Finland

| Republic of Finland |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Anthem: Maamme (Finnish) Vårt land (Swedish) "Our Land" |

||||||

![Location of Finland (dark green)– in Europe (green & dark grey)– in the European Union (green) – [Legend]](../I/m/EU-Finland.svg.png) Location of Finland (dark green) – in Europe (green & dark grey) |

||||||

| Capital and largest city | Helsinki 60°10′N 024°56′E / 60.167°N 24.933°E | |||||

| Official languages | ||||||

| Recognised regional languages | Sami (0.04%) | |||||

| Demonym | ||||||

| Government | Unitary parliamentary constitutional republic[1] | |||||

| • | President | Sauli Niinistö | ||||

| • | Prime Minister | Juha Sipilä | ||||

| Legislature | Eduskunta | |||||

| Formation | ||||||

| • | Autonomy within Russia |

29 March 1809 | ||||

| • | Independence from the Russian SFSR |

6 December 1917 | ||||

| • | First recognized by the Russian SFSR |

4 January 1918 | ||||

| • | Joined the European Union | 1 January 1995 | ||||

| Area | ||||||

| • | Total | 338,424 km2 (64th) 130,596 sq mi |

||||

| • | Water (%) | 10 | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| • | July 2016 estimate | 5,488,543[2] (113th) | ||||

| • | 2015 official | 5,487,308[3] | ||||

| • | Density | 16/km2 (201st) 41/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2016 estimate | |||||

| • | Total | $234.578 billion[4] | ||||

| • | Per capita | $42,654[4] | ||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2016 estimate | |||||

| • | Total | $234.578 billion[4] | ||||

| • | Per capita | $41,690[4] | ||||

| Gini (2014) | 25.6[5] low · 6th |

|||||

| HDI (2014) | very high · 24th |

|||||

| Currency | Euro (€) (EUR) | |||||

| Time zone | EET (UTC+2) | |||||

| • | Summer (DST) | EEST (UTC+3) | ||||

| Date format | dd.mm.yyyy | |||||

| Drives on the | right | |||||

| Calling code | +358 | |||||

| Patron saint | St Henry of Uppsala | |||||

| ISO 3166 code | FI | |||||

| Internet TLD | .fia | |||||

| a. | The .eu domain is also used, as it is shared with other European Union member states. | |||||

Finland (![]() i/ˈfɪnlənd/; Finnish: Suomi [suomi]; Swedish: Finland [ˈfɪnland]), officially the Republic of Finland,[7] is a sovereign state in Northern Europe. A peninsula with the Gulf of Finland to the south and the Gulf of Bothnia to the west, the country has land borders with Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east. Estonia is south of the country across the Gulf of Finland. Finland is situated in the geographical region of Fennoscandia, which also includes Scandinavia. Finland's population is 5.5 million (2014), staying roughly on the same level over the past two decades. The majority of the population is concentrated in the southern region.[8] In terms of area, it is the eighth largest country in Europe and the most sparsely populated country in the European Union.

i/ˈfɪnlənd/; Finnish: Suomi [suomi]; Swedish: Finland [ˈfɪnland]), officially the Republic of Finland,[7] is a sovereign state in Northern Europe. A peninsula with the Gulf of Finland to the south and the Gulf of Bothnia to the west, the country has land borders with Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east. Estonia is south of the country across the Gulf of Finland. Finland is situated in the geographical region of Fennoscandia, which also includes Scandinavia. Finland's population is 5.5 million (2014), staying roughly on the same level over the past two decades. The majority of the population is concentrated in the southern region.[8] In terms of area, it is the eighth largest country in Europe and the most sparsely populated country in the European Union.

Finland is a parliamentary republic with a central government based in the capital Helsinki, local governments in 317 municipalities,[9] and an autonomous region, the Åland Islands. Over 1.4 million people live in the Greater Helsinki metropolitan area, which produces a third of the country's GDP. From the late 12th century, Finland was an integral part of Sweden, a legacy reflected in the prevalence of the Swedish language and its official status. In the spirit of the notion of Adolf Ivar Arwidsson (1791–1858), "we are not Swedes, we do not want to become Russians, let us therefore be Finns", the Finnish national identity started to become established. Nevertheless, in 1809, Finland was incorporated into the Russian Empire as the autonomous Grand Duchy of Finland. In 1906, Finland became the second nation in the world to give the right to vote to all adult citizens and the first in the world to give all adult citizens the right to run for public office.[10][11] Following the 1917 Russian Revolution, Finland declared itself independent.

In 1918, the fledgling state was divided by civil war, with the Bolshevik-leaning "Reds" supported by the equally new Soviet Russia, fighting the "Whites", supported by the German Empire. After a brief attempt to establish a kingdom, the country became a republic. During World War II, the Soviet Union sought repeatedly to occupy Finland, with Finland losing parts of Karelia, Salla and Kuusamo, Petsamo and some islands, but retaining independence. Finland joined the United Nations in 1955 and established an official policy of neutrality. The Finno-Soviet Treaty of 1948 gave the Soviet Union some leverage in Finnish domestic politics during the Cold War era. Finland joined the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in 1969, the NATO Partnership for Peace on 1994,[12] the European Union in 1995, the Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council in 1997,[12] and finally the Eurozone at its inception, in 1999.

Finland was a relative latecomer to industrialization, remaining a largely agrarian country until the 1950s. It rapidly developed an advanced economy while building an extensive Nordic-style welfare state, resulting in widespread prosperity and one of the highest per capita incomes in the world.[13] However, Finnish GDP growth has been negative in 2012-2014 (-0,698% to -1,426%), with a preceding nadir of −8% in 2009.[14] Finland is a top performer in numerous metrics of national performance, including education, economic competitiveness, civil liberties, quality of life, and human development.[15][16][17][18] In 2015, Finland was ranked first in the World Human Capital[19] and the Press Freedom Index, and as the most stable country in the world during 2011-2016 in the Fragile States Index,[20] and second in the Global Gender Gap Report.[21] A large majority of Finns are members of the Evangelical Lutheran Church,[22] though freedom of religion is guaranteed under the Finnish Constitution.

Etymology

The first known written appearance of the name Finland is thought to be on three rune-stones. Two were found in the Swedish province of Uppland and have the inscription finlonti (U 582). The third was found in Gotland, in the Baltic Sea. It has the inscription finlandi (G 319) and dates from the 13th century.[23] The name can be assumed to be related to the tribe name Finns, which is mentioned first known time AD 98 (disputed meaning).

Suomi

The name Suomi (Finnish for "Finland") has uncertain origins, but a candidate for a source is the Proto-Baltic word *źemē, meaning "land". In addition to the close relatives of Finnish (the Finnic languages), this name is also used in the Baltic languages Latvian and Lithuanian. Alternatively, the Indo-European word *gʰm-on "man" (cf. Gothic guma, Latin homo) has been suggested, being borrowed as *ćoma. The word originally referred only to the province of Finland Proper, and later to the northern coast of Gulf of Finland, with northern regions such as Ostrobothnia still sometimes being excluded until later. Earlier theories suggested derivation from suomaa (fen land) or suoniemi (fen cape), and parallels between saame (Sami, a Finno-Ugric people in Lapland), and Häme (a province in the inland) were drawn, but these theories are now considered outdated.[24]

Concept

In the 12th and 13th centuries, the term "Finland" mostly referred to the area around Turku (Åbo), a region that later became known as Finland Proper, while the other parts of the country were called Tavastia and Karelia, but which could also sometimes be collectively referred to as "Österland" (compare Norrland). (Medieval politics concerned tribes such as the Finns, the Tavastians, and the Karelians more than geographical boundaries.)

In the 15th century, "Finland" became a common name for the whole land area to the east of the Bothnian Sea, possibly even including Åland, when the archipelago was seen as belonging to Åbo (Turku). What the term actually refers to can vary between sources, additionally, the boundaries to the east and the north were not exact. A sort of establishment of Finland as a united entity, if only in name, was made when John III of Sweden called his duchy the "grand duchy of Finland" (about 1580), as a strategy to meet the claims of the Russian tsar. The term became part of the title of the King of Sweden but had little practical meaning. The Finnish land area had the same standing as the area to the west of the Bothnian Sea, and the Finnish part of the realm had the same representation in the parliament as the western part. In 1637, Queen Christina named Per Brahe the Younger Governor General of Finland, Åland, and Ostrobothnia (other parts of Sweden had also had governor generals).

The modern boundaries of Finland actually came into existence only after the end of Sweden-Finland. What was signed over to Russia in 1809 was not so much "Finland" as six counties, Åland, and a small part of Västerbotten County. The boundary between the new Grand Duchy of Finland and the remaining part of Sweden could have been drawn along the river Kemijoki, the boundary at the time between Västerbotten County and Österbotten County (Ostrobothnia) — as proposed by the Swedes in the peace negotiations — or along the river Kalix, thereby including the Finnish-speaking part of Meänmaa — as proposed by the Russians. The actual boundary, which followed the Torne River and the Muonio River to the fells Saana and Halti in the northwest, was a compromise. The area it delineated was to become what was represented by the concept of Finland — at least after Tsar Alexander I of Russia permitted the parts of Finland located to the east of the Kymi River, which were conquered by Russia in 1721 and 1743, called "Old Finland", to be administratively included in "New Finland" in 1812.

History

Prehistory

According to archaeological evidence, the area now comprising Finland was settled at the latest around 8500 BCE during the Stone Age as the ice sheet of the last ice age receded. The artifacts the first settlers left behind present characteristics that are shared with those found in Estonia, Russia, and Norway.[25] The earliest people were hunter-gatherers, using stone tools.[26] The first pottery appeared in 5200 BCE, when the Comb Ceramic culture was introduced.[27] The arrival of the Corded Ware culture in southern coastal Finland between 3000 and 2500 BCE may have coincided with the start of agriculture.[28] Even with the introduction of agriculture, hunting and fishing continued to be important parts of the subsistence economy.

The Bronze Age (1500–500 BCE) and Iron Age (500 BCE–1200 CE) were characterised by extensive contacts with other cultures in the Fennoscandian and Baltic regions. There is no consensus on when Uralic languages and Indo-European languages were first spoken in the area of contemporary Finland. During the first millennium AD, early Finnish was spoken in agricultural settlements in southern Finland, whereas Sámi-speaking populations occupied most parts of the country. Although distantly related, the Sami are a different people that retained the hunter-gatherer lifestyle longer than the Finns. The Sami cultural identity and the Sami language have survived in Lapland, the northernmost province, but the Sami have been displaced or assimilated elsewhere.

Swedish era

_en2.png)

Dark green: Sweden proper, as represented in the Riksdag of the Estates. Other greens: Swedish dominions and possessions.

As a part of Northern Crusades, Swedish kings established their rule in Finland gradually during 12th and 13th centuries with first, second and third crusade against Finns proper, Tavastians and Karelians. Swedish-speaking settlers colonized the coastal regions during the Middle Ages. In the 17th century, Swedish became the dominant language of the nobility, administration, and education; Finnish was chiefly a language for the peasantry, clergy, and local courts in predominantly Finnish-speaking areas.

During the Protestant Reformation, the Finns gradually converted to Lutheranism.[29] In the 16th century, Mikael Agricola published the first written works in Finnish. The first university in Finland, The Royal Academy of Turku, was established in 1640. Finland suffered a severe famine in 1696–1697, during which about one third of the Finnish population died,[30] and a devastating plague a few years later. In the 18th century, wars between Sweden and Russia twice led to the occupation of Finland by Russian forces, times known to the Finns as the Greater Wrath (1714–1721) and the Lesser Wrath (1742–1743).[30] It is estimated that almost an entire generation of young men was lost during the Great Wrath, due namely to the destruction of homes and farms, and to the burning of Helsinki.[31] By this time Finland was the predominant term for the whole area from the Gulf of Bothnia to the Russian border.

Two Russo-Swedish wars in twenty-five years served as reminders to the Finnish people of how precarious their position between Sweden and Russia was. An increasingly vocal elite in Finland soon determined that Finnish ties with Sweden were becoming too costly, and following Gustav III's War (1788–1790), the Finnish elite's desire to break with Sweden only heightened.[32]

In the late eighteenth century a politically active portion of the Finnish nobility became convinced that, due to Sweden and Russia's repeated use of Finland as a battlefield, it would be in the country's best interests to seek autonomy. Even before the Russo-Swedish War of 1788–1790, there were conspiring Finns, among them Col G. M. Sprengtporten, who had supported Gustav III's coup in 1772. Sprengporten fell out with the king and resigned his commission in 1777. In the following decade he tried to secure Russian support for an autonomous Finland, and later became an adviser to Catherine II.[32]

Notwithstanding the efforts of Finland's elite and nobility to break ties with Sweden, there was no genuine independence movement in Finland until the early twentieth century. As a matter of fact, at this time the Finnish peasantry was outraged by the actions of their elite and almost exclusively supported Gustav's actions against the conspirators. (The High Court of Turku condemned Sprengtporten as a traitor c. 1793.)[32]

Russian Empire era

On 29 March 1809, having been taken over by the armies of Alexander I of Russia in the Finnish War, Finland became an autonomous Grand Duchy in the Russian Empire until the end of 1917. In 1811, Alexander I incorporated Russian Vyborg province into the Grand Duchy of Finland. During the Russian era, the Finnish language began to gain recognition. From the 1860s onwards, a strong Finnish nationalist movement known as the Fennoman movement grew. Milestones included the publication of what would become Finland's national epic – the Kalevala – in 1835, and the Finnish language's achieving equal legal status with Swedish in 1892.

The Finnish famine of 1866–1868 killed 15% of the population, making it one of the worst famines in European history. The famine led the Russian Empire to ease financial regulations, and investment rose in following decades. Economic and political development was rapid.[34] The GDP per capita was still half of that of the United States and a third of that of Britain.[34]

In 1906, universal suffrage was adopted in the Grand Duchy of Finland. However, the relationship between the Grand Duchy and the Russian Empire soured when the Russian government made moves to restrict Finnish autonomy. For example, the universal suffrage was, in practice, virtually meaningless, since the tsar did not have to approve any of the laws adopted by the Finnish parliament. Desire for independence gained ground, first among radical liberals[35] and socialists.

Civil war and early independence

After the 1917 February Revolution, the position of Finland as part of the Russian Empire was questioned, mainly by Social Democrats. Since the head of state was the tsar of Russia, it was not clear who the chief executive of Finland was after the revolution. The parliament, controlled by social democrats, passed the so-called Power Act to give the highest authority to parliament. This was rejected by the Russian Provisional Government which dissolved the parliament.[36]

New elections were conducted, in which right-wing parties won a slim majority. Some social democrats refused to accept the result and still claimed that the dissolution of the parliament (and thus the ensuing elections) were extralegal. The two nearly equally powerful political blocs, the right-wing parties and the social democratic party, were highly antagonized.

The October Revolution in Russia changed the game anew. Suddenly, the right-wing parties in Finland started to reconsider their decision to block the transfer of highest executive power from the Russian government to Finland, as the Bolsheviks took power in Russia. Rather than acknowledge the authority of the Power Law of a few months earlier, the right-wing government declared independence on 6 December 1917.

On 27 January 1918, the official opening shots of the war were fired in two simultaneous events. The government started to disarm the Russian forces in Pohjanmaa, and the Social Democratic Party staged a coup. The latter succeeded in controlling southern Finland and Helsinki, but the white government continued in exile from Vaasa. This sparked the brief but bitter civil war. The Whites, who were supported by Imperial Germany, prevailed over the Reds.[37] After the war, tens of thousands of Reds and suspected sympathizers were interned in camps, where thousands died by execution or from malnutrition and disease. Deep social and political enmity was sown between the Reds and Whites and would last until the Winter War and beyond. The civil war and activist expeditions into Soviet Russia strained Eastern relations.

After a brief flirtation with monarchy, Finland became a presidential republic, with Kaarlo Juho Ståhlberg elected as its first president in 1919. The Finnish–Russian border was determined by the Treaty of Tartu in 1920, largely following the historic border but granting Pechenga (Finnish: Petsamo) and its Barents Sea harbour to Finland. Finnish democracy did not see any Soviet coup attempts and survived the anti-Communist Lapua Movement. The relationship between Finland and the Soviet Union was tense. Germany's relations with democratic Finland cooled also after the Nazis' rise to power. Army officers were trained in France, and relations to Western Europe and Sweden were strengthened.

In 1917, the population was 3 million. Credit-based land reform was enacted after the civil war, increasing the proportion of capital-owning population.[34] About 70% of workers were occupied in agriculture and 10% in industry.[38] The largest export markets were the United Kingdom and Germany.

World War II

During World War II, Finland fought the Soviet Union twice: in the Winter War of 1939–1940 after the Soviet Union had attacked Finland; and in the Continuation War of 1941–1944, following Operation Barbarossa, during which Finland aligned, however not allied, with Germany following its invasion of the Soviet Union. After fighting a major Soviet offensive in June/July 1944 to a standstill, Finland reached an armistice with the Soviet Union. This was followed by the Lapland War of 1944–1945, when Finland fought against the retreating German forces in northern Finland.

The treaties signed in 1947 and 1948 with the Soviet Union included Finnish obligations, restraints, and reparations—as well as further Finnish territorial concessions in addition to those in the Moscow Peace Treaty of 1940. As a result of the two wars, Finland was forced to cede most of Finnish Karelia, Salla, and Petsamo, which amounted to 10% of its land area and 20% of its industrial capacity, including the ports of Vyborg (Viipuri) and the ice-free Liinakhamari (Liinahamari). Almost the whole population, some 400,000 people, fled these areas. Finland was never occupied by Soviet forces; it retained its independence, however, at a loss of about 93,000 soldiers.

Finland rejected Marshall aid, in apparent deference to Soviet desires. However, the United States provided secret development aid and helped the (non-Communist) Social Democratic Party in hopes of preserving Finland's independence.[39] Establishing trade with the Western powers, such as the United Kingdom, and the reparations to the Soviet Union caused Finland to transform itself from a primarily agrarian economy to an industrialised one. For example, the Valmet corporation was founded to create materials for war reparations. Even after the reparations had been paid off, Finland—which was poor in certain resources necessary for an industrialized nation (such as iron and oil)—continued to trade with the Soviet Union in the framework of bilateral trade.

Cold War

In 1950, 46% of Finnish workers worked in agriculture and a third lived in urban areas.[40] The new jobs in manufacturing, services, and trade quickly attracted people to the towns. The average number of births per woman declined from a baby boom peak of 3.5 in 1947 to 1.5 in 1973.[40] When baby-boomers entered the workforce, the economy did not generate jobs fast enough, and hundreds of thousands emigrated to the more industrialized Sweden, with emigration peaking in 1969 and 1970.[40] The 1952 Summer Olympics brought international visitors. Finland took part in trade liberalization in the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade.

Officially claiming to be neutral, Finland lay in the grey zone between the Western countries and the Soviet Union. The YYA Treaty (Finno-Soviet Pact of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance) gave the Soviet Union some leverage in Finnish domestic politics. This was extensively exploited by president Urho Kekkonen against his opponents. He maintained an effective monopoly on Soviet relations from 1956 on, which was crucial for his continued popularity. In politics, there was a tendency of avoiding any policies and statements that could be interpreted as anti-Soviet. This phenomenon was given the name "Finlandization" by the German press.

Despite close relations with the Soviet Union, Finland remained a Western European market economy. Various industries benefited from trade privileges with the Soviets, which explains the widespread support that pro-Soviet policies enjoyed among business interests in Finland. Economic growth was rapid in the postwar era, and by 1975 Finland's GDP per capita was the 15th highest in the world. In the 1970s and 80s, Finland built one of the most extensive welfare states in the world. Finland negotiated with the EEC (a predecessor of the European Union) a treaty that mostly abolished customs duties towards the EEC starting from 1977, although Finland did not fully join. In 1981, president Urho Kekkonen's failing health forced him to retire after holding office for 25 years.

Finland reacted cautiously to the collapse of the Soviet Union, but swiftly began increasing integration with the West. On 21 September 1990, Finland declared unilaterally the Paris Peace Treaty obsolete, following the German reunification decision nine days earlier.[41]

Recent history

.jpg)

Miscalculated macroeconomic decisions, a banking crisis, the collapse of its largest single trading partner (the Soviet Union), and a global economic downturn caused a deep early 1990s recession in Finland. The depression bottomed out in 1993, and Finland saw steady economic growth for more than ten years. Like other Nordic countries, Finland decentralised its economy since the late 1980s. Financial and product market regulation were loosened. Some state enterprises have been privatized and there have been some modest tax cuts. Finland joined the European Union in 1995, and the Eurozone in 1999. Much of the late 1990s economic growth was fueled by the phenomenal success of the mobile phone manufacturer Nokia, which held a unique position of representing 80% of the market capitalization of the Helsinki Stock Exchange.

The population is aging with the birth rate at 10.42 births per 1,000 population per year, or a fertility rate of 1.8.[40] With a median age of 42.7 years, Finland is one of countries with most mature population;[42] half of voters are estimated to be over 50 years old.

Geography

Lying approximately between latitudes 60° and 70° N, and longitudes 20° and 32° E, Finland is one of the world's northernmost countries. Of world capitals, only Reykjavík lies more to the north than Helsinki. The distance from the southernmost—Hanko—to the northernmost point in the country—Nuorgam—is 1,160 kilometres (720 mi).

Finland is a country of thousands of lakes and islands—about 188,000 lakes (larger than 500 m2 or 0.12 acres) and 179,000 islands.[43] Its largest lake, Saimaa, is the fourth largest in Europe. The area with the most lakes is called Finnish Lakeland. The greatest concentration of islands is found in the southwest in the Archipelago Sea between continental Finland and the main island of Åland.

Much of the geography of Finland is explained by the Ice Age. The glaciers were thicker and lasted longer in Fennoscandia compared with the rest of Europe. Their eroding effects have left the Finnish landscape mostly flat with few hills and fewer mountains. Its highest point, the Halti at 1,324 metres (4,344 ft), is found in the extreme north of Lapland at the border between Finland and Norway. The highest mountain whose peak is entirely in Finland is Ridnitsohkka at 1,316 m (4,318 ft), directly adjacent to Halti.

The retreating glaciers have left the land with morainic deposits in formations of eskers. These are ridges of stratified gravel and sand, running northwest to southeast, where the ancient edge of the glacier once lay. Among the biggest of these are the three Salpausselkä ridges that run across southern Finland.

Having been compressed under the enormous weight of the glaciers, terrain in Finland is rising due to the post-glacial rebound. The effect is strongest around the Gulf of Bothnia, where land steadily rises about 1 cm (0.4 in) a year. As a result, the old sea bottom turns little by little into dry land: the surface area of the country is expanding by about 7 square kilometres (2.7 sq mi) annually.[44] Relatively speaking, Finland is rising from the sea.[45]

The landscape is covered mostly by coniferous taiga forests and fens, with little cultivated land. Of the total area 10% is lakes, rivers and ponds, and 78% forest. The forest consists of pine, spruce, birch, and other species.[46] Finland is the largest producer of wood in Europe and among the largest in the world. The most common type of rock is granite. It is a ubiquitous part of the scenery, visible wherever there is no soil cover. Moraine or till is the most common type of soil, covered by a thin layer of humus of biological origin. Podzol profile development is seen in most forest soils except where drainage is poor. Gleysols and peat bogs occupy poorly drained areas.

Biodiversity

Phytogeographically, Finland is shared between the Arctic, central European, and northern European provinces of the Circumboreal Region within the Boreal Kingdom. According to the WWF, the territory of Finland can be subdivided into three ecoregions: the Scandinavian and Russian taiga, Sarmatic mixed forests, and Scandinavian Montane Birch forest and grasslands. Taiga covers most of Finland from northern regions of southern provinces to the north of Lapland. On the southwestern coast, south of the Helsinki-Rauma line, forests are characterized by mixed forests, that are more typical in the Baltic region. In the extreme north of Finland, near the tree line and Arctic Ocean, Montane Birch forests are common.

Similarly, Finland has a diverse and extensive range of fauna. There are at least sixty native mammalian species, 248 breeding bird species, over 70 fish species, and 11 reptile and frog species present today, many migrating from neighboring countries thousands of years ago. Large and widely recognized wildlife mammals found in Finland are the brown bear (the national animal), gray wolf, wolverine, and elk. Three of the more striking birds are the whooper swan, a large European swan and the national bird of Finland; the capercaillie, a large, black-plumaged member of the grouse family; and the European eagle-owl. The latter is considered an indicator of old-growth forest connectivity, and has been declining because of landscape fragmentation.[47] The most common breeding birds are the willow warbler, common chaffinch, and redwing.[48] Of some seventy species of freshwater fish, the northern pike, perch, and others are plentiful. Atlantic salmon remains the favourite of fly rod enthusiasts.

The endangered Saimaa ringed seal, one of only three lake seal species in the world, exists only in the Saimaa lake system of southeastern Finland, down to only 300 seals today. It has become the emblem of the Finnish Association for Nature Conservation.[49]

Climate

The main factor influencing Finland's climate is the country's geographical position between the 60th and 70th northern parallels in the Eurasian continent's coastal zone. In the Köppen climate classification, the whole of Finland lies in the boreal zone, characterized by warm summers and freezing winters. Within the country, the temperateness varies considerably between the southern coastal regions and the extreme north, showing characteristics of both a maritime and a continental climate. Finland is near enough to the Atlantic Ocean to be continuously warmed by the Gulf Stream. The Gulf Stream combines with the moderating effects of the Baltic Sea and numerous inland lakes to explain the unusually warm climate compared with other regions that share the same latitude, such as Alaska, Siberia, and southern Greenland.[50]

Winters in southern Finland (when mean daily temperature remains below 0 °C or 32 °F) are usually about 100 days long, and in the inland the snow typically covers the land from about late November to April, and on the coastal areas such as Helsinki, snow often covers the land from late December to late March.[51] Even in the south, the harshest winter nights can see the temperatures fall to −30 °C (−22 °F) although on coastal areas like Helsinki, temperatures below −30 °C (−22 °F) are very rare. Climatic summers (when mean daily temperature remains above 10 °C or 50 °F) in southern Finland last from about late May to mid-September, and in the inland, the warmest days of July can reach over 35 °C (95 °F).[50] Although most of Finland lies on the taiga belt, the southernmost coastal regions are sometimes classified as hemiboreal.[52]

In northern Finland, particularly in Lapland, the winters are long and cold, while the summers are relatively warm but short. The most severe winter days in Lapland can see the temperature fall down to −45 °C (−49 °F). The winter of the north lasts for about 200 days with permanent snow cover from about mid-October to early May. Summers in the north are quite short, only two to three months, but can still see maximum daily temperatures above 25 °C (77 °F) during heat waves.[50] No part of Finland has Arctic tundra, but Alpine tundra can be found at the fells Lapland.[52]

The Finnish climate is suitable for cereal farming only in the southernmost regions, while the northern regions are suitable for animal husbandry.[53]

A quarter of Finland's territory lies within the Arctic Circle and the midnight sun can be experienced for more days the farther north one travels. At Finland's northernmost point, the sun does not set for 73 consecutive days during summer, and does not rise at all for 51 days during winter.[50]

Regions

Finland consists of 19 regions called maakunta in Finnish and landskap in Swedish. The regions are governed by regional councils which serve as forums of cooperation for the municipalities of a region. The main tasks of the regions are regional planning and development of enterprise and education. In addition, the public health services are usually organized on the basis of regions. Currently, the only region where a popular election is held for the council is Kainuu. Other regional councils are elected by municipal councils, each municipality sending representatives in proportion to its population.

In addition to inter-municipal cooperation, which is the responsibility of regional councils, each region has a state Employment and Economic Development Centre which is responsible for the local administration of labour, agriculture, fisheries, forestry, and entrepreneurial affairs. The Finnish Defence Forces regional offices are responsible for the regional defence preparations and for the administration of conscription within the region.

Regions represent dialectal, cultural, and economic variations better than the former provinces, which were purely administrative divisions of the central government. Historically, regions are divisions of historical provinces of Finland, areas which represent dialects and culture more accurately.

Six Regional State Administrative Agencies were created by the state of Finland in 2010, each of them responsible for one of the regions called alue in Finnish and region in Swedish; in addition, Åland was designated a seventh region. These take over some of the tasks of the earlier Provinces of Finland (the läänis), which were abolished.[54]

The region of Eastern Uusimaa was consolidated with Uusimaa on 1 January 2011.[56]

Administrative divisions

The fundamental administrative divisions of the country are the municipalities, which may also call themselves towns or cities. They account for half of public spending. Spending is financed by municipal income tax, state subsidies, and other revenue. As of 2015, there are 317 municipalities,[9] and most have fewer than 6,000 residents.

In addition to municipalities, two intermediate levels are defined. Municipalities co-operate in seventy sub-regions and nineteen regions. These are governed by the member municipalities and have only limited powers. The autonomous province of Åland has a permanent democratically elected regional council. In the Kainuu region, there is a pilot project underway with regional elections. Sami people have a semi-autonomous Sami Domicile Area in Lapland for issues on language and culture.

In the following chart, the number of inhabitants includes those living in the entire municipality (kunta/kommun), not just in the built-up area. The land area is given in km², and the density in inhabitants per km² (land area). The figures are as of 31 March 2016. The capital region – comprising Helsinki, Vantaa, Espoo and Kauniainen – forms a continuous conurbation of over 1.1 million people. However, common administration is limited to voluntary cooperation of all municipalities, e.g. in Helsinki Metropolitan Area Council.

| City | Population[57] | Land area[58] | Density | Regional Map | Population Map |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Helsinki | 629,512 | 213.75 | 2,945.09 |

Municipalities (thin borders) and regions (thick borders) of Finland (2009). |

Population map of Finland |

| Espoo | 270,416 | 312.26 | 866 | ||

| Tampere | 225,485 | 525.03 | 429.47 | ||

| Vantaa | 215,813 | 238.37 | 905.37 | ||

| Oulu | 198,804 | 1,410.17 | 140.98 | ||

| Turku | 186,030 | 245.67 | 757.24 | ||

| Jyväskylä | 137,392 | 1,170.99 | 117.33 | ||

| Kuopio | 112,158 | 1,597.39 | 70.21 | ||

| Lahti | 118,885 | 135.05 | 880.3 | ||

| Kouvola | 85,808 | 2,558.24 | 33.54 | ||

| Pori | 85,256 | 834.06 | 102.22 | ||

| Joensuu | 75,557 | 2,381.76 | 31.72 | ||

| Lappeenranta | 72,868 | 1,433.36 | 50.84 | ||

| Hämeenlinna | 67,914 | 1,785.76 | 38.03 | ||

| Vaasa | 67,495 | 188.81 | 357.48 |

Politics

Constitution

The Constitution of Finland defines the political system. Finland is a parliamentary democracy, and the prime minister is the country's most powerful politician. The constitution in its current form came into force on 1 March 2000, and was amended on 1 March 2012. Citizens can run and vote in parliamentary, municipal, and presidential elections, and in European Union elections.

President

The head of state of Finland is president of the Republic of Finland (in Finnish Suomen tasavallan presidentti, in Swedish republiken Finlands president). Finland has for most of its independence had a semipresidential system, but in last decades the powers of the President of Finland have been diminished. In constitution amendments, which came into effect in 1991 or 1992, 2000 and 2012, the President's position has become primarily ceremonary. However, the President still leads the nation's foreign politics together with the Council of state and is the chief-in-command of the Defence Forces.[1] The position still does entail some powers, including responsibility for foreign policy (excluding affairs related to the European Union) in cooperation with the cabinet, being the head of the armed forces, some decree powers, and some appointive powers. Direct, one- or two-stage elections are used to elect the president for a term of six years and for a maximum of two consecutive terms. The current president is Sauli Niinistö; he took office on 1 March 2012. The former presidents were K. J. Ståhlberg (1919–1925), L. K. Relander (1925–1931), P. E. Svinhufvud (1931–1937), Kyösti Kallio (1937–1940), Risto Ryti (1940–1944), C. G. E. Mannerheim (1944–1946), J. K. Paasikivi (1946–1956), Urho Kekkonen (1956–1982), Mauno Koivisto (1982–1994), Martti Ahtisaari (1994–2000), and Tarja Halonen (2000–2012).

The current president was elected from the ranks of the National Coalition Party, first time since 1946. Until that the presidency was held by socialists or agrarian party.

Parliament

The 200-member unicameral Parliament of Finland called Eduskunta exercises supreme legislative authority. It may alter the constitution and ordinary laws, dismiss the cabinet, and override presidential vetoes. Its acts are not subject to judicial review; the constitutionality of new laws is assessed by the parliament's constitutional law committee. The parliament is elected for a term of four years using the proportional D'Hondt method within a number of multi-seat constituencies through open list multi-member districts. Various parliament committees listen to experts and prepare legislation. The speaker is currently Maria Lohela (Finns Party).[59]

Since universal suffrage was introduced in 1906, the parliament has been dominated by the Centre Party (former Agrarian Union), the National Coalition Party (conservatives), and the Social Democrats. These parties have enjoyed approximately equal support, and their combined vote has totalled about 65–80% of all votes. Their lowest common total of MPs, 121, was reached in the 2011 elections. For a few decades after 1944, the Communists were a strong fourth party. Due to the electoral system of proportional representation, and the relative reluctance of voters to switch their support between parties, the relative strengths of the parties have commonly varied only slightly from one election to another. However, there have been some long-term trends, such as the rise and fall of the Communists during the Cold War; the steady decline into insignificance of the Liberal party and its predecessors from 1906 to about 1980; and the rise of the Green party and its predecessor since 1983. In the 2011 elections, the True Finns achieved exceptional success, increasing its representation from 5 to 39 seats, and thus surpassing the Centre Party.[60]

The autonomous province of Åland, which forms a federacy with Finland, elects one member to the parliament, who traditionally joins the parliamentary group of the Swedish People's Party of Finland. (The province also holds elections for its own permanent regional council, and in the 2011 elections, Åland Centre was the largest party.)

|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Finland |

|

Legislative

|

|

|

The Parliament can be dissolved by a recommendation of the Prime minister endorsed by the President. This procedure has never been used, although the parliament was dissolved several times under the pre-2000 constitution, when this action was the sole prerogative of the president.

After the parliamentary elections on 19 April 2015, the seats were divided among eight parties as follows:[61]

| Party | Seats | Net gain/loss | % of seats | % of votes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Centre Party | 49 | +14 | 24.5 | 21.1 |

| Finns Party | 38 | −1 | 19.0 | 17.7 |

| National Coalition Party | 37 | −7 | 18.5 | 18.2 |

| Social Democratic Party | 34 | −8 | 17.0 | 16.5 |

| Green League | 15 | +5 | 7.5 | 8.5 |

| Left Alliance | 12 | −2 | 6.0 | 7.1 |

| Swedish People's Party | 9 | 0 | 4.5 | 4.9 |

| Christian Democrats | 5 | −1 | 2.5 | 3.5 |

| Others | 1a | 0 | 0.5 | 0.6 |

| a Province of Åland's representative. | ||||

Cabinet

After parliamentary elections, the parties negotiate among themselves on forming a new cabinet (the Finnish Government), which then has to be approved by a simple majority vote in the parliament. The cabinet can be dismissed by a parliamentary vote of no confidence, although this rarely happens (the last time in 1957), as the parties represented in the cabinet usually make up a majority in the parliament.[62]

The cabinet exercises most executive powers, and originates most of the bills that the parliament then debates and votes on. It is headed by the Prime Minister of Finland, and consists of him or her, of other ministers, and of the Chancellor of Justice. The current prime minister is Juha Sipilä (Centre Party). Each minister heads his or her ministry, or, in some cases, has responsibility for a subset of a ministry's policy. After the prime minister, the most powerful minister is the minister of finance, the incumbent Minister of Finance is Petteri Orpo.

As no one party ever dominates the parliament, Finnish cabinets are multi-party coalitions. As a rule, the post of prime minister goes to the leader of the biggest party and that of the minister of finance to the leader of the second biggest.

Law

The judicial system of Finland is a civil law system divided between courts with regular civil and criminal jurisdiction and administrative courts with jurisdiction over litigation between individuals and the public administration. Finnish law is codified and based on Swedish law and in a wider sense, civil law or Roman law. The court system for civil and criminal jurisdiction consists of local courts (käräjäoikeus, tingsrätt), regional appellate courts (hovioikeus, hovrätt), and the Supreme Court (korkein oikeus, högsta domstolen). The administrative branch of justice consists of administrative courts (hallinto-oikeus, förvaltningsdomstol) and the Supreme Administrative Court (korkein hallinto-oikeus, högsta förvaltningsdomstolen). In addition to the regular courts, there are a few special courts in certain branches of administration. There is also a High Court of Impeachment for criminal charges against certain high-ranking officeholders.

Around 92% of residents have confidence in Finland's security institutions.[63] The overall crime rate of Finland is not high in the EU context. Some crime types are above average, notably the highest homicide rate in Western Europe.[64] A day fine system is in effect and also applied to offenses such as speeding.

Finland has successfully fought against government corruption, which was more common in the 1970s and 80s.[65] For instance, economic reforms and EU membership introduced stricter requirements for open bidding and many public monopolies were abolished.[65] Today, Finland has a very low number of corruption charges; Transparency International ranks Finland as one of the least corrupt countries in Europe.

In 2008, Transparency International criticized the lack of transparency of the system of Finnish political finance.[66] According to GRECO in 2007, corruption should be taken into account in the Finnish system of election funds better.[67] A scandal revolving around campaign finance of the 2007 parliamentary elections broke out in spring 2008. Nine Ministers of Government submitted incomplete funding reports and even more of the members of parliament. The law includes no punishment of false funds reports of the elected politicians.

Foreign relations

According to the 2012 constitution, the president (currently Sauli Niinistö) leads foreign policy in cooperation with the government, except that the president has no role in EU affairs.[68]

In 2008, president Martti Ahtisaari was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.[69] Finland was considered a cooperative model state, and Finland did not oppose proposals for a common EU defence policy.[70] This was reversed in the 2000s, when Tarja Halonen and Erkki Tuomioja made Finland's official policy to resist other EU members' plans for common defence.[70]

Social security

Finland has one of the world's most extensive welfare systems, one that guarantees decent living conditions for all residents, Finns, and non-citizens. Since the 1980s the social security has been cut back, but still the system is one of the most comprehensive in the world. Created almost entirely during the first three decades after World War II, the social security system was an outgrowth of the traditional Nordic belief that the state was not inherently hostile to the well-being of its citizens, but could intervene benevolently on their behalf. According to some social historians, the basis of this belief was a relatively benign history that had allowed the gradual emergence of a free and independent peasantry in the Nordic countries and had curtailed the dominance of the nobility and the subsequent formation of a powerful right wing. Finland's history has been harsher than the histories of the other Nordic countries, but not harsh enough to bar the country from following their path of social development.[71]

Military

The Finnish Defence Forces consist of a cadre of professional soldiers (mainly officers and technical personnel), currently serving conscripts, and a large reserve. The standard readiness strength is 34,700 people in uniform, of which 25% are professional soldiers. A universal male conscription is in place, under which all male Finnish nationals above 18 years of age serve for 6 to 12 months of armed service or 12 months of civilian (non-armed) service. Voluntary post-conscription overseas peacekeeping service is popular, and troops serve around the world in UN, NATO, and EU missions. Approximately 500 women choose voluntary military service every year.[72] Women are allowed to serve in all combat arms including front-line infantry and special forces. The army consists of a highly mobile field army backed up by local defence units. The army defends the national territory and its military strategy employs the use of the heavily forested terrain and numerous lakes to wear down an aggressor, instead of attempting to hold the attacking army on the frontier.

Finnish defence expenditure per capita is one of the highest in the European Union.[73] The Finnish military doctrine is based on the concept of total defence. The term total means that all sectors of the government and economy are involved in the defence planning. The armed forces are under the command of the Chief of Defence (currently General Jarmo Lindberg), who is directly subordinate to the president in matters related to military command. The branches of the military are the army, the navy, and the air force. The border guard is under the Ministry of the Interior but can be incorporated into the Defence Forces when required for defence readiness.

Even while Finland hasn't joined the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, the country has joined the NATO Response Force, the EU Battlegroup, the NATO Partnership for Peace and in signed a NATO Memorandum of Understanding,[74] thus forming a practical coalition.[12] In 2015, the Finland-NATO ties were strengthened with a host nation support agreement allowing assistance from NATO troops in emergency situations.[75] Finland has been active participant in the Afghanistan and Kosovo.[76][77] Recently Finland has been more eager to discuss about its current and planned roles in Syria, Iraq and war against ISIL.[78] On 21 December 2012 Finnish military officer Atte Kaleva was reported to have been kidnapped and later released in Yemen for ransom. At first he was reported be a casual Arabic student, however only later it was published that his studies were about jihadists, terrorism, and that he was employed by the military.[79][80] As response to French request for solidarity, Finnish defence minister commented in November that Finland could and is willing to offer intelligence support.[81]

In May 2015, Finnish Military sent nearly one million letters to all relevant males in the country, informing them about their roles in the war effort. It was globally speculated that Finland was preparing for war—however Finland claimed that this was a standard procedure, yet something never done before in Finnish history.[82] Mr Hypponen however said that this is not an isolated case, but bound to the European security dilemma.[82] The NATO Memorandum of Understanding signed earlier bestows an obligation e.g. to report on internal capabilities and the availability thereof to NATO.[74]

Economy

The economy of Finland has a per capita output equal to that of other European economies such as France, Germany, Belgium, or the UK. The largest sector of the economy is services at 66%, followed by manufacturing and refining at 31%. Primary production is 2.9%.[83] With respect to foreign trade, the key economic sector is manufacturing. The largest industries in 2007[84] were electronics (22%); machinery, vehicles, and other engineered metal products (21.1%); forest industry (13%); and chemicals (11%). The gross domestic product peaked in 2008. As of 2015, the country's economy is at 2006 level.[85][86]

Finland has significant timber, mineral (iron, chromium, copper, nickel, and gold) and freshwater resources. Forestry, paper factories, and the agricultural sector (on which taxpayers spend around 3 billion euros annually) are politically sensitive to rural residents. The Greater Helsinki area generates around a third of GDP. In a 2004 OECD comparison, high-technology manufacturing in Finland ranked second largest after Ireland. Knowledge-intensive services have also ranked the smallest and slow-growth sectors – especially agriculture and low-technology manufacturing – second largest after Ireland.[87] Overall short-term outlook was good and GDP growth has been above many EU peers.

Finland is highly integrated into the global economy, and international trade is a third of GDP. The European Union makes up 60% of the total trade. The largest trade flows are with Germany, Russia, Sweden, United Kingdom, United States, Netherlands, and China. Trade policy is managed by the European Union, where Finland has traditionally been among the free trade supporters, except for agriculture. Finland is the only Nordic country to have joined the Eurozone.

Finland's climate and soils make growing crops a particular challenge. The country lies between latitudes 60°N and 70°N, and has severe winters and relatively short growing seasons that are sometimes interrupted by frosts. However, because the Gulf Stream and the North Atlantic Drift Current moderate the climate, Finland contains half of the world's arable land north of 60° north latitude. Annual precipitation is usually sufficient, but it occurs almost exclusively during the winter months, making summer droughts a constant threat. In response to the climate, farmers have relied on quick-ripening and frost-resistant varieties of crops, and they have cultivated south-facing slopes as well as richer bottomlands to ensure production even in years with summer frosts. Most farmland had originally been either forest or swamp, and the soil had usually required treatment with lime and years of cultivation to neutralize excess acid and to develop fertility. Irrigation was generally not necessary, but drainage systems were often needed to remove excess water. Finland's agriculture was efficient and productive—at least when compared with farming in other European countries.[71]

Forests play a key role in the country's economy, making it one of the world's leading wood producers and providing raw materials at competitive prices for the crucial wood-processing industries. As in agriculture, the government has long played a leading role in forestry, regulating tree cutting, sponsoring technical improvements, and establishing long-term plans to ensure that the country's forests continue to supply the wood-processing industries. To maintain the country's comparative advantage in forest products, Finnish authorities moved to raise lumber output toward the country's ecological limits. In 1984, the government published the Forest 2000 plan, drawn up by the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry. The plan aimed at increasing forest harvests by about 3% per year, while conserving forestland for recreation and other uses.[71]

Private sector employees amount to 1.8 million, out of which around a third with tertiary education. The average cost of a private sector employee per hour was 25.1 euros in 2004.[88] As of 2008, average purchasing power-adjusted income levels are similar to those of Italy, Sweden, Germany, and France.[89] In 2006, 62% of the workforce worked for enterprises with less than 250 employees and they accounted for 49% of total business turnover and had the strongest rate of growth.[90] The female employment rate is high. Gender segregation between male-dominated professions and female-dominated professions is higher than in the US.[91] The proportion of part-time workers was one of the lowest in OECD in 1999.[91] In 2013, the 10 largest private sector employers in Finland were Itella, Nokia, OP-Pohjola, ISS, VR, Kesko, UPM-Kymmene, YIT, Metso, and Nordea.[92]

The unemployment rate was 9.4% in 2015, having risen from 8.7% in 2014.[93] Youth unemployment rate rose from 16.5% in 2007 to 20.5% in 2014.[94] A fifth of residents are outside the job market at the age of 50 and less than a third are working at the age of 61.[95] As of today, nearly one million people are living with minimal wages or unemployed not enough to cover their costs of living.[96]

As of 2006, 2.4 million households reside in Finland. The average size is 2.1 persons; 40% of households consist of a single person, 32% two persons and 28% three or more persons. Residential buildings total 1.2 million, and the average residential space is 38 square metres (410 sq ft) per person. The average residential property without land costs 1,187 euro per sq metre and residential land 8.6 euro per sq metre. 74% of households had a car. There are 2.5 million cars and 0.4 million other vehicles.[97]

Around 92% have a mobile phone and 83.5% (2009) Internet connection at home. The average total household consumption was 20,000 euro, out of which housing consisted of about 5,500 euro, transport about 3,000 euro, food and beverages excluding alcoholic beverages at around 2,500 euro, and recreation and culture at around 2,000 euro.[98] According to Invest in Finland, private consumption grew by 3% in 2006 and consumer trends included durables, high quality products, and spending on well-being.[99]

Energy

Anyone can enter the free and largely privately owned financial and physical Nordic energy markets traded in NASDAQ OMX Commodities Europe and Nord Pool Spot exchanges, which have provided competitive prices compared with other EU countries. As of 2007, Finland has roughly the lowest industrial electricity prices in the EU-15 (equal to France).[101]

In 2006, the energy market was around 90 terawatt hours and the peak demand around 15 gigawatts in winter. This means that the energy consumption per capita is around 7.2 tons of oil equivalent per year. Industry and construction consumed 51% of total consumption, a relatively high figure reflecting Finland's industries.[102][103] Finland's hydrocarbon resources are limited to peat and wood. About 10–15% of the electricity is produced by hydropower,[104] which is low compared with more mountainous Sweden or Norway. In 2008, renewable energy (mainly hydropower and various forms of wood energy) was high at 31% compared with the EU average of 10.3% in final energy consumption.[105]

Finland has four privately owned nuclear reactors producing 18% of the country's energy[107] and one research reactor at the Otaniemi campus. The fifth AREVA-Siemens-built reactor—the world's largest at 1600 MWe and a focal point of Europe's nuclear industry—has faced many delays and is currently scheduled to be operational by 2018–2020, a decade after the original planned opening.[108] A varying amount (5–17%) of electricity has been imported from Russia (at around 3 gigawatt power line capacity), Sweden and Norway.

Energy companies are about to increase nuclear power production, as in July 2010 the Finnish parliament granted permits for additional two new reactors.

Transport

The extensive road system is utilized by most internal cargo and passenger traffic. The annual state operated road network expenditure of around 1 billion euro is paid with vehicle and fuel taxes which amount to around 1.5 billion euro and 1 billion euro.

The main international passenger gateway is Helsinki Airport with about 16 million passengers in 2014. Oulu Airport is the second largest, whilst another 25 airports have scheduled passenger services.[109] The Helsinki Airport-based Finnair, Blue1, and Nordic Regional Airlines sell air services both domestically and internationally. Helsinki has an optimal location for great circle (i.e. the shortest and most efficient) routes between Western Europe and the Far East.

Despite low population density, the Government spends annually around 350 million euro in maintaining 5,865 kilometres (3,644 mi) of railway tracks. Rail transport is handled by state owned VR Group, which has 5% passenger market share (out of which 80% are urban trips in Greater Helsinki) and 25% cargo market share.[110] Since 12 December 2010, Karelian Trains, a joint venture between Russian Railways and VR (Finnish Railways), has been running Alstom Pendolino operated high-speed services between Saint Petersburg's Finlyandsky and Helsinki's Central railway stations. These services are branded as "Allegro" trains. The journey from Helsinki to Saint Petersburg takes only three and a half hours.

The majority of international cargo utilizes ports. Port logistics prices are low. Vuosaari Harbour in Helsinki is the largest container port after completion in 2008 and others include Kotka, Hamina, Hanko, Pori, Rauma, and Oulu. There is passenger traffic from Helsinki and Turku, which have ferry connections to Tallinn, Mariehamn, and Stockholm. The Helsinki-Tallinn route, one of the busiest passenger sea routes in the world, has also been served by a helicopter line.

Industry

Finland was rapidly industrialized after the Second World War, achieving GDP per capita levels equal to that of Japan or the UK in the beginning of the 1970s. Initially, most development was based on two broad groups of export-led industries, the "metal industry" (metalliteollisuus) and "forest industry" (metsäteollisuus). The "metal industry" includes shipbuilding, metalworking, the car industry, engineered products such as motors and electronics, and production of metals (steel, copper and chromium). The world's biggest cruise ships are built in Finnish shipyards. The "forest industry" (metsäteollisuus) includes forestry, timber, pulp and paper, and is a logical development based on Finland's extensive forest resources (77% of the area is covered by forest, most of it in renewable use). In the pulp and paper industry, many of the largest companies are based in Finland (Ahlstrom, M-real, and UPM). However, the Finnish economy has diversified, with expansion into fields such as electronics (e.g. Nokia), metrology (Vaisala), transport fuels (Neste), chemicals (Kemira), engineering consulting (Pöyry), and information technology (e.g. Rovio, known for Angry Birds), and is no longer dominated by the two sectors of metal and forest industry. Likewise, the structure has changed, with the service sector growing, with manufacturing reducing in importance; agriculture is only a minor part. Despite this, production for export is still more prominent than in Western Europe, thus making Finland more vulnerable to global economic trends.

In an Economist Intelligence Unit report released in September 2011, Finland clinched the second place after the United States on Benchmarking IT Industry Competitiveness 2011 which scored on 6 key indicators: overall business environment, technology infrastructure, human capital, legal framework, public support for industry development, and research and development landscape.[111]

Public policy

Finnish politicians have often emulated other Nordics and the Nordic model.[112] Nordics have been free-trading and relatively welcoming to skilled migrants for over a century, though in Finland immigration is relatively new. The level of protection in commodity trade has been low, except for agricultural products.[112]

Finland has top levels of economic freedom in many areas. Finland is ranked 16th in the 2008 global Index of Economic Freedom and 9th in Europe.[113] While the manufacturing sector is thriving, the OECD points out that the service sector would benefit substantially from policy improvements.[114]

The 2007 IMD World Competitiveness Yearbook ranked Finland 17th most competitive.[115] The World Economic Forum 2008 index ranked Finland the 6th most competitive.[116] In both indicators, Finland's performance was next to Germany, and significantly higher than most European countries. In the Business competitiveness index 2007–2008 Finland ranked third in the world.

Economists attribute much growth to reforms in the product markets. According to the OECD, only four EU-15 countries have less regulated product markets (UK, Ireland, Denmark and Sweden) and only one has less regulated financial markets (Denmark). Nordic countries were pioneers in liberalizing energy, postal, and other markets in Europe.[112] The legal system is clear and business bureaucracy less than most countries.[113] Property rights are well protected and contractual agreements are strictly honoured.[113] Finland is rated the least corrupt country in the world in the Corruption Perceptions Index[117] and 13th in the Ease of Doing Business Index. This indicates exceptional ease in cross-border trading (5th), contract enforcement (7th), business closure (5th), tax payment (83rd), and low worker hardship (127th).[118]

Finnish law forces all workers to obey the national contracts that are drafted every few years for each profession and seniority level. The agreement becomes universally enforceable provided that more than 50% of the employees support it, in practice by being a member of a relevant trade union. The unionization rate is high (70%), especially in the middle class (AKAVA—80%). A lack of a national agreement in an industry is considered an exception.[87][112]

Tourism

In 2005, Finnish tourism grossed over €6.7 billion with a 5% increase from the previous year. Much of the sudden growth can be attributed to the globalisation and modernisation of the country as well as a rise in positive publicity and awareness. There are many attractions in Finland which attracted over 8 million visitors in 2013.

The Finnish landscape is covered with thick pine forests and rolling hills, and complemented with a labyrinth of lakes and inlets. Much of Finland is pristine and virgin as it contains 37 national parks from the Southern shores of the Gulf of Finland to the high fells of Lapland. Finland also has urbanised regions with many cultural events and activities.

Commercial cruises between major coastal and port cities in the Baltic region, including Helsinki, Turku, Tallinn, Stockholm, and Travemünde, play a significant role in the local tourism industry. Finland is locally regarded as the home of Saint Nicholas or Santa Claus, living in the northern Lapland region. Above the Arctic Circle, in midwinter, there is a polar night, a period when the sun does not rise for days or weeks, or even months, and correspondingly, midnight sun in the summer, with no sunset even at midnight (for up to 73 consecutive days, at the northernmost point). Lapland is so far north that the Aurora Borealis, fluorescence in the high atmosphere due to solar wind, is seen regularly in the fall, winter, and spring.

Outdoor activities range from Nordic skiing, golf, fishing, yachting, lake cruises, hiking, and kayaking, among many others. Wildlife is abundant in Finland. Bird-watching is popular for those fond of avifauna, however hunting is also popular. Elk and hare are common game in Finland. Olavinlinna in Savonlinna hosts the annual Savonlinna Opera Festival.

Demographics

The population of Finland is currently about 5,500,000.[8] Finland has an average population density of 18 inhabitants per square kilometre. This is the third-lowest population density of any European country, behind those of Norway and Iceland, and the lowest population density in the EU. Finland's population has always been concentrated in the southern parts of the country, a phenomenon that became even more pronounced during 20th-century urbanisation. The largest cities in Finland are those of the Greater Helsinki metropolitan area—Helsinki, Espoo, and Vantaa. Other cities with population over 100,000 are Tampere, Turku, Oulu, Jyväskylä, Kuopio, and Lahti.

As of 2014, there were 322,700 people with a foreign background living in Finland (5.9% of the population), most of whom are from Russia, Estonia, Somalia, Iraq and Yugoslavia.[120] The children of foreigners are not automatically given Finnish citizenship, as Finnish nationality law practices and maintain jus sanguinis policy where only children born to at least one Finnish parent are granted citizenship. If they are born in Finland and cannot get citizenship of any other country, they become citizens.[121] Additionally, certain persons of Finnish descent who reside in countries that were once part of Soviet Union, retain the right of return, a right to establish permanent residency in the country, which would eventually entitle them to qualify for citizenship.[122]

Largest cities

| | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | Region | Pop. | Rank | Name | Region | Pop. | ||

| Helsinki  Tampere |

1 | Helsinki | Uusimaa | 1,159,211 | 11 | Lappeenranta | South Karelia | 54,139 |  Turku  Oulu |

| 2 | Tampere | Pirkanmaa | 313,058 | 12 | Kotka | Kymenlaakso | 52,894 | ||

| 3 | Turku | Finland Proper | 252,468 | 13 | Rovaniemi | Lapland (Finland) | 50,552 | ||

| 4 | Oulu | Northern Ostrobothnia | 200,071 | 14 | Kouvola | Kymenlaakso | 49,787 | ||

| 5 | Jyväskylä | Central Finland | 116,480 | 15 | Hämeenlinna | Tavastia Proper | 49,216 | ||

| 6 | Lahti | Päijänne Tavastia | 115,897 | 16 | Seinäjoki | Southern Ostrobothnia | 45,732 | ||

| 7 | Pori | Satakunta | 84,294 | 17 | Hyvinkää | Uusimaa | 42,278 | ||

| 8 | Kuopio | Northern Savonia | 82,268 | 18 | Porvoo | Uusimaa | 36,861 | ||

| 9 | Vaasa | Ostrobothnia | 64,795 | 19 | Mikkeli | Southern Savonia | 36,009 | ||

| 10 | Joensuu | North Karelia | 63,490 | 20 | Kokkola | Central Ostrobothnia | 35,367 | ||

Languages

Finnish and Swedish are the official languages of Finland. Finnish predominates nationwide while Swedish is spoken in some coastal areas in the west and south and in the autonomous region of Åland. The Sami language is an official language in northern Lapland. Finnish Romani and Finnish Sign Language are also recognized in the constitution. The Nordic languages and Karelian are also specially treated in some contexts.

The native language of 89% of the population is Finnish,[123] which is part of the Finnic subgroup of the Uralic languages. The language is one of only four official EU languages not of Indo-European origin. Finnish is closely related to Karelian and Estonian and more remotely to the Sami languages and Hungarian.

Swedish is the native language of 5% of the population (Swedish-speaking Finns).[123]

To the north, in Lapland, are the Sami people, numbering around 7,000[124] and recognized as an indigenous people. About a quarter of them speak a Sami language as their mother tongue.[125] The Sami languages that are spoken in Finland are Northern Sami, Inari Sami, and Skolt Sami.[note 1] Finnish Romani is spoken by some 5,000–6,000 people. There are two sign languages: Finnish Sign Language, spoken natively by 4,000–5,000 people,[126] and Finland-Swedish Sign Language, spoken natively by about 150 people. Tatar language is spoken by a Finnish Tatar minority of about 800 people who moved to Finland mainly during the Russian rule from the 1870s until the 1920s.[127]

The rights of minority groups (in particular Sami, Swedish speakers, and Romani people) are protected by the constitution.[128]

Immigrant languages include Russian (1.1%), Estonian (0.6%), Somali, English, and Arabic. The largest groups of population of foreign languages in 2012 were Russian, Estonian, and Somali.[129]

The best-known foreign languages are English (63%), German (18%), and French (3%). English is studied by most pupils as a compulsory subject from the third or fifth grade (at 9 or 11 years of age respectively) in the comprehensive school (in some schools other languages can be chosen instead). German, French, and Russian can be studied as second foreign languages from the eighth grade (at 14 years of age; some schools may offer other options). A third foreign language may be studied in upper secondary school or university (at 16 years of age or over).

Norwegian and, to some extent, Danish are mutually intelligible with Swedish and are thus understood by a significant minority, although studied only slightly in school.

Religion

| Religion in Finland[130] | |||||||||||

| year | Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland | Finnish Orthodox Church | Other | No religious affiliation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1950 | 95.0% | 1.7% | 0.5% | 2.8% | |||||||

| 1980 | 90.3% | 1.1% | 0.7% | 7.8% | |||||||

| 1990 | 87.8% | 1.1% | 0.9% | 10.2% | |||||||

| 2000 | 85.1% | 1.1% | 1.1% | 12.7% | |||||||

| 2010 | 78.3% | 1.1% | 1.4% | 19.2% | |||||||

| 2014 | 73.9% | 1.1% | 1.6% | 23.5% | |||||||

| 2015 | 73.0% | 1.1% | 1.6% | 24.3% | |||||||

Approximately four million (or 73.0%[130] at the end of 2015) Finns are members of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland, which was disestablished in 1869 by the Church Act. It was the first state church to be disestablished in the Nordic countries, to be followed by the Church of Sweden in 2000. The Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland is one of the largest Lutheran churches in the world, although its share of the country's population has declined by roughly one percent annually in recent years.[130] The decline has been due to both church membership resignations and falling baptism rates.[131][132] The second largest group, accounting for 24.3% of the population[130] in 2015, has no religious affiliation. The irreligious group rose quickly from just below 13% in the year 2000. A small minority belongs to the Finnish Orthodox Church (1.1%). Other Protestant denominations and the Roman Catholic Church are significantly smaller, as are the Muslim, Jewish, and other non-Christian communities (totalling 1.6%). The main Lutheran and Orthodox churches are national churches of Finland with special roles such as in state ceremonies and schools.[133]

In 1869, Finland was the first Nordic country to disestablish its Evangelical Lutheran church by introducing the Church Act. Although the church still maintains a special relationship with the state, it is not described as a state religion in the Finnish Constitution or other laws passed by the Finnish Parliament.[134] Finland's state church was the Church of Sweden until 1809. As an autonomous Grand Duchy under Russia 1809–1917, Finland retained the Lutheran State Church system, and a state church separate from Sweden, later named the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland, was established. It was detached from the state as a separate judicial entity when the new church law came to force in 1869. After Finland had gained independence in 1917, religious freedom was declared in the constitution of 1919 and a separate law on religious freedom in 1922. Through this arrangement, the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland lost its position as a state church but gained a constitutional status as a national church alongside the Finnish Orthodox Church, whose position however is not codified in the constitution.

In 2014, 72.4% of Finnish children were baptized[135] and 82.3% were confirmed in 2012 at the age of 15,[136] and over 90% of the funerals are Christian. However, the majority of Lutherans attend church only for special occasions like Christmas ceremonies, weddings, and funerals. The Lutheran Church estimates that approximately 1.8% of its members attend church services weekly.[137] The average number of church visits per year by church members is approximately two.[138]

According to a 2010 Eurobarometer poll, 33% of Finnish citizens responded that "they believe there is a God"; 42% answered that "they believe there is some sort of spirit or life force"; and 22% that "they do not believe there is any sort of spirit, God, or life force".[139] According to ISSP survey data (2008), 8% consider themselves "highly religious", and 31% "moderately religious". In the same survey, 28% reported themselves as "agnostic" and 29% as "non-religious".[140]

Health

Life expectancy has increased from 71 years for men and 79 years for women in 1990 to 78 years for men and 84 years for women in 2012.[141] The under-five mortality rate has decreased from 51 per 1,000 live births in 1950 to 3 per 1,000 live births in 2012 ranking Finland’s rate among the lowest in the world.[142][143] The fertility rate in 2014 stood at 1,71 children born/per woman and has been below the replacement rate of 2.1 since 1969.[144] With a low birth rate women also become mothers at a later age, the mean age at first live birth being 28.6 in 2014.[144]

There has been a slight increase or no change in welfare and health inequalities between population groups in the 21st century. Lifestyle-related diseases are on the rise. More than half a million Finns suffer from diabetes, type 1 diabetes being globally the most common in Finland. Many children are diagnosed with type 2 diabetes. The number of musculoskeletal diseases and cancers are increasing, although the cancer prognosis has improved. Allergies and dementia are also growing health problems in Finland. One of the most common reasons for work disability are due to mental disorders, in particular depression.[145]

There are 307 residents for each doctor.[146] About 19% of health care is funded directly by households and 77% by taxation.

A recent study by The Lancet medical journal found that Finland has the lowest stillbirth rate out of 193 countries, including UK, France, and New Zealand.[147][148] In April 2012, Finland was ranked 2nd in Gross National Happiness in a report published by The Earth Institute.[149]

Education and science

Most pre-tertiary education is arranged at municipal level. Even though many or most schools were started as private schools, today only around 3 percent of students are enrolled in private schools (mostly specialist language and international schools), much less than in Sweden and most other developed countries.[150] Pre-school education is rare compared with other EU countries and formal education is usually started at the age of 7. Primary school takes normally six years and lower secondary school three years. Most schools are managed by municipal officials.

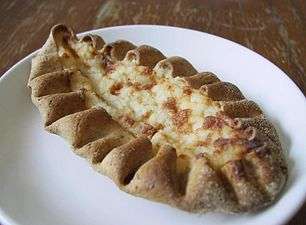

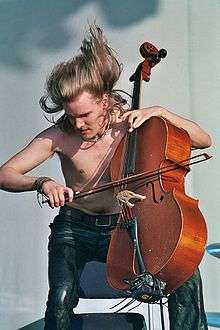

The flexible curriculum is set by the Ministry of Education and the Education Board. Education is compulsory between the ages of 7 and 16. After lower secondary school, graduates may either enter the workforce directly, or apply to trade schools or gymnasiums (upper secondary schools). Trade schools offer a vocational education: approximately 40% of an age group choose this path after the lower secondary school.[151] Academically oriented gymnasiums have higher entrance requirements and specifically prepare for Abitur and tertiary education. Graduation from either formally qualifies for tertiary education.