Bran

Bran, also known as miller's bran,[1] is the hard outer layers of cereal grain. It consists of the combined aleurone and pericarp.

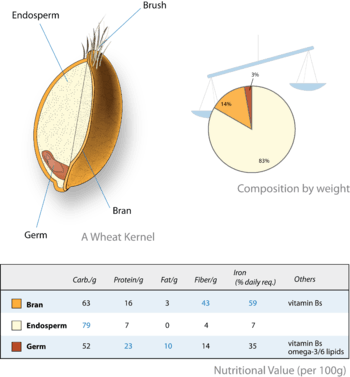

Along with germ, it is an integral part of whole grains, and is often produced as a byproduct of milling in the production of refined grains. When bran is removed from grains, the grains lose a portion of their nutritional value. Bran is present in and may be in any cereal grain, including rice, corn (maize), wheat, oats, barley, rye and millet. Bran is not the same as chaff, coarser scaly material surrounding the grain but not forming part of the grain itself.

Bran is particularly rich in dietary fiber and essential fatty acids and contains significant quantities of starch, protein, vitamins, and dietary minerals. It is also a source of phytic acid, an antinutrient that prevents nutrient absorption.

The high oil content of bran makes it subject to rancidification, one of the reasons that it is often separated from the grain before storage or further processing. Bran is often heat-treated to increase its longevity.

Composition

| Nutrients (%) | Wheat | Rye | Oat | Rice | Barley |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbohydrates w/o starch | 45–50 | 50–70 | 16–34 | 18–23 | 70–80 |

| starch | 13–18 | 12–15 | 18–45 | 18–30 | 8–11 |

| proteins | 15–18 | 8–9 | 13–20 | 15–18 | 11–15 |

| fats | 4–5 | 4–5 | 6–11 | 18–23 | 1–2 |

Rice bran

Rice bran is a byproduct of the rice milling process (the conversion of brown rice to white rice), and it contains various antioxidants that impart beneficial effects on human health.[2] A major rice bran fraction contains 12%-13% oil and highly unsaponifiable components (4.3%). This fraction contains tocotrienols (a form of vitamin E), gamma-oryzanol and beta-sitosterol; all these constituents may contribute to the lowering of the plasma levels of the various parameters of the lipid profile. Rice bran also contains a high level of dietary fibres (beta-glucan, pectin and gum). In addition, it also contains ferulic acid, which is also a component of the structure of nonlignified cell walls. However, some research suggests there are levels of inorganic arsenic (a toxin and carcinogen) present in rice bran. One study found the levels to be 20% higher than in drinking water.[3] Other types of bran (derived from wheat, oat or barley) contain less arsenic than rice bran, and are just as nutrient-rich.[4]

Uses

Bran is often used to enrich breads (notably muffins) and breakfast cereals, especially for the benefit of those wishing to increase their intake of dietary fiber. Bran may also be used for pickling (nukazuke) as in the tsukemono of Japan. In Romania and Moldova, the fermented wheat bran is usually used when preparing borș soup.

Rice bran in particular finds many uses in Japan, where it is known as nuka (糠; ぬか). Besides using it for pickling, Japanese people also add it to the water when boiling bamboo shoots, and use it for dish washing. In Kitakyushu City, it is called jinda and used for stewing fish, such as sardine. Rice bran and rice bran oil are also widely used in Japan as a natural beauty treatment. The high levels of oleic acid makes it particularly well absorbed by human skin, and it contains over 100 known vitamins, minerals and antioxidants, including gamma oryzanol, which is believed to impact pigment development.

In Myanmar, rice bran, called phwei-bya, is mixed with ash and used as a traditional detergent for washing dishes. Rice bran is also stuck to commercial ice blocks to hinder them from melting. It is also burned for fuel for rice mills in the rice growing regions of the Irrawaddy delta. Bran oil may be also extracted for use by itself for industrial purposes (such as in the paint industry), or as a cooking oil, such as rice bran oil. Japan has considered rice bran to a valuable resource since ages and extracted oil out of it and it is popularly known as heart oil. Also it is emerging as a popular cooking oil in Asian countries, especially for shallow and deep frying application.[5]

Bran was found to be the most successful slug deterrent by BBC's TV programme, Gardeners' World. It is a common substrate and food source used for feeder insects, such as mealworms and waxworms. Wheat bran has also been used for tanning leather since at least the 16th century.[6]

Brewing

George Washington had a recipe for small beer involving bran, hops, and molasses.[7]

Stability

It is common practice to heat-treat bran with the intention of slowing undesirable rancidification. However, a very detailed 2003 study of heat-treatment of oat bran found a complex pattern whereby increasingly intense heat treatment reduced the development of hydrolitic rancidity and bitterness with time, but increased oxidative rancidity. The authors recommended that heat treatment should be sufficient to achieve selective lipase inactivation, but not so much as to render the polar lipids oxidisable upon prolonged storage.[8]

See also

References

- ↑ "Wheat Bran". Spiritfoods. 2012. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ↑ Barron, Jon (21 September 2010). "Black Rice Bran, the Next Superfood?". Baseline of Health Foundation. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ↑ "Inorganic Arsenic in Rice Bran and Its Products Are an Order of Magnitude Higher than in Bulk Grain - Environmental Science & Technology (ACS Publications)". Pubs.acs.org. 21 August 2008. Retrieved 9 February 2010.

- ↑ "Superfood rice bran contains arsenic - environment - 22 August 2008 - New Scientist". Environment.newscientist.com. Retrieved 9 February 2010.

- ↑ "what is rice bran oil". AP refinery.

- ↑ Rossetti, Gioanventura (1969). the plictho. Massachusetts: The Massachusetts Institute of Technology. pp. 159–160. ISBN 0262180308.

- ↑ George Washington (1757), "To make Small Beer", George Washington Papers. New York Public Library Archive.

- ↑ Lehtinen, Pekka; Kiiliäinen, Katja; Lehtomäki, Ilkka; Laakso, Simo (2003). "Effect of Heat Treatment on Lipid Stability in Processed Oats". Journal of Cereal Science. 37 (2): 215–221. doi:10.1006/jcrs.2002.0496. ISSN 0733-5210. See figure 1 in particular