période extrêmement longue L'ex-curé condamné au maximum: 30 ans de réclusion Il n'y a plus de curé d'Ottré", Le Soir, 26 October 2000.

- ↑ Sabine Dorval, "Brèves Faits divers NAMUR Décès du curé d'Ottré", Le Soir, 5 April 2003.

- ↑ J-P Borloo, "Curé pédophile: le cardinal est civilement responsable Le prêtre Vander Lyn, de Saint-Gilles, a été condamné ce matin à 6 ans de prison. Danneels et Lanneau sont mis en cause.", Le Soir, 9 April 1998.

- ↑ Luc Surmont, [ "LE DIRECTEUR: "IL NE FAUT PAS TOUJOURS CROIRE CE QUE CES HANDICAPES MENTAUX RACONTENT", L'EVECHE DE BRUGES A COUVERT LE FRERE..."], Le Soir, 19 January 1998.

- ↑ http://www.katholieknederland.nl/actualiteit/2005/detail_objectID573995_FJaar2005.html

- ↑ http://www.demorgen.be/dm/nl/989/Binnenland/article/detail/1034844/2009/11/27/Overpeltse-pedofiele-pastoor-nog-zeker-maand-in-cel.dhtml and http://www.gva.be/nieuws/binnenland/aid903277/pedofiele-pastoor-uit-overpelt-niet-langer-in-de-cel-2.aspx

- ↑ "UN MANUEL DE CATECHESE QUI INCITE A LA PEDOPHILIE?" (in French). Le Soir. 10 February 1998. Retrieved 5 July 2010.

- ↑ Jan Peeters (29 April 2010). "Hartkwaal" (in Dutch). Katholiek Nieuwsblad. Archived from the original on 1 May 2010. Retrieved 5 July 2010.

- ↑ "Belgian Bishops Ignored Parents on Grossly Sexually Explicit Catholic 'Catechism'". LifeSiteNews. 6 July 2010. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- ↑ Alexandra Colen, "The Fall of the Belgian Church", The Brussels Journal, 24 June 2010.

External links

- Searchportal "Catholicism in Belgium" at http://www.parochiesinbeweging.be/zoekportaal/katholieken.html