Religion in Turkey

Religion in Turkey  |

|---|

| Secularism in Turkey |

|

Minor religions |

| Irreligion in Turkey |

.jpg)

Islam is the largest religion in Turkey according to the state, with 99.8% of the population being automatically registered by the state as Muslim, for anyone whose parents are not of any other officially recognised religion,[2] while other sources give a little lower estimate of 96.4%.[3][4] Due to the nature of this method, the official number of Muslims include people with no religion; converted Christians/Judaists; people who are of a different religion than Islam, Christianity or Judaism; and anyone who is of a different religion than their parents, but has not applied for a change of their individual records. The state currently does not allow the individual records to be changed to anything other than Islam, Christianity or Judaism, and the latter two are only accepted with a document of recognition released by an officially recognised church or synagogue.

Recent independent polls show dramatically lower percentages, with 9.4% being not religious at all. The same studies show that roughly 90% of irreligious people are younger than the age of 35.[5] Most Muslims in Turkey are Sunnis forming about 72%, and Alevis belonging to Shia denomination form about 25% of the Muslim population.[6] There is also a Twelver Shia community which forms about 3% of the Muslim population. Among Shia Muslim presence in Turkey there is a small but considerable minority of Muslims with Ismaili heritage and affiliation.[7] Christians (Oriental Orthodoxy, Greek Orthodox and Armenian Apostolic) and Jews (Sephardi), who comprise the non-Muslim religious population, make up 0.2% of the total.[4][8][9]

Turkey is officially a secular country with no official religion since the constitutional amendment in 1924 and later strengthened by Atatürk's Reforms and the appliance of laïcité by the country's founder and first president Mustafa Kemal Atatürk at the end of 1937. However, currently all public schools from elementary to high school hold mandatory religion classes which only focus on the Sunni sect of Islam. In these classes, children are required to learn prayers and other religious practices which belong specifically to Sunnism. Thus, although Turkey is officially a secular state, the teaching of religious practices in public grade schools has been controversial. Its application to join the European Union divided existing members, some of which questioned whether a Muslim country could fit in. Turkish politicians have accused the country's EU opponents of favouring a "Christian club".[10]

Beginning in the 1980s, the role of religion in the state has been a divisive issue, as influential religious factions challenged the complete secularization called for by Kemalism and the observance of Islamic practices experienced a substantial revival. In the early 2000s (decade), Islamic groups challenged the concept of a secular state with increasing vigor after Recep Tayyip Erdoğan's Islamist-rooted Justice and Development Party (AKP) came into power in 2002.

Although the Turkish government states that more than 99% of the population is nominally Muslim, academic research and polls give different results of the percentage of Muslims which are usually lower, most of which are above the 90% range. In a poll conducted by Sabancı University, 98.3% of Turks revealed they were Muslim.[11] A poll conducted by Eurobarometer, KONDA and some other research institutes in 2013 showed that around 4.5 million of the 15+ population had no religion. Another poll conducted by the same institutions in 2015 showed that the number has reached 5.5 million, which means roughly 9.4% of the population in Turkey have no religion at all.[5]

Islam

Islam is the religion with the largest community of followers in the country, where most of the population is nominally Muslim,[12] of whom over 70% belong to the Sunni branch of Islam, predominantly following the Hanafi fiqh. Over 20% of the population belongs to the Alevi faith, thought by most of its adherents to be a form of Shia Islam; a minority consider it to have different origins (see Ishikism, Yazdanism). Closely related to Alevism is the small Bektashi community belonging to a Sufi order of Islam that is indigenous to Turkey, but also has numerous followers in the Balkan peninsula. The Ahmadiyya Muslim Community has a presence in eight districts of the country.[13]

Islam arrived in the region that comprises present-day Turkey, particularly the eastern provinces of the country, as early as the 7th century. The mainstream Hanafi school of Sunni Islam is largely organized by the state through the Presidency of Religious Affairs (known colloquially as Diyanet), which was established in 1924 following the abolition of the Ottoman Caliphate and controls all mosques and Muslim clerics, and is officially the highest religious authority in the country.[14]

As of today, there are thousands of historical mosques throughout the country which are still active. Notable mosques built in the Seljuk and Ottoman periods include the Sultan Ahmed Mosque and Süleymaniye Mosque in Istanbul, the Selimiye Mosque in Edirne, the Yeşil Mosque in Bursa, the Alâeddin Mosque and Mevlana Mosque in Konya, and the Great Mosque in Divriği, among many others. Large mosques built in the Republic of Turkey period include the Kocatepe Mosque in Ankara and the Sabancı Mosque in Adana.

Other religions

The remainder of the population belongs to other faiths, particularly Christian denominations (Eastern Orthodox, Armenian Apostolic, Syriac Orthodox, Catholic and Protestant), and Judaism (mostly Sephardi Jews, and a smaller Ashkenazi community.)[15]

Turkey has numerous important sites for Judaism and Christianity, being one of the birth places of the latter. Since the 4th century, Istanbul (Constantinople) has been the seat of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople (unofficially Fener Rum Ortodoks Patrikhanesi), which is one of the fourteen autocephalous Eastern Orthodox churches, and the primus inter pares (first among equals) in the Eastern Orthodox communion.[16] However, the Turkish government does not recognize the ecumenical status of Patriarch Bartholomew I. The Halki seminary remains closed since 1971 due to the Patriarchate's refusal to accept the supervision of the Turkish Ministry of Education on the school's educational curricula; whereas the Turkish government wants the school to operate as a branch of the Faculty of Theology at Istanbul University.[17] Other Eastern Orthodox denomination is the Turkish Orthodox Patriarchate with strong influences from Turkish nationalist ideology.

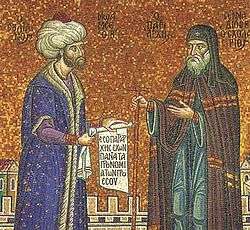

Istanbul, since 1461, is the seat of the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople. There have been 84 individual Patriarchs since establishment of the Patriarchate. The first Armenian Patriarch of Constantinople was Hovakim I who ruled from 1461 to 1478. Sultan Mehmed II allowed the establishment of the Patriarchate in 1461, just eight years after the Fall of Constantinople in 1453. The Patriarch was recognized as the religious and secular leader of all Armenians in the Ottoman Empire, and carried the title of milletbaşı or ethnarch as well as patriarch. 75 patriarchs have ruled during the Ottoman period (1461-1908), 4 patriarchs in the Young Turks period (1908–1922) and 5 patriarchs in the current secular Republic of Turkey (1923–present). The current Armenian Patriarch is Mesrob II (Mutafyan) (Մեսրոպ Բ. Մութաֆեան), who has been in office since 1998.

There are many churches and synagogues throughout the country, such as the Church of St. George, the St. Anthony of Padua Church, the Cathedral of the Holy Spirit, the Neve Shalom Synagogue, the Italian Synagogue and the Ashkenazi Synagogue in Istanbul. There are also many historical churches which have been transformed into mosques or museums, such as the Hagia Sophia and Chora Church in Istanbul, the Church of St. Peter in Antakya, and the Church of St. Nicholas in Myra, among many others. There is a small ethnic Turkish Protestant Christian community include about 4,000-5,000[18] adherents, most of them came from Muslim Turkish background.[19][20][21][22]

The Bahá'í Faith in Turkey has roots in Bahá'u'lláh's, the founder of the Bahá'í Faith, being exiled to Constantinople, current-day Istanbul, by the Ottoman authorities. Bahá'ís cannot register with the government officially,[23] but there are probably 10[24] to 20[25] thousand Bahá'ís, and around a hundred Bahá'í Local Spiritual Assemblies in Turkey.[26]

Secularism

Turkey has a secular constitution, with no official state religion.[27] The strong tradition of secularism in Turkey is essentially similar to the French model of laïcité, with the main distinction being that the Turkish state "openly and publicly controls Islam through its State Directorate of Religious Affairs".[28] The constitution recognizes the freedom of religion for individuals, whereas the religious communities are placed under the protection and jurisdiction of the state and cannot become involved in the political process (e.g. by forming a religious party) or establish faith-based schools. No political party can claim that it represents a form of religious belief; nevertheless, religious sensibilities are generally represented through conservative parties.[29][30] Turkey prohibits by law the wearing of religious headcover and other theopolitical symbolic garments (such as cross necklaces) for both genders in government buildings, schools, and public universities;[31] the law was upheld by the Grand Chamber of the European Court of Human Rights as "legitimate" in the Leyla Şahin v. Turkey case on November 10, 2005.[32]

Separation between mosque and state was established in Turkey soon after its founding in 1923, with an amendment to the Turkish constitution that mandated that Turkey had no official state religion and that the government and the state were to be free of religious influence. The modernizing reforms undertaken by President Mustafa Kemal Atatürk in the 1920s and 1930s further established secularism in Turkey.

Despite its official secularism, the Turkish government includes the state agency of the Presidency of Religious Affairs (Turkish: Diyanet İşleri Başkanlığı),[33] whose purpose is stated by law "to execute the works concerning the beliefs, worship, and ethics of Islam, enlighten the public about their religion, and administer the sacred worshiping places".[34] The institution, commonly known simply as Diyanet, operates 77,500 mosques, builds new ones, pays the salaries of imams, and approves all sermons given in mosques in Turkey.[35] The Presidency of Religious Affairs finances only Sunni Muslim worship in Turkey. For example, Alevi, Câferî (mostly Azeris), and Bektashi Muslims (mostly Turkmen) participate in the financing of the mosques and the salaries of Sunni imams by paying taxes to the state, while their places of worship, which are not officially recognized, do not receive any state funding. The Presidency of Religious Affairs' budget rose from USD $0.9 billion for the year 2006 to $2.5 billion in 2012.

Beginning in the 1980s, the role of religion in the state has been a divisive issue, as influential religious factions challenged the complete secularization called for by Kemalism and the observance of Islamic practices experienced a substantial revival. In the early 2000s (decade), Islamic groups challenged the concept of a secular state with increasing vigor after Recep Tayyip Erdoğan's Islamist-rooted Justice and Development Party (AKP) came into power in 2002.

Turkey, through the Treaty of Lausanne (1923), recognizes the civil, political, and cultural rights of non-Muslim minorities. In practice, Turkey only recognizes Greek, Armenian, and Jewish religious minorities. Alevi, Bektashi, and Câferî Muslims among other Muslim sects,[36] as well as Latin Catholics and Protestants, are not recognized officially. In 2013, the European Court of Human Rights ruled that Turkey had discriminated against the religious freedom of Alevis.[37]

With more than 100,000 employees, the Presidency of Religious Affairs has been described as state within the state.[38] Its budget is compared with the budgets of other state departments as such:

- 1.6 times larger than the budget allocated to the Ministry of the Interior[39]

- 1.8 times larger than the budget allocated to the Ministry of Health[39]

- 1.9 times larger than the budget allocated to the Ministry of Industry, Science and Technology[39]

- 2.4 times larger than the budget allocated to the Ministry of Environment and Urban Planning[39]

- 2.5 times larger than the budget allocated to the Ministry of Culture and Tourism[39]

- 2.9 times larger than the budget allocated to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs[39]

- 3.4 times larger than the budget allocated to the Ministry of Economy[39]

- 3.8 times larger than the budget of the Ministry of Development[39]

- 4.6 times larger than the budget allocated to MIT – Secret Services [39]

- 5,0 times larger than the budget allocated to the Department of Emergency and Disaster Management[39]

- 7.7 times larger than the budget allocated to the Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources[39]

- 9.1 times larger than the budget allocated to the Ministry of Customs and Trade[39]

- 10.7 times greater than the budget allocated to Coast Guard[39]

- 21.6 times greater than the budget allocated to the Ministry of the European Union[39]

- 242 times larger than the budget for the National Security Council[39]

- 268 times more important than the budget allocated to the Ministry of Public Employee[39]

Diyanet's budget represents:

- 79% of the budget of the police[39]

- 67% of the budget of the Ministry of Justice[39]

- 57% of the budget of public hospitals[39]

- 31% of the budget of the National Police[39]

Situation of Religions

| Religions | Estimated population | Expropriation measures[40] |

Official recognition through the Constitution or international treaties | Government Financing of places of worship and religious staff |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sunni Islam - Hanafi | 70% (56,000,000) | No | Yes through the Diyanet mentioned in the Constitution (art.136) [41] | Yes through the Diyanet [42] |

| Sunni Islam - Shafi'i | ||||

| Shia Islam - Alevism[43] | 25% (20,000,000) | Yes[36] | Only by local municipalities, not constutituonal [44] | Yes through some local municipalities [44] |

| Shia Islam - Ja'fari | 4% (3,200,000) [45] | No[46] | No[46] | |

| Shia Islam - Alawism[43] | 1% (800,000) [47] | No [46] | No [42] | |

| Christianity - Armenian Orthodoxy | 65,000 | Yes [40] | Yes through the Treaty of Lausanne (1923)[46] | No [42] |

| Judaism | 20,000 | Yes [40] | Yes through the Treaty of Lausanne (1923)[46] | No [42] |

| Christianity - Latin Catholicism | 20,000 | No [46] | No [42] | |

| Christianity - Syriac Orthodoxy | 15,000 | Yes [40] | No [46] | No [42] |

| Christianity - Melkite Orthodoxy | 10,000 | Yes [48] | Yes through the Treaty of Lausanne (1923)[46] | No [42] |

| Christianity - Chaldean Catholicism | 8,000 | Yes [40] | No [46] | No [42] |

| Christianity - Greek Orthodoxy | 5,000 | Yes [40] | Yes through the Treaty of Lausanne (1923)[46] | No [42] |

| Christianity - Armenian Catholicism | 3,500 | Yes [40] | Yes through the Treaty of Lausanne (1923)[46] | No [42] |

| Christianity - Syriac Catholicism | 2,000 | Yes [40] | No [46] | No [42] |

| Christianity - Armenian Protestantism | 1,500 | Yes [40] | Yes through the Treaty of Lausanne (1923)[46] | No [42] |

| Tengrism | 1,000 | No [46] | No [42] | |

| Yazidism | 500 | No [46] | No [42] | |

| Christianity - Turkish Orthodoxy | 400 | Yes through the Treaty of Lausanne (1923)[46] | No [42] | |

| Christianity - Greek Catholicism | 50 | Yes [40] | Yes through the Treaty of Lausanne (1923)[46] | No [42] |

Religious organization

The mainstream Hanafite school of Sunni Islam is largely organised by the state, through the Presidency of Religious Affairs (Turkish: Diyanet İşleri Başkanlığı), which controls all mosques and pays the salaries of all Muslim clerics. The directorate is criticized by some Alevi Muslims for not supporting their beliefs and instead favoring only the Sunni faith.

The Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople (Patrik) is the head of the Greek Orthodox Church in Turkey, and also serves as the spiritual leader of all Orthodox churches throughout the world. The Armenian Patriarch is the head of the Armenian Church in Turkey, while the Jewish community is led by the Hahambasi, Turkey's Chief Rabbi, based in Istanbul. These groups have also criticized the Presidency of Religious Affairs for only financially supporting Islam in Turkey.

Historical Christian sites

Antioch (modern Antakya), the city where "the disciples were first called Christians" according to the biblical Book of Acts, is located in modern Turkey, as are most of the areas visited by St. Paul during his missions. The Epistle to the Galatians, Epistle to the Ephesians, Epistle to the Colossians, First Epistle of Peter, and Book of Revelation are addressed to recipients in the territory of modern Turkey. Additionally, all of the first Seven Ecumenical Councils that define Christianity for Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholic Christians took place in the territory that is now Turkey. Many titular sees exist in Turkey, as Anatolia was historically home to a large Christian population for centuries.

Freedom of religion

The Constitution provides for freedom of religion, and Turkey is a party to the European Convention on Human Rights.[49][49]

Turkey has a democratic government and a strong tradition of secularism. Nevertheless, the Turkish state's interpretation of secularism has reportedly resulted in religious freedom violations for some of its non-Muslim citizens. The 2009 U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom report placed Turkey on its watchlist with countries such as Afghanistan, Cuba, the Russian Federation, and Venezuela.[50] Nevertheless, according to this report, the situation for Jews in Turkey is better than in other majority Muslim countries. Jews report being able to worship freely and their places of worship having the protection of the government when required. Jews also operate their own schools, hospitals, two elderly homes, welfare institutions, as well as a newspaper. Despite this, concerns have arisen in recent years because of attacks by extremists on synagogues in 2003, as well as growing anti-Semitism in some sectors of the Turkish media and society.

Roman Catholics have also occasionally been subjected to violent societal attacks. In February 2006, an Italian Catholic priest was shot to death in his church in Trabzon, reportedly by a youth angered over the caricatures of Muhammad in Danish newspapers. The government strongly condemned the killing. A 16-year-old boy was subsequently charged with the murder and sentenced to 19 years in prison. In December 2007, a 19-year-old stabbed a Catholic priest outside a church in İzmir; the priest was treated and released the following day. According to newspaper reports, the assailant, who was arrested soon afterwards, admitted that he had been influenced by a recent television program that depicted Christian missionaries as "infiltrators" who took advantage of poor people.

The Armenian Patriarch, head of the Armenian Orthodox Church, also lacks the status of legal personality (unlike the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople, who has a government-recognized role), and there is no seminary in Turkey to educate its clerics since the closure of the last remaining seminar by the state, as only 65,000 Armenian Orthodox people live in Turkey. In 2006, the Armenian Patriarch submitted a proposal to the Minister of Education to enable his community to establish a faculty in the Armenian language at a state university with instruction by the Patriarch. Under current restrictions, only the Sunni Muslim community can legally operate institutions to train new clergy in Turkey for future leadership.

Patriarch Bartholomew I, most senior bishop among equals in the traditional hierarchy of Orthodox Christianity, said that he felt "crucified" living in Turkey under a government that did not recognize the ecumenical status of Patriarch and which would like to see his Patriarchate die out.[51] The AKP government under Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan criticized Bartholomew I, with deputy prime minister Arınç saying that the Orthodox Church enjoyed their religious rights during the AKP's rule, and foreign minister Davutoğlu saying that he hoped that the Patriarch's remarks had been a "slip of the tongue".[52][53] In response to the government's criticism, Bartholomew's lawyer said when the patriarchate was criticizing government, he was referring to the state, not the AKP government in particular.[54] Prime Minister Erdoğan said that “When it comes to the question, 'Are you recognizing [him] as ecumenical?', I wouldn’t be annoyed by it [this title]. Since it did not annoy my ancestors, it will not annoy me, either. But it may annoy some [people] in my country".[55] The Greek Orthodox orphanage in Büyükada was closed by the government;[56] however, following a ruling by the European Court of Human Rights, the deed to the orphanage was returned to the Ecumenical Patriarchate on November 29, 2010.[57]

Religiosity

In the most recent poll conducted by Sabancı University, 98.3% of Turks revealed they were Muslim.[11] Of that, 16% said they were "extremely religious", 39% said they were "somewhat religious", and 32% said they were "not religious".[11] 3% of Turks declare themselves with no religious beliefs.[11]

A Pew Research Center report in 2002 found that 65% of the people in Turkey say religion plays a very important role in their lives.[58]

According to the Eurobarometer Poll 2010:[59]

- 94% of Turkish citizens responded: "I believe there is a God".

- 1% responded: "I believe there is some sort of spirit or life force".

- 1% responded: "I do not believe there is any sort of spirit, god, or life force".

According to the KONDA Research and Consultancy survey carried out throughout Turkey on 2007:[60]

- 52.8% defined themselves as "a religious person who strives to fulfill religious obligations" (Religious)

- 34.3 % defined themselves as ""a believer who does not fulfill religious obligations" (Not religious).

- 9.7% defined themselves as "a fully devout person fulfilling all religious obligations" (Fully devout).

- 2.3% defined themselves as "someone who does not believe in religious obligations" (Non-believer).

- 0.9% defined themselves as "someone with no religious conviction" (Atheist).

Increased Islamic religiosity

The rise of Islamic religiosity in Turkey in the last two decades has been discussed for the past several years.[61][62][63] Many see Turkish society moving towards a more hardline Islamic identity and country,[61][63] citing increasing religious criticisms against what is considered immoral behavior and government policies seen as enforcing conservative Islamic morality, including mandates of wearing modest clothing and banning of lipstick and nail polish for airline hostesses,[64] as well as the controversial blasphemy conviction of the pianist Fazıl Say for "insulting Islam" by retweeting a joke about the Islamic Friday prayer. The New York Times published a report about Turkey in 2012, noting an increased polarization between secular and religious groups in Turkish society and politics. Critics argue that Turkish public institutions, once staunchly secular, are shifting in favor of Islamists.[62]

Headscarf controversy

Current Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan, whose Justice and Development Party (AKP) traces its roots to a series of banned Islamist parties (specifically Virtue Party, Welfare Party, and National Salvation Party), campaigned in his victorious 2007 campaign with a promise of lifting the longstanding ban on headscarves in public governmental institutions.[65]

On February 7, 2008, the Turkish Parliament passed an amendment to the constitution, allowing women to wear the headscarf in Turkish universities, arguing that many women would not seek an education if they could not wear the headscarf. The ruling AKP and a key opposition party, the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), claimed that it was an issue of human rights and freedoms.[66][67][68][69]

Restriction of alcohol sales and advertising

In 2013, the parliament of Turkey passed legislation that bans all forms of advertising for alcoholic beverages and tightened restriction of alcohol sales.[70] This also includes the blurring of images on television. The law was sponsored by the ruling AKP.

Books in school

In 2013, several books that were previously recommend for classroom use were found to be rewritten to include more Islamic themes, without the Ministry of Education's consent. Traditional stories of Pinocchio, Heidi, and Tom Sawyer were rewritten to include characters that wished each other a "God-blessed morning" and statements that included "in Allah's name"; in one rewrite, one of the Three Musketeers converted to Islam.[71]

See also

References

- ↑ "Turkey". Joshua Project. Retrieved 2015-04-04.

- ↑ "Turkey". World Factbook. CIA. 2007.

- ↑ "Country - Turkey". Joshua Project. Retrieved 27 April 2014.

- 1 2 United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. "Refworld | Country Profile - Turkey". Unhcr.org. Retrieved 2016-01-31.

- 1 2 "Türkiye'deki Ateist Nüfus Hızla Artıyor". onedio.com. Retrieved 2016-01-31.

- ↑ Zeidan, David (December 1995). "The Alevi of Anatolia". angelfire.com. Archived from the original on 23 April 2012.

- ↑ "Shi'a". Philtar.ucsm.ac.uk. Retrieved 2016-01-31.

- ↑ Shankland, David (2003). The Alevis in Turkey: The Emergence of a Secular Islamic Tradition. Routledge (UK). p. 20. ISBN 0-7007-1606-8.

Some [researchers] claim that the number of Alevis is as high as 30 per cent of Turkey's population. Others state that there are as few as 10 per cent.

- ↑ "Turkey - A Brief Profile". United Nations Population Fund. 2006. Retrieved 2006-12-27.

- ↑ "BBC NEWS - Europe - Muslims in Europe: Country guide". Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- 1 2 3 4

- ↑ "Turkey". State.gov. Retrieved 2016-01-31.

- ↑ "MEMBERS OF THE AHMADIYYA MUSLIM COMMUNITY DR MUHAMMED JALAL SHAMS, OSMAN SEKER, KUBILAY ÇIL: PRISONERS OF CONSCIENCE FOR THEIR RELIGIOUS BELIEFS". Amnesty International. June 5, 2002. Retrieved June 10, 2014.

- ↑ "Basic Principles, Aims And Objectives". diyanet.gov.tr. Archived from the original on 19 December 2011.

- ↑ "Turkey - A Brief Profile". United Nations Population Fund. 2006. Archived from the original on 19 July 2007. Retrieved 27 December 2006.

- ↑ "The Patriarchate of Constantinople (The Ecumenical Patriarchate)". cnewa.org. 30 May 2008. Archived from the original on 9 January 2010.

- ↑ "The Patriarch Bartholomew". 60 Minutes. CBS. 20 December 2009. Retrieved 11 January 2010.

- ↑ [http://www.iirf.eu/index.php?id=178&no_cache=1&tx_ttnews[backPid]=176&tx_ttnews[tt_news]=1295 "International Institute for Religious Freedom: Single Post"]. Iirf.eu. Retrieved 2016-01-31.

- ↑ "Turkish Protestants still face "long path" to religious freedom - The Christian Century". The Christian Century. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ↑ "TURKEY - Christians in eastern Turkey worried despite church opening". Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ↑ "Muslim Nationalism and the New Turks". Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ↑ "TURKEY: Protestant church closed down - Church In Chains - Ireland :: An Irish voice for suffering, persecuted Christians Worldwide". Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ↑ U.S. State Department (19 September 2008). "International Religious Freedom Report 2008: Turkey". The Office of Electronic Information, Bureau of Public Affairs. Retrieved 15 December 2008.

- ↑ "For the first time, Turkish Baha'i appointed as dean". The Muslim Network for Baha'i Rights. 13 December 2008. Retrieved 15 December 2008.

- ↑ "Turkey: Religions & Peoples". LookLex Encyclopedia. LookLex Ltd. 2008. Retrieved 15 December 2008.

- ↑ Walbridge, John (March 2002). "Chapter Four: The Baha'i Faith in Turkey". Occasional Papers in Shaykhi, Babi and Baha'i Studies. 6 (1).

- ↑ "BBC NEWS - Europe - Headscarf row goes to Turkey's roots". Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ↑ "EUI Working Papers : RSCAS 2008/20 : Mediterranean Programme Series". Cadmus.eui.eu. Retrieved 2016-01-31.

- ↑ "Headscarf row goes to Turkey's roots". BBC News. 2003-10-29. Retrieved 2006-12-13.

- ↑ Çarkoglu, Ali; Rubin, Barry (2004). Religion and Politics in Turkey. Routledge (UK). ISBN 0-415-34831-5.

- ↑ "The Islamic veil across Europe". British Broadcasting Corporation. 2006-11-17. Retrieved 2006-12-13.

- ↑ European Court of Human Rights (2005-11-10). "Leyla Şahin v. Turkey". ECHR. Retrieved 2006-11-30.

- ↑ "T.C. Diyanet İşleri Başkanlığı - İman - İbadet - Namaz - Ahlak". Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ↑ "Establishment and a Brief History". Diyanet.gov.tr. Retrieved 2016-01-31.

- ↑ Samim Akgönül - Religions de Turquie, religions des Turcs: nouveaux acteurs dans l'Europe élargie - L'Harmattan - 2005 - 196 pages

- 1 2 The World of the Alevis: Issues of Culture and Identity, Gloria L. Clarke

- ↑ "Turkey 'guilty of religious discrimination'". Al Jazeera English. 2014-12-04. Retrieved 2016-01-31.

- ↑ "La politique turque en question: entre imperfections et adaptations - Emel Parlar Dal - Google Books". Books.google.com. 2012-11-01. Retrieved 2016-01-31.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 "2013 Yılı Merkezı Yönetım Bütçe Kanunu Tasarısı ve bağlı cetveller" [2013 Central Government Budget Draft Law and its rules] (PDF). The Grand National Assembly of Turkey (in Turkish). 2013. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Le gouvernement turc va restituer des biens saisis à des minorités religieuses". La Croix. 2011-08-29. Retrieved 2016-01-31.

- ↑ (Turkish) http://www.tbmm.gov.tr/anayasa/anayasa_2011.pdf

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Cahiers de l'obtic (December 2012). "La Présidence des affaires religieuses (Diyanet): au carrefour de l'islam, de l'action étatique et de la politique étrangère turque" [Presidency of Religious Affairs (Diyanet): At the Crossroads of Islam, State action, and Turkish foreign policy] (PDF) (in French). Observatory of Interdisciplinary Research on Contemporary Turkey (OBTIC). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 October 2013.

- 1 2 Not recognized as an Islamic fiqh madh'hab by the Amman Message.

- 1 2 "cemevi ibadethane kabul edildi Haberleri ve cemevi ibadethane kabul edildi Gelişmeleri". Milliyet. 2013-01-31. Retrieved 2016-01-31.

- ↑ Rapport Minority Rights Group Bir eşitlik arayışı: Türkiye’de azınlıklar Uluslararası Azınlık Hakları Grubu 2007 Dilek Kurban

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 par Lisa Deheurles-Montmayeur · 18 avril 2010. "Les minorités non musulmanes en Turquie : "certains rapports d'ONG parlent d'une logique d'attrition", observe Jean-Paul Burdy – Observatoire de la vie politique turque". Ovipot.hypotheses.org. Retrieved 2016-01-31.

- ↑ "Dünyada ve Türkiye'de Nusayrilik" [Turkey and Nusayri in the world] (in Turkish). psakd.org. 16 August 2006. Archived from the original on 17 December 2011.

- ↑ "Rum Orthodox Christians". minorityrights.org. 5 February 2005. Archived from the original on 16 January 2015.

- 1 2 "Turkey". International Religious Freedom Report 2007. U.S. Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor. 2007-09-14. Retrieved 2008-08-19.

- ↑ "Annual Report of the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom" (PDF). U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom. May 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 May 2009.

- ↑ "The Patriarch Bartholomew". 60 Minutes. CBS News. 20 December 2009. Retrieved 11 January 2010.

- ↑ "Government Spokesman Criticizes Greek Patriarch Over Crucifixion Remarks". Turkishpress.com. 21 December 2009. Retrieved 17 August 2010.

- ↑ "Gül backs minister's criticism of Patriarch Bartholomew". Today's Zaman. 22 December 2009. Retrieved 17 August 2010.

- ↑ "Bartholomew crucified, Erdoğan suffers from Hellish torture!(1)". Today's Zaman. 25 December 2009. Retrieved 17 August 2010.

- ↑ "Greece, Turkey mark a fresh start aimed at eventual partnership". Today's Zaman. 17 May 2010. Retrieved 17 August 2010.

- ↑ "The Greek Orthodox Church In Turkey: A Victim Of Systematic Expropriation". United States Commission On Security And Cooperation In Europe. 16 March 2005. Retrieved 10 May 2010.

- ↑ Selcan Hacaoğlu (November 29, 2010). "Turkey gives orphanage to Ecumenical Patriarchate". The Washington Post.

- ↑ "Religion is very important". Global Attitudes Project. Pew Research Center. 2002-12-19. Retrieved 2002-12-19.

- ↑ "Special Eurobarometer, biotechnology, page 204" (PDF). 2010.

- ↑ KONDA Research and Consultancy (2007-09-08). "Religion, Secularism and the Veil in daily life" (PDF). Milliyet.

- 1 2 "Egypt, Turkey, and Tunisia Are All Slowly Islamizing". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2016-01-31.

- 1 2 "In Turkey, Forging a New Identity". International Herald Tribune. 1 December 2012. Retrieved 31 January 2016 – via The New York Times.

- 1 2 "The Region: Turkey trots toward Islamism". The Jerusalem Post - JPost.com. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ↑ "Air hostesses banned from wearing lipstick and nail polish in Turkey sparking row over increasing Islamic influence". Mail Online. 3 May 2013. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ↑ Simon Tisdall. "Recep Tayyip Erdogan: Turkey's elected sultan or an Islamic democrat?". the Guardian. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ↑ Ayman, Zehra; Knickmeyer, Ellen. Ban on Head Scarves Voted Out in Turkey: Parliament Lifts 80-Year-Old Restriction on University Attire. The Washington Post. 2008-02-10. Page A17.

- ↑ Derakhshandeh, Mehran. Just a headscarf? Tehran Times. Mehr News Agency. 2008-02-16.

- ↑ Jenkins, Gareth. Turkey's Constitutional Changes: Much Ado About Nothing? Eurasia Daily Monitor. The Jamestown Foundation. 2008-02-11.

- ↑ Turkish president approves amendment lifting headscarf ban. The Times of India. 2008-02-23.

- ↑ Ahren, Raphael (2013-05-24). "Turkey passes law restricting alcohol sales". The Times of Israel. Retrieved 2016-01-31.

- ↑ SPIEGEL ONLINE, Hamburg, Germany (2 November 2006). "Turkey in Transition: Less Europe, More Islam". SPIEGEL ONLINE. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

External links

- The Legal Status of the Ecumenical Patriarchate

- Turkey's delay in introducing protection for the rights of religious minorities