Roads and freeways in metropolitan Detroit

| Roads and Freeways in Metropolitan Detroit | |

|---|---|

|

Highway markers for I‑75 and M‑10 | |

|

Map of Detroit Metro Area freeways | |

| System information | |

| Formed: | 1805[1] |

| Highway names | |

| Interstates: | Interstate nn (I‑nn) |

| US Highways: | US Highway nn (US nn) |

| State: | M‑nn |

| System links | |

The roads and freeways in metropolitan Detroit comprise the main thoroughfares in the region. The freeways consist of an advanced network of interconnecting freeways which include Interstate highways. The Metro Detroit region's extensive toll-free freeway system, together with its status as a major port city, provide advantages to its location as a global business center.[2] There are no toll roads in Michigan.[3]

Detroiters may refer to freeways by the formal name more often where one has been designated rather than route number. Other freeways without formal names are known by the number such as I‑275 and M‑59. M‑53, while not officially designated may be locally referred to by its name "Van Dyke". Detroit area freeways are typically sunken below ground level to permit local traffic to pass over the freeway and for appearance.[4]

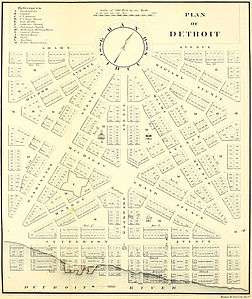

Following a historic fire in 1805, Judge Augustus B. Woodward devised a plan similar to Pierre Charles L'Enfant's design for Washington, D.C.. Detroit's monumental avenues and traffic circles fan out in a baroque styled radial fashion from Grand Circus Park in the heart of the city's theater district, which facilitates traffic patterns along the city's tree-lined boulevards and parks.[5] The 'Woodward plan' proposed a system of hexagonal street blocks, with the Grand Circus at its center. Wide avenues, alternatively 200 feet (61 m) and 120 feet (37 m), would emanate from large circular plazas like spokes from the hub of a wheel. As the city grew these would spread in all directions from the banks of the Detroit River. When Woodward presented his proposal, Detroit had fewer than 1,000 residents. Elements of the plan were implemented. Most prominent of these are the five main "spokes" of Woodward, Michigan, Gratiot, Grand River and Jefferson Avenues.

The Mile Road System in Metro Detroit and Southeast Michigan facilitates ease of navigation in the region. It was established as a way to delineate east–west roads through the Detroit area and the surrounding rural rim. The Mile Road system, and its most famous road, 8 Mile Road, came about largely as a result of the Land Ordinance of 1785, which established the basis for the Public Land Survey System in which land throughout the Northwest Territory was surveyed and divided into survey townships by reference to a baseline (east–west line) and meridian (north–south line). In Southeast Michigan, many roads would be developed parallel to the base line and the meridian, and many of the east–west roads would be incorporated into the Mile Road System.

The Mile Road System extended easterly into Detroit, but is interrupted, because much of Detroit's early settlements and farms were based on early French land grants that were aligned northwest-to-southeast with frontage along the Detroit River and on later development along roads running into downtown Detroit in a star pattern, such as Woodward, Jefferson, Grand River, Gratiot, and Michigan Avenues, developed by Augustus Woodward in imitation of Washington, D.C.'s system. As Detroit grew, several Mile Roads were given new names within the city borders, while some roads incorporated as part of the Mile Road System have traditionally been known by their non-mile names. It is unclear if they ever bore mile numbers formally.

The baseline used in the survey of Michigan lands runs along 8 Mile Road, which is approximately eight miles directly north of the junction of Woodward Avenue and Michigan Avenue in downtown Detroit. As a result, the direct east–west portion of Michigan Avenue, and M‑153 (Ford Road) west of Wyoming Avenue, forms the "zero mile" baseline for this mile road system.

The precise point of origin is located in Campus Martius Park, marked by a medallion[6] embedded in the stone walkway. It is situated in the western point of the diamond surrounding Woodward Fountain,[7] just in front of the Fountain Bistro.

Freeways

.png)

I-75 (known as the Walter P. Chrysler Freeway from Downtown Detroit to Pontiac in the north and Fisher Freeway though southern and central Detroit) is the region's main north-south route, serving Flint, Pontiac, Troy, and Detroit, before continuing south (as the Detroit-Toledo and Seaway Freeways) to serve the Downriver communities and further south, many of the communities along the shore of Lake Erie, most notably Toledo, Ohio before continuing to Florida.

I-75 (known as the Walter P. Chrysler Freeway from Downtown Detroit to Pontiac in the north and Fisher Freeway though southern and central Detroit) is the region's main north-south route, serving Flint, Pontiac, Troy, and Detroit, before continuing south (as the Detroit-Toledo and Seaway Freeways) to serve the Downriver communities and further south, many of the communities along the shore of Lake Erie, most notably Toledo, Ohio before continuing to Florida. I-94 (Edsel Ford Freeway & Detroit Industrial Freeway) runs east-west through Detroit and serves Ann Arbor to the west (where it continues to West Michigan and Chicago) and Port Huron to the northeast. The stretch of the current I‑94 freeway from Ypsilanti to Detroit was one of America's earlier limited-access highways. Henry Ford built it to link his factories at Willow Run and Dearborn during World War II. It also serves the North Access to the Detroit Metro Airport in Romulus. A portion was known as the Willow Run Expressway.

I-94 (Edsel Ford Freeway & Detroit Industrial Freeway) runs east-west through Detroit and serves Ann Arbor to the west (where it continues to West Michigan and Chicago) and Port Huron to the northeast. The stretch of the current I‑94 freeway from Ypsilanti to Detroit was one of America's earlier limited-access highways. Henry Ford built it to link his factories at Willow Run and Dearborn during World War II. It also serves the North Access to the Detroit Metro Airport in Romulus. A portion was known as the Willow Run Expressway. I‑96 runs east-west through Livingston, Oakland and Wayne counties and has its eastern terminus in downtown Detroit. The portion east of I‑275 is known and signed as the Jeffries Freeway, named for Edward Jeffries (a former mayor of Detroit); however, this portion of I‑96 was officially renamed by the state legislature as the Rosa Parks Memorial Highway in December 2005.[8]

I‑96 runs east-west through Livingston, Oakland and Wayne counties and has its eastern terminus in downtown Detroit. The portion east of I‑275 is known and signed as the Jeffries Freeway, named for Edward Jeffries (a former mayor of Detroit); however, this portion of I‑96 was officially renamed by the state legislature as the Rosa Parks Memorial Highway in December 2005.[8] I-275 runs north-south from I‑75 in the south to the junction of I‑96 and I‑696 in the north, providing a bypass through the western suburbs of Detroit. Originally intended to travel north 23 miles (originally as I‑275 and later changed to M‑275) from the I‑696/I‑96/I‑275/M‑5 junction to the I‑75/US 24 (Dixie Hwy.) junction) in Waterford Twp., where I‑75's median was significantly widened in its initial construction to accommodate the future interchange. The planned M‑275 has essentially been scrapped, with the northward extension of M‑5 utilizing the original M‑275 right-of-way but terminating after just 6 miles at Pontiac Trail in West Bloomfield.

I-275 runs north-south from I‑75 in the south to the junction of I‑96 and I‑696 in the north, providing a bypass through the western suburbs of Detroit. Originally intended to travel north 23 miles (originally as I‑275 and later changed to M‑275) from the I‑696/I‑96/I‑275/M‑5 junction to the I‑75/US 24 (Dixie Hwy.) junction) in Waterford Twp., where I‑75's median was significantly widened in its initial construction to accommodate the future interchange. The planned M‑275 has essentially been scrapped, with the northward extension of M‑5 utilizing the original M‑275 right-of-way but terminating after just 6 miles at Pontiac Trail in West Bloomfield. I-375 is a short spur route in downtown Detroit, an extension of the Chrysler Freeway.

I-375 is a short spur route in downtown Detroit, an extension of the Chrysler Freeway. I‑696 (Walter P. Reuther Freeway) runs east-west from the junction of I‑96 and I‑275 on the west to I‑94 on the east, providing a route through the northern suburbs of Detroit. Taken together, I‑275 and I‑696 form a beltway around Detroit. Originally designated for the Lodge Fwy. (which is currently now designated as M‑10).

I‑696 (Walter P. Reuther Freeway) runs east-west from the junction of I‑96 and I‑275 on the west to I‑94 on the east, providing a route through the northern suburbs of Detroit. Taken together, I‑275 and I‑696 form a beltway around Detroit. Originally designated for the Lodge Fwy. (which is currently now designated as M‑10). M-5 This freeway begins as the stub leftover from the Brighton-Farmington Expressway after Interstate 96 was rerouted to the Jeffries. Originally designated as I‑96 and later as an extension of M‑102. From 1994 to 2002, it was extended north as the Haggerty Connector.[9]

M-5 This freeway begins as the stub leftover from the Brighton-Farmington Expressway after Interstate 96 was rerouted to the Jeffries. Originally designated as I‑96 and later as an extension of M‑102. From 1994 to 2002, it was extended north as the Haggerty Connector.[9] M-8 is the Davison Freeway. Opened in 1942, this was the first modern depressed limited-access freeway in America. Originally supposed to run as a freeway from I‑96 east to Mound Rd. and the north to join the already-existing M‑53 Fwy. at Van Dyke Ave.in Sterling Heights. In 1996 the Davison was closed for a year and a half to reconstruct it to Interstate Highway standards with an additional through travel lane and a wider left shoulder for improved safety and traffic handling as well as a new interchange with Woodward Avenue. The reconstructed freeway was reopened 18 months later on October 8, 1997

M-8 is the Davison Freeway. Opened in 1942, this was the first modern depressed limited-access freeway in America. Originally supposed to run as a freeway from I‑96 east to Mound Rd. and the north to join the already-existing M‑53 Fwy. at Van Dyke Ave.in Sterling Heights. In 1996 the Davison was closed for a year and a half to reconstruct it to Interstate Highway standards with an additional through travel lane and a wider left shoulder for improved safety and traffic handling as well as a new interchange with Woodward Avenue. The reconstructed freeway was reopened 18 months later on October 8, 1997 M-10 (John C. Lodge Freeway) runs largely parallel to I‑75 from Downtown Detroit to Wyoming Ave., where is turns northwesterly and largely maintains this trajectory through the I‑696/Telegraph Rd. interchange in Southfield and then continues as a surface boulevard as Northwestern Hwy., terminating at Orchard Lake Rd. in Farmington Hills.

M-10 (John C. Lodge Freeway) runs largely parallel to I‑75 from Downtown Detroit to Wyoming Ave., where is turns northwesterly and largely maintains this trajectory through the I‑696/Telegraph Rd. interchange in Southfield and then continues as a surface boulevard as Northwestern Hwy., terminating at Orchard Lake Rd. in Farmington Hills. M-14 runs east-west from I‑275 in Livonia to Ann Arbor.

M-14 runs east-west from I‑275 in Livonia to Ann Arbor. M-39 (Southfield Freeway) runs north-south from Southfield to Allen Park. North of 9 Mile Road and south of I‑94, the freeway ends and continues as Southfield Road into Birmingham and Ecorse respectively.

M-39 (Southfield Freeway) runs north-south from Southfield to Allen Park. North of 9 Mile Road and south of I‑94, the freeway ends and continues as Southfield Road into Birmingham and Ecorse respectively. M-53 (Christopher Columbus Freeway from Sterling Heights to Washington), more commonly known as the Van Dyke Expressway or Van Dyke Freeway. Continues as Van Dyke Road or Van Dyke Avenue north to Port Austin and south through Warren to Gratiot Avenue in Detroit.

M-53 (Christopher Columbus Freeway from Sterling Heights to Washington), more commonly known as the Van Dyke Expressway or Van Dyke Freeway. Continues as Van Dyke Road or Van Dyke Avenue north to Port Austin and south through Warren to Gratiot Avenue in Detroit. M-59 (Veterans Memorial Freeway from Utica to Pontiac), continues east as Hall Road to Clinton Township and west as Huron Road through Pontiac and Waterford, and as Highland Road further west through Highland and Milford to I‑96 near Howell. Originally intended to be a limited-access freeway between US 23 on the west and I‑94 on the east.

M-59 (Veterans Memorial Freeway from Utica to Pontiac), continues east as Hall Road to Clinton Township and west as Huron Road through Pontiac and Waterford, and as Highland Road further west through Highland and Milford to I‑96 near Howell. Originally intended to be a limited-access freeway between US 23 on the west and I‑94 on the east.

Other selected major roads

M-102 (8 Mile Road), known by many through the film 8 Mile, forms the dividing line between Detroit on the south and the suburbs of Macomb and Oakland counties on the north. Outside of Detroit it is also known as Base Line Road, because it coincides with the baseline used in surveying Michigan; that baseline is also a boundary for several other Michigan counties. 8 Mile is designated as M‑102 for much of its length in Wayne County. For several years the M‑102 designation continued from its current terminus at Grand River Ave. and followed the old I‑96 freeway to the I‑96/I‑696/I‑275 interchange; this stretch, along with the rest of Grand River southeast to Downtown Detroit, is now signed as M‑5. The portion of M‑102 from Grand River Avenue east to M‑3 (Gratiot Avenue) is designated as the "Columbus Memorial Highway."

M-102 (8 Mile Road), known by many through the film 8 Mile, forms the dividing line between Detroit on the south and the suburbs of Macomb and Oakland counties on the north. Outside of Detroit it is also known as Base Line Road, because it coincides with the baseline used in surveying Michigan; that baseline is also a boundary for several other Michigan counties. 8 Mile is designated as M‑102 for much of its length in Wayne County. For several years the M‑102 designation continued from its current terminus at Grand River Ave. and followed the old I‑96 freeway to the I‑96/I‑696/I‑275 interchange; this stretch, along with the rest of Grand River southeast to Downtown Detroit, is now signed as M‑5. The portion of M‑102 from Grand River Avenue east to M‑3 (Gratiot Avenue) is designated as the "Columbus Memorial Highway." M-3 (Gratiot Avenue) is a major road that runs from New Baltimore to downtown Detroit.

M-3 (Gratiot Avenue) is a major road that runs from New Baltimore to downtown Detroit.- Jefferson Avenue is a scenic highway whose northern leg runs between M‑10 in Downtown Detroit along the Detroit River and Lakes St. Clair to New Baltimore. The portion is also the principal thoroughfare for the Grosse Pointes, where it is called Lake Shore Drive. Another important dividing line between Detroit and the city of Grosse Pointe Park is Alter Road, where portions of some intersecting streets have been reconfigured or walled-off in order to thwart vehicular and pedestrian movement from Detroit into Grosse Pointe Park. As a major thoroughfare, Jefferson's southern leg (sometimes designated as Biddle Rd. in some Downriver communities) runs from Dearborn St. in Detroit south (again, running mostly adjacent to the Detroit River) to a point just north of Huron River Dr. in Newport, where its name changes to U.S. Turnpike Rd. and then Dixie Hwy., (both segments of which parallel the Lake Erie shoreline) to terminate in Monroe. In Detroit north of Dearborn St., Jefferson is reduced to two-lane road that is disjointed at Clark St. It resumes one block north at Scotten St. as a side street north to 21st St. (at the Ambassador Bridge over-crossing), at which point a gate frequently prevents traffic from proceeding. From 21st St. to Rosa Parks Blvd., Jefferson is largely unpaved. And between Rosa Parks and M‑10, Jefferson is a four lane road, although this segment is not nearly utilized as much as the portion north of M‑10. The portion of Jefferson between the Rough River over-crossing and Rosa Parks Blvd. is heavily industrial and bucks the avenue's otherwise consistent trend as a pleasant scenic byway.

US 12 (Michigan Avenue) runs from downtown Detroit through the western suburbs toward Ypsilanti, passes south of Ann Arbor, and eventually reaches Chicago.

US 12 (Michigan Avenue) runs from downtown Detroit through the western suburbs toward Ypsilanti, passes south of Ann Arbor, and eventually reaches Chicago. M-1 (Woodward Avenue) is considered the Detroit area's main north-south thoroughfare. It is the dividing line between the East Side and the West Side. Woodward stretches from downtown Pontiac to the Detroit River near Hart Plaza. In Downtown Detroit, the Fox Theatre and Detroit Institute of Arts are located on Woodward as well as the Detroit Zoo just outside the city. The Woodward Dream Cruise, a classic car cruise from Pontiac to Ferndale is held in August and is the largest single day classic car cruise in America.

M-1 (Woodward Avenue) is considered the Detroit area's main north-south thoroughfare. It is the dividing line between the East Side and the West Side. Woodward stretches from downtown Pontiac to the Detroit River near Hart Plaza. In Downtown Detroit, the Fox Theatre and Detroit Institute of Arts are located on Woodward as well as the Detroit Zoo just outside the city. The Woodward Dream Cruise, a classic car cruise from Pontiac to Ferndale is held in August and is the largest single day classic car cruise in America. US 24 (Telegraph Road) is a major north-south road extending from Toledo, Ohio through Monroe, Wayne, and Oakland Counties to Pontiac. It has gained notoriety in a song (Telegraph Road) by the group Dire Straits.

US 24 (Telegraph Road) is a major north-south road extending from Toledo, Ohio through Monroe, Wayne, and Oakland Counties to Pontiac. It has gained notoriety in a song (Telegraph Road) by the group Dire Straits.- Dixie Highway is one of America's historic highways. Its eastern division extended from Miami, Florida, to Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan. The remnants of this highway exist northbound and southbound through the Detroit metropolitan area.

M-85 (Fort Street) is a major road through southwest Detroit before becoming a major boulevard through Downriver. It extends from Flat Rock to downtown Detroit.

M-85 (Fort Street) is a major road through southwest Detroit before becoming a major boulevard through Downriver. It extends from Flat Rock to downtown Detroit.- Grand River Avenue runs from Grand Rapids east through Lansing and then connects the suburbs of Brighton, Novi, and Farmington to downtown Detroit. It is one of the five roads planned by Judge Augustus Woodward to radiate out from Detroit and connect the city to other parts of the state. It extends out to Lansing and Grand Rapids(the segment of the road that runs between these two cities follows the trajectory of the Grand River) and is the main road and the dividing line between the city of East Lansing and the campus of Michigan State University. It formerly carried the designation US 16 prior to that route number's decommissioning in Michigan, and now parts of it are designated as M‑5 through Oakland and Wayne Counties and as M‑43 between Lansing and Webberville). There is also a small portion of Grand River Ave. designated as M‑52 as well as several areas where its designation is Business (Loop or Spur) I‑96.

Mile roads traveling north

Mile roads within Wayne County

The mile roads that cross through Wayne County are designated as follows:

- 0 Mile—Michigan Avenue in Detroit; Ford Road west of Detroit, though Ford Road does straddle the Detroit city limits for some blocks. Michigan Avenue is slightly north of Ford Road. Occupied by Cadillac Square east of Campus Martius.

- 1 Mile—Warren Avenue (turns east-northeastward at 25th Street in Detroit to conform with the Woodward plan). Western county line to Mack Avenue on the Detroit/Grosse Pointe Farms limits. Deviates off-grid to the south between just east of Lilley Road in Canton to Central City Parkway Road in Westland. From the west, for a half-mile east of the western county line, it is not paved.

- 2 Mile—Joy Road (also turns east-northeastward (at Livernois), but for a shorter distance). Western county line to Linwood Street in Detroit. Interrupted twice, first between Hines Drive and Wayne Road on the Westland/Livonia border and again just before the western county line, where its gridline is occupied by Ann Arbor Road.

- 3 Mile—Plymouth Road. Mill Street in Plymouth (here it continues westward as Main Street) to the intersection of Grand River Avenue and Cloverlawn Street (one block west of Oakman Boulevard) in Detroit. Runs off-grid west of the Ann Arbor Road split in Livonia.

- 4 Mile—Schoolcraft Avenue/Street (Detroit's west side); Schoolcraft Road (mostly now the service drive for I‑96). 5 Mile Road in Plymouth to Ewald Circle in Detroit. Occupied by Miller Street on Detroit's east side.

Note that the 0-4 Mile roads are not signed and never referred to as Mile Roads; it remains unclear if they were ever signed as Mile Roads. There is a Three Mile Drive in the far eastern portion of Detroit and going into Grosse Pointe Park, but it is unclear if this was ever intended to be a part of the Mile Road System.

- 5 Mile—Fenkell Street (Detroit's west side); 5 Mile Road (west of Detroit). Western county line to Rosa Parks Boulevard in Detroit. Occupied by Lynch Road on Detroit's east side.

- 6 Mile—McNichols Road (Detroit); 6 Mile Road (west of Detroit). Western county line to Gratiot Avenue in Detroit.

- 7 Mile—7 Mile Road (Detroit and west of Detroit). Western county line to Kelly Road in Detroit.

- 7 1⁄2 Mile Road (Pembroke Ave.); I‑275 to Woodward Ave. (not fully continuous since its cut into section. from I‑275 in Livonia to Woodward Ave. in Detroit)

- 8 Mile—8 Mile Road (Detroit and suburbs); Base Line Road (west of Detroit); also signed as M‑102 from Grand River Avenue to Vernier Road.

Note: On Detroit's far east side, which is aligned according to the French colonial long lot system rather than the Northwest Ordinance survey grid, Cadieux, Moross, and Vernier Roads are not extensions of 6 Mile Road, 7 Mile Road and 8 Mile Road, respectively. East McNichols (6 Mile) ends at Gratiot Avenue, with traffic continuing to Cadieux two miles (3 km) away via Seymour Street and Morang Drive. East 7 Mile Road ends as a short four-lane one-way side street at Kelly Road, two blocks east of where Moross veers off from 7 Mile, taking most traffic with it. Most traffic on 8 Mile Road continuing east of Kelly Road veers onto Vernier Road; 8 Mile continues as a side street eastward for a short distance past Harper Avenue. This is a common misconception by residents of Detroit, Harper Woods and Grosse Pointe, as Cadieux, Moross and Vernier appear to be extensions of their mile-road neighbors, but are in fact roads in their own right.

In the city of Detroit, residents only refer to 3 of the mile roads; 6, 7, & 8 Mile. 6 Mile Road is signed as "McNichols" throughout the city of Detroit, but is often referred to as "6 Mile" by residents. 5 Mile road, on the other hand, is almost always referred to as "Fenkell" (which is how it is signed in Detroit), and only very rarely as "5 Mile". The dual naming of McNichols is an occasional source of confusion to out-of-town travelers.

Although not signed as such, Detroit also has roads along half-mile grid lines:

- 1⁄2 Mile—Paul Street (Dearborn and Detroit), Ann Arbor Trail (for a short distance), Hass Avenue (Dearborn Heights), Maplewood Avenue (Garden City), Hunter Street (Westland), Hanford Road (Canton)

- 1 1⁄2 Mile—Tireman Avenue/Street (Detroit (there turns east-northeastward), Dearborn and Dearborn Heights), Ann Arbor Trail (also for a short distance), Koppernick Street/Road (for a short distance in Westland), Gyde Road (Canton)

- 2 1⁄2 Mile—Chicago Boulevard/Avenue/Street (once again, turns east-northeastward)

- 3 1⁄2 Mile—Fullerton Avenue/Street (once again, turns east-northeastward)

- 4 1⁄2 Mile—Lyndon Avenue/Street

- 5 1⁄2 Mile—Puritan Avenue/Street (once again, turns east-northeastward)

- 6 1⁄2 Mile—Curtis Avenue/Street (west of Woodward), Nevada Street, Greiner Street (east of Woodward)

- 7 1⁄2 Mile—Pembroke Avenue (west of Woodward), Outer Drive, State Fair Street (east of Woodward)

Mile roads within Washtenaw County

Few of the mile roads continue west into Washtenaw County.

- 0 Mile (M‑153)—Ford Road—Runs off the grid to meet M‑14. This is the only portion of Ford Road within Washtenaw County that is paved.

- 0 Mile (West of M‑153)—Ford Road—West to Earhart Road, interrupted between Plymouth and Dixboro roads.

- 1 Mile—Warren Road—Eastern county line west to Whitmore Lake Road, interrupted between Berry and Curtis Roads due to M‑14. Paved for a short distance west of Curtis Road.

- 2 Mile—Joy Road—Eastern county line west to Mast Road near Dexter. Runs off the grid west of Whitmore Lake Road.

- 5 Mile—Eastern county line west to a dead end west of Whitmore Lake Road, interrupted between Spencer and Nollar Roads.

- 6 Mile—Eastern county line west to Whitmore Lake Road, interrupted between Spencer and Nollar Roads, where it falls off the grid westward.

- 7 Mile—Eastern county line west to East Shore Drive near Whitmore Lake. Has a T-intersection with Tower Road and then resumes off the grid.

- 8 Mile—Eastern county line west to Hall Road. Interrupted between Spencer Road and US 23 due to Whitmore Lake.

Mile roads within Livingston County

Few of the mile roads continue west into Livingston County.

- 8 Mile Road

- 9 Mile—Eastern county line west to Spicer Road. Signed as M‑36 from US 23 to Spicer Road. Runs off-grid west of US 23.

- 10 Mile—Eastern county line west to Rushton Road.

- 12 Mile—Eastern county line west to Rushton Road.

Mile roads within Oakland County

The mile roads in the southernmost part of Oakland County are known only by their numbers. From 15 Mile Road northward, however, all mile roads have local names, sometimes several. And like Macomb County and Detroit, some roads are placed at half-mile intervals.

- 8 Mile Road

- 8 1⁄2 Mile Road—Madge Avenue (Hazel Park), Wordsworth and Alberta Streets (Ferndale), Northend Avenue (Oak Park and Royal Oak Township), Midway Avenue/Road and Frederick Street (Southfield), Independence and Colfax Streets (Farmington Hills)

- 9 Mile Road

- 9 1⁄2 Mile Road—Fink Avenue and Eldon Street (Farmington Hills), Mount Vernon Street (Southfield), Oak Park Boulevard (Oak Park), Woodward Heights Boulevard (Ferndale, Hazel Park)

- 10 Mile Road—Lake Street (through South Lyon), service drive for I‑696 from approximately Coolidge Highway to I‑75, where I‑696 swerves north a half-block before turning northeastward near Dequindre Road.

- 10 1⁄2 Mile Road—Lincoln Avenue, Civic Center Drive (Southfield)

- 11 Mile Road—service drive for I‑696 from approximately Greenfield Road to approximately Lahser Road, where I‑696 swerves slightly south.

- 11 1⁄2 Mile Road—Gardenia Avenue, Catalpa Drive, Saratoga Boulevard, Winchester Street

- 12 Mile Road

- 12 1⁄2 Mile Road—Webster Road

- 13 Mile Road

- 13 1⁄2 Mile Road—Whitcomb Avenue, Normandy Road, Beverly Road

- 14 Mile Road

- 14 1⁄2 Mile Road—Elmwood Avenue, Lincoln Street

- 15 1⁄2 Mile Road—Oak Blvd. (west of Woodward)

- 15 Mile Road—Maple Road

- 16 Mile Road—see below

- 16 1⁄2 Mile Road—Lone Pine Road, Dawson Road

- 17 Mile Road—Wattles Road

- 17 1⁄2 Mile Road—Long Lake Road (west of Woodward)

- 18 Mile Road—Long Lake Road (east of Woodward)

- 18 1⁄2 Mile Road—Westview Road, Hickory Grove Road

- 19 Mile Road—Square Lake Road

- 19 1⁄2 Mile Road—Astonwood Street (Pontiac)

- 20 Mile Road—South Boulevard, Golf Drive, Coomer Road, Cooley Lake Road, Rowe Road, Honeywell Lake Road

- 20 1⁄2 Mile Road—Elm Street (Pontiac)

- 21 Mile Road—Auburn Road/Avenue

- 22 Mile Road—Hamlin Road (east of Squirrel Road), Featherstone Road/Street (west of Squirrel), Elizabeth Lake Road (Waterford)

- 22 1⁄2 Mile Road—Curt Tower Boulevard (Pontiac), Pontiac Lake Road (Waterford)

- 23 Mile Road—Avon Road (Rochester Hills), Madison Avenue (Pontiac), Highland Road (Waterford)

- 23 1⁄2 Mile Road—Tubbs Road (Waterford), Columbia Avenue (Pontiac), Pontiac Road (Auburn Hills)

- 24 Mile Road—Hatchery Road, Walton Boulevard, University Drive (Rochester)

- 25 Mile Road—Williams Lake Road, Walton Boulevard (for a short distance before deviating a mile south), Runyon Road, Taylor Road (Auburn Hills), Tienken Road (end of the Official Metro-Detroit designation according to some sources, though disputed)

- 25 1⁄2 Mile Road—North Lake Angelus Road, Great Lakes Crossing Drive (mostly off-grid, southern end of Great Lakes Crossing Outlets property), Harmon Road

- 26 Mile Road—Mead Road, Dutton Road, Brown Road, Mann Road

- 26 1⁄2 Mile Road—Judah Road

- 27 Mile Road—Silver Bell Road, Maybee Road, Gregory Road

- 27 1⁄2 Mile Road—Snell Road, Maybee Road

- 28 Mile Road—Waldon Road, Gunn Road

- 28 1⁄2 Mile Road—Gunn Road

- 29 Mile Road—Buell Road

- 30 Mile Road—Stoney Creek Road, Clarkston Road

- 31 Mile Road—Predmore Road

- 32 Mile Road—Romeo Road

- 33 Mile Road—Brewer Road, Drahner Road

- 34 Mile Road—Mack Road, Lakeville Road

- 35 Mile Road—Frick Road

- 36 Mile Road—Noble Road

- 37 Mile Road—Oakwood Road

- 38 Mile Road—Davison Lake Road (northern border of Oakland County)

Mile roads within Macomb County

Through Macomb County, most of these road names are not carried over, and nearly all of the Mile Roads are known by their mile numbers. One notable exception is Hall Road, which is part of M‑59 and almost never referred to as 20 Mile Road. In Macomb County 16 Mile Road and Metropolitan Parkway are used interchangeably.

Note: there were some roads listed as xx-half Mile Roads, and placed in between the roads, such as 13 Mile Road, 13 1⁄2 Mile Road, 14 Mile Road, in that succession for example. Some are signed as such.

- 8 Mile Road

- 8½ Mile Road—Toepfer Drive

- 9 Mile Road

- 9½ Mile Road—Stephens Drive

- 10 Mile Road

- 10½ Mile Road—Frazho Road and Lincoln Avenue

- 11 Mile Road—I‑696 Service Drive from I‑94 to roughly Dequindre Road)

- 11½ Mile Road—Martin Road (Called "Tank Avenue" for part of its length running through the old Arsenal property between Van Dyke and Mound)

- 12 Mile Road

- 12½ Mile Road—Common Road

- 13 Mile Road (partly diverted to become Chicago Road. Old alignment is now Old 13 Mile Road, from Van Dyke Road to Chicago Road/13 Mile intersection)

- 13½ Mile Road—Masonic Boulevard (Chicago Road between Mound and Dequindre)

- 14 Mile Road

- 14½ Mile Road—Quinn Road (only exists east of Gratiot), Cottrell Road (exists east of Harper, turns east-southeast)

- 15 Mile Road

- 15½ Mile Road—Brougham Drive, Glenwood Road (between Gratiot Avenue and Harper Avenue)

- 16 Mile Road (See notes on 16 Mile Road, below)

- 16½ Mile Road (between Van Dyke Road and Dodge Park Road)

- 17 Mile Road (has been carved up and re-aligned in some parts to fit in with newer suburbs as they were built in the 1970s and 1980s)

- 18 Mile Road

- 18½ Mile Road (between Van Dyke Road and Ryan Road only)

- 19 Mile Road

- 19½ Mile Road (within Utica, MI only)

- 20 Mile Road (See notes above for 20-24 Mile Roads in Macomb County)

- 21 Mile Road—Auburn Road west of Utica (veers off-grid east of Mound Road)

- 22 Mile Road

- 23 Mile Road—Part of M‑29 east of I‑94 towards New Baltimore

- 24 Mile Road—French Road (brief segment just east of Dequindre)

- 25 Mile Road (end of the official Metro-Detroit designation)

- 26 Mile Road—Marine City Highway east of I‑94

- 27 Mile Road—Clark Road (within New Haven)

- 28 Mile Road

- 29 Mile Road

- 30 Mile Road

- 31 Mile Road

- 32 Mile Road—Division Road (within Richmond), St. Clair Road (within Romeo)

- 33 Mile Road—Clay Road

- 34 Mile Road—Woodbeck Road

- 35 Mile Road—Schoof Road

- 36 Mile Road—Dewey Road

- 37 Mile Road—McPhall Road

- 38 Mile Road—Bordman Road (northern border of Macomb County)

Mile roads within St. Clair County

Through St. Clair County, none of these mile number names are carried over, as a result, all of the Mile Roads are known by their road names.

- 25 Mile Road—Arnold Road

- 26 Mile Road—Marine City Highway

- 27 Mile Road—Springborn Road

- 28 Mile Road—Meisner Road

- 29 Mile Road—Lindsey Road

- 30 Mile Road—Puttygut Road

- 31 Mile Road—St. Clair Highway

- 32 Mile Road—Division Road (Richmond to Palms Road), Fred W. Moore Highway (Palms Road eastward)

- 33 Mile Road—Clay Road

- 34 Mile Road—Woodbeck Road, Big Hand Road

- 35 Mile Road—Crawford Road

- 36 Mile Road—Meskill Road

- 37 Mile Road—Frith Road

Mile roads within Lapeer County

The system continues uninterrupted in sequence up to 38 Mile Road, on the Macomb–Lapeer county line near Almont and Van Dyke Road (M‑53). However, although not signed as mile roads, major roads still lie at one-mile (1.6 km) intervals in Lapeer County and in fact a few major roads that start in and around the city of Flint continue east into Lapeer County.

- 38 Mile Road—Bordman Road/Davison Lake Road

- 39 Mile Road—Hough Road

- 40 Mile Road—Almont Road, St. Clair Street, General Squier Road

- 41 Mile Road—Tubspring Road

- 42 Mile Road—Dryden Road

- 43 Mile Road—Hollow Corners Road

- 44 Mile Road—Webster Road, Ross Road, Sutton Road

- 45 Mile Road—Hunters Creek Road

- 46 Mile Road—Newark Road

- 47 Mile Road—Belle River Road

- 48 Mile Road—Attica Road

- 49 Mile Road—Davison Road (west of Lapeer, eastern continuation of a major section-line road that starts in Flint); Imlay City Road (between Lapeer and Van Dyke); Weyer Road (east of Van Dyke)

- 50 Mile Road—Oregon Road (west of Lapeer); Bowers Road (east of Lapeer)

- 51 Mile Road—McDowell Road, Davis Lake Road, Haines Road, Utley Road, Muck Road, Norman Road

- 52 Mile Road—Daley Road, Armstrong Road, Turner Road

- 53 Mile Road—Coldwater Road (eastern continuation of a major section-line road in the Flint area), portions of Marathon and Flint River Roads, Mountview Road, King Road, Lyons Road, Speaker Road

- 54 Mile Road—Stanley Road (eastern continuation of a major section-line road in the Flint area), Coulter Road, Reside Road

- 55 Mile Road—Mount Morris Road (eastern continuation of a major section-line road in the Flint area), Sawdust Corners Road, Curtis Road, Martin Road, Abbott Road

- 56 Mile Road—Pyles Road, Norway Lake Road, Clear Lake Road

- 57 Mile Road—Columbiaville Road (turns southeast as Pine Street from the east and southwest as 2nd Street from the west within Columbiaville), Mott Road, Willis Road

- 58 Mile Road—Piersonville Road, Miller Lake Road (briefly), Hasslick Road, Deanville Road

- 59 Mile Road—Sister Lake Road, Barnes Lake Road, Johnson Mill Road, Martus Road, Wilcox Road

- 60 Mile Road—Howell Road, Burnside Road (part of M-90 east of Van Dyke)

- 61 Mile Road—Otter Lake Road, Tozer Road, Elm Creek Road, Brooks Road

- 62 Mile Road—Castle Road, Stiles Road

- 63 Mile Road—Elmwood Road, Dwyer Road, Peck Road

- 64 Mile Road—Barnes Road

- 65 Mile Road—Millington Road, Montgomery Road

- 66 Mile Road—Murphy Lake Road

- 67 Mile Road—Swaffer Road, Markle Road, Soper Road

- 68 Mile Road—Brown Road, Marlette Road (northern border of Lapeer County)

8 Mile Road

Locally, 8 Mile Road is considered the political and social dividing line between the city of Detroit and its northern suburbs. (It marks most of the northern boundary of both Detroit and Wayne County.) In 2002 this local notoriety was promoted to international attention, reflected in the name of Eminem's acclaimed film, 8 Mile.

16 Mile Road

The alignment for 16 Mile Road through Oakland and Macomb Counties is composed of five named roads:

- Buno Road (through Milford Township)

- Walnut Lake Road (through West Bloomfield Township)

- Quarton Road (from Inkster Road to Woodward Avenue)

- Big Beaver Road (from Woodward to Dequindre)

- Metropolitan Parkway (from Dequindre to Metro Beach Metropark)

Walnut Lake Road turns slightly southward in West Bloomfield and runs parallel to Quarton Road .5 miles (0.80 km) to the south, between Inkster and Franklin Roads. West and East Quarton Roads are disconnected slightly by Telegraph Road due to Gilbert Lake. Walnut Lake Road ends at Haggerty Road in Commerce Township and the grid-alignment of 16 Mile Road remains non-existent through much of the township. Buno Road continues this grid alignment in Milford

Addresses

With a few exceptions, one can determine which mile roads an address is between on major north–south roads north of Five Mile/Fenkell by using the formula:

- [(first two numbers of the address)-5] / 2

- Example: 34879 Gratiot Avenue [(34-5)/2]= 14.5 which indicates the address is between 14 Mile and 15 Mile roads.

In the early days of Detroit-area house numbering, surveyors calculated position on the grid of mile roads to define addresses. The resulting system, adopted in 1921 and sometimes referred to as the Detroit Edison system, generally assigns 2000 addresses to each mile. (There are often gaps in the numbering; for instance, east addresses 9000 to 10999 and north addresses 2300 to 5599 [at Ford Road] are skipped). Addresses in the Detroit area tend to be much higher than in many other major cities, with numbers in the 20000s common within the city limits and in the inner-ring suburbs. Typically, addresses of single family homes on adjacent lots on the grid system, both within Detroit and in the suburbs, are incremented by 8, 10, 12 or more rather than by 2 as is the case in most other large cities in the United States.

Addresses are generally numbered outwards from Woodward Avenue (south of McNichols Road) and John R. Street (north of McNichols) for numbers on east–west roads and from the Detroit River (east of the Ambassador Bridge), a Norfolk Southern Railway/CSX Transportation railroad line between the Ambassador Bridge and the Rouge River, the Rouge River itself north to just past Michigan Avenue in Dearborn, an imaginary line from there to the eastern end of Cherry Hill Road and Cherry Hill Road for numbers on north–south streets, with the numbers increasing the further one is from these baselines.

The highest addresses used in the Detroit system are the range 79000 to 80999, for north–south roads beyond 37 Mile Road in northern Macomb County, and from 81000 to the high 81900s in the portion of the city of Memphis that bulges about 0.5 miles (0.80 km) into St. Clair County. For many years, the Guinness World Book of Records incorrectly listed 81951 Main Street (M‑19) in Memphis as the highest street address number anywhere, but higher numbers are in use elsewhere, such as Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park at 127011 Newton B. Drury Scenic Parkway in Orick, California.

The westernmost street within the city of Detroit is Five Points Street, which is a north-south half-mile road located along the border with Redford Charter Township halfway between Telegraph and Beech-Daly Roads and runs 2.5 miles (4.0 km) north from Puritan Street to 8 Mile Road. The easternmost point of the city is located in the intersection of Mack Avenue and Kingsville Street, which is located 1 mile (1.6 km) east-southeast of Interstate 94 along the border with Grosse Pointe Farms and Grosse Pointe Woods. The city's southernmost point is within the median of Outer Drive at the intersection of the borders with Ecorse and Lincoln Park just east of Bassett Street, eight-and-a-half-blocks east-southeast of Fort Street.

Even though many suburbs also use the Detroit system, there are several that instead use their own numbering systems, including Birmingham, Ecorse, Ferndale, Lincoln Park, Mount Clemens, Pontiac, River Rouge, Trenton and Wyandotte. Royal Oak also uses a numbering system separate from Detroit's, its system has a baseline for north–south numbers at 11 Mile Road and one for east–west numbers at Main Street.

Mile roads traveling south

The grid continues south of Ford Road, although not numbered as part of the Mile Road System. None of these roads connect to Detroit. Further south and west, along the Lake Erie shoreline, and through Downriver, the roads tend to fall off the grids more often, for several reasons, including remnants of the French ribbon farms and natural features preventing straight road building, though west of Monroe, major roads, for the most part, still lie one mile (1.6 km) apart uninterrupted up to, and past, the border with the state of Ohio, which lies almost 40 1⁄2 miles (65.2 km) south of Ford Road.

- Ford Road—Zero Mile Road

- Saltz Road—South 0 1⁄2 Mile, Saltz Road west of I‑275, Marquette Avenue/Road east of I‑275 to Inkster Road, Wilson Drive east of Inkster Road.

- Cherry Hill—South 1 Mile, Dixboro to Dearborn.

- Avondale Street—South 1 1⁄2 Mile, Dearborn Heights to Westland.

- Palmer Road—South 2 Mile, Canton Township to Westland-Inkster border. Vreeland Road in Washtenaw County

- Glenwood Road—South 2 1⁄2 Mile (only within Wayne and Westland, Michigan)

- Geddes Road—South 3 Mile, Superior Township to Canton Township. Carlysle Road in Inkster and Dearborn.

- Annapolis Road—South 3 1⁄2 Mile, Wayne to Dearborn Heights (1/2 mile gap in Westland)

- Van Born Road—South 4 Mile, township border road, from Van Buren Township to Allen Park, where it ends at a trumpet interchange with M‑39 and its service drives. On the north, it borders Canton, Wayne, Westland and Dearborn Heights. On the south it borders Van Buren Township, Romulus, Taylor and Allen Park. Just before Lilly Road it falls off grid. West of that point, it's gridline is occupied by Yost, Mott, Clark and Scio Church Roads.

- Beverly Road—South 4 1⁄2 Mile (only within Van Buren Township, Romulus and Taylor)

- Ecorse Road—South 5 Mile, former M‑17. Once a major artery to the Willow Run Expressway. West of US 12 in Washtenaw County almost migrates a mile. In Ypsilanti, the alignment is followed by Cross Street, which continues westward to Ann Arbor as Packard Road and Eisenhower Boulevard.

- Champaign Street/Road—South 5 1⁄2 Mile, Taylor to Lincoln Park (side street for its entire length, off-grid east of Allen Road), Robson Road in Van Buren Township.

- Wick Road/Hartwick Highway—South 6 Mile, Romulus to Lincoln Park, divided side street in Allen Park. Ends at Vine Avenue and resumes as Hartwick Highway (despite its suffix is a residential street), merging with Minnie Street at Bailey Avenue and falls off-grid. East of I‑75 it is almost followed by the residential Rose Avenue eastward to Fort Street.

- Hildebrandt/Kinyon- South 6 1⁄2 Mile—Hildebrandt Street in Romulus, starting at Middlebelt Road which runs along the boundary of the Detroit Metro Airport, ends a mile after, Kinyon Street takes over in Taylor, but is a residential street and is interrupted several times. Midway Avenue in Allen Park also follows it twice. It is also followed by Buckingham Avenue in Lincoln Park.

- Goddard Road—South 7 Mile, Romulus to Wyandotte, falls off grid just east of I‑75. Moran Avenue takes over to River Drive while Goddard turns southeastward, running jagged to Biddle Avenue in Wyandotte.

- Brest Road—South 7 1⁄2 Mile - 2nd Street in Wyandotte to Inkster Road in Taylor. Has a few interruptions. Brest Road (west of Wyandotte); Baumey Avenue (Wyandotte)

- Northline—South 8 Mile—Northline Road (west of Wyandotte); Ford Avenue (Wyandotte). Interrupted by the Metro Airport, then west of there, meanders northwest with Wabash Street taking over just west of the CSX railroad crossing, ends at Hannan Road and becomes a service drive for I‑94.

- Superior—South 8 1⁄2 Mile—Superior Street/Road (west of Wyandotte). Almost followed by Vinewood Avenue within Wyandotte

- Eureka Road—South 9 Mile, forms southern boundary of Detroit Metropolitan Airport. Veers off-grid and becomes a boulevard between Wayne Road and just east of Merriman Road, featuring a trumpet interchange that provides access from the south along this portion. Becomes Hull Road west of the Huron River.

- Leroy Street—South 9 1⁄2 Mile—Leroy Street (west of Wyandotte); Grove Street (Wyandotte)

- Pennsylvania—South 10 Mile, township border road. Borders Wyandotte, Southgate, Taylor and Romulus on the north side and Riverview, Brownstown Township and Huron Township to the south. Becomes Bemis Road west of the Huron River.

- Prescott—South 10 1⁄2 Mile—Prescott (Huron Township); Crawford (Brownstown Township); Longsdorf Street (Riverview). Is interrupted near its western end by the former Pinnacle Race Course.

- Sibley Road—South 11 Mile, Jefferson on the Riverview/Trenton limits to Huron River Drive in New Boston. Becomes Willis Road west of the Huron River.

- Bredow Road/Avenue—South 11 1⁄2 Mile—Almost followed by Greentrees Drive in Riverview.

- King Road—South 12 Mile, Jefferson in Trenton to Vining Road in Huron Township. Becomes Judd Road west of the Huron River.

- Carter Road—South 12 1⁄2 Mile—Carter (west of Trenton); Harrison Avenue (Trenton)

- Huron Road/West Road—South 13 Mile—Huron (west of I‑275); West (east of I‑275). Becomes Dunn Road and Talladay Road west of Huron Township.

- Grix Road—South 13 1⁄2 Mile—Grix Road/Stacey Drive/Provincial Street/Marian Drive in Huron Township, Brownstown Township, Woodhaven and Trenton, respectively.

- Willow Road/Van Horn Road—South 14 Mile, Willow (west of Willow Metropark); Van Horn (east of Willow Metropark).

- Vreeland—South 15 Mile, city limit road, with Woodhaven and Trenton on the north side and Flat Rock, Brownstown Township and Gibraltar on the south side. Recently extended west of Telegraph Road. Gridline also occupied west of the Huron River by Ash Road and Arkona Road.

- Milan-Oakville Road/Oakville-Waltz Road/Will Carleton Road/Gibraltar Road—South 16 Mile (border of Wayne and Monroe County)

- Woodruff Road—South 17 Mile, Huron River Drive in Flat Rock to Jefferson in Gibraltar. Becomes Newburg Road, Colf Road and Darling Road in Monroe County.

- Grames Road/Fay Road/Carleton-Rockwood Road/Huron River Drive—South 18 Mile

- Allison Road/Scofield-Carleton Road/Nolan Road/Ready Road/Lee Road—South 19 Mile

- Hoffman Road/Ohara Road/Sigler Road—South 20 Mile

- Ostrander Road/Zink Road/Labo Road—South 21 Mile

- Day Road/Heiss Road/Toben Road/Newport Road—South 22 Mile

- Stewart Road/Buhl Road—South 23 Mile

- Post Road/Stumpier Road—South 24 Mile

- Nadeau Road—South 25 Mile

- Eggert Road/Fix Road—South 26 Mile

- Dunbar Road—South 27 Mile

- Ida West Road—South 28 Mile

- Albain Road—South 29 Mile

- Lulu Road—South 30 Mile

- Ida Center Road—South 31 Mile

- Todd Road/Stein Road—South 32 Mile

- Morocco Road/Wood Road—South 33 Mile

- Rauch Road/Cousino Road—South 34 Mile, Rauch (west of Telegraph); Cousino (east of Telegraph)

- Samaria Road/Luna Pier Road—South 35 Mile, former M-151

- Erie Road—South 36 Mile

- Temperance Road—South 37 Mile

- Dean Road—South 38 Mile

- Sterns Road—South 39 Mile

- Yankee Road/Smith Road/Lavoy Road—South 40 Mile

- State Line Road—South 40 1⁄2 Mile, southern border of Monroe County and the state of Michigan, though it falls off-grid, mostly to follow the border itself, which actually runs at an offset angle.

Similar to McNichols Road in Detroit, Wyandotte residents refer to Northline Road (south 8 Mile) as such, although it is signed as Ford Avenue within the city.

The north–south mile grid

There are many roads through Wayne, Oakland, Macomb and even Monroe, Washtenaw and Livingston counties that parallel the Michigan Meridian, creating a grid-type system. Like the east–west Mile Road System, the north–south grid roads lose cohesion to the grid in much of Detroit, the Grosse Pointes, eastern Downriver, and in the lake-filled areas of Oakland County.

Proceeding west from Lake St. Clair:

- Greater Mack Avenue—Residential street, cuts off several times between 10 and 15 Mile before becoming a steady street. Mack Avenue in Detroit.

- Little Mack Avenue—Approximately 9–16 Mile, cutting off once at 14 Mile. Gridline taken by Heydenreich Road in the northern suburbs.

- Kelly Road and Romeo Plank Road (Between Clinton River Road and roughly 24 Mile Road) Becomes diagonal at 9 Mile and remains that way to Hayes Street in Detroit.

- Garfield Road—From Utica Road in Fraser to 22 Mile Road in Macomb Township.

- Hayes Road—Although not fully contiguous, Hayes Road is a township border road through eastern Macomb County. Terminates at 28 Mile. Also continues south of 8 Mile in Detroit as Hayes Street to the large intersection of Harper, Chalmers and Hayes just near I‑94.

- Schoenherr Road - An example of a gridline road with a divided highway portion. Paved between southern terminus and 26 Mile Road. Terminates at 29 Mile.

- Hoover Road, Dodge Park Road, (Chicago Road and Maple Lane Drive connect Hoover and Dodge Park from just south of 14 Mile to 15 Mile), M‑53 Freeway, and Jewell Road. These series of roads follow the same grid line until about 29 Mile Road when Van Dyke Avenue takes over.

- Van Dyke Avenue M‑53 (Van Dyke Avenue) Runs from Jefferson Avenue in Detroit to Grindstone Road in Port Austin. Although M‑53 ends at Gratiot Avenue in Detroit, Van Dyke Avenue itself actually continues to Jefferson Avenue in Detroit, adjacent to the Detroit River. At 18-Mile Road in Sterling Heights, M‑53 splits off towards the East into a freeway, and the grid road (old M‑53) continues northward as the Van Dyke Road (also signed in some places as the Earle Memorial Highway). South of 28 Mile Road, Van Dyke begins a Northeast shift to a mile eastward and Camp Ground Road takes over to continue the grid.

- Mound Road - Originally planned to be at least partially a freeway, connecting the Davison Freeway with I‑696 and the M‑53 Freeway, hence the massive stacked interchange at I‑696. Mound Road is the Avenue due north of the Renaissance Center.

- Ryan Road—Runs from 23 Mile in Shelby Township through Sterling Heights, Warren and into Detroit before falling off the grid at Davison.

- Dequindre Road—The borderline between Oakland and Macomb Counties. Not fully contiguous, falling off the grid briefly at 26 Mile before resuming just north of 28 Mile.

- John R Road—Begins at Bloomer Park in Rochester just north of 23 Mile (Avon Rd.) and continues south to McNichols. Past that it turns to run parallel with Woodward to downtown Detroit.

- Stephenson Highway—Branches off of Rochester Road south of the Troy I‑75 Interchange. Rochester turns west before turning back south and running parallel with Stephenson. Stephenson becomes the service drive for I‑75 at 12 Mile.

- Campbell Road—Begins at 14-Mile. Runs parallel to Stephenson Highway and Rochester Road. Continues past I‑696/10 Mile Rd. as Hilton Road in Ferndale, with its southern terminus at M‑102 8 Mile Rd. North of I‑696/10 Mile Rd., the road runs in Royal Oak and Madison Heights, and it serves as the border between the two cities for most of the stretch.

- Rochester Road (north of Troy I‑75 interchange). Known as Main Street in downtown Rochester. Splits off to Stevenson Highway and turns west for a short path until it turns back parallel with Stevenson. It continues down into Royal Oak, where it ends at the Main-Crooks-Rochester interchange. Ends in Lapeer County on the Northern end. Carries the M‑150 state highway designation through Rochester Hills.

- Livernois Avenue—Discontiguous between 9 Mile & 10 Mile Roads. Known as Main Street in Royal Oak and Clawson (between its intersection with I‑696/Woodward/10 Mile and 14½ Mile Road (Elmwood Avenue)). Portion north of 14½ Mile Road signed as Livernois Road. Southward, Livernois extends past Joy Road before turning south-southeastward at Alaska Street to run parallel with Woodward and terminate at Jefferson at the Detroit River. Northward, it ends in Rochester at 26½ Mile as a dirt road. Portion running through Detroit was once known, and dually signed, as the "Avenue of Fashion"

- Dix Road/Highway—Begins at Oakwood Boulevard in Melvindale, runs just west of the Greenfield Road line through Lincoln Park and Southgate (where it becomes Dix-Toledo Highway) before turning southwestward at Northline Road.

- Allen Road—Beginning at an off-grid Greenfield in the same city that Dix starts in, Allen also continues south through Allen Park and at Goddard Road runs along the Evergreen/Cranbrook line as a city limit road with Taylor to the west and Southgate through the east, then going through Brownstown Township and Woodhaven before running parallel with Fort Street to a T-intersection with Gibraltar Road.

- Wyoming Avenue/Street, Rosewood St., Crooks Road, Old Perch Road, Lake George Road—Although disconnected by several miles, these five roads lie along the same grid alignment. Wyoming is the easternmost north–south grid road to reach the Zero Mile road (Ford Road) on the same north–south alignment. 2nd Street in Wyandotte almost follows this grid a few feet to the west.

- Meyers Rd. (sometimes incorrectly signed as "Myers")––Aligned on a half-mile line, Meyers runs from Capital St. (in Royal Oak Township) to just north of Tireman St. (1½ Mile). From Tireman south to Michigan Ave., Miller Rd. follows this gridline and then shifts to a south-southeasterly route to its terminus at Fort St.); and from just north of Capital Ave. to its terminus at 11 Mile Rd., Scotia Rd. follows this gridline.

- Schaefer Highway (Detroit and Dearborn), Coolidge Highway (River Rouge and Oakland County). Prior to Detroit's annexation of Greenfield Township, Schaefer Highway was known as Monnier Road. Although disconnected from Schaefer Highway, Gohl Road in Lincoln Park also runs along this gridline, which is also occupied by 15th Street in Wyandotte before falling off-grid (but still on a north-south alignment) at Ford Avenue.

- Greenfield Road—Township border road. Begins in Melvindale and runs north to end at 14 Mile Road. Formed the border of former Greenfield Township and Redford Township, now parts of Detroit. Less than a mile north of Greenfield's terminus at 14 Mile, this grid line continues via Adams Road, beginning at Woodward (just south of Lincoln [14½ Mile Rd.]) and runs north to approximately 1/3 mile north of Auburn Road (21 Mile), where it swings about a mile east, then runs north roughly along the Schaefer/Coolidge line to end at Stoney Creek Road (30½ Mile). This gridline is also occupied in the Downriver area by Burns Street in Lincoln Park and Southgate, Fort Street in Riverview and Trenton and Division Street in Trenton.

- Squirrel Road—Unusual for not following exactly the mile grid lines, Squirrel runs north from Wattles Road (17 Mile) along a north–south line displaced 1/4 mile east from the line of Southfield Road. Squirrel then drifts further east before ending at Silver Bell Road (27 Mile Road).

- Southfield Freeway/Road—Designated as M‑39, a limited-access freeway with service drive, for much of its length from I‑94 in Allen Park north to 9 Mile Rd. in Southfield. Follows grid beginning as Southfield Road, a surface street (but without the M‑39 designation), north of 9 Mile Road (ending at Maple Road [15 Mile]) and then south as a freeway to Michigan Ave (0 Mile Rd.), where it curves southeasterly, then southwesterly, and finally, southeasterly again (all within a stretch of less than three miles) and then continues south of I‑94 as surface street Southfield Rd. (but this time retaining its status as State Highway M‑39) to just south of its intersection with I‑75 at Fort St. before once again abandoning the M‑39 designation for the remainder of its route, ending at Jefferson Ave. and the Detroit River.

- McCann Road/Avenue/Street—Follows Southfield Road's grid line in Southgate and Brownstown Township (near Lake Erie Metropark).

- Evergreen Road south from 13½ Mile (Beverly) Rd. to Ford (0 Mile) Rd. (Evergreen swings off-grid north of 13½ Mile), where it shifts sightly to the east before terminating at Michigan Ave. Opdyke Road (pronounced by the locals as “UP-dike”) parallels the grid but just slightly to the west of it from Woodward north of Long Lake Road (which at that point is roughly 17½ Mile), then drifts further east before dumping into M‑24 (Lapeer Road) just north of Walton Boulevard (24 Mile). Pelham and Allen Roads follow Evergreen's grid from Dearborn to Gibraltar Road near Fort Street.

- Lahser Road—The center road for old Redford Township (now part of Detroit), Lahser connects with Outer Drive just south of Fenkell (5 Mile) and runs north to end at Square Lake Road (19 Mile). The name Lahser is often mispronounced, most often because of careless misreading as “Lasher”. Another common but deprecated pronunciation is “LAH-zer”. Students of Lahser High School in Bloomfield Township are quick to assert “LAH—sir” as the correct pronunciation, but many older Detroiters are equally insistent on “LAH—sher” (rhymes with "nosher"). Monroe and Racho roads follow Lahser's grid, in a discontinuous fashion, from southern Dearborn to Brownstown Township.

- Telegraph Road - US 24 follows the grid alignment from Brownstown Township to Southfield, where it strays slightly off the gridlines. Telegraph forms much of the western boundary of Detroit. The second Single-Point Urban Interchange in metro Detroit opened at Telegraph and I‑94.

- Beech Daly Road—simply Beech Road between 8 Mile and 10 Mile, where it ends; Franklin Road in Oakland County roughly corresponds to this alignment north of 11 Mile Road. Formerly known as Jim Daly Road in southern Wayne County. A short gap exists in Inkster, between Avondale Street and South River Park Drive north of Michigan Avenue.

- Inkster Road—Township border road; separates several communities, including Farmington Hills and Southfield in Oakland County (where it begins at Lone Pine [17 Mile] Rd.), and Redford Township, Livonia, Dearborn Heights, Westland, Taylor and Romulus in Wayne County (where it ends at Huron River Dr. at the minus 15 Mile Rd. mark). Runs through the city of Inkster.

- Middle Belt Road—more commonly known, and often signed, as Middlebelt Road—follows the grid line from Walnut Lake (16 Mile) Road in West Bloomfield Township. south to Huron River Driver (just south of the minus 14 Mile mark) in Huron Township, although Middlebelt itself continues north from Walnut Lake Road, winding north another four miles (6.4 km) to terminate at Orchard Lake Road.

- Merriman Road (south of 8 Mile Road), Orchard Lake Road (north of 8 Mile Road) - At its south end, Merriman leads into the Detroit Metropolitan Airport and becomes John D. Dingell Drive It resumes its grid position south of the airport. Orchard Lake Road roughly turns into Auburn Road at the Woodward intersection in Downtown Pontiac.

- Farmington Road—Major road north from Ann Arbor Trail and exists as a small, residential road through Westland and Garden City. Venoy Road serves as the major artery although at a grid position 1/4 mile east of Farmington from Hines Park south to Van Born. Vining Road resumes Farmington Road's position south of Metro Airport.

- Drake Road (north of 9 Mile Road), Wayne Road (south of Plymouth Road)

- Newburgh Road (south of 8 Mile Road), Halsted Road (north of 8 Mile Road)

- Haggerty Road—A township border road between Pontiac Trail and 6 Mile Road, Haggerty significantly deviates westward south of 6 Mile, migrating to an alignment one mile west within Canton Township. Other roads that follow the border alignment include Eckles Road, Hannan Road, Clark Road, and, in Monroe County, Exeter Road.

- Meadowbrook Road, Welch Road—Separated between 13 and 14 Mile. Haggerty follows this alignment in Canton Township

- Lilley Road—aligned on a half-mile line, Lilley forms much of the eastern border of the city of Plymouth, where it is also known as Mill Street.

- Novi Road—from 8 Mile north to 14 Mile, originally; north of 12 Mile Road, Novi Road was realigned in the 1990s to meet with Decker Road, which runs 1/2 mile to the east. Very briefly veers to the west to end at 8 Mile because there is a large bridge on 8 Mile over a railroad track where Novi Road would normally end.

- Morton-Taylor Road—In Canton Township and Martinsville Road in Van Buren and Sumpter Townships, although not connected to Novi Road or each other, follow this alignment. Morton-Taylor continues northward into Plymouth as Main Street, where it curves in downtown to meet Plymouth Road.

- Sheldon Road—Like Lilley, Sheldon Road is on a half-mile alignment, and it is a county road from 8 Mile Road in Northville to Van Born Road at the Canton/Van Buren Township border. Sheldon forms much of the western boundary of the city of Plymouth, and is one of only two exits off of M‑14 that services Plymouth. Known as Center Street between 7 Mile and 9 Mile where the road ends.

- Canton Center Road—In Canton Township, most urban development prior to the 21st century occurred east of Canton Center Road. Although originally slightly discontinuous with Belleville Road at Michigan Avenue, Canton Center Road was realigned to connect with Belleville Road. Northbound thru traffic into Plymouth Township is pushed through northeasterly on Sheldon Center Road to connect with Sheldon Road, while Canton Center continues as a side road servicing the Plymouth-Canton Educational Park. Taft Road follows this line in Novi and Northville.

- Beck Road—from Tyler Road in Van Buren Township to Potter Road in Wixom. Recently, a Single-Point Urban Interchange opened at Beck and I‑96, the first in Metro Detroit.

- Ridge Road—a largely rural route, Ridge veers off to the west significantly south of Ford Road, crossing the Wayne-Washtenaw county line and into the easternmost part of Ypsilanti. At Saltz Road, Denton Road splits form Ridge and resumes the line from Cherry Hill Road to Ecorse Road. Garfield and Wixom Roads follow this line in Oakland County.

- Napier Road—from Cherry Hill to Grand River. Napier forms part of the border between Wayne and Washtenaw Counties for the most part, though it does veer off to the west for a few miles. From I‑94 to Oakville-Waltz Road, Rawsonville Road follows the same alignment.

- Chubb Road—from 5 to 10 Mile Roads, entire length is gravel. Gottfredson Road follows the same alignment from Brookville Road to Geddes Road, paved between North Territorial Road and Plymouth-Ann Arbor Road.

- Currie Road—from 5 to 10 Mile Roads, paved from 6 to 8 Mile.

- Milford Road—Milford Road starts at 10 Mile and runs north and Northeast shortly after the intersection of Huron River Pkwy to General Motors Road near Downtown Milford and continues through Highland Township and turns into Holly road in the city of Holly. Curtis Road, which runs from 6 Mile to Plymouth-Ann Arbor Road, runs roughly along the same line, as does Prospect Road from south of Murray Lake (after winding eastward from Plymouth-Ann Arbor Road) to Grove Street just north of I-94.

- Griswold Road, Tower Road—Tower Road is gravel. Griswold runs from 8 to 10 Mile in Lyon Township and South Lyon.

- Pontiac Trail— Through some twists and turns Pointiac Trail ends in the northeast at Orchard Lake Road at the village of Orchard Lake and takes a meandering southwesterly route to New Hudson in Lyon Township to avoid the nearby shopping center and Interstate 96. This results in Pontiac Trail ending at Milford Road north of I‑96 and then continuing at a three-road intersection of Grand River, Milford and Pontiac Trail south of I‑96. Later turning south at the intersection of Silver Bell Road it goes south and through Downtown South Lyon as Lafayette Street and goes Southwest to Ann Arbor and ends at Swift Street one block north of Plymouth Rd. in Ann Arbor.

- Dixboro Road—Oakland and Livingston County line, also runs southward into Ann Arbor and Ypsilanti.

- Carpenter Road—Washtenaw County, former US 23 from M-17 in southwest Ann Arbor to Main Street in Milan. Signed as Dexter Street in Milan. Another portion of Old US 23 in Monroe County follows the alignment from Cone Road (US 23 exit 22) into Dundee. Earhart Road north of Geddes Road follows the same alignment, veering eastward between Goss Road and M-14, staggering eastward at Joy Road, and again at 6 Mile where it drifts further eastward off the grid.

Irregularities in the gridline alignment

There are some notable irregularities to the gridline system as described above. This is similar to enclaves and exclaves in terms of geographical discrepancies.

East–west

8 Mile

- Veers slightly north between Griswold and Taft Roads in Northville due to the ravine.

- Interrupted by Whitmore Lake in Livingston County. Traffic carried over Spencer, 7 Mile, East Lake Shore Drive, and Main Street.

- 8 Mile ends at the east side of Greater Mack Avenue (this segment at its east end starts at Yorktown Street's intersection with Goethe Street), with a discontinuous one-block gap to the west of that portion (land occupied by the closed Shorepointe Lane Housing Community).

- 8 Mile (proper) veers sharply onto Brys Drive (avoiding Shorepointe Lane Housing) in order to connect to Greater Mack Avenue 2 blocks of the terminus mentioned directly above this note.

9 Mile

- Interrupted east of Grand River for approximately 2 miles until west of route 5 in Farmington. 9 Mile diverts south into Orchard Lake Rd.

10 Mile

- Interrupted in much of the Farmington area, where its gridline is occupied by Grand River Avenue.

11 Mile

- Approaching Telegraph Road from the East, veers north to avoid the Telegraph/696/Lodge/Northwestern Highway interchange.

- Approaching Telegraph Road from the West, veers south and becomes Franklin Road once it's off the grid line.

- Ends at Farmington Road from the East and continues as Brittany Drive, a residential street that meanders south and west to a dead end.

- Ends at Drake Road from the West. Crossing Drake continues as Pleasant Valley Road, a residential street that curves south.

- Becomes Eleven Mile Court crossing Halsted Road from the east. This ends at a cul-de-sac where Saratoga Circle exits north.

- Breaks into two parts east of Meadowbrook Road at the 96/696/M5 interchange, where it discontinues westwaRoad

- Ends at Town Center Drive from the east, is contiguous with Ingersol Drive in the Novi Town Center shopping plaza.

- Ends at Whipple and Creek Crossing roads, from the west, west of Novi Road

- Ends at a T junction with Wixom Road, from the east.

- Continues from Napier Road to Johns Road

- Ends at Haas Lake Road from the west.

- Approaching Dixboro Road from the east, it veers north and ends, continuing as Dixboro.

14 Mile

- Interrupted between Evergreen and Southfield Roads in the Birmingham and Beverly Hills area.

Mutual

This section covers irregularities involving areas where an east–west and north–south road would otherwise intersect. All roads involved with a domino effect will be involved in a single summary.

- In eastern Washtenaw County, M‑14 runs diagonally. Because of this, it causes other irregularities. From the west, Warren Road falls off the grid to run along the westbound side of the freeway and T's with Curtis Road. Ford and Plymouth roads physically cross each other near M‑14. Ford Road also has an indigenous dirt road segment between Dixboro and Earhart Roads.

- 6 Mile/McNichols in Detroit is interrupted between French Road and Outer Drive/Conner Street by Coleman A. Young Airport. East of that, starting at Gunston Street, it meanders to follow the Woodward grid used throughout Detroit and ends at Gratiot Avenue near Schoenherr Street. Because of this, Sauer Street follows the same grid to Waltham Street.

- Orchard Lake Road physically continues as 9 Mile Road at the Grand River Avenue junctions just north of the M‑5 freeway where it curves to have an overpass perpendicular to the freeway whose angle causes other irregularities. From the west, 9 Mile physically continues as Folsom Road (along the eastbound side of the freeway) with a slip ramp to the eastbound side (partial interchange at Farmington Road with east exit and east entrance only); and to the South of Orchard Lake has a sign that indicates the direction of 9 Mile. 9 Mile Road also has an indigenous dirt road segment between Grand River and Freedom road (along the westbound side of the freeway).

- At Shiawassee Road, Farmington Road and 10 Mile Road physically end at T-junctions (10 Mile ending at Farmington north of Shiawassee, Farmington ending at Shiawassee; north T to the west, south T to the east). East of Halsted Road, Grand River physically continues as 10 Mile. Halsted has 2 T-junctions at Grand River (north to the west, south to the east) with an overpass of M‑5 between the T-junctions. South of the west T junction, Halsted has a slip ramp onto eastbound M‑5; also westbound M‑5 has an entrance toward northbound Halsted road.

See also

References

- ↑ Lingeman, Stanley D. (April 6, 2001). Michigan Highway History Timeline 1701–2001: 300 Years of Progress. Lansing, MI: Library of Michigan. p. 1. OCLC 435640179.

- ↑ World Trade Center Detroit/Windsor. "Regional Advantages for International Business" (PDF). World Trade Center Detroit/Windsor. Retrieved September 3, 2007.

- ↑ Michigan Department of Transportation (April 17, 2002). "Why Doesn't Michigan Have Toll Roads?". Michigan Department of Transportation. Retrieved September 5, 2007.

- ↑ Bessert, Christopher J. (January 31, 2009). "Early Willow Run, Detroit Industrial & Edsel Ford Expressways". Michigan Highways. Retrieved January 30, 2010.

- ↑ Baulch, Vivian M. (June 13, 1999). "Woodward Avenue, Detroit's Grand Old 'Main Street'". The Detroit News. Retrieved January 31, 2010.

- ↑ Detroit 300 Conservancy (2006). "Photograph of Point of Origin medallion". Detroit 300 Conservancy. Archived from the original (JPG) on July 15, 2006.

- ↑ Detroit 300 Conservancy (2006). "Campus Martius Park site plan". Detroit 300 Conservancy.

- ↑ Michigan Legislature (2001). "Michigan Memorial Highway Act (Excerpt) Act 142 of 2001, 250.1098 Rosa Parks Memorial Highway". Legislative Council, State of Michigan. Retrieved August 18, 2006.

- ↑ Greenwood, Tom (November 1, 2002). "Ribbon Cutting Opens New Road". The Detroit News.

Further reading

- Cantor, George (2005). Detroit: An Insiders Guide to Michigan. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-03092-2.

- Fisher, Dale (1994). Detroit: Visions of the Eagle. Grass Lake, MI: Eyry of the Eagle Publishing. ISBN 0-9615623-3-1.

- —— (2005). Southeast Michigan: Horizons of Growth. Grass Lake, MI: Eyry of the Eagle Publishing. ISBN 1-891143-25-5.

External links

- Detroit's "Mile" Roads (History Detroit 1701–2001)

- Rand McNally: The Road Atlas 2006 (Canada, USA, Mexico)