Reginald Pole

| His Eminence Reginald Pole | |

|---|---|

|

Cardinal Archbishop of Canterbury Primate of All England | |

| |

| Province | Canterbury |

| Diocese | Canterbury |

| See | Canterbury |

| Installed | 1556 |

| Term ended | 17 November 1558 |

| Predecessor | Thomas Cranmer |

| Successor | Matthew Parker |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

3 March 1500 Stourton Castle, Staffordshire Kingdom of England |

| Died |

17 November 1558 (aged 58) London, Kingdom of England |

| Buried | The Corona, Canterbury Cathedral, Kent |

| Nationality | English |

| Denomination | Roman Catholic |

| Parents |

Sir Richard Pole The Countess of Salisbury |

| Alma mater | Magdalen College, Oxford |

Reginald Pole (12 March 1500 – 17 November 1558) was an English cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church and the last Roman Catholic Archbishop of Canterbury, holding the office from 1556 to 1558, during the Counter Reformation.

Early career

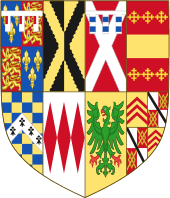

Pole was born at Stourton Castle, Staffordshire, on 12 March 1500.[1][2] to Sir Richard Pole and Margaret Pole, 8th Countess of Salisbury, and was their third son. His maternal grandparents were George Plantagenet, 1st Duke of Clarence, and Isabella Neville, Duchess of Clarence; thus he was a great-nephew of kings Edward IV and Richard III and a great-grandson of Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick.

Education

His nursery is said to have been at Sheen Priory.[3] He matriculated at Magdalen College, Oxford, in 1512, and at Oxford was taught by William Latimer and Thomas Linacre, graduating with a BA on 27 June 1515. In February 1518, King Henry VIII granted him the deanery of Wimborne Minster, Dorset; after which he was Prebendary of Salisbury and Dean of Exeter in 1527.[4] He was also a canon in York, and had several other livings, although he had not been ordained a priest. Assisted by Bishop Edward Foxe, he represented Henry VIII in Paris in 1529, researching general opinions among theologians of the Sorbonne about the annulment of Henry's marriage with Catherine of Aragon.[5]

In 1521, Pole went to the University of Padua, where he met leading Renaissance figures, including Pietro Bembo, Gianmatteo Giberti (formerly pope Leo X's datary and chief minister), Jacopo Sadoleto, Gianpietro Carafa (the future Pope Paul IV), Rodolfo Pio, Otto Truchsess, Stanislaus Hosius, Cristoforo Madruzzo, Giovanni Morone, Pier Paolo Vergerio the younger, Peter Martyr (Vermigli) and Vettor Soranzo. The last three were eventually condemned as heretics by the Roman Catholic Church, with Vermigli—as a well-known Protestant theologian—having a significant share in the Reformation in Pole's native England.

His studies in Padua were partly financed by his election as a fellow of Corpus Christi College, Oxford, with more than half of the cost paid by Henry VIII himself[6] on 14 February 1523, which allowed him to study abroad for three years.

Pole and Henry VIII

Pole returned home in July 1526, when he went to France, escorted by Thomas Lupset. Henry VIII offered him the Archbishopric of York or the Diocese of Winchester if he would support his divorce from Catherine of Aragon. Pole withheld his support and went into self-imposed exile in France and Italy in 1532, where he continued his studies in Padua and Paris. After his return he held the benefice of Vicar of Piddletown, Dorset, between 20 December 1532 and about January 1535/1536.[7]

In May 1536, Reginald Pole finally and decisively broke with the King. In 1531, he had warned of the dangers of the Boleyn marriage; he had returned to Padua in 1532, and received a last English benefice in December. Chapuys had suggested to Emperor Charles V that Pole marry the Lady Mary and combine their dynastic claims; Chapuys also communicated with Reginald through his brother Geoffrey.

The final break between Pole and Henry followed upon Thomas Cromwell, Cuthbert Tunstall, Thomas Starkey and others addressing questions to Pole on behalf of Henry. He answered by sending the king a copy of his published treatise Pro ecclesiasticae unitatis defensione, which, besides being a theological reply to the questions, was a strong denunciation of the king's policies that denied Henry's position on the marriage of a brother's wife and denied the Royal Supremacy; Pole also urged the Princes of Europe to depose Henry immediately. Henry wrote to the Countess of Salisbury, who in turn sent her son a letter reproving him for his "folly."[8]

The incensed king, with Pole himself out of his reach, took a terrible revenge on Pole's family. Although Pole's mother and his elder brother had written to him in reproof of Pole's attitude and action, he did not spare them.

.jpg)

Cardinal Pole

In 1537 Pole, already a deacon,[9] was created a cardinal. Pope Paul III put him in charge of organising assistance for the Pilgrimage of Grace (and related movements), an effort to organise a march on London to install a Roman Catholic government instead of Henry's; neither Francis I of France nor the Emperor supported this effort, and the English government tried to have Pole assassinated. In 1539, Pole was sent to the Emperor to organise an embargo against England – the sort of countermeasure he had himself warned Henry was possible.[5]

Sir Geoffrey Pole was arrested in August 1538; he had been corresponding with Reginald, and the investigation of Henry Courtenay, Marquess of Exeter (Henry VIII's first cousin and the Countess of Salisbury's second cousin) had turned up his name; he had appealed to Thomas Cromwell, who had him arrested and interrogated. Under interrogation, Sir Geoffrey said that Henry Pole, his eldest brother, Lord Montagu, and Exeter had all been parties to his correspondence with Reginald. Montagu, Exeter, and Lady Salisbury were arrested in November 1538, together with Henry Pole and other family members, on charges of treason, although Cromwell had previously written that they had "little offended save that he [Reginald Pole] is of their kin". They were committed to the Tower of London, and in January, with the exception of Geoffrey Pole, they were executed.

In January 1539, Sir Geoffrey was pardoned, and Montagu and Exeter were tried and executed for treason, while Reginald Pole was attainted in absentia. In May 1539, Montagu, Exeter, Countess Salisbury, and others were also attainted, as her father had been; this meant that they lost their lands – mostly in the South of England, conveniently located to assist any invasion – and titles, and those still alive in the Tower were also sentenced to death, so could be executed at the King's will. As part of the evidence given in support of the Bill of Attainder, Cromwell produced a tunic bearing the Five Wounds of Christ, symbolising Lady Salisbury's support of Roman Catholicism and the rule of Reginald and Mary; the supposed discovery, six months after her house and effects had been searched when she was arrested, is likely to be a fabrication.

Margaret Pole, as she was now called, was held in the Tower of London for two and a half years under severe conditions; she, her grandson (Montagu's son), and Exeter's son were held together and supported by the King. In 1540, Cromwell himself fell from favour and was himself executed and attainted. Margaret Pole was finally executed in 1541 (her execution was dreadfully botched and horrifying even for those brutal times), protesting her innocence until the last – a highly publicised case which was considered a grave miscarriage of justice both at the time and later. Pole is known to have said that he would "...never fear to call himself the son of a martyr". Some 350 years later, in 1886, Margaret was beatified by Pope Leo XIII.

| Styles of Reginald Pole | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reference style | His Eminence |

| Spoken style | Your Eminence |

| Informal style | Cardinal |

| See | Canterbury |

Aside from the aforementioned oppositional treatise, King Henry's harshness towards the Pole family might have derived from the fact that Pole's mother, Margaret, was one of the last surviving members of the House of Plantagenet. Under some circumstances, that descent could have made Reginald – until he definitely entered the clergy – a possible contender for the throne itself. Indeed, in 1535 Pole was considered by Eustace Chapuys, the Imperial ambassador to England, as a possible husband for Princess Mary, later Mary I of England.

Pole was made a cardinal by Pope Paul III in 1536, over Pole's own objections. He also became Papal Legate to England in February 1536/1537. In 1542 he was appointed as one of the three Papal Legates to preside over the Council of Trent, in 1549 he was appointed by Pope Paul III Abbot of Gavello or Canalnuovo, and after the death of Pope Paul III in 1549 Pole, at one point, had nearly the two-thirds of the vote he needed to become Pope himself[10] at the papal conclave of 1549–50. His personal belief in justification by faith over works had caused him problems at Trent and accusations of heresy at the conclave.

Later years

The death of Edward VI on 6 July 1553 and the accession of Mary I to the throne of England hastened Pole's return from exile, as Papal Legate to England (which he served as until 1557). In 1554, Cardinal Pole came to England to receive the kingdom back into the Roman fold. However, Mary and the Emperor Charles V delayed him until 20 November 1554, due to apprehension that Pole might oppose the Queen's forthcoming marriage to Charles's son, Philip of Spain.[11]

As Papal Legate, Pole negotiated a papal dispensation allowing the new owners of confiscated former monastic lands to retain them, and in return Parliament enabled the Revival of the Heresy Acts in January 1555.[12] This revived former measures against heresy: the letters patent of 1382 of Richard II, an Act of 1401 of Henry IV, and an Act of 1414 of Henry V. All of these had been repealed under Henry VIII and Edward VI.[13] On 13 November 1555, Cranmer was officially deprived of the See of Canterbury.[14]

Under Mary's rule, Pole, whose attainder was reversed in 1554, was finally ordained as a Priest on 20 March 1556 and consecrated as Archbishop of Canterbury two days later,[5] an office he would hold until his death. He was also Chancellor of both Oxford and Cambridge universities in 1555 and 1555/1556 respectively.[15] As well as his religious duties, he was in effect the Queen's chief minister and adviser. Many former enemies, including Cranmer, signed recantations affirming their religious belief in transubstantiation and papal supremacy.[16] Despite this, which should have absolved them under Mary's own Revival of the Heresy Acts, the Queen could not forget their responsibility for her mother's unhappy divorce.[17]

In 1555, Queen Mary began permitting the burning of Anglicans for heresy, and some 220 men and 60 women were executed before her death in 1558. Pole shares responsibility for these persecutions which, despite his intention, contributed to the ultimate victory of the English Reformation.[18] On the other hand, Pole was in failing health during the worst period of persecution, and there is some evidence that he favoured a more lenient approach: "Three condemned heretics from Bonner's diocese were pardoned on an appeal to him; he merely enjoined a penance and gave them absolution."[10] As the reign wore on, an increasing number of people turned against Mary and her government,[19] and some people who had been indifferent to the English Reformation began turning against Catholicism.[20][21] Writings such as John Foxe's 1568 Book of Martyrs, which emphasised the sufferings of the reformers under Mary, helped shape popular opinion against Catholicism in England for generations.[19][21]

Death

Pole died in London, during an influenza epidemic, on 17 November 1558, at about 7:00 pm, nearly 12 hours after Queen Mary's death from stomach cancer.[22] He was buried on the north side of the Corona at Canterbury Cathedral.

Author

Pole was the author of De Concilio and of treatises on the authority of the Roman Pontiff and the Anglican Reformation of England, and of many important letters, full of interest for the history of the time, edited by Angelo Maria Quirini.[23]

He is known for his strong condemnation of Machiavelli's book The Prince, which he read in Italy, and on which he commented: "I found this type of book to be written by an enemy of the human race. It explains every means whereby religion, justice and any inclination toward virtue could be destroyed".[24]

In popular culture

Cardinal Pole is a major character in the historical novel The Trusted Servant by Alison Macleod.[25]

In Season 3 of Showtime's series The Tudors, Cardinal Pole is portrayed by Canadian actor Mark Hildreth. In the mini-series The Virgin Queen he is played by Michael Feast; he is last seen leading Mary's servants out of Greenwich Palace as Elizabeth arrives as Queen.

Ancestors

References

- ↑ White, William (1834). History, Gazetteer and Directory of Staffordshire. Sheffield. p. 261.

- ↑ He was named after the now Blessed Reginald of Orleans, O.P.

- ↑ Thornbury, Walter. Old & New London: A Narrative of its History, its People and its Places. London, undated, post 1872. (6 Vols.) Vol.2, p.553. The Holborn Inns of Court, Denys bequest to Sheen.

- ↑ "Britannia Biographies". Britannia.com. Retrieved 5 December 2011.

- 1 2 3 "Pole, Reginald". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/22456. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ http://www.lambethpalacelibrary.org/files/Reginald_Pole_0.pdf[]

- ↑ Emden, Alfred Brotherston (1974). A biographical register of the University of Oxford, A.D. 1501 to 1540. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 453. ISBN 0199510083.

- ↑ ODNB, "Reginald Pole"; "Geoffrey Pole". Pole and his hagiographers gave several later accounts of Pole's activities after Henry met Anne Boleyn. These are not consistent; and if – as he claimed at one point – Pole rejected the divorce in 1526 and refused the Oath of Supremacy in 1531, he received benefits from Henry for a course of action for which others were sentenced to death.

- ↑ "Reginald Cardinal Pole (Catholic-Hierarchy)". Catholic-hierarchy.org. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- 1 2

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Reginald Pole". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Reginald Pole". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. - ↑

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Mary Tudor". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Mary Tudor". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. - ↑ Bucholz, R. O.; Key, N. (2009). Early modern England 1485–1714: a narrative history. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 110–111. ISBN 978-1-4051-6275-3.

- ↑ Gee, Henry; Hardy, William John, eds. (1914). Documents Illustrative of English Church History. London: Macmillan.

- ↑ "Marian Government Policies". Retrieved 5 July 2007.

- ↑ "Pole, Reginald (PL556R)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ↑ Cross, F. L.; Livingstone, E. A., eds. (1997). The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (3rd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 428. ISBN 019211655X.

- ↑ "Thomas Cranmer". Stpeter.org. Retrieved 5 December 2011.

- ↑ Pogson, Rex H. (1975). "Reginald Pole and the Priorities of Government in Mary Tudor's Church". The Historical Journal. 18 (1): 3–20. doi:10.1017/S0018246X00008645.

- 1 2 Schama, Simon (2003) [2000]. "Burning Convictions". A History of Britain 1: At the Edge of the World?. London: BBC Worldwide. pp. 272–273. ISBN 0-563-48714-3.

- ↑ Churchill, Winston (1958). A History of the English-Speaking Peoples.

- 1 2 Churchill, Winston (1966). The New World. Dodd, Mead. p. 99.

- ↑ p. 24 May 9 History Today, an excerpted article taken from Eamon Duffy's "Fires of Faith: Catholic England under Mary Tudor," published by Yale University Press- History Today Vol 59 (5) May 2009, pp 24–29

- ↑ five volumes, Brescia, 1744–57

- ↑ Dwyer, p. xxiii

- ↑ "Archives Hub". Archives Hub. Retrieved 5 December 2011.

Sources

- T. Phillips, History of the Life of Reginald Pole (two volumes, Oxford, 1764), the earliest English.

- A. M. Stewart, Life of Cardinal Pole (London, 1882)

- F. G. Lee, Reginald Pole, Cardinal Archbishop of Canterbury: An Historical Sketch (London, 1888)

- Athanasius Zimmermann, Kardinal Pole: sein Leben und seine Schriften (Regensberg, 1893)

- James Gairdner, The English Church in the Sixteenth Century (London, 1903)

- Martin Haile, Life of Reginald Pole (New York, 1910)

- Dermot Fenlon, Heresy and Obedience in Tridentine Italy: Cardinal Pole and the Counter Reformation, Cambridge University Press, 2008.

- Fray Bartolome Carranza Y El Cardenal Pole: Un Navarro En La Restauracion Catolica De Inglaterra (1554–1558) by Jose Ignacio Tellechea Idigoras. ISBN 84-235-0066-7 . Hardcover, Diputacion Foral de Navarra, Institucion Principe de Viana, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cientificas. 1977.

- Attribution

-

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Gilman, D. C.; Thurston, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). "Pole, Reginald". New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Gilman, D. C.; Thurston, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). "Pole, Reginald". New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.  This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Thurston, Herbert (1911). "Reginald Pole". In Herbermann, Charles. Catholic Encyclopedia. 12. New York: Robert Appleton.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Thurston, Herbert (1911). "Reginald Pole". In Herbermann, Charles. Catholic Encyclopedia. 12. New York: Robert Appleton.

External links

- "The role of the Venetian Oligarchy" by Webster Tarpley (includes detailed discussion of Pole's activities in Italy)

- "Queen Mary" by Alfred Tennyson, "Enter Cardinal Pole"

- Henry Cole, Cardinal Pole's Vicar General, tries to restore Catholicism at Cambridge University

- Works by or about Reginald Pole in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- T. F. Mayer, 'Pole, Reginald (1500–1558)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2008, Reginald Pole.

| Religious titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Thomas Cranmer |

Archbishop of Canterbury 1556–1558 |

Succeeded by Matthew Parker |

| Academic offices | ||

| Preceded by John Mason |

Chancellor of the University of Oxford 1556–1558 |

Succeeded by The Earl of Arundel |

| Preceded by Stephen Gardiner |

Chancellor of the University of Cambridge 1556–1558 |

Succeeded by Lord Burghley |