Randolph Churchill

| The Right Honourable Randolph Churchill MBE | |

|---|---|

| |

| Member of Parliament for Preston | |

|

In office 29 September 1940 – 5 July 1945 Serving with Edward Cobb | |

| Preceded by | Adrian Moreing |

| Succeeded by | John William Sunderland |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Randolph Frederick Edward Spencer-Churchill May 28, 1911 London, England, UK |

| Died |

June 6, 1968 (aged 57) East Bergholt, Suffolk, England, UK |

| Nationality | British |

| Political party | Conservative |

| Spouse(s) |

Pamela Digby (m. 1939; div. 1946) June Osborne (m. 1948; his death 1968) |

| Children |

Winston Arabella |

| Education | Eton College |

| Alma mater | Christ Church |

| Profession | Journalist, soldier |

| Religion | Anglicanism |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch | British Army |

| Years of service | 1940–1945 |

| Rank | Lieutenant |

| Unit | 4th Queen's Own Hussars |

| Battles/wars | World War II |

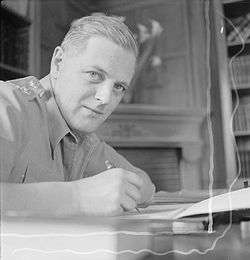

Randolph Frederick Edward Spencer-Churchill MBE (28 May 1911 – 6 June 1968) was a journalist and a Conservative Member of Parliament (MP) for Preston from 1940-45.

He was the son of British Prime Minister Sir Winston Churchill and his wife Clementine. He wrote the first two volumes of the official life of his father, complemented by an extensive archive of materials. His first wife (1939–46) was Pamela Digby; their son, Winston, followed his father into Parliament.

Early life and family

Randolph was educated at Eton College and Christ Church, Oxford and became a journalist. In 1931 he shared Edward James's house in London with John Betjeman. While attending Oxford, Churchill became embroiled in the controversy of February 1933 King and Country debate.

Three weeks after the associated pacifist resolution was passed, Churchill proposed a resolution at the Oxford Union to delete the "King and Country" motion from the Union's records but this was defeated by 750 votes to 138 in a rowdy debate (one which was better attended than the original debate), where Churchill was met by a barrage of hisses and stink bombs. A bodyguard of Oxford Conservatives and police escorted Churchill back to his hotel after the debate.[1][2]

He was married twice. His first marriage, to socialite Pamela Digby produced a son, Winston, who became a Member of Parliament. The marriage ended in divorce in 1945. His second marriage to June Osborne produced a daughter, Arabella Churchill. For the last twenty years of his life, he reportedly conducted an affair with Natalie Bevan, the wife of Bobby Bevan.[3]

Early political career

Randolph Churchill's political career (like that of his son) was not as successful as that of his father or grandfather Lord Randolph Churchill. In an attempt to assert his own political standing he announced in January 1935 that he was a candidate in the Wavertree by-election in Liverpool; on 6 February 1935, an Independent Conservative on a platform of rearmament and Anti-Indian Home Rule. His involvement was criticised by his father for splitting the official Conservative vote and letting in a winning Labour candidate, although Winston appeared to support Randolph on the hustings.[4]

Early in the campaign in March 1935, he sponsored an Independent Conservative candidate, Richard Findlay, also a member of the British Union of Fascists, to stand in a by-election in Norwood. This attracted no backing from MPs or the press and Findlay lost[5] to the official Conservative candidate, Duncan Sandys, who later that same year, in September, became Randolph's brother-in-law, marrying his sister Diana.[6]

Having blamed Baldwin and the party organization for his loss, he libeled Sir Thomas White. Over the summer he was summoned to the High Court to pay damages of £1,000; but immediately back-tracked, when advised that without an apology a career in politics was over, avoiding "a reaction hereafter."[7]

Randolph Churchill was an effective manipulator of the media, the Daily Mail among the powerful press titles which, sidelined by the popularity contest, bowed to the superior pull of the Churchill name. In the 1935 general election he stood as the official Conservative candidate at Labour-held West Toxteth; reportedly he was so unwelcome they threw bananas.[8] Lord Derby lent his support, and Randolph continued to aid the Conservative campaigning across the city.[9] He also stood as a Unionist on 10 February 1936 in a bye-election at Ross and Cromarty opposed to the National Government candidacy of Malcolm MacDonald but was defeated again.[10]

Military service: Second World War

Randolph Churchill served with his father’s old regiment, the 4th Queen's Own Hussars.[11] He was one of the oldest of the junior officers, and not popular with his peers. In order to win a bet, he walked the 106-mile round trip from their base in Hull to York and back in under 24 hours. He was followed by a car, both to witness the event and in case his blisters became too painful to walk further, and made it with around twenty minutes to spare. To his great annoyance, his brother officers did not pay up.[12]

In 1940 Randolph's father, to whom he remained close both politically and socially, became Prime Minister, shortly before the Battle of Britain. Captain Lord Louis Mountbatten was dispatched, along with Lieutenant Randolph Churchill in tow, aboard HMS Kelly to Cherbourg to evacuate the Duke and Duchess of Windsor. Randolph was on board the destroyer untidily attired in his 4th Hussars uniform; he had forgotten to attach the spurs correctly to his boots. The Duke was mildly shocked by Churchill's "appearance... rendered less martial." HMS Kelly operated from the Plymouth dockyard for the duration of the anti-submarine warfare during the Battle of Britain.[13]

Randolph was elected unopposed to Parliament for Preston at a wartime by-election in September 1940. He was then posted to the Western Desert theatre, where he was promoted to the rank of Major and for a time edited a newspaper Desert News for the troops.[14] He was also attached for a time to the newly formed Special Air Service (SAS), joining their CO, David Stirling and six SAS men, on a mission behind enemy lines in the Libyan Desert to Benghazi.[15][lower-alpha 1]

On leave, he criticised Tories for exculpating Winston Churchill's decision to defend Greece and Crete. He was sensitive to the "co-operation and self-sacrifice" of parts of the Empire that in 1942 were in more immediate danger than the British Isles, mentioning Australia and Malaya which suffered under Japanese threats of invasion. He was scathing of Sir Herbert Williams' Official Report into the Conduct of the War.[16]

In 1942 he visited Morocco in time to witness the American and Free French invasion. At the same time the outspoken press baron Lord Beaverbrook, assiduously befriended by the Prime Minister, was in hot pursuit of Randolph's wife, Pamela. There were rumours that they were suffering a rocky patch in their marriage but Randolph continued to be jealous of the brash, outspoken Canadian's access to powerful positions.[17] Randolph encouraged the conversion of Vichy fighters to de Gaulle's army, submitting reports to Parliament on 23 February 1943.[18]

Churchill also went on a military and diplomatic mission to Yugoslavia in 1944, part of the British support for the Partisans during that civil war. Evelyn Waugh accompanying Churchill arrived on the island of Vis on 10 July, where they met Tito, who had barely managed to evade the Germans after their "Operation Knight's Leap" (Rosselsprung) airdrop outside Tito's Drvar headquarters.[19] In both the Western Desert Campaign and Yugoslavia, Churchill crossed paths with Fitzroy Maclean, who wrote of their adventures together, and some of the problems Churchill caused him, in his memoir Eastern Approaches. He was ordered by Maclean to take charge of the military mission in Croatia.[20] With Waugh he established a military mission at Topusko on 16 September 1944.[21] One outcome was a formidable report detailing Tito's persecution of the clergy. It was "buried" by Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden (who also attempted to discredit Waugh) to save diplomatic embarrassment, as Tito was then seen as a required ally of Britain and an official "friend".[22][23][24]

Later political career

Randolph's attendance in the Commons was irregular and patchy, which may have contributed to his defeat in 1945. Frustrated and bored by a lack of success, Randolph had to watch his father's triumphal reception through the country. At a dinner at Claridges with Brendan Bracken and Winston on 31 August, he snapped, got drunk and went into an angry rant.[25] Many thought Bracken and Beaverbrook the architects of the general election defeat reported on 26 July 1945.[26]

In his last two attempts to return to parliament, he lost to future Labour leader Michael Foot at Plymouth Devonport in the 1950[27] and 1951 general elections.[28] During the post-war era Anthony Eden remained the Prime Minister's designated successor, yet when Eden married Clarissa Churchill in 1952, Randolph could hardly contain his utter contempt for his cousin's new husband. He had known Eden all his life, dubbing his ranting phone calls the "Eden Terror". Many commentators at the time and since have considered Eden unsuited for leadership of the party.[29]

Winston declined a peerage at the end of the Second World War, and then again on his retirement in 1955 (when he was offered the Dukedom of London),[30] ostensibly so as not to compromise his son's political career by preventing him from serving in the House of Commons (life peerages, titles not inherited by sons, were not created until 1958). The main reason was actually that Winston himself wanted to remain in the Commons[31]— but by 1955, when his father resigned as Prime Minister, Randolph's political career was "already hopeless".[31] This occasion was sufficient to justify another barrage of attacks in the press on Eden later in the year. The renewed criticisms included "a lack of firm government" by the Prime Minister, against a backdrop of a credit squeeze and striking unions. The disastrous Suez Crisis appeared to vindicate Randolph's long-held doubts about Eden.[32]

Social reputation

Randolph, spoiled by his father, began drinking heavily in his late teens, under the influence of Lord Birkenhead.[33] Thereafter he had a lifelong reputation for a serious drinking problem and for rude, boorish behaviour.[34] Evelyn Waugh, who restored friendly relations with Randolph in the spring of 1964 after years of enmity, nonetheless could not resist a jibe later that year. On hearing that a recently removed lung growth was not malignant, Waugh said "It was a typical triumph of modern science to find the one part of Randolph which was not malignant and to remove it." [35]

Literary activities

Randolph inherited something of his father's literary flair, carving out a career for himself as a journalist. He edited the "Londoner's Diary" in the Evening Standard and was one of the best-paid gossip columnists on Fleet Street. He edited collections of his father's speeches, which were published in seven books between 1938 and 1961.[27]

In 1964 Churchill published The Fight For The Party Leadership ... describing the Conservatives' destructive internal struggle in the wake of Macmillan's resignation (Randolph had supported Lord Hailsham in the contest). The former Cabinet minister Iain Macleod wrote a review in The Spectator strongly critical of Randolph's book, and alleging that Macmillan had manipulated the process of "soundings" to ensure that his deputy Rab Butler was not chosen as his successor.[36]

He wrote a memoir of his early life, Twenty-One Years, published in 1965.[27] The following year he started an official biography of his father, but had finished only the second volume by the time of his death in 1968. It was completed by Sir Martin Gilbert.[lower-alpha 2]

He had signed a contract with the American politician Robert Kennedy to write a biography of his elder brother, President John F. Kennedy, who had been assassinated in 1963. As a consequence, Randolph obtained access to the Kennedy archives, but he died before beginning work, the very same day that Robert was assassinated.[37]

Death

Randolph Churchill died on 6 June 1968 at his home, Stour House, East Bergholt, Suffolk,[38] of a heart attack, aged 57. He is buried with his parents (his mother outliving him by almost a decade) and siblings at St Martin's Church at Bladon near Woodstock, Oxfordshire.[39]

Fictional role

H.G. Wells in The Shape of Things to Come, published in 1934, predicted a Second World War in which Britain would not participate but would vainly try to effect a peaceful compromise. In this vision, Randolph was mentioned as one of several prominent Britons delivering "brilliant pacifist speeches [which] echo throughout Europe", but fail to end the war.[40]

A more factual account was ITV TV docudrama Churchill's Secret, a screenplay based on the book The Churchill Secret: KBO by Jonathan Smith. Broadcast in 2016, it starred Michael Gambon, and depicted Winston Churchill during the summer of 1953 when he suffered a severe stroke, precipitating therapy and resignation; the character of Randolph (in a brief appearance) was played by the English actor Matthew Macfadyen.

Works

- Arms and The Covenant (1938)

- Into Battle (1940)

- The Sinews of Peace (1948)

- European Union (1950)

- In the Balance (1951)

- Stemming the Tide (1953)

- They Serve The Queen (1953)

- The Story of the Coronation (1953)

- Fifteen Famous English Homes (1954)

- What I Said About the Press (1957)

- The Rise and Fall of Sir Anthony Eden (1959)

- Lord Derby: King of Lancashire (1960)

- The Unwritten Alliance (1961)

- The Fight for the Tory Leadership (1964)

- Twenty-One Years (1965)

- Winston S. Churchill: Volume One: Youth, 1874–1900 (1966)

- Winston S. Churchill: Volume One Companion, 1874–1900 (1966, in two parts)

- Winston S. Churchill: Volume Two: Young Statesman, 1901–1914 (1967)

- Winston S. Churchill: Volume Two Companion, 1900–1914 (1969, in three parts; published posthumously with the assistance of Martin Gilbert, who wrote future volumes of the biography)

- The Six Day War (1967; co-authored with his own son, Winston S. Churchill)

See also

Notes

- ↑ although the enlisted ranks of the SAS were made up of picked men from elite regiments, many of the officers were appointed on the basis of social connections, e.g. membership of White’s Club. The same was true of the Royal Marine Commandos, in which Churchill’s colleague Evelyn Waugh served.

- ↑ before receiving a knighthood Martin Gilbert was named as "Churchill's Official Biographer".

References

- ↑ Derek Round and Kenelm Digby (2002). Barbed Wire Between Us: A Story of Love and War. Random House, Auckland.

- ↑ Jan Morris, The Oxford Book of Oxford (Oxford University Press, 2002), p. 275.

- ↑ Anita Leslie. Cousin Randolph – Life of Randolph Churchill (1985); see also Jonathan Aitken. Heroes and Contemporaries. 2006, pp. 36–37.

- ↑ Gilbert, Martin (1981). Winston Churchill, The Wilderness Years. Macmillan. pp. 123–24. ISBN 0-333-32564-8.

- ↑ Winston Churchill, The Wilderness Years. p. 124.

- ↑ Clark, Tories, p. 542

- ↑ 16 July 1935, from a solicitor's letter to Winston Churchill, CHAR 2/246/108, CUCC

- ↑ CHAR 2/246/161 - CUCC, chu.cam.ac.uk; accessed 27 August 2016.

- ↑ AR 2/246/116, Letter from Lord Derby to WSC, offering to help Randolph Churchill's election campaign in Liverpool West Toxteth. 23 Oct 1935 CHAR 2/246/117

- ↑ Profile, leighrayment.com; accessed 12 March 2016.

- ↑ Churchill 1997, p. 168

- ↑ Churchill 1997, p. 176

- ↑ P. Zeigler, Mountbatten, p. 125

- ↑ Churchill 1997, pp. 196–97

- ↑ Churchill 1997, pp. 207–15

- ↑ HC Deb 28 January 1942 vol. 377, cc. 727–890

- ↑ A.Clark, Tories, pp. 229, 232

- ↑ North Africa, HC Deb 16 March 1943 vol. 387, cc 1033–37

- ↑ Churchill 1997, p. 251

- ↑ Churchill 1997, p. 252

- ↑ Churchill 1997, p. 256

- ↑ Hastings 1994, pp. 268–91

- ↑ Stannard 1994, pp. 138–48

- ↑ Sykes 1975, p. 273

- ↑ Jenkins, p. 804

- ↑ Jenkins, p. 797

- 1 2 3 Who Was Who, 1961–1970. A and C Black. 1972. p. 205. ISBN 0-7136-1202-9.

- ↑ UK general election results, 1951, psr.keele.ac.uk; accessed 6 February 2015.

- ↑ Thorpe, Eden, p. 379

- ↑ Rasor, Eugene L. Winston S. Churchill, 1874-1965: a comprehensive historiography and annotated bibliography, p. 205. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2000; ISBN 978-0-313-30546-7.

- 1 2 R. Jenkins, Churchill (2001), p. 896

- ↑ Ramsden, apetite, pp. 332–33

- ↑ Jenkins 2001, p. 356

- ↑ Lovell 2012, pp. 381, 405, 432, 439, 448, 473–74, 492, 496, 506–08, 519, 523, 526, 574

- ↑ Lovell 2012, p. 536

- ↑ J.Harris, Conservatives, p. 504

- ↑ "Grandson to Finish Work On Churchill", The New York Times, p. 50; 12 June 1968; retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ↑ Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Volume 11. Oxford University Press. 2014. p. 638. ISBN 0-19-861361-X.Article by Robert Blake.

- ↑ "Bladon (Saint Martin) Churchyard. Randolph Frederick Edward Spencer Churchill". BillionGraves. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- ↑ The Shape of Things to Come references, telelib.com; accessed 3 July 2014.

Primary sources

- TNA CAB 120/808, (March 1942 – May 1945)

- TNA FO 198/860, (1944)

- TNA HO 252/136, (1961–1962)

- CUCC HNKY 24/15, (1958)

- TNA FO 271/156315, (1961)

- Churchill, Winston (1997). His Father’s Son: The Life of Randolph Churchill. London: Orion. ISBN 978-1-857999693.

- Leslie, Anita (1985). Cousin Randolph–Life of Randolph Churchill.

- Aitken, Jonathan (2006). Heroes and Contemporaries.

- Glossary

- TNA - The National Archives, Kew

- CAB - British Cabinet Papers

- FO - British Foreign Office Papers

- HO - British Home Office Papers

- CUCC - Cambridge University Churchill Archive Centre

- HNKY - Collection of Maurice, Lord Hankey

Secondary sources

- Clark, Alan (1998). The Tories: Conservatives and the Nation State 1922–1997. London. ISBN 0-297-81849-X.

- Davie, Michael, ed. (1982) [entries for March through September, 1944]. The Diaries of Evelyn Waugh. Penguin.

- Harris, Robin (2011). The Conservatives: A History. London. ISBN 978-0-593-06511-2.

- Hastings, Selina (1994). Evelyn Waugh: A biography. London: Sinclair-Stevenson. ISBN 1-85619-223-7.

- Heath, Edward (1998). The Course of My Life. London: Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 978-0340708521.

- Jenkins, Roy (2001). Churchill: A Biography. ISBN 978-0-374-12354-3.

- Lovell, Mary S. (5 April 2012). The Churchills: A Family at the Heart of History — from the Duke of Marlborough to Winston Churchill. Abacus. ISBN 978-0349119786.

- Ogden, Christopher (1994). Life Of The Party: Biography of Pamela Digby Churchill. Little Brown & Company.

- Ramsden, John (1997). An apetite for Power: A History of the Conservative Party. London.

- Roberts, Andrew (2004) [1994]. Eminent Churchillians. London.

- Seldon, Anthony (1981). Churchill's Indian Summer: The Conservative Government, 1951–55. London.

- Stannard, Martin (1994). Evelyn Waugh: The Later Years, 1939–1966. London: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393311662.

- Sykes, Christopher (1975). Evelyn Waugh – a Biography. London: Collins.

- Zeigler, Philip (1985). Mountbatten. London. ISBN 0-00-637047-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Randolph Churchill. |

- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by Randolph Churchill

| Parliament of the United Kingdom | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Edward Cobb and Adrian Moreing |

Member of Parliament for Preston 1940–1945 With: Edward Cobb |

Succeeded by Samuel Segal and John Sunderland |