Rhode Island in the American Civil War

|

|

Union states in the American Civil War |

|---|

|

|

| Border states |

| Dual governments |

| Territories and D.C. |

The state of Rhode Island during the American Civil War, as with all of New England, remained loyal to the Union. Rhode Island furnished 25,236 fighting men to the Union Army, of which 1,685 died.[1] On the home front, Rhode Island, along with the other northern states, used its industrial capacity to supply the Union Army with the materials it needed to win the war. Rhode Island's continued growth and modernization led to the creation of an urban mass transit system, and improved health and sanitation programs.

Rhode Island during the war

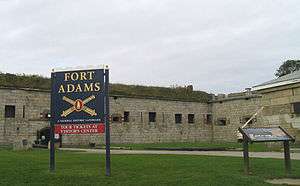

During the war, Fort Adams near Newport was used temporarily as the United States Naval Academy. In May 1861, the Academy was moved to Newport from Annapolis, Maryland, due to concerns about the political sympathies of the Marylanders, many of which were suspected of being supporters of the breakaway Confederate States of America. In September, the Academy moved to the Atlantic House hotel in Newport and remained there for the rest of the war.[2]

In 1862 Fort Adams became the headquarters and recruit depot for the 15th U.S. Infantry Regiment. This regiment, along with several others, had an organization in which the regiment had three eight company battalions. The 3rd Battalion of the 15th Infantry was organized at the fort in March 1864.[2]

The USS Rhode Island was a side-wheel steamer commissioned in 1861 for the Union Navy. It served to intercept blockade runners in the West Indies and was later a part of the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron.[3]

Notable leaders from Rhode Island

Politics

U.S. Senator Henry B. Anthony, a former governor born in Coventry, was a powerful newspaper owner and staunch advocate of the policies of President Lincoln during the Civil War. The other Senator from Rhode Island, Samuel G. Arnold of Providence, was also a Republican; he served in the Union Army until 1862 when he was elected to fill the vacancy caused by the resignation of James F. Simmons.

Rhode Island's early war governor, William Sprague, accompanied a detachment of state troops in the First Battle of Bull Run on July 21, 1861. He declined a commission as a brigadier general and remained in office. In 1862, he attended the Loyal War Governors' Conference in Altoona, Pennsylvania, which ultimately backed Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation and the Union war effort. After failing to be re-elected as governor, he was elected as a U.S. Senator to replace Arnold, taking office in 1863 and serving into Reconstruction. During the war, Sprague married Kate Chase, daughter of Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase.[4]

On March 4, 1863, Sprague became a United States Senator was replaced as governor by prominent businessman and Lieutenant Governor William C. Cozzens. Cozzens left office in May when he was succeeded by Governor James Y. Smith who led Rhode Island during the last two years of the war.[5]

Union Army

Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside, an antebellum arms manufacturer, politician, and general in the Rhode Island state militia, was perhaps the most influential Rhode Island army officer. He rose to command of the Army of the Potomac before his disastrous defeat at the Battle of Fredericksburg in December 1862. He later commanded the Department of the Ohio as well as the IX Corps. He star-crossed field duty ended during the Siege of Petersburg with another fiasco for which he took the blame, the Battle of the Crater.[6]

Maj. Gen. Silas Casey of East Greenwich led a division in the Army of the Potomac during the 1862 Peninsula Campaign that suffered heavy losses at Battle of Seven Pines facing George Pickett's brigade. He wrote the three-volume System of Infantry Tactics, including Infantry Tactics volumes I and II, published in August 1862 and Infantry Tactics for Colored Troops, published in March 1863. The manuals were used by both sides during the Civil War.[7][8]

Isaac P. Rodman commanded the 3rd Division of the IX Corps during the Maryland Campaign. He led the efforts to take Turner's Gap during the Battle of South Mountain in September 1862. A few days later, he was mortally wounded at the Antietam defending against a counterattack by Confederates under A.P. Hill.[9]

Brig. Gen. Richard Arnold, the son of Rhode Island governor and United States congressman Lemuel Arnold, was the Chief of Artillery for the Department of the Gulf. His guns helped force the surrender of two important Confederate towns—Mobile, Alabama, and Port Hudson, Louisiana.[10]

Zenas Bliss of Johnston led an infantry brigade in the IX Corps during the Siege of Petersburg. After the war, he was a recipient of the Medal of Honor for gallantry at Fredericksburg.[11] Another officer who made a significant contribution was George S. Greene of Apponaug, who spearheaded the defense of the Union right flank at Culp's Hill during the Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863. At the very end of the war, Greene was in command of the 3rd Brigade in Absalom Baird's 3rd Division, XIV Corps, and participated in the capture of Raleigh and the pursuit of Gen. Joseph E. Johnston's army until its surrender.[12]

Brig. Gen. Thomas W. Sherman of Newport commanded the defenses of New Orleans before taking command of a division in Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks's army, which he led into action at the Siege of Port Hudson, where he was severely wounded, leading to the amputation of his leg and consignment to desk duty for the rest of the war.[13] Frank Wheaton of Providence led first a brigade and then a division in the Army of the Potomac, seeing action in a number of major actions, including the Overland Campaign and the Siege of Petersburg. His men were hurried by train to Washington, D.C., in time to help repel Jubal Early's raid on the capital in the summer of 1864.[14]

Union Navy

William Rogers Taylor was Fleet Captain of the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron in 1863. He participated in attacks on the Confederate fortifications protecting Charleston, South Carolina. He then commanded the steam sloop Juniata during 1864-65 and took part in the operations that led to the capture of Fort Fisher, North Carolina.[15]

See also

Further reading

- Dyer, Frederick H., A Compendium of the War of Rebellion: Compiled and Arranged From Official Records of the Federal and Confederate Armies, Reports of the Adjutant Generals of the Several States, The Army Registers and Other Reliable Documents and Sources, Des Moines, Iowa: Dyer Publishing, 1908 (reprinted by Morningside Books, 1978), ISBN 978-0-89029-046-0.

- Grandchamp, Robert. Rhode Island and the Civil War: Voices from the Ocean State (2012) excerpt

- Gryzb, Frank L. Hidden History of Rhode Island and the Civil War (2013) excerpt

- Gryzb, Frank L. Rhode Island's Civil War Hospital: Life and Death at Portsmouth Grove, 1862-1865 (2012) excerpt

- Miller, Richard F. ed. States at War, Volume 1: A Reference Guide for Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont in the Civil War (2013) excerpt

- Williams, Frank J. and Patrick T. Conley. The Rhode Island Home Front in the Civil War Era (2013) excerpt

Notes

- ↑ Dyer's Compendium

- 1 2 Fort Adams official website

- ↑ This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships.

- ↑ United States Congress. "SPRAGUE, William (id: S000747)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- ↑ Sobel, Robert and John Raimo. Biographical Directory of the Governors of the United States, 1789-1978. Greenwood Press, 1988. ISBN 0-313-28093-2.

- ↑ Eicher, pp. 155-56.

- ↑

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Wilson, James Grant; Fiske, John, eds. (1891). "article name needed". Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Wilson, James Grant; Fiske, John, eds. (1891). "article name needed". Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.

- ↑ Casey Biography from US Regulars Archive

- ↑ Warner, p.

- ↑ Rhode Island Civil War Round Table bio of Arnold

- ↑ Bliss, Zenas Randall; edited by Thomas T. Smith, et al. (2007). The Reminiscences of Major General Zenas R. Bliss, 1854-1876: from the Texas frontier to the Civil War and back again. Texas State Historical Association. ISBN 978-0-87611-226-7. Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help) - ↑ Motts, pp. 63-75.

- ↑ Eicher

- ↑ Eicher, Warner

- ↑

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the Naval History & Heritage Command.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the Naval History & Heritage Command.