Ram Mohan Roy

| Raja Ram Mohan Roy | |

|---|---|

|

Raja Ram Mohan Roy is regarded as the Father of the Indian Renaissance | |

| Native name | রামমোহন রায় |

| Born |

22 May 1772 Radhanagar, Bengal Presidency, British India |

| Died |

27 September 1833 (aged 61) Stapleton, Bristol, England |

| Cause of death | Meningitis |

| Nationality | British Indian |

| Other names | Herald Of New Age |

| Known for |

Bengal Renaissance, Brahmo Sabha (socio, political reforms) |

| Title | Raja |

| Successor | Dwarkanath Tagore |

| Religion | Hinduism |

| Parent(s) | Ramakant Roy & Tarini Devi |

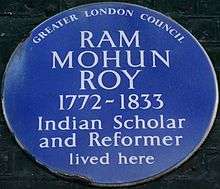

Raja Ram Mohan Roy (Bengali: রামমোহন রায়; 22 May 1772 – 27 September 1833) was the founder of the Brahmo Sabha[1] movement in 1828, which engendered the Brahmo Samaj, an influential socio-religious reform movement. His influence was apparent in the fields of politics, public administration and education as well as religion. He was known for his efforts to establish the abolishment of the practice of sati, the Hindu funeral practice in which the widow was compelled to sacrifice herself in her husband’s funeral pyre in some parts of Bengal. What is not so well known is that Roy protested against the East India Company's decision to support vernacular education and insisted that English replace Sanskrit and Persian in India. It was he who first introduced the word "Hinduism" into the English language in 1816. For his diverse activities and contributions to society, Raja Ram Mohan Roy is regarded as one of the most important and contentious figures in the Bengali renaissance. His efforts to protect Hinduism and Indian rights and his closeness with the British government earned him the title "The Father of the Indian Renaissance".

Early life and education (1772–1796)

Ram Mohan Roy was born in Radhanagar, Arambagh subdivision, Hooghly District, Bengal Presidency, in 1772, into the Rarhi Brahmin caste.[2] His father Ramkanta was a Vaishnavite, while his mother Tarinidevi was from a Shivaite family. This was unusual - Vaishnavite did not marry commonly Shivaite at the times.

- Thus one parent prepared him for the occupation of a scholar, the sastrin, the other secured for him all the worldly advantage needed to launch a career in the laukik or worldly sphere of public administration. Torn between these two parental ideals from early childhood, Ram Mohan vacillated the rest of his life, moving from one to the other and back.[3]

Ram Mohan Roy was married three times, which fell in the strict framework of his polygamous and caste customs. His first wife died early in his childhood. He conceived two sons, Radhaprasad in 1800 and Ramaprasad in 1812 with his second wife, who died in 1824. Roy's third wife outlived him.

Ram Mohan Roy's early education was controversial. The common version is "Ram Mohan started his formal education in the village pathshala where he learned Bengali and some Sanskrit and Persian. Later he is said to have studied Persian and Arabic in a madrasa in Patna and after that he was sent to Benares (Kashi) for learning the intricacies of Sanskrit and Hindu scripture, including the Vedas and Upanishads. The dates of his sojourn in both these places is uncertain. However, the commonly held belief is that he was sent to Patna when he was nine years old and two years later to Benares."[3]

Impact

Ram Mohan Roy's impact on modern Indian history was a revival of the pure and ethical principles of the Vedanta school of philosophy as found in the Upanishads. He preached the unity of God, made early translations of Vedic scriptures into English, co-founded the Calcutta Unitarian Society and founded the Brahma Samaj. The Brahma Samaj played a major role in reforming and modernising the Indian society. He successfully campaigned against sati, the practice of burning widows. He sought to integrate Western culture with the best features of his own country's traditions. He established a number of schools to popularize a modern system (effectively replacing Sanskrit based education with English based education) of education in India. He promoted a rational, ethical, non-authoritarian, this-worldly, and social-reform Hinduism. His writings also sparked interest among British and American Unitarians.

Christianity and the early rule of the East India Company (1795–1828)

During these overlapping periods, Ram Mohan Roy acted as a political agitator and agent, representing Christian missionaries[4] whilst employed by the East India Company and simultaneously pursuing his vocation as a Pandit. To understand fully this complex period in his life leading up to his eventual Brahmoism needs reference to his peers.

In 1792, the British Baptist shoemaker William Carey published his influential missionary tract, An Enquiry of the obligations of Christians to use means for the conversion of heathens.[5]

In 1793, William Carey landed in India to settle. His objective was to translate, publish and distribute the Bible in Indian languages and propagate Christianity to the Indian peoples.[6] He realized the "mobile" (i.e. service classes) Brahmins and Pundits were most able to help him in this endeavor, and he began gathering them. He learnt the Buddhist and Jain religious works to better argue the case for Christianity in the cultural context.

In 1795, Carey made contact with a Sanskrit scholar, the Tantric Hariharananda Vidyabagish,[7] who later introduced him to Ram Mohan Roy, who wished to learn English.

Between 1796 and 1797, the trio of Carey, Vidyavagish and Roy fabricated a spurious religious work known as the "Maha Nirvana Tantra" (or "Book of the Great Liberation")[8] and passed it off as an ancient religious text to "the One True God", actually the Holy Spirit of Christianity masquerading as Brahma. Carey's involvement is not recorded in his very detailed records and he reports only learning to read Sanskrit in 1796 and only completed a grammar in 1797, the same year he translated part of The Bible from Joshua to Job, a massive task.[9] (The explanation later given by Ram Mohan Roy to his family concerning his whereabouts during this period is that he went to "Tibet", then as far away as "Timbuktoo"). For the next two decades this document was regularly augmented.[10] Its judicial sections were used in the law courts of the English Settlement in Bengal as Hindu Law for adjudicating upon property disputes of the zamindari. However, a few British magistrates and collectors began to suspect it as a forgery and its usage (as well as the reliance on pundits as sources of Hindu Law) was quickly deprecated. Vidyavagish had a brief falling out with Carey and separated from the group, but maintained ties to Ram Mohan Roy.[11] (The Maha Nirvana Tantra's significance for Brahmoism lay in the wealth that accumulated to Ram Mohan Roy and Dwarkanath Tagore by its judicial use, and not due to any religious wisdom within, although it does contain an entire chapter devoted to "the One True God" and his worship.)

In 1797, Ram Mohan reached Calcutta and became a "banian" (moneylender), mainly to impoverished Englishmen of the Company living beyond their means. Ram Mohan also continued his vocation as pundit in the English courts and started to make a living for himself. He began learning Greek and Latin.

In 1799, Carey was joined by missionary Joshua Marshman and the printer William Ward at the Danish settlement of Serampore.

From 1803 till 1815, Ram Mohan served the East India Company's "Writing Service", commencing as private clerk "munshi" to Thomas Woodroffe, Registrar of the Appellate Court at Murshidabad[12] (whose distant nephew, John Woodroffe — also a Magistrate — and later made a rich living off the spurious Maha Nirvana Tantra under the pseudonym Arthur Avalon).[13] Roy resigned from Woodroffe's service due to allegations of corruption. Later he secured employment with John Digby, a Company collector, and Ram Mohan spent many years at Rangpur and elsewhere with Digby, where he renewed his contacts with Hariharananda. William Carey had by this time settled at Serampore and the old trio renewed their profitable association. William Carey was also aligned now with the English Company, then headquartered at Fort William, and his religious and political ambitions were increasingly intertwined.[14]

The East India Company was draining money from India at a rate of three million pounds a year in 1838. Ram Mohan Roy was one of the first to try to estimate how much money was being driven out of India and to where it was disappearing. He estimated that around one-half of all total revenue collected in India was sent out to England, leaving India, with a considerably larger population, to use the remaining money to maintain social wellbeing.[15] Ram Mohan Roy saw this and believed that the unrestricted settlement of Europeans in India governing under free trade would help ease the economic drain crisis.[16]

At the turn of the 19th century, the Muslims, although considerably vanquished after the battles of Plassey and Buxar, still posed a formidable political threat to the Company. Ram Mohan was now chosen by Carey to be the agitator among them.[17]

Under Carey's secret tutelage in the next two decades, Ram Mohan launched his attack against the bastions of Hinduism of Bengal, namely his own Kulin Brahmin priestly clan (then in control of the many temples of Bengal) and their priestly excesses.[10] The social and theological issues Carey chose for Ram Mohan were calculated to weaken the hold of the dominant Kulin class (especially their younger disinherited sons forced into service who constituted the mobile gentry or "bhadralok" of Bengal) from the Mughal zamindari system and align them to their new overlords of Company. The Kulin excesses targeted include sati (the concremation of widows), polygamy, idolatory, child marriage and dowry. All causes were equally dear to Carey's ideals.

Roy's contemporary biographer records:

- "In 1805 Rammohun published Tuhfat-ul-Muwahhidin (A Gift to Monotheists) — an essay written in Persian with an introduction in Arabic in which he rationalised the unity of God. Being published in Persian, it antagonised sections of the Muslim community and for the next decade Rammohun travelled to serve with John Digby of the East India Company as munshi and then as Diwan. His English and knowledge of England's Baptist Christianity increased tremendously. He also cultivated friendship in a Jain community to better understand their approach to Hinduism, rejecting priesthood — which for long in Bengal demanded bloody ritual sacrifices — and God itself.

- "In 1815 after amassing large wealth, enough to leave the Company, Rammohun resettled in Calcutta and started an Atmiya Sabha, as a philosophical discussion circle to debate monotheistic Hindu Vedantism and like subjects. Rammohun's mother, however, had not forgiven him and ironically from 1817 a series of lawsuits were filed accusing Rammohun of apostasy with the object of severing him from the family zamindari. Rammohun countered denouncing his family's practice of sati[18] where widows were burned on their husband's pyres so that they laid no claim to property via the British courts. 1817 was also the year when Rammohun was alienated from Hindu zamindars in an incident concerning the Hindu (later Presidency) College involving David Hare. Hindu public outrage in 1819 also followed Rammohun's triumph in a public debate over idolatry with Subramanya Shastri, a Tamil Brahmin. The victory, however, also exposed chinks in Rammohun's command over Brahmanical scripture and Vedanta whose study he had somewhat neglected. The trusted younger brother of Hariharanda, a Brahmin of great intellect Ram Chunder Vidyabagish was brought in to repair the breech and would be increasingly identified as Rammohun's alter-ego in matters theological for the rest of Rammohun's life especially in matters of Bengali concern and language. By now it was suspected (but never established) that Carey and Marshman were behind Rammohun's English works, a charge repeatedly made by the Hindu zamindars. From time to time Dwarkanath Tagore a young Hindu Zamindar had been attending Sabha meetings and he privately persuaded Rammohun (financially reduced by lawsuits and in constant danger from Hindu assassins) to disband the Atmiya Sabha in 1819 and instead be political agent for him."

- From 1819, Rammohun's battery increasingly turned against Carey and the Serampore missionaries. With Dwarkanath's munificence he launched a series of attacks against Baptist "Trinitarian" Christianity and was now considerably assisted in his theological debates by the Unitarian faction of Christianity." [19]

Middle "Brahmo" period (1820–1830)

This was Ram Mohan's most controversial period. Commenting on his published works Sivanath Sastri writes:[20]

"The period between 1820 and 1830 was also eventful from a literary point of view, as will be manifest from the following list of his publications during that period:

- Second Appeal to the Christian Public, Brahmanical Magazine - Parts I, II and III, with Bengali translation and a new Bengali newspaper called Sambad Kaumudi in 1821;

- A Persian paper called Mirat-ul-Akbar contained a tract entitled Brief Remarks on Ancient Female Rights and a book in Bengali called Answers to Four Questions in 1822;

- Third and final appeal to the Christian public, a memorial to the King of England on the subject of the liberty of the press, Ramdoss papers relating to Christian controversy, Brahmanical Magazine, No. IV, letter to Lord Arnherst on the subject of English education, a tract called "Humble Suggestions" and a book in Bengali called "Pathyapradan or Medicine for the Sick," all in 1823;

- A letter to Rev. H. Ware on the " Prospects of Christianity in India" and an "Appeal for famine-smitten natives in Southern India" in 1824;

- A tract on the different modes of worship, in 1825;

- A Bengali tract on the qualifications of a God loving householder, a tract in Bengali on a controversy with a Kayastha, and a Grammar of the Bengali language in English, in 1826;

- A Sanskrit tract on "Divine worship by Gayatri" with an English translation of the same, the edition of a Sanskrit treatise against caste, and the previously noticed tract called "Answer of a Hindu to the question &c.," in 1827;

- A form of Divine worship and a collection of hymns composed by him and his friends, in 1828;

- "Religious Instructions founded on Sacred Authorities" in English and Sanskrit, a Bengali tract called "Anusthan," and a petition against Suttee, in 1829;

- A Bengali tract, a grammar of the Bengali language in Bengali, the Trust Deed of the Brahmo Samaj, an address to Lord William Bentinck, congratulating him for the abolition of sati, an abstract in English of the arguments regarding the burning of widows, and a tract in English on the disposal of ancestral property by Hindus, in 1830."

Life in England (1831–1833)

He publicly declared that he would emigrate from British empire if parliament failed to pass the Reform Bill.

In 1830, Ram Mohan Roy travelled to the United Kingdom as an ambassador of the Mughal Empire, to ensure that Lord William Bentinck's Bengal Sati Regulation, 1829 banning the practice of Sati was not overturned. He also visited France.

He died at Stapleton, then a village to the north east of Bristol (now a suburb), on the 27th September 1833 of meningitis and was buried in Arnos Vale Cemetery in southern Bristol.

Religious reforms

The religious reforms of Roy contained in some beliefs of the Brahmo Samaj expounded by Rajnarayan Basu[21] are:-

- Brahmo Samaj believe that the fundamental doctrines of Brahmoism are at the basis of every religion followed by man.

- Brahmo Samaj believe in the existence of One Supreme God — "a God, endowed with a distinct personality & moral attributes equal to His nature, and intelligence befitting the Author and Preserver of the Universe," and worship Him alone.

- Brahmo Samaj believe that worship of Him needs no fixed place or time. "We can adore Him at any time and at any place, provided that time and that place are calculated to compose and direct the mind towards Him."

Social reforms

- Crusaded against social evils like sati, polygamy and child marriage.

- Demanded property inheritance rights for women.

- In 1828, he set up the Brahmo Sabha a movement of reformist Bengali Brahmins to fight against social evils.

Roy’s political background fit influenced his social and religious to reforms of Hinduism. He writes,

"The present system of Hindus is not well calculated to promote their political interests…. It is necessary that some change should take place in their religion, at least for the sake of their political advantage and social comfort."[22]

Ram Mohan Roy’s experience working with the British government taught him that Hindu traditions were often not credible or respected by western standards and this no doubt affected his religious reforms. He wanted to legitimize Hindu traditions to his European acquaintances by proving that "superstitious practices which deform the Hindu religion have nothing to do with the pure spirit of its dictates!"[23] The "superstitious practices" Ram Mohan Roy objected included sati, caste rigidity, polygamy and child marriages.[24] These practices were often the reasons British officials claimed moral superiority over the Indian nation. Ram Mohan Roy’s ideas of religion actively sought to create a fair and just society by implementing humanitarian practices similar to Christian ideals and thus legitimize Hinduism in the modern world.

Educationist

- Roy believed education to be an implement for social reform.

- In 1817, in collaboration with David Hare, he set up the Hindu College at Calcutta.

- In 1822, Roy founded the Anglo-Hindu school, followed four years later (1826) by the Vedanta College; where he insisted that his teachingings of monotheistic doctrines be incorporated with "modern, western curriculum.".[25]

- In 1830, he helped Rev. Alexander Duff in establishing the General Assembly's Institution (now known as Scottish Church College), by providing him the venue vacated by Brahma Sabha and getting the first batch of students.

- He supported induction of western learning into Indian education.

- He also set up the Vedanta College, offering courses as a synthesis of Western and Indian learning.

Journalist

- Roy published journals in English, Hindi, Persian and Bengali.

- His most popular journal was the Sambad Kaumudi. It covered topics like freedom of press, induction of Indians into high ranks of service, and separation of the executive and judiciary.

- When the English Company muzzled the press, Ram Mohan composed two memorials against this in 1829 and 1830 respectively.

Mausoleum at Arnos Vale

Ram Mohan Roy was originally buried on 18 October 1833, in the grounds of Stapleton Grove where he had died of meningitis on 27 September 1833. Nine and a half years later he was reburied on 29 May 1843 in a grave at the new Arnos Vale Cemetery, in Brislington, East Bristol. A large plot on The Ceremonial Way there, had been bought by William Carr and William Prinsep, and the body in its lac and lead coffin was placed later in a deep brick-built vault, over seven feet underground. Two years after this Dwarkanath Tagore helped pay for the chattri raised above this vault, although there is no record of his ever visiting Bristol. The chattri was designed by the artist William Prinsep, who had known Ram Mohan in Calcutta. The Raja's remains are still there, despite a misleading story first suggested by the Adi Brahmo Samaj Press,[26] and unfortunately repeated later by one (or more) historians, without proper evidence or citation. The coffin has been seen in situ by the Trustee in charge of the 2006/7 repairs to the chattri, which were funded by Aditya Poddar of Singapore.[27][28]

The original brief epitaph,"Rammohun Roy, died Stapleton 27th. Sept. 1833", was suggested by Dwarkanath Tagore, but this plaque was removed to the rear of the tomb by Rev. Rohini Chaterji (sic), who was descended from Radha Prasad Roy. His new and more expansive epitaph was placed at the front. The epitaph reads:

- "A conscientious and steadfast believer in the Unity of Godhead, He consecrated his life with entire devotion to the worship of the divine spirit alone, to great natural talents, he united through mastery of many languages and early distinguished himself as one of the greatest scholars of the day. His unwearied labour to promote the social, moral and physical condition of the people of India, his earnest endeavours to suppress idolatry and the rite of suttee and his constant zealous advocacy of whatever tended to advance the glory of God and the welfare of man live in the grateful remembrance of his countrymen. This tablet records the sorrow and pride with which his memory is cherished by his descendants.

He was born at Radhanagore in Bengal in 1772 and died at Bristol on September 27th 1833."

The Indian High Commission often come to the annual Commemoration of the Raja in September, whilst Bristol's Lord Mayor is always in attendance. The Commemoration is a joint Brahmo-Unitarian service for about 100 people. Brahmo and Unitarian prayers and hymns are sung before the tomb, flowers are laid, and the life of the Raja celebrated in a service.[29] In 2013 a recently discovered ivory bust of Ram Mohan was displayed,[30] in 2014 his original death mask at Edinburgh was filmed and its history discussed.[31]

In September 2008, representatives from the Indian High Commission came to Bristol to mark the 175th anniversary of Ram Mohan Roy's death. During the ceremony Brahmo and Unitarian prayers were recited and songs of Ram Mohan and other Brahmosangeet were performed.[32]

Following on from this visit the Mayor of Kolkata, Bikash Ranjan Bhattacharya (who was amongst the representatives from the India High Commission) decided to raise funds to restore the mausoleum.

Bristol honours Ram Mohan Roy

In 1983, a full scale Exhibition on Ram Mohan Roy was held in Bristol's Museum and Art Gallery. His enormous 1831 portrait by Henry Perronet Briggs still hangs there, and was the subject of a talk by Sir Max Muller in 1873. At Bristol's Centre, on College Green, is a full size bronze statue of the Raja by the modern Kolkata sculptor, Niranjan Pradhan. Another bust by Pradhan, gifted to Bristol by Joyti Basu, sits inside the main foyer of Bristol's City Hall. A pedestrian path at Stapleton has been named "Rajah Rammohun Walk". There is a 1933 Brahmo plaque on the outside west wall of Stapleton Grove, and his first burial place in the garden is marked by railings and a granite memorial stone. His tomb and chattri at Arnos Vale are listed Grade II* by English Heritage, and attract many admiring visitors today.

See also

- Adi Dharm

- Brahmo

- Brahmoism

- Brahmo Samaj

- Hindu School, Kolkata

- Presidency College, Kolkata

- Scottish Church College, Calcutta

References

- ↑ Is Roy the founder of Brahmo Samaj Brahmo Samaj and Raja Ram Mohan Roy

- ↑ Matthew, H. C. G.; Harrison, B. (2004). "The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography". doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/47673.

- 1 2 page 8, Raja Ram Mohan Roy — The Renaissance Man, H.D.Sharma, 2002

- ↑ Biography published in the Atheneum 1834

- ↑ An Enquiry into the Obligations of Christians to Use Means for the Conversion of the Heathens

- ↑ William Carey University

- ↑ Kaumudi Patrika 12 December 1912

- ↑ "Essays in Classical and Modern Hindu Law" John Duncan Derrett

- ↑ "The Life of William Carey (1761-1834) by George Smith (1885) Ch4, p71". Retrieved 2008-12-08.

- 1 2 Syed, M. H. "Raja Rammohan Roy" (PDF). Himalaya Publishing House. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

- ↑ Preface to "Fallacy of the New Dispensation" by Sivanath Sastri, 1895

- ↑ S.D.Collett

- ↑ Mahanirvana Tantra Of The Great ... — Google Books

- ↑ Smith, George. "Life of William Carey". Christian Classics Ethereal Library. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

- ↑ Roy, Rama Dev. Some Aspects of the Economic Drain from India during the British RuleSocial Scientist, Vol. 15, No. 3. March 1987.

- ↑ Bhattacharya, Subbhas. Indigo Planters, Ram Mohan Roy and the 1833 Charter Act Social Scientist, Vol.4, No.3. October 1975.

- ↑ memorial biography in the Atheneum 1834

- ↑ http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/653113/40561

- ↑ Nabble — Origins of Brahmoism — Part 2

- ↑ Sivanath Sastri, History of the Brahmo Samaj, 1911, 1st ed. pg. 44-46

- ↑ http://brahmo.org/brahmo-samaj.html

- ↑ Gauri Shankar Bhatt, "Brahmo Samaj, Arya Samaj, and the Church-Sect Typology" Review of Religions Research. 10. (1968): 24

- ↑ Ram Mohan Roy, Translation of Several Principal Book, Passages, and Text of the Vedas and of Some Controversial works on Brahmunical Theology. (London: Parbury, Allen & Company, 1823) 4.

- ↑ Brahendra N. Bandyopadyay, Rommohan Roy, (London: University Press, 1933) 351.

- ↑ "Ram Mohun Roy." Main. britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/511196/Ram-Mohun-Roy?view=print. 2009.

- ↑ page 129-131.Vol.2 :History of the Adi Brahmo Samaj,1898 (1st edn.) publ. by Adi Brahmo Samaj Press, Calcutta

- ↑ Donation for restoration

- ↑ BBC News — £50k restoration for Indian tomb

- ↑ Celebration at Arnos Vale

- ↑ Ivory bust of Rammohun

- ↑ Documentary on death mask

- ↑ Inauguration of restored mausoleum

Nothing

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ram Mohan Roy. |

- Biography (Calcuttaweb.com)

- Social, Political, Economic, and Educational Ideas of Raja Rammohun Roy

- Biography (Brahmo Samaj)