Ralph Flanders

| Ralph Edward Flanders | |

|---|---|

| |

| United States Senator from Vermont | |

|

In office November 1, 1946 – January 3, 1959 | |

| Preceded by | Warren R. Austin |

| Succeeded by | Winston L. Prouty |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

September 28, 1880 Barnet, Vermont |

| Died |

February 19, 1970 (aged 89) Springfield, Vermont |

| Resting place | Summer Hill Cemetery, Springfield, Vermont |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse(s) | Helen Hartness Flanders |

| Relations | James Hartness (father-in-law) |

| Children | 3 |

| Occupation |

Mechanical Engineer, Industrialist, U.S. Senator |

| Religion | Congregationalist |

Ralph Edward Flanders (September 28, 1880 – February 19, 1970) was an American mechanical engineer, industrialist and Republican U.S. Senator from the state of Vermont. He grew up on subsistence farms in Vermont and Rhode Island, became an apprentice first as a machinist, then as a draftsman, before training as a mechanical engineer. He spent five years in New York City as an editor for a machine tool magazine. After moving to Vermont, he managed and then became president of a successful machine tool company. Flanders used his experience as an industrialist to advise state and national commissions in Vermont, New England and Washington, D.C. on public economic policy.[1] He was president of the Boston Federal Reserve Bank for two years before being elected U.S. Senator from Vermont.

Flanders was noted for introducing a 1954 motion in the Senate to censure Senator Joseph McCarthy. McCarthy had made sensational claims that there were large numbers of Communists and Soviet spies and sympathizers inside the federal government and elsewhere. He used his Senate committee as a nationally televised forum for attacks on individuals whom he accused. Flanders felt that McCarthy’s attacks distracted the nation from a much greater threat of Communist successes elsewhere in the world and that they had the effect of creating division and confusion within the United States, to the advantage of its enemies. Ultimately, McCarthy's tactics and his inability to substantiate his claims led to his being discredited and censured by the United States Senate.[2]

Biographical

Flanders was born oldest of nine children in Barnet, a town in Caledonia County in northeastern Vermont, and spent much of his childhood in Rhode Island. In his autobiography, Senator from Vermont,[3] Flanders described life on his family’s subsistence farms in Vermont and Rhode Island, before he left to work in the machine tool industry for most of his career. In his first years as a machinist and draftsman, he spent his vacations traveling by bicycle over country roads between Rhode Island and Vermont and New Hampshire. Later, he lived for a time in New York City where he edited a machine tool magazine,[4] but after five years decided to move back to Vermont. In 1911, he married Helen Edith Hartness, daughter of inventor and industrialist James Hartness. They made their home in Springfield, Vermont, where Flanders became president of the Jones & Lamson Machine Company. Flanders and his wife had three children: Elizabeth (born 1912), Anna (also known as Nancy—born 1918), and James (born 1923).[5]

Professional career

Flanders’s career began with an apprenticeship, progressed into engineering, journalism, management, policy consulting, banking, finance, and finally politics when he was elected U.S. Senator from Vermont.[6]

Education and apprenticeship

Flanders had no formal education beyond the high schools that he attended in Pawtucket and Central Falls, Rhode Island. But even so, he achieved a solid grounding in mathematics, literature, Latin and Classical Greek there. Unable to afford college tuition, his father bought a two-year apprenticeship for him in 1896 at the Brown & Sharpe Manufacturing Company, a leading machine tool builder. There and through the International Correspondence School he learned machinist and drafting skills. Following his apprenticeship, he worked for various machine tool companies in New England. Despite his lack of a formal university education, he was a self-taught scholar, who read extensively in the literatures of science, engineering and the liberal arts.[7]

Technical journalism

Flanders began writing early in his career. His published articles on machine tool technology led to a job as an editor of Machine magazine in New York City. This job, which he held between 1905 and 1910, required him to cover developments in the machine tool industry. He traveled widely to visit the companies that he wrote about, which provided him many valuable contacts with leaders in the industry. As editor, he wrote articles on gear tooth systems,[8] gear cutting machinery,[9] hobs,[10] the manufacture of cans,[11] and of motor cars,[12] including Machinery’s reference series on the subject.[13][14]

In 1909, while working long hours on his definitive book on gear cutting machinery, his energy gave out and he suffered a “nervous breakdown.” He had to take time off to recover. In 1910, he accepted a job offer to work in a machine tool company in Vermont.[15] He continued to write on technical and other matters throughout his life and would develop a broader philosophy of the role of industry in society.[16][17] In 1938, he received a Worcester Reed Warner Medal in recognition for his technical writing.[18]

Engineering

Flanders's first major experience in machine design came when he helped an entrepreneur in Nashua, New Hampshire develop a box-folding machine. After that, he worked as a draftsman for General Electric until 1905, when he moved to New York City to work for Machine.[19]

In 1910, he moved to Springfield, Vermont to work as a mechanical engineer for the Fellows Gear Shaper Company.[20] He was already friendly with James Hartness, the president of the Jones & Lamson Machine Company (J&L), another company in town. In 1911, Flanders married Hartness' daughter, Helen. Shortly afterwards, Hartness hired Flanders as a manager[21] of the department at J&L that built the Fay automatic lathe.[22] Flanders redesigned that lathe to achieve higher productivity and accuracy. He became a director in 1912 and president of the company in 1933 after Hartness retired.[23][24] As president of J&L, Flanders implemented a continuous production line to manufacture the Hartness Turret Lathe instead of building each machine individually, attempting to bring some of the efficiencies of mass production to machine tool building.[25] By 1923, he had acquired and assigned more than twenty patents to J&L.[23]

Flanders and his brother, Ernest, were instrumental in developing screw thread grinding machines. These incorporated advances in thread technology (furthered by the Hartness optical comparator) and Flanders’s engineering calculations for gear-cutting machinery.[14] In 1946, the two brothers received the Edward Longstreth Medal of the Franklin Institute as recognition for this accomplishment. They had improved the accurate manufacture of die-cut screws in soft metal and solved the problem of thread-grinding on hardened work.[26]

Professional societies

Flanders became president of the National Machine-Tool Builders Association in 1923.[27] He served as president of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME) from 1934 to 1936. He was vice president of the American Engineering Council in 1937. Throughout the 1930s, Flanders served as chairman of the Screw-Thread Committee of the American Standards Association.[28] In 1942 he was awarded the Edward Longstreth Medal. In 1944 the ASME awarded him the Hoover Medal for his “public service in the field of social, civic and humanitarian effort[s].”[29] The British Institution of Mechanical Engineers made him an honorary member.[30]

Public life

In 1917, Flanders served in the Machine-Tool Section of the War Industries Board. After World War I, he oversaw the completion of international standards for screw threads through the 1930s, first as a member, then as chairman of the Screw-Thread Committee of the American Standards Association.[28]

During the Great Depression Flanders began to write about social policy. His major concern was human development in a technological era.[31] He addressed employing spiritual guidance with a “program of human values” to achieve a good life.[32] Nevertheless, his underlying goal was to achieve “full employment.”[33][34] So, he kept himself grounded in economic principles, as understood and debated during that era.[35]

In 1933, Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Secretary of Commerce, Daniel Roper, appointed Flanders to the Business Advisory Council, which was created to provide input to the administration on matters affecting business. The Council then made Flanders chairman of the Committee on Unemployment. This committee recommended addressing the problem both geographically and by industry. Flanders reported,[36] however, that when the committee made its recommendations President Roosevelt was preoccupied with augmenting the Supreme Court and ultimately chose the undistributed profits tax instead—a choice that Flanders felt discouraged capital investment.

In 1933, the National Industrial Recovery Act created the National Recovery Administration (NRA). The NRA allowed industries to create "codes of fair competition," intended to reduce destructive competition and to help workers by setting minimum wages and maximum weekly hours. Flanders was appointed to the industrial advisory board of the NRA.[6] In a speech before a 1934 conference of the code authority members, attended by President Roosevelt, Flanders opposed a proposal by the Roosevelt administration to require that businesses cut worker hours by 10 percent and raise wages by 10 percent in order to spread employment more widely. Ultimately, economic policy moved away from the codes system.[37]

In 1937, Vermont Governor George Aiken appointed Flanders to two commissions: first, the Special Milk Investigative Committee to study ways to modernize dairying in Vermont; and second, the Flood Control Commission, which chose Flanders as its chairman. This commission was to negotiate with other New England states a means of sharing costs in a system of flood-control dams.[38]

In 1940, the New England Council elected Flanders president. The governors of the New England states had established this council to study industry and commerce in their states. Flanders’s role increased his awareness of the labor and business assets in New England. He also tried to alert his peers to the prospect of U.S. involvement in the expanding Second World War.[39]

In 1942, Flanders became involved in the Committee for Economic Development (CED), an offshoot of the Business Advisory Council, whose purpose was to help re-align the nation to a peacetime economy after the war. Flanders reported[40] helping to shape the CED’s recommendations to Congress on roles for the World Bank and International Monetary Fund.

Banking and investment

Starting in the 1930s, Flanders held directorships on the boards of the Shawmut Bank (1938–41), Federal Reserve Bank of Boston (1941–44)[41] Boston and Maine Railroad, National Life Insurance Company, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Norwich University.[42]

In 1944, he was elected to a two-year term as president of the Federal Reserve Bank in Boston.[6] During this period, the bank helped establish the Boston Port Authority to revitalize the capacity for cargo from New England.[43]

In 1946, Georges Doriot, Flanders, Karl Compton and others organized American Research & Development (AR&D).[44] This was the first venture capital company to invest—according to a set of investment rules and goals—in a pool of fledgling companies. Flanders served as a director of AR&D.[45]

U.S. Senate career

Courtesy of the Vermont State Archives, Office of the Secretary of State

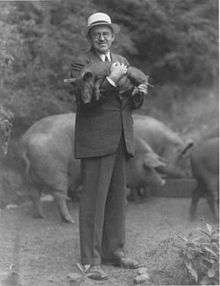

In 1940, Ralph Flanders ran an unsuccessful campaign for the U. S. Senate. His Republican primary opponent was George Aiken, the popular two-term Governor of Vermont. Although Flanders admired and liked Aiken, he felt that Aiken's "liberal" ideas would not help the nation’s economic recovery.[46] In 1990, one of Vermont’s major newspapers, The Rutland Herald described the 1940 Republican primary campaign as dirty and mean. Aiken’s side accused Flanders of selling arms to the Nazis, and Flanders’s side suggested that "Aiken was unduly influenced by his administrative assistant, a pretty 24-year-old with a fondness for power."[47] In retrospect, Flanders felt that he had allowed his campaign advisers to make too many of the decisions.[46] For example, a campaign brochure showed the candidate wearing a three-piece suit and holding a piglet in his arms. Although he had grown up on a subsistence farm and had an active interest in Vermont agriculture—especially in the type of hog shown in the picture—this had the effect of making him appear to be a phony. The Rutland Herald observed that, “In Vermont in 1940, pigs were common to many households. But so was common sense. There were many people, most in fact, who did not want as their representative someone who would wear his best clothes if he intended to be handling pigs.” Aiken won by 7,000 votes, having spent $3,219.50 to Flanders’s $18,698.45.[47] This campaign taught Flanders that “I had to be myself.”[39]

On November 1, 1946, Vermont Governor Mortimer R. Proctor appointed Flanders to the U.S. Senate as a Republican to complete the term of Republican Senator Warren Austin. Austin had just been appointed by U.S. President Harry S. Truman as Ambassador to the United Nations.[6] Flanders's appointment gave him seniority over the freshman Senators who would be elected four days later on November 5. Flanders ran for the office then, as well, and was elected to a full term. He was overwhelmingly reelected in 1952.[48] He declined to seek a third term in 1958.[49][6]

Senate record and committee assignments

Flanders's voting record in the Senate was more conservative than his senior colleague, George Aiken, and reflected Flanders's business orientation.[6] In his second term, a Republican majority allowed Flanders to obtain seats on the Joint Economic Committee—this committee acted in an investigatory and advisory capacity to both Houses of the Congress—the Finance Committee and the Committee on Armed Services.[50] These assignments reflected his interests as a senator.

Political philosophy

Flanders, although himself a conservative, espoused a constructive competition between conservatism and liberalism. He felt that liberalism represented the welfare of individual people, as opposed to organizations—governments, businesses, etc.—preserving freedom of thought and action. For him, conservatism was concerned with preserving institutions that serve the interests of people, collectively. Conservatives, according to Flanders, could find themselves offering "reasoned objections to foolish proposals" by emotionally motivated liberals.[51] He observed that, “Even in the established democracies,... the voters are easily seduced into leaving politics to skillful politicians who are themselves without a sense of general, social responsibility.”[52]

On moral law in policy formulation

Flanders had a strict Congregationalist religious beginning, which evolved with his experience into a belief in “moral law.” He felt that “recognition of moral law is as much a necessary requirement of social achievement as physical law is of material advancement.” In Flanders’s view, moral law required honesty, compassion, responsibility, cooperation, humility, and wisdom—values that all cultures hold in common.[53] For him it was an absolute standard. He spoke of a “Presence” or “daimon” that “renewed his courage” and “indicated direction” in everything he did.[54]

Flanders referred to the Marshall Plan as an important application of moral law to public policy. He said that the plan’s true purpose was to fend off Communism through the economic restoration of Europe—not to provide relief to Europe (something beyond the powers of the U.S.), nor to enhance gratitude towards the U.S., its prestige or power.[55]

On labor and business

In testifying on the Employment Act (of 1946) before the Banking and Currency Committee of the Senate in 1945, Flanders defined the “right to a job,” as implying a responsibility shared among individuals, organized labor, businesses, and governments, as follows:

- Each individual should be “productive, self-reliant and energetically in search of employment, when out of a job.”

- Organized Labor should avoid wage demands that upset costs of production in a manner that decreases the total volume of employment.

- Business should operate efficiently to allow for expansion of production and employment.

- State and local governments can help preserve human rights and property rights that foster investment, while the Federal Government should “encourage business to expand and investors to undertake new ventures.”[56]

Flanders felt that, to quell inflation, wage increases should be tied to productivity increases, rather than the cost of living. He recommended splitting gains in productivity three ways: to the worker for higher wages, to the company for higher profits and to the consumer for lower prices. He felt that with this approach everyone would benefit at the company level and in the national economy. Such an approach would require mutual respect and understanding between labor and management.[57]

Flanders’s relations with organized labor were amicable. He welcomed the United Electrical Workers Union into Jones & Lamson Machine Company. J&L became the first company in Springfield, Vermont to be unionized.[58]

On Franklin D. Roosevelt

Flanders met with President Roosevelt on several occasions. He felt that Roosevelt and his advisors did not heed Secretary of the Navy, Frank Knox’s warning that it was “easily possible that hostilities would be initiated by a surprise attack upon the fleet or the Naval Base at Pearl Harbor.” He further faulted the president for failing to recognize the growing threat of Communism in China. In Flanders’s opinion, he sold out on Mongolia, Nationalist China and Central Europe to Communist powers at the 1943 Tehran Conference. Flanders recognized the president’s political genius and leadership skills, but deplored his advocacy of raising taxes. He characterized the Roosevelt philosophy as one where re-employment “must come from Government—not private—action.”[59] Flanders felt that large social programs were an ineffective approach to solve national problems.

Cold War policies

National policy relating to the Cold War interested Flanders greatly. He was concerned about the world-wide encroachment of Communism even without force of arms. He felt that President Truman was generally a good president, but was hampered by the Roosevelt legacy of appeasing the Soviets. He also felt that Truman's commitment to bringing the Nationalist and Communist Chinese factions together into an alliance was mistaken. He endorsed the Marshall Plan as a way to avoid Communist influence in Western Europe. However, he was critical of John Foster Dulles, Secretary of State, for mishandling opportunities to create friendly alignment with Egypt and India, countries which instead sided with the Soviet Union.[60]

Flanders felt that spending 62% of federal income on defense was irrational, when the Soviet government claimed it wished to avoid nuclear conflict.[52] He advocated that the development of “A[tomic]- and H[ydrogen]-bombs be paralleled with equally intense negotiations towards disarmament.” For him, “gaining the co-operation of the Soviet government on an effective armament control,” was most important.[61]

The censure of Joseph McCarthy

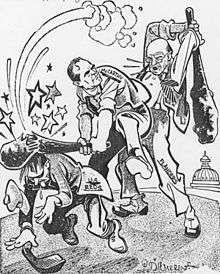

Herblock cartoon depicting Flanders attempting to deputize a reluctant Senator William F. Knowland in the effort to censure Senator Joseph McCarthy.

The original cartoon was a gift of appreciation to Senator Flanders from cartoonist Herbert Lawrence Block. Courtesy of Susan L. Flanders and Herb Block Foundation

Flanders was an early and strong critic of fellow Republican Senator Joseph McCarthy’s "misdirection of our efforts at fighting communism” and his role in “the loss of respect for us in the world at large.” He felt that rather than looking inward for communists within U.S. borders, the nation should look outward at the “alarming world-wide advance of Communist power” that would leave the United States and Canada as “the last remnants of the free world.” On March 9, 1954 he addressed Senator McCarthy on the Senate floor, expressing these concerns.[62] (McCarthy had been advised of the speech, but was absent at the time.) Apart from a brief note of encouragement after this speech, Flanders was grateful that President Eisenhower stayed out of the McCarthy controversy. Members of President Eisenhower’s cabinet passed along the message that Flanders should “lay off.”[63]

The Times-Argus newspaper of Randolph, Vermont reported:[64]

"The speech was a sensation, and the next day Vonda Bergman reported to the Herald that Flanders was unable to appear on the Senate floor because of the flood of telephone calls and telegrams, said to run 6-1 in his support. One message called his speech 'a fine example of Vermont courage, humor and decency,' while another told him, 'Your remarks brought a breath of fresh clean air from the Green Mountains.'

"Two Senate colleagues, John Sherman Cooper, R-Kentucky, and Herbert Lehman, D-New York, were among those who heaped praise on the Vermont senator. The editor of a national publication said: 'It was one of the few recent indications that the Republican Party on Capitol Hill is not wholly devoid of courageous moral leadership.' And an editorial in the Rutland Herald stated, 'The effect of the speech was to hearten that vast majority of Americans who hate communism but who also revere the Constitution.'"

.

L.D. Warren cartoon, subtitled Flanders’ Folly—How about a vote of censure for Flanders? that showed a pro-McCarthy side of the censure issue.

Originally published in the New York Journal American in 1954.

Other reactions were not so favorable. People who wrote the Rutland Herald “hinted at retribution for McCarthy’s foes” and called McCarthy “a demigod above the law of the U.S.A. ... If you disagree, you are RED.” William Loeb, owner of the Burlington Daily News, wrote, “It would take somebody as stupid as Senator Flanders to finally swallow the Democratic bait on the subject of Senator McCarthy.”[65] In a speech that Flanders did not mention in his autobiography, the Times-Argus article reported that on June 1, 1954 Flanders[64]

"...addressed the Senate on 'the colossal innocence of the junior Senator from Wisconsin.' Comparing McCarthy to 'Dennis the Menace' of cartoon fame, the Vermonter delivered a scathing address in which he lambasted the Wisconsin man for dividing the nation. 'In every country in which communism has taken over,' he reminded the Senate, 'the beginning has been a successful campaign of division and confusion.' He marveled at the way the Soviet Union was winning military successes in Asia without risking its own resources or men, and said this nation was witnessing 'another example of economy of effort...in the conquest of this country for communism.' He added, 'One of the characteristic elements of communist and fascist tyranny is at hand as citizens are set to spy upon each other.' 'Were the junior Senator from Wisconsin in the pay of the communists, he could not have done a better job for them.' 'This is a colossal innocence, indeed.'"

On June 11, 1954, Flanders introduced a resolution[6] charging McCarthy “with unbecoming conduct and calling for his removal from his committee membership.” Upon the advice of Senators Cooper and Fulbright and legal assistance from the Committee for a More Effective Congress he modified his resolution to “bring it in line with previous actions of censure.”[66] The text of the resolution of censure condemns the senator for “obstructing the constitutional processes of the Senate” when he “failed to cooperate with the Subcommittee on Privileges and Elections of the Senate Committee on Rules and Administration and acting “contrary to senatorial ethics” when he described the Select Committee to Study Censure Charges and its chairman in slanderous terms. Time reported that a “group of 23 top businessmen, labor leaders and educators... wired every U.S. Senator (except McCarthy himself) urging a favorable vote ‘to curb the flagrant abuse of power by Senator McCarthy.’"[67] The Senate censured McCarthy on December 2, 1954 by a vote of 65 to 22.[68] The Senate Republicans were split 22 to 22.[64] For a further treatment of this episode, refer to Joseph McCarthy—Censure and the Watkins Committee.

A 1990 article in the Rutland Herald characterized the reaction in Vermont to Flanders’s role in the McCarthy censure as “sour.” It concludes that Flanders’s convictions did not necessarily reflect the priorities of his constituency, which regarded the issue as “not our problem.”[47]

Legacy

Flanders was the author or coauthor of eight books, including his autobiography, Senator from Vermont.[69] He wrote about many issues: the problems of unemployment,[33][70] inflation, ways for achieving a cooperative relationship between management and labor,[71] and his belief that “moral law is natural law” and should be an integral part of everyone’s education.[72] His papers are located at the Special Collections Research Center at Syracuse University Library and at the Special Collections[73] of the University of Vermont’s Bailey-Howe Library.

During his lifetime, Flanders received more than sixteen honorary degrees from institutions that included Dartmouth College, Harvard University (LL.D.), Middlebury College (D. Sc.) and the University of Vermont (D. Eng.).[74] His wife, Helen Hartness Flanders, was a folk song collector and author of several books on New England ballads.

Flanders died in 1970 and he is buried in the Summer Hill Cemetery in Springfield, Vermont, alongside his wife, Helen, and members of the Hartness family.

Flanders’s Senate legacy has continued to inspire Vermont politicians. In his May 24, 2001 speech announcing his departure from the Republican Party, Vermont Senator James Jeffords cited Flanders three times and spoke of him as one of five Vermont politicians who, “spoke their minds, often to the dismay of their party leaders, and did their best to guide the party in the direction of those fundamental principles they believed in.”[75] In speeches to Georgetown University Law Center and Johnson State College, Senator Patrick Leahy cited Flanders as one of three Vermont politicians who showed, “the importance of standing firm in your beliefs,” “that conflict need not be hostile or adversarial”[76] and who, “rose up against abuses, against infringements upon Americans' rights when doing that was not popular.”[77]

Notes

- ↑ Herman 2012, p. 147

- ↑ Klingaman 1996

- ↑ Flanders 1961, pp. 52–58

- ↑ Flanders 1961, pp. 82–103

- ↑ Flanders 1961, pp. 104–121

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Vermont Encyclopedia 2003, p. 127

- ↑ Flanders 1961, pp. 37, 47, 64–65

- ↑ Flanders 1909a

- ↑ Flanders 1909b

- ↑ Flanders 1909c

- ↑ Flanders 1909d

- ↑ Flanders 1909e

- ↑ Flanders 1910

- 1 2 Flanders 1909f

- ↑ Flanders 1961, pp. 100–103

- ↑ Flanders 1935, pp. R1–77

- ↑ Flanders 1936a, p. 3

- ↑ Flanders 1961, p. 139

- ↑ Flanders 1961, pp. 75, 78, 81

- ↑ Flanders 1961, p. 103

- ↑ Roe 1937, p. 42,111

- ↑ ASME 1921, p. 452

- 1 2 Flanders 1961, p. 117

- ↑ The Tech 1949, p. 4

- ↑ Flanders 1925, pp. 28–37

- ↑ Flanders 1961, pp. 116–117

- ↑ Flanders 1961, p. 118

- 1 2 Flanders 1961, pp. 111–112

- ↑ ASME 1944

- ↑ Flanders 1961, p. 147

- ↑ Flanders 1930

- ↑ Flanders 1931

- 1 2 Dennison et al. 1938

- ↑ Flanders 1936a

- ↑ Flanders 1932, pp. 121–126

- ↑ Flanders 1961, pp. 179–180

- ↑ Flanders 1961, pp. 175–178

- ↑ Flanders 1961, p. 170

- 1 2 Flanders 1961, p. 186

- ↑ Flanders 1961, pp. 189–192

- ↑ Fortune 1945, pp. 135–272

- ↑ Flanders 1961, pp. 186, 209

- ↑ Flanders 1961, p. 187

- ↑ WGBH 2004

- ↑ Flanders 1961, pp. 188–189

- 1 2 Flanders 1961, p. 185

- 1 2 3 Porter & Terry 1990

- ↑ Flanders 1961, p. 209

- ↑ Flanders 1961, p. 290

- ↑ Flanders 1961, pp. 248, 250

- ↑ Flanders 1961, p. 264

- 1 2 Flanders 1963, p. 5

- ↑ Flanders 1963, p. 24

- ↑ Flanders 1961, pp. 311, 130

- ↑ Flanders 1961, pp. 222–223

- ↑ Flanders 1961, p. 194

- ↑ Flanders 1961, p. 310

- ↑ Editors 1970

- ↑ Flanders 1961, pp. 201–204, 182

- ↑ Flanders 1961, pp. 228, 303–306, 277–278

- ↑ Flanders 1961, p. 237

- ↑ Flanders 1954

- ↑ Flanders 1961, pp. 267, 255–257, 262

- 1 2 3 Crozier 1979

- ↑ Hill 1989

- ↑ Flanders 1961, pp. 260, 261, 267

- ↑ Time 1954

- ↑ Senate Historical Office 1995

- ↑ Flanders 1961

- ↑ Flanders 1936b

- ↑ Flanders 1949a

- ↑ Flanders 1956

- ↑ Flanders 1949b

- ↑ Massachusetts Institute of Technology 1970

- ↑ Jeffords 2001

- ↑ Leahy 2008

- ↑ Editors 2006

References

Flanders

- Flanders, Ralph E. (February 1909a), "Interchangeable Involute Gear Tooth Systems", Journal of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (2410 F).

- Flanders, Ralph E. (February 1909b), "Recent developments in gear-cutting machinery", Machinery (2242 C).

- Flanders, Ralph E. (January 1909c), "How many gashes should a hob have?", Machinery (1550 C).

- Flanders, Ralph E. (1909d), "Making solderless cans for food products", Machinery (7500 C).

- Flanders, Ralph E. (October 1909e), "The design and manufacture of a high-grade motor car— Illustrated detailed description of the factory, methods and products of the Stevens-Duryea Co.", Machinery (8279 C).

- Flanders, Ralph E. (1909f), Gear-cutting machinery, comprising a complete review of contemporary American and European practice, together with a logical classification and explanation of the principles involved, New York: J. Wiley & Sons.

- Flanders, Ralph E. (1910), Construction and Manufacture of Automobiles, Machinery’s Reference Series. No. 60, New York: The Industrial Press.

- Flanders, Ralph E. (1925), Design manufacture and production control of a standard machine, 46, New York: ASME Transactions.

- Flanders, Ralph E. (1930), "The new age and the new man", in Beard, Charles A., Toward Civilization, New York: Longmans, Green & Co..

- Flanders, Ralph E. (1931), Taming Our Machines; The Attainment of Human Values in a Mechanized Society, New York: R.R. Smith, Inc.

- Flanders, Ralph E. (1932), "Limitations and possibilities of economic planning", Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science (published July 1932), 162 (16z), p. 27, doi:10.1177/000271623216200106.

- Flanders, Ralph E. (1935), New pioneers on a new frontier, 46, New York: ASME Transactions, pp. R1–77.

- Flanders, Ralph E. (1936a), "New pioneers on a new frontier", Mechanical Engineering Magazine, p. 3.

- Flanders, Ralph E. (1936b), Platform for America, New York: Whittlesy House, McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc.

- Dennison, Henry S.; Filene, L.; Flanders, R.; Leeds, M. (1938), Toward full employment, New York: McGraw-Hill Book.

- Flanders, Ralph E. (1949a), The Function of Management in American Life, Palo Alto, California: Graduate School of Business, Stanford University.

- Flanders, Ralph E. (1949b), Limitations of national policy: speech of Hon. Ralph E. Flanders of Vermont in the Senate of the United States August 11, 1949, Special Collections, University of Vermont Library.

- Flanders, Ralph E. (1954), "Activities of Senator Mcarthy—The World Crisis", Congressional Record—Proceedings and Debates of the 83rd Congress, Second Session, Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office (published March 9, 1954).

- Flanders, Ralph E. (1956), Letter to a generation, Boston: Beacon Press.

- Flanders, Ralph E. (1961), Senator from Vermont, Boston: Little, Brown.

- Flanders, Ralph E. (1963), A Search for Meaning, Springfield, Vermont: Hurd’s Offset Printing.

Others

- ASME (1921), A.S.M.E. mechanical catalog and directory, Volume 11, American Society of Mechanical Engineers.

- ASME (1944), Hoover Medal awardees, Asme.org, retrieved 2013-05-04

- Crozier, Barney (September 29, 1979), "Vermont Senator's Speech Heralded McCarthy's End", Times-Argus (Randolph, Vermont).

- Editors (February 21, 1970), "In our opinion—Sen. Flanders of Vermont", Burlington Free Press.

- Editors (December 17, 2006), "Leahy takes lead on Judiciary Committee", Burlington Free Press, retrieved January 4, 2010.

- Fortune (August 1945), "Flanders of New England", Fortune Magazine, vol. 32 no. 2.

- Herman, Arthur (2012), Freedom's Forge: How American Business Produced Victory in World War II, New York, NY: Random House, ISBN 978-1-4000-6964-4.

- Hill, Tom (December 3, 1989), "Vt.'s Senator Ralph Flanders took on McCarthy, and won", Sunday Rutland Herald and Sunday Times Argus (Vermont), pp. E1, E4.

- Jeffords, James (May 24, 2001), Transcript: Jeffords statement, CNN InsidePolitics, retrieved January 4, 2010.

- Klingaman, William (1996), The Encyclopedia of the McCarthy Era, Facts on File, ISBN 0-8160-3097-9.

- Leahy, Patrick (May 17, 2008), Senator Patrick Leahy Delivers 2008 Commencement Address, Johnson State College, retrieved January 4, 2010.

- Massachusetts Institute of Technology (March 6, 1970), "Ralph Edward Flanders 1880-1970", Resolutions of the Corporation of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology on the death of Ralph Edward Flanders Life Member Emeritus.

- Porter, Bill; Terry, Stephen C. (September 9, 1990), "Down & Dirty—The Aiken-Flanders Primary of 1940", Vermont Sunday Magazine of the Rutland Herald and the Times Argus of Rutland and Randolph, Vermont.

- Roe, Joseph Wickham (1937), James Hartness: A Representative of the Machine Age at Its Best, New York, New York, USA: American Society of Mechanical Engineers, LCCN 37016470, OCLC 3456642, ;. link from HathiTrust.

- Senate Historical Office (1995), United States Senate Historical Office: "The Censure Case of Joseph McCarthy of Wisconsin (1954)", Senate.gov, retrieved 2013-05-04.

- The Tech (November 15, 1949), "Sen. Flanders to Discuss Welfare" (PDF), The Tech (MIT newspaper): 4.

- Time (August 2, 1954), "The Dispensable Man", Time Magazine.

- Vermont Encyclopedia, Editors (2003), "Flanders, Ralph E.", in Duffy, John J.; Hand, Samuel B.; Orth, Ralph H., The Vermont Encyclopedia, Lebanon, New Hampshire: University Press of New England, ISBN 1-58465-086-9.

- WGBH, Public Broadcasting Service (2004-06-30), Who made America—George Doriot, Pbs.org, retrieved 2013-05-04.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ralph Flanders. |

- Works by or about Ralph Flanders at Internet Archive

- United States Congress Biography

- Times-Argus Article on the Flanders's Censure of McCarthy.

- Vermont Public Radio commentary commemorating the 50th anniversary of Flanders's senate speech on McCarthy.

Further reading

- Margolis, Jon (July 11, 2004), "A mighty fall—How an obscure Vermont senator brought down Joseph McCarthy 50 years ago.", Sunday Rutland Herald & Sunday Times-Argus, pp. 8–11

- Shannon, William V. (March 14, 1954), "An old-timer says a mouthful", New York Post, pp. 2M

| United States Senate | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Warren R. Austin |

U.S. Senator (Class 1) from Vermont 1946–1959 Served alongside: George Aiken |

Succeeded by Winston L. Prouty |