Right to petition in the United States

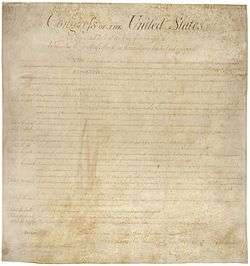

In the United States the right to petition is guaranteed by the First Amendment to the United States Constitution, which specifically prohibits Congress from abridging "the right of the people...to petition the Government for a redress of grievances".

Although often overlooked in favor of other more famous freedoms, and sometimes taken for granted,[1] many other civil liberties are enforceable against the government only by exercising this basic right.[2] The right to petition is regarded as fundamental in some republics, such as the United States, as a means of protecting public participation in government.[1]

Historic roots

The American right of petition is derived from British precedent. In Blackstone's Commentaries, Americans in the Thirteen Colonies read that "the right of petitioning the king, or either house of parliament, for the redress of grievances" was a "right appertaining to every individual".[3]

In 1776, the Declaration of Independence cited King George's perceived failure to redress the grievances listed in colonial petitions, such as the Olive Branch Petition of 1775, as a justification to declare independence:

In every stage of these Oppressions We have Petitioned for Redress in the most humble terms: Our repeated Petitions have been answered only by repeated injury. A Prince, whose character is thus marked by every act which may define a Tyrant, is unfit to be the ruler of a free people.[4]

Historically, the right can be traced back[2] to English documents such as Magna Carta, which, by its acceptance by the monarchy, implicitly affirmed the right, and the later Bill of Rights 1689, which explicitly declared the "right of the subjects to petition the king".[5]

First use

The first[6] significant exercise and defense of the right to petition within the U.S. was to advocate the end of slavery by petitioning Congress in the mid-1830s, including 130,000 such requests in 1837 and 1838.[7] In 1836, the House of Representatives adopted a gag rule that would table all such anti-slavery petitions.[7] John Quincy Adams and other Representatives eventually achieved the repeal of this rule in 1844 on the basis that it was contrary to the right to petition the government.[7]

Scope

While the prohibition of abridgment of the right to petition originally referred only to the federal legislature (the Congress) and courts, the incorporation doctrine later expanded the protection of the right to its current scope, over all state and federal courts and legislatures and the executive branches of the state[8] and federal governments. The right to petition includes under its umbrella the right to sue the government,[9] and the right of individuals, groups and possibly corporations to lobby the government.

Some litigants have contended that the right to petition the government includes a requirement that the government listen to or respond to members of the public. This view was rejected by the United States Supreme Court in 1984:

- "Nothing in the First Amendment or in this Court's case law interpreting it suggests that the rights to speak, associate, and petition require government policymakers to listen or respond to communications of members of the public on public issues."[10]

See also Smith v. Arkansas State Highway Employees, where the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the Arkansas State Highway Commission's refusal to consider employee grievances when filed by the union, rather than directly by an employee of the State Highway Department, did not violate the First Amendment to the United States Constitution.[11]

Restrictions

The law of South Dakota prohibits sex offenders from circulating petitions, carrying a maximum potential sentence of one year in jail and a $2,000 fine.[12]

Circulation of a petition by a prisoner in Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) is a prohibited act under 28 C.F.R. 541.3,[13][14] and is punishable by solitary confinement.

References

- 1 2 Porter, Lori. "Petition - SLAPPs". First Amendment Center.

- 1 2 Newton, Adam; Ronald K.L. Collins. "Petition - Overview". First Amendment Center.

- ↑ "Blackstone's Commentaries on the Laws of England". The Avalon Project at Yale Law School.

- ↑ Quote from the Declaration of Independence. Full text available at "The Declaration of Independence: A Transcription". The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- ↑ Quote from Bill of Rights 1689. Full text available at "English Bill of Rights 1689". The Avalon Project at Yale Law School.

- ↑ Kilman, J. & Costello, G. (Eds). "Analysis and Interpretation of the Constitution, 2002 ed. - First Amendment – Religion and Expression" (PDF). Congressional Research Service.

- 1 2 3 "Struggles over Slavery: The "Gag" Rule". The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- ↑ "The Right to Petition". Illinois First Amendment Center. Archived from the original on April 11, 2013.

- ↑ Newton, Adam. "Petition - Right to sue". First Amendment Center. Archived from the original on March 24, 2011.

- ↑ O'Connor, Sandra Day. "Minnesota Board for Community Colleges v. Knight, 465 U.S. 271 (1984).". Justia.

- ↑ 441 U.S. 463 (1979).

- ↑ Cook, Andrea J. (15 May 2013). "Sex offender accused of illegally circulating petitions". Rapid City Journal.

- ↑ "Prison Labor and the Thirteenth Amendment". Prison Law Blog. 16 December 2010.

- ↑ Duamutef v. O’Keefe, 98 F.3d 22 (2d Cir. 1996)