Rodelinda (opera)

Rodelinda, regina de' Longobardi (HWV 19) is an opera seria in three acts composed for the first Royal Academy of Music by George Frideric Handel. The libretto is by Nicola Francesco Haym, and was based on an earlier libretto by Antonio Salvi set by Giacomo Antonio Perti in 1710. Salvi's libretto originated with Pierre Corneille's play Pertharite, roi des Lombards (1653), based on the history of Perctarit, king of the Lombards in the 7th century.

Performance history

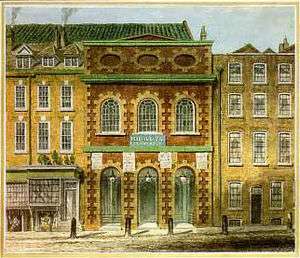

Rodelinda was first performed at the King’s Theatre in the Haymarket, London, on 13 February 1725. It was produced with the same singers as Tamerlano. There were 14 performances; it was repeated on 18 December 1725, and again on 4 May 1731, a further 16 performances in all, each revival including changes and fresh material.[1] In 1735 and 1736 it was also performed, with only modest success, in Hamburg at the Oper am Gänsemarkt. The first modern production - in heavily altered form - was in Göttingen on 26 June 1920 where it was the first of a series of modern Handel opera revivals produced by the Handel enthusiast Oskar Hagen.[1] The opera reached the US in 1931 and was revived in London in 1939.[2] A further notable London revival by the Handel Opera Society, in English and using a cut text, including both Joan Sutherland and Janet Baker in the cast, conducted by Charles Farncombe, was performed in June 1959.[2] With the revival of interest in Baroque music and historically informed musical performance since the 1960s, Rodelinda, like all Handel operas, receives performances at festivals and opera houses today.[3] Among other performances, Rodelinda was staged at the Glyndebourne Festival in the UK in 1998,[4] by the Metropolitan Opera in New York in 2004[5] and by English National Opera in 2014.[6] The ENO production was revived at the Bolshoi Theatre in 2015.[7]

Roles

| Role[1] | Voice type | Premiere Cast, 13 February 1725 |

|---|---|---|

| Rodelinda, Queen of Lombardy | soprano | Francesca Cuzzoni |

| Bertarido, usurped King of Lombardy | alto castrato | Francesco Bernardi, called "Senesino" |

| Grimoaldo, Duke of Benevento, Bertarido's usurper | tenor | Francesco Borosini |

| Eduige, Bertarido's sister, betrothed to Grimoaldo | contralto | Anna Vincenza Dotti |

| Unulfo, Bertarido's friend and counsellor | alto castrato | Andrea Pacini |

| Garibaldo, Grimoaldo's counsellor, duke of Turin | bass | Giuseppe Maria Boschi |

| Flavio, Rodelinda's son | silent |

Synopsis

Most scenes take place in the palace, but two scenes are set in the cemetery, with the final scene taking place outdoors. The action extends over one day, the final scene taking place shortly after sunrise. In the original source, Perctarit (Bertarido in the opera) flees, and his wife, Rodelinde (Rodelinda), along with their son Cunincpert (Flavio), are sent into exile; in the opera, Rodelinda remains in Milan (along with Flavio) and becomes the central figure. The actions around her must therefore all be regarded as fictitious.

Prologue

Grimoaldo has defeated Bertarido in battle and usurped his throne. Bertarido has fled, and it is believed that he has died in exile, but he sends word to his friend Unulfo that he is alive and in hiding near the palace. Grimoaldo is betrothed to Bertarido's sister Eduige, and though she loves him and he returns her affection, at least at first, she keeps putting off the wedding. Rodelinda and her son, Flavio, are being kept in the palace by Grimoaldo, who has fallen in love with her.

Act 1

Alone, Rodelinda mourns the loss of her husband. Grimoaldo enters and proposes marriage to her; he offers her the throne back, and confesses his love for her. She angrily rejects him.(Aria:"L'empio rigor del fato".) Eduige tells Grimoaldo that he has become treacherous now that he is king; he answers that he is treacherous for the sake of justice, referring to the fact that she so often refused to marry him and now he, at Garibaldo's instigation, is rejecting her. With Grimoaldo gone, the scheming Garibaldo, who has previously professed to love Eduige, offers to bring her Grimoaldo's head. She declines, but swears that she will be revenged eventually.(Aria:"Lo farò, diro: spietato"). Alone, Garibaldo details his plan to use Eduige to help him take the throne for himself.(Aria: "Di cupido impiego i vanni.")

Meanwhile, Bertarido reads the inscription on his own memorial.(Aria:"Dove sei, amato bene?") Along with Unulfo, he watches from hiding as Rodelinda and Flavio lay flowers at the memorial. Garibaldo enters and offers Rodelinda an ultimatum; either she agrees to marry Grimoaldo or Flavio will be killed. Rodelinda agrees, but warns Garibaldo that she will use his head as a step to the throne. Bertarido, still watching, takes Rodelinda's decision as an act of infidelity. Grimoaldo tells Garibaldo not to worry about Rodelinda's threat; under the king's protection, what does he have to fear? Unulfo, meanwhile, tries to comfort Bertarido, but Bertarido is unconvinced.

Act 2

Garibaldo, as part of his plan to take the throne, tells Eduige that it appears she has lost her chance to become queen, and encourages her to take revenge on Grimoaldo. Eduige then turns her bitterness on Rodelinda, pointing out Rodelinda's sudden decision to betray her husband's memory and marry his usurper. Rodelinda reminds Eduige of who is queen. Eduige again vows vengeance on Grimoaldo, though it is clear she still loves him. Eduige departs and Grimoaldo enters, asking Rodelinda if it is true that she's agreed to marry him. She assures him that it is true, but that she has one condition: Grimoaldo must first kill Flavio in front of her. Grimoaldo, horrified, refuses. Once Rodelinda departs, Garibaldo encourages Grimoaldo to carry out the murder and take Rodelinda as his wife, but Grimoaldo again refuses. He says that Rodelinda's act of courage and determination has made him love her all the more, though he has lost all hope of ever winning her over. Unulfo asks Garibaldo how he could give a king such appalling advice, and Garibaldo expounds his Macchiavellian perspective on the use of power. Bertarido, meanwhile, has approached the palace grounds in disguise, where Eduige recognizes him. She agrees to tell Rodelinda that her husband is still alive. Rodelinda and Bertarido meet in secret, but are discovered by an outraged Grimoaldo. He doesn't recognize Bertarido, but vows to kill him anyway, whether he be Rodelinda's real husband or just her lover. The spouses, before being separated again, bid each other a last farewell. (Duet: ""Io t'abbraccio".)

Act 3

Unulfo and Eduige make a plan to release Bertarido from prison; they'll smuggle him a weapon and the key to the secret passage that runs under the palace. Grimoaldo, meanwhile, is having a crisis of conscience over the impending execution. Bertarido, in his cell, receives his package. Unulfo, who is allowed access to the prison in an official capacity, comes to release Bertarido. Bertarido, however, can't recognize Unulfo in the darkness, and mistakenly wounds him with the sword. Unulfo shrugs the injury off, and the two leave. Eduige and Rodelinda, meanwhile, have come to visit Bertarido. Finding the cell empty and blood on the floor, they despair of his life. Grimoaldo is still struggling with conscience and flees to the palace garden, hoping to find a peaceful spot where he can finally fall asleep; even shepherds, he laments, can find rest under trees and bushes, but he, a king, can find no rest anywhere.(Aria:"Pastorello d'un povero armento".) He finally falls asleep, but Garibaldo finds him and decides to take advantage of the situation. He is about to kill Grimoaldo with his own sword when Bertarido enters and kills Garibaldo. Grimoaldo, however, he spares.(Aria:""Vivi, tiranno!") Grimoaldo gladly gives up all claim to the throne and turns to Eduige, telling her that they shall wed and rule together in his own duchy. Reunited at last, the family rejoices.[8]

Context and analysis

The German-born Handel, after spending some of his early career composing operas and other pieces in Italy, settled in London, where in 1711 he had brought Italian opera for the first time with his opera Rinaldo. A tremendous success, Rinaldo created a craze in London for Italian opera seria, a form focused overwhelmingly on solo arias for the star virtuoso singers. In 1719, Handel was appointed music director of an organisation called the Royal Academy of Music (unconnected with the present day London conservatoire), a company under royal charter to produce Italian operas in London. Handel was not only to compose operas for the company but hire the star singers, supervise the orchestra and musicians, and adapt operas from Italy for London performance.[9][10]

Within a year, 1724-1725, Handel wrote three great operas in succession for the Royal Academy of Music, each with Senesino and Francesca Cuzzoni as the stars, the other two being Giulio Cesare and Tamerlano.[11]

Horace Walpole wrote of Cuzzoni in Rodelinda:

She was short and squat, with a doughy cross face, but fine complexion; was not a good actress; dressed ill; and was silly and fantastical. And yet on her appearing in this opera, in a brown silk gown trimmed with silver, with the vulgarity and indecorum of which all the old ladies were much scandalised, the young adopted it as a fashion, so universally, that it seemed a national uniform for youth and beauty.[11]

To 18th century musicologist Charles Burney Rodelinda "contains such a number of capital and pleasing airs, as entitles it to one of the first places among Handel’s dramatic productions". Burney notes particularly the aria for Bertarido in Act Two, "Dove sei, amato bene", calling it

one of the finest pathetic airs that can be found in all his works... This air is rendered affecting by new and curious modulation, as well as by the general cast of the melody.[12]

The opera is scored for two recorders, flute, two oboes, bassoon, two horns, strings and continuo (cello, lute, harpsichord).

Recordings

Audio recordings

| Year | Cast: Rodelinda,Bertarido, Grimoaldo, Eduige, Unolfo, Garibaldo |

Conductor, orchestra |

Label[13][14] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1959 | Joan Sutherland, Margreta Elkins, Alfred Hallett, Janet Baker, Patricia Kern, Raymond Herincx |

Charles Farncombe, Philomusica Orchestra |

CD:Andromeda Cat:ANDRCD9075 |

| 1964 | Teresa Stich-Randall, Maureen Forrester, Alexander Young, Hilde Rössel-Majdan, Helen Watts, John Boyden |

Brian Priestman, Vienna Radio Orchestra |

CD:The Westminster Legacy Cat:DG 4792343 |

| 1985 | Joan Sutherland, Alicia Nafé, Curtis Rayam, Isobel Buchanan, Huguette Tourangeau, Samuel Ramey |

Richard Bonynge Welsh National Opera Orchestra |

CD:Australian Eloquence Cat: ELQ4806105 |

| 1996 | Sophie Daneman, Daniel Taylor, Adrian Thompson, Catherine Robbin, Robin Blaze, Christopher Purves |

Nicholas Kraemer Raglan Baroque Players |

CD:Virgin Classics Veritas Cat: 45277 |

| 2004 | Simone Kermes, Marijana Mijanovic, Steve Davislim, Sonia Prina, Marie-Nicole Lemieux, Vito Priante |

Alan Curtis Il Complesso Barocco |

CD:DG Archiv Cat:4775391 |

Video recordings

| Year | Cast: Rodelinda,Bertarido, Grimoaldo, Eduige, Unolfo, Garibaldo |

Conductor, orchestra |

Stage director | Label |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1998 | Anna Caterina Antonacci, Andreas Scholl, Kurt Streit, Louise Winter, Artur Stefanowicz. Umberto Chiummo |

William Christie Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment |

Jean-Marie Villegier | DVD:Warner Classics Cat:3984230242 |

| 2003 | Dorothea Röschmann, Michael Chance, Paul Nilon, Felicity Palmer, Christopher Robson, Umberto Chiummo |

Ivor Bolton Bavarian State Opera Orchestra |

David Alden | DVD:Farao Cat:D108060 |

| 2012 | Renee Fleming, Andreas Scholl, Joseph Kaiser, Stephanie Blythe, Iestyn Davies, Shenyang |

Harry Bicket Metropolitan Opera Orchestra, (Recording of a performance at the MET on 3 December 2011) |

Stephen Wadsworth | DVD:Decca Cat:0743469 |

References

Notes

- 1 2 3 "Rodelinda, regina de' Langobardi". Gfhandel.org. Handel Institute. Retrieved 24 June 2014.

- 1 2 Sadie, Stanley (2009). Grove Book of Operas. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195387117.

- ↑ "Handel:A Biographical Introduction". Handel Institute. Retrieved 30 May 2014.

- ↑ Ashley, Tim (15 June 2004). "Rodelinda". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ↑ "GP at The Met: Rodelinda". PBS.org. PBS. Retrieved 24 June 2014.

- ↑ Maddocks, Fiona. "Rodelinda review – as restrained as it is over the top". The Observer. Retrieved 24 June 2014.

- ↑ Bolshoi Theatre (13 December 2015). Press release: "A Lively Story". Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- ↑ "Synopsis of Rodelinda". Metopera.org. Retrieved 24 June 2014.

- ↑ Dean, W. & J.M. Knapp (1995) Handel's operas 1704-1726, p. 298.

- ↑ Essays on Handel and Italian opera by Reinhard Strohm. Retrieved 2013-02-02 – via Google Books.

- 1 2 "Rodelinda". Handelhouse.org. Handel House Museum. Retrieved 24 June 2014.

- ↑ Charles Burney: A General History of Music: from the Earliest Ages to the Present Period. Vol. 4. London 1789, reprint: Cambridge University Press 2010, ISBN 978-1-1080-1642-1, p. 301.

- ↑ "Recordings of Rodelinda". Operadis.org.uk. Retrieved 24 June 2014.

- ↑ "Recordings of Rodelinda". Prestoclassical.co.uk. Retrieved 24 June 2014.

Sources

- Dean, Winton; Knapp, J. Merrill (1987), Handel's Operas, 1704-1726, Clarendon Press, ISBN 0193152193 (Volume 1 of the two-volume definitive text on the operas of Handel.)

- Hicks, Anthony, "Rodelinda", The New Grove Dictionary of Opera, ed. Stanley Sadie (London, 1992) ISBN 0-333-73432-7

External links

- Italian libretto.

- Score of Rodelinda (Ed. Friedrich Chrysander, Leipzig 1876) Retrieved 6 September 2011