Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani

| Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani | |

|---|---|

| اکبر هاشمی رفسنجانی | |

| |

| Chairman of Expediency Discernment Council | |

|

Assumed office 6 February 1989 | |

| Appointed by | Ali Khamenei |

| Preceded by | Ali Khamenei |

| Chairman of the Assembly of Experts | |

|

In office 25 July 2007 – 8 March 2011 | |

| Preceded by | Ali Meshkini |

| Succeeded by | Mohammad-Reza Mahdavi Kani |

| 4th President of Iran | |

|

In office 3 August 1989 – 3 August 1997 | |

| Supreme Leader | Ali Khamenei |

| First Vice President | Hassan Habibi |

| Preceded by | Ali Khamenei |

| Succeeded by | Mohammad Khatami |

| Chairman of the Parliament | |

|

In office 28 July 1980 – 3 August 1989 | |

| First Deputy |

Ali Akbar Parvaresh Mohammad Mousavi Khoeiniha Mohammad Yazdi Mehdi Karroubi |

| Preceded by | Yadollah Sahabi |

| Succeeded by | Mehdi Karroubi |

| Member of the Assembly of Experts | |

|

Assumed office 15 August 1983 | |

| Constituency | Tehran Province |

| Majority | 2,301,492 (5th term) |

| Tehran's Friday Prayer Interim Imam | |

|

In office 3 July 1981 – 17 July 2009 | |

| Appointed by | Ruhollah Khomeini |

| Member of the Parliament of Iran | |

|

In office 28 May 1980 – 3 August 1989 | |

| Constituency | Tehran, Rey, Shemiranat and Eslamshahr |

| Majority | 1,891,264 (81.9%; 2nd term) |

| Minister of Interior Acting | |

|

In office 6 November 1979 – 12 August 1980 | |

| Appointed by | Islamic Revolution Council |

| Preceded by | Hashem Sabbaghian |

| Succeeded by | Mohammad-Reza Mahdavi Kani |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

25 August 1934 Bahreman, Persia |

| Nationality | Iranian |

| Political party | Combatant Clergy Association (Inactive since 2009)[1] |

| Other political affiliations | Islamic Republican Party (1979–1987) |

| Spouse(s) | Effat Marashi (m. 1958)[2] |

| Children |

Mohsen (b. 1961) Fatemeh (b. 1961) Faezeh (b. 1962) Mehdi (b. 1969) Yasser (b. 1971) |

| Religion | Twelver Shia Islam |

| Signature |

|

| Website | Official Website |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance |

|

| Commands |

|

| Battles/wars | Iran–Iraq War |

| Awards |

|

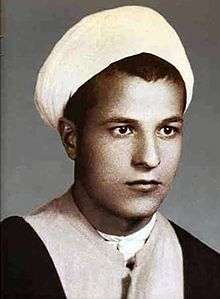

Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani (Persian: اکبر هاشمی رفسنجانی, translit. Akbar Hāshemī Rafsanjānī ![]() pronunciation ) or Hashemi Bahramani (هاشمی بهرمانی), born 25 August 1934) is an influential Iranian politician and writer, who was the fourth president of Iran. He was the head of the Assembly of Experts from 2007 until 2011 when he decided not to nominate himself for the post.[4][5] He is also the chairman of the Expediency Discernment Council of Iran.

pronunciation ) or Hashemi Bahramani (هاشمی بهرمانی), born 25 August 1934) is an influential Iranian politician and writer, who was the fourth president of Iran. He was the head of the Assembly of Experts from 2007 until 2011 when he decided not to nominate himself for the post.[4][5] He is also the chairman of the Expediency Discernment Council of Iran.

During the Iran–Iraq War Rafsanjani was the de facto commander-in-chief of the Iranian military. Rafsanjani was elected chairman of the Iranian parliament in 1980 and served until 1989. Rafsanjani also served as president of Iran from 1989 to 1997. He played an important role in the choice of Ali Khamenei as Supreme Leader.[6] In 2005 he ran for a third term in office, placing first in the first round of elections but ultimately losing to rival Mahmoud Ahmadinejad in the run-off round of the 2005 election.

Rafsanjani has been described as a pragmatic conservative, while The Economist has described him as a "veteran kingmaker."[7] He supports a free market position domestically, favoring privatization of state-owned industries, and a moderate position internationally, seeking to avoid conflict with the United States and the West.[8]

In 1997 during the Mykonos trial in Germany, it was declared that Hashemi Rafsanjani (the then president of Iran) alongside of Ayatollah Ali Khameni (supreme leader), Ali-Akbar Velayati (the then foreign minister) and Ali Fallahian (Intelligence Minister) has had role in assassination of Iran's opposition activists in Europe.[9] He is considered to be the richest person in Iran.[10]

On 11 May 2013, Rafsanjani entered the race for the June 2013 presidential election,[11] but on 21 May he was disqualified by the Guardian Council.

Early life and education

Rafsanjani was born in the village of Ghahraman near the city of Rafsanjan in Kerman Province to a wealthy family of pistachio farmers.[12][13] He has eight siblings.[14] His mother, Hajie Khanom Mahbibi Hashemi, died at the age of 90 on 21 December 1995.[15]

He studied theology in the city of Qom with Ayatollah Khomeini, whose close follower he became.[16]

Speaker of the Parliament

Ayatollah Rafsanjani was the Speaker of Parliament of Iran for 9 years. He was elected as the speaker in 1980 in the first season of Parliament after the Iranian Revolution. He was also chairman in the second season. After the death of Ruhollah Khomeini, founder of the Islamic Republic, he joined the 1989 presidential race and became the President, leaving Parliament.

Presidency

Rafsanjani adopted an "economy-first" policy, supporting a privatization policy against more state owned economic tendencies in the Islamic Republic.[17] Another source describes his administration as "economically liberal, politically authoritarian, and philosophically traditional" which put him in confrontation with more radical deputies in the majority in the Majles of Iran.[18]

As president, Rafsanjani was credited with spurring Iran's reconstruction following the 1980-88 war with Iraq.[19] Rafsanjani is known to be popular with the upper and middle classes, partially due to his economic reforms during his tenure and support for human rights (in comparison to the Khomeini years), which have been widely perceived as successful for the most part. However, his reconstruction efforts failed to reach the rural or war zones where they needed them the most, leaving him unpopular with the majority of the rural, veteran, and working class population. His reforms, despite attempting to curb the powers of the ultra-conservatives, failed to do so and the Iranian Revolutionary Guards would get increasing powers from Khamenei during his presidency. He was also accused of corruption by both conservatives[20] and reformists,[21] and known for tough crackdowns on dissent.

Domestic policy

Rafsanjani advocated a free market economy. With the state's coffers full, Rafsanjani pursued an economic liberalisation policy.[22] Rafsanjani's support for a deal with the United States over Iran's nuclear program and his free-market economic policies contrasted with Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and his allies, who advocate maintaining a hard line against Western intervention in the Middle East while pursuing a policy of economic redistribution to Iran's poor.[23] By espousing World Bank inspired structural adjustment policies, Rafsanjani desired a modern industrial-based economy integrated into the global economy.[24]

Rafsanjani urged universities to cooperate with industries. Turning to the quick pace of developments in today's world, he said that with "the world constantly changing, we should adjust ourselves to the conditions of our lifetime and make decisions according to present circumstances".[25] Among the projects he initiated are Islamic Azad University.[26][27]

During his presidency, a period in which Rafsanjani is described by western media sources as having been the most powerful figure in Iran, people ordered executed by the judicial system of Iran included political dissidents, drug offenders, Communists, Kurds, Bahais, and even Islamic clerics.[28]

The Iranian Mojahedin were recognized as a terrorist organization by both the Iranian government as well as the United States CIA. Regarding the Mojahedin, Rafsanjani said (Ettela'at, 31 October 1981):

| “ | God's law prescribes four punishments for them (the Mojahedin). 1-Kill them. 2-Hang them, 3-Cut off their hands and feet 4-Banish them. If we had killed two hundred of them right after the Revolution, their numbers would not have mounted this way. I repeat that according to the Quran, we are determined to destroy all [Mojahedin] who display enmity against Islam". | ” |

Rafsanjani also worked with Khamenei to maintain the stability of government after the death of Khomeini..[29]

Foreign policy

Following years of deterioration in foreign relations under Khomeini during the Iran-Iraq war, Rafsanjani sought to rebuild ties with Arab states[30] as well as with countries in Central Asia and the Caucasus, including Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan.[31] However, relations with European countries and the United States remained poor, even though Rafsanjani had a track record of handling difficult situations and defusing crises.[32]

He condemned both the United States and Iraq during the Persian Gulf War in 1991. After the war he strove to renew close ties with the West, although he refused to lift Khomeini's fatwa against the British author Salman Rushdie.[33]

Rafsanjani has said that Iran is ready to assist Iraq, "expecting nothing in return". On the other hand, he has said that "peace and stability" is a function of the "evacuation of the occupiers."[34]

Iran gave humanitarian help to the victims of the conflict. Iran sent truckloads of food and medicine to Iraq, and thousands of Kuwaiti refugees were given shelter in Iran.[35]

Rafsanjani voiced support to Prince Abdullah's peace initiative and to "everything the Palestinians agree to". He also stated that what he called "Iran's international interests" must take precedence over those of Iranian allies in Syria and Lebanon.[32]

Ayatollah Rafsanjani is a supporter of Iran's nuclear program. In 2007 Rafsanjani reiterated that the use of weapons of mass destruction was not part of the Islamic Republic culture. Rafsanjani said: "You [US and allies] are saying that you cannot trust Iran would not use its nuclear achievements in the military industries, but we are ready to give you full assurances in this respect."[36] According to The Economist, he is regarded by many Iranians "as the only person with the guile and clout to strike a deal with the West to end economic sanctions" imposed upon the country due to its nuclear program.[37]

Economy

During the presidential term of Rafsanjani GNP did not reach beyond the $1.500 mark. In fact it remained below the needs of an average family. Also increasing the food prices was another economic situation in his term. [38]

After presidency

Post-presidency, Rafsanjani delivered a sermon at Tehran University in the summer of 1999 praising government use of force to suppress student demonstrations.[28]

In 2000, in the first election after the end of his presidency, Rafsanjani ran again for Parliament. In the Tehran contest, Rafsanjani came in 30th, or last, place. At first he was not among the 30 representatives of Tehran elected, as announced by the Iranian Ministry of the Interior, but the Council of Guardians then ruled numerous ballots void, leading to accusations of ballot fraud in Rafsanjani's favor.[28] Rafsanjani thus became a Majlis representative, but resigned before being sworn in. He explained that he felt he was "able to serve the people better in other posts".

Rafsanjani is the current Chairman of the Expediency Discernment Council, that resolves legislative issues between the Majlis and the Council of Guardians.

In December 2006, Rafsanjani was elected to the Assembly of Experts representing Tehran with more than 1.5 million votes, which was more than any other candidate. Ahmadinejad opponents won majority of local election seats. On 4 September 2007 he was elected Chairman of the Assembly of Experts, the body that selects Iran's supreme leader, in what was considered a blow to the supporters of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. He won the chairmanship with 41 votes of the 76 cast. His ultraconservative opponent, Ayatollah Ahmad Jannati, received 31 votes.[39] He was running against Ahmad Jannati. Rafsanjani was re-elected to the position on 10 March 2009, running against Mohammad Yazdi. He received 51 votes compared to Yazdi's 26.[40][41] On 8 March 2011 he withdrew from the election. Ayatollah Mohammad Reza Mahdavi Kani is the new Chairman.[42]

In more recent years, Rafsanjani has advocated freedom of expression, tolerance and civil society. In a speech on 17 July 2009, Rafsanjani criticized restriction of media and suppression of activists, and put emphasis on the role and vote of people in the Islamic Republic constitution.[43][44][45] The event has been considered by analysts as the most important and most turbulent Friday prayer in the history of contemporary Iran.[46] Nearly 1.5-2.5 million people attended the speech in Tehran.[47]

Crisis following 2009 election

2009 election protests

| Wikinews has related news: Former Iranian president Hashemi Rafsanjani leads Friday prayers |

During the 2009 Presidential election, Rafsanjani's former rival and incumbent president, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, won a (disputed) landslide victory over challenger Mir-Hossein Mousavi. His daughter was arrested on 21 June by plain clothes Basij during the subsequent protest[48] and later sentenced to six months in jail on charges of spreading propaganda against the Islamic Republic.[49]

Ayatollah Hashemi Rafsanjani was chairman of the Assembly of Experts, which is responsible for appointing or removing the Supreme Leader, who has been rumored to not be in the best of health.[50] After the disputed results of the election were certified by the Supreme Leader, Rafsanjani was reported to have called a meeting of the Assembly of Experts, but it is unknown what the outcome or disposition of this meeting actually was.[51] During this time Rafsanjani relocated from Tehran to Qom, where the country's religious leaders sit. However, for the most part, Rafsanjani was silent about the controversial 12 June election and its aftermath.[52]

On 17 July 2009, Rafsanjani publicly addressed the election crisis, mass arrests and the issue of freedom of expression during Friday prayers. The prayers witnessed an extremely large crowd that resembled the Friday prayers early after the revolution. Supporters of both reformist and conservative parties took part in the event. During prayers, Rafsanjani argued the following:[53]

All of us the establishment, the security forces, police, parliament and even protestors should move within the framework of law... We should open the doors to debates. We should not keep so many people in prison. We should free them to take care of their families. ... It is impossible to restore public confidence overnight, but we have to let everyone speak out. ... We should have logical and brotherly discussions and our people will make their judgments. ... We should let our media write within the framework of the law and we should not impose restrictions on them. ... We should let our media even criticize us. Our security forces, our police and other organs have to guarantee such a climate for criticism.[54]

Assembly of Experts election

On 8 March 2011 Rafsanjani lost his post as chairman of the powerful Assembly of Experts, replaced by Ayatollah Mohammad-Reza Mahdavi Kani. Rafsanjani stated that he withdrew from the election for chairman to "avoid division." The loss was said to be the result of intensive lobbying "in recent weeks" by "hardliners and supporters" of president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, and part of Rafsanjani's gradual loss of power over the years.[55] It was said that Rafsanjani would be dismissed as head of Expediency Discernment Council but he was re-appointed for another five years term on 14 March 2012 by Ali Khamenei.

2013 Presidential elections

On 11 May 2013 Rafsanjani registered for the 14 June presidential election with just minutes to spare.[56] Former reformist president Mohammad Khatami endorsed him.[57] However, on 21 May 2013, Iran's electoral watchdog disqualified him from standing in the presidential election.[58] On 11 June 2013, Rafsanjani endorsed moderate Hassan Rouhani in the elections for Iran's presidency saying the candidate was "more suitable" than others for presidency.[59]

Controversies

Accusations

Rafsanjani is currently sought by the Argentinian government for ordering the 1994 AMIA bombing in Buenos Aires.[60] It is based on the allegation that senior Iranian officials planned the attack in an August 1993 meeting, including Khamanei, the Supreme Leader, Mohammad Hejazi, Khamanei's intelligence and security advisor, Rafsanjani, then president, Ali Fallahian, then intelligence minister, and Ali Akbar Velayati, then foreign minister.[61]

In 1997 during the Mykonos trial in Germany, it was declared that Rafsanjani, the then president of Iran, alongside of Ayatollah Khamenei, Velayati and Fallahian had role in assassination of Iran's opposition activists in Europe.

Tension with Ahmadinejad

After his loss at the presidential elections in 2005, a growing tension between him and President Ahmadinejad arose. Rafsanjani has criticized Ahmadinejad's administration several times for conducting a purge of government officials,[62] slow move towards privatization[63] and recently hostile foreign policy in particular the atomic energy policy.[64] In return Ahmadinejad fought back that Rafsanjani failed to differentiate privatization with the corrupt takeover of government-owned companies and of foreign policies which led to sanctions against Iran in 1995 and 1996.[65][66] He also implicitly denounced Rafsanjani and his followers by calling those who criticize his nuclear program as "traitors".[67]

During a debate with Mirhossein Moussavi in 2009 presidential election, Ahmadinejad accused Hashemi of corruption. Hashemi released an open letter in which he complained about what he called the president's "insults, lies and false allegations" and asked the country's supreme leader, Ali Khamenei, to intervene.[68]

Political parties

Although Rafsanjani has been a member of the pragmatic-conservative Combatant Clergy Association, he has a close bond to the reformist Kargozaran party. He has been seen as flip-flopping between conservative and reformist camps since the election of Mohammad Khatami, supporting reformers in that election, but going back to the conservative camp in the 2000 parliamentary elections as a result of the reformist party severely criticizing and refusing to accept him as their candidate. Reformists, including Akbar Ganji, accused him of involvement in murdering dissidents and writers during his presidency. In the end, the major differences between the Kargozaran and the reformists party weakened both and eventually resulted in their loss at the presidential elections in 2005. However, Rafsanjani has regained close ties with the reformers since he lost the 2005 presidential elections to Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.[22]

Electoral history

| Year | Election | Votes | % | Rank | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | Parliament | 1,151,514 | ≈54 | 15th | Won |

| 1982 | Assembly of Experts | ≈2,200,000 | ≈69 | Won | |

| 1984 | Parliament | 1st | Won | ||

| 1988 | Parliament | 1st | Won | ||

| 1989 | President | 15,537,394 | 96.1 | 1st | Won |

| 1990 | Assembly of Experts | Won | |||

| 1993 | President | 1st | Won | ||

| 1998 | Assembly of Experts | Won | |||

| 2000 | Parliament | 30th | Won but Withdrew | ||

| 2005 | President | 1st | Went to run-off | ||

| President run off | 2nd | Lost | |||

| 2006 | Assembly of Experts | 1st | Won | ||

| 2013 | President | – | Disqualified | ||

| 2016 | Assembly of Experts | 1st | Won | ||

Personal life

From his marriage to Effat Mar'ashi in 1962, Rafsanjani has three sons: Mohsen, Mehdi, and Yasser, as well as two daughters, Fatemeh and Faezeh. Only Faezeh Hashemi chose a political life, which led to her becoming a Majlis representative and then the publisher of the newspaper Zan (woman), which was closed in February 1999.[69]

Family tree

| Mah-Bibi Safarian | Mirza Ali | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Effat Marashi | Akbar Hashemi Bahramani | Mohammd | Mahmoud | Ahmad | Ghasem | Tayyebeh | Tahereh | Sedigheh | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mohsen | Fatemeh | Faezeh | Mehdi | Yasser | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Books

- Memories

- The Combat Era is the title of his book on the events before the 1979 revolution. His devotion to Rouhollah Khomeini, his sympathy with the national movement including Mohammad Mosaddegh and Mahdi Bazargan is seen in this book. In this book, he even shows interest in western democracy.[72]

- Amir Kabir: the Hero of Fighting against Imperialism (1968)[73]

- Tafsir Rahnama[74]

- Explicit Letters

In addition, the full text of his Friday Prayer sermons and his congress keynote speeches are also published separately.[75] Based on his diary, viewpoints, speeches and interviews, several independent books have been published so far.

Analysis

Although he was a close follower of Ayatollah Khomeini and considered as a central elite during Islamic revolution, at the same time he was fan of reconstruction of shattered country after war and according to this fact, he selects his cabinets from western-educated technocrats and social reformers. His cabinet largely was a reformist one. Rafsanjani acquired both the support of Imam Khomeini in one hand and Majlis in other hand. In fact, he tries to transfer the economy towards the free-market system. Of course there was a gap among Rafsanjani and Khatami and reform agenda because of his partnership with those who were conservative. Anyway the first face of reformist movements begins by Rafsanjani. [76]

See also

References

- ↑ "روحانی، بهانه انشعاب جامعه روحانیت؟" [Rouhani: Excuse for Split in Combatant Clergy Association?]. Shargh (in Persian). Alef. 18 June 2016. Retrieved 25 June 2016.

- ↑ Sciolino, Elaine (19 April 1992). "Rafsanjani Sketches Vision of a Moderate, Modern Iran". New York Times. Archived from the original on 21 June 2009. Retrieved 9 June 2009.

- ↑ Poursafa, Mahdi (20 January 2014). گزارش فارس از تاریخچه نشانهای نظامی ایران، از «اقدس» تا «فتح»؛ مدالهایی که بر سینه سرداران ایرانی نشسته است [From "Aghdas" to "Fath": Medals resting on the chest of Iranian Serdars] (in Persian). Fars News. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

- ↑ In Rafsanjani’s election to key post, Iran moderates see victory Indian Express, 6 September 2007

- ↑ Iran's Rafsanjani Loses Key Post On Assembly Of Experts Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, 8 March 2011

- ↑ Ian Black. "Iran election: Rafsanjani defends decision to stand as his 'national duty'". The Guardian.

- ↑ "Iranian politics after the nuclear deal". The Economist. 28 May 2016. Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- ↑ RK Ramazani Revolutionary Iran: Challenge and Response in the Middle East', The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1987.

- ↑ Murder at Mykonos: Anatomy of a Political Assassination Iran Human Rights Documentation Center, 2009

- ↑ BBC News Profile: Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, 19 June 2009

- ↑ "Iran's Rafsanjani Registers for presidential race". AP. Archived from the original on 11 June 2013. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ↑ Ayatollah Akbar Hashemi-Rafsanjani from Radio Free Europe

- ↑ "Iran Report: May 9, 2005". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty.

- ↑ "Rafsanjani's possible return creates a buzz in Tehran". Financial Times.

- ↑ "Profile - Hoj. Ali Akbar Rafsanjani". APS Review Gas Market Trends. 19 April 1999. Retrieved 19 June 2013.

- ↑ "Profile: Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani". BBC News.

- ↑ Pasri, Trita, Treacherous Alliance: The Secret Dealings of Israel, Iran and the United States, Yale University Press, 2007, p.132

- ↑ Brumberg, Daniel, Reinventing Khomeini: The Struggle for Reform in Iran, University of Chicago Press, 2001, p.153

- ↑ John Pike. "Hojjatoleslam Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani". Globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 2011-01-28.

- ↑ "Is Khameini's Ominous Sermon a Turning Point for Iran?". Time. 19 June 2009.

- ↑ "It is a quirk of history that Mr. Rafsanjani, the ultimate insider, finds himself aligned with a reform movement that once vilified him as deeply corrupt." Slackman, Michael (21 June 2009). "Former President at Center of Fight Within Political Elite". New York Times.

- 1 2 Rafsanjani's political life reviewed — in Persian.

- ↑ "Voice of ambition". The Guardian. London. 23 June 2006. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ↑ Book: Factional politics in post-Khomeini Iran By Mehdi Moslem

- ↑ Rafsanjani urges universities to cooperate with industries, IRNA

- ↑ Rafsanjani to Ahmadinejad: We Will Not Back Down, ROOZ)

- ↑ يادگارهاي مديريت 16 ساله :: RajaNews

- 1 2 3 Sciolino, Elaine (19 July 2009). "Iranian Critic Quotes Khomeini Principles". New York Times.

- ↑ David Menashri (2001). post revolutionary politics In iran. Frank Cass. p. 62.

- ↑ Mafinezam, Alidad and Aria Mehrabi, Iran and its Place Among Nations, Greenwood, 2008, p.37

- ↑ Mohaddessin, Mohammad, Islamic Fundamentalism, Anmol, 2003, pp.70–72

- 1 2 Al-Ahram Weekly|Region|Showdown in Tehran

- ↑ Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani Biography - Biography.com

- ↑ Iran ready for comprehensive assistance to Iraqi nation - Rafsanjani - Irna

- ↑ Iran's Persian Gulf Policy: From Khomeini to Khatami, by Christin Marschall

- ↑ John Pike. "Rafsanjani reassures West Iran not after A-bomb". globalsecurity.org.

- ↑ "A candidacy conundrum". The Economist.

- ↑ Anoushiravan Enteshami & Mahjoob Zweiri (2007). Iran and the rise of Neoconsevatives,the politics of Tehran's silent Revolution. I.B.Tauris. p. 19.

- ↑ Slackman, Michael (5 September 2007). "Ex-President Back in Spotlight in Iran, as He Wins Leadership of Council". The New York Times.

- ↑ انتخاب مجدد هاشمی به ریاست خبرگان (in Persian). March 10, 2009.

- ↑ انتخاب مجدد هاشمی رفسنجانی به ریاست مجلس خبرگان (in Persian). BBC Persian. 10 March 2009.

- ↑ Rafsanjani ousted from Iranian post, Al Jazeera English, 8 March 2011

- ↑ بهروز کارونی (2009-07-17). "اکبرین: هاشمی به صراحت وجود اختناق را تایید کرد - © 2011تمام حقوق این وبسایت بر اساس قانون کپیرایت برای رادیو فردا محفوظ است". Radiofarda.com. Retrieved 2011-01-28.

- ↑ Daragahi, Borzou; Mostaghim, Ramin (18 July 2009). "Iranian protesters galvanized by sermon". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ "Clashes as key Iranian cleric warns leaders". CNN. 18 July 2009.

- ↑ "اعتراضیترین نمازجمعهی تاریخ معاصر ایران". Deutsche Welle. 17 July 2009. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- ↑ "پايگاه خبری تحليلی فرارو - جمعيت حاضر در نماز جمعه تهران چقدر بودند؟". Fararu. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- ↑ Amir Farshad Ebrahimi's video taped confession transcript

- ↑ "Hashemi Rafsanjani's daughter arrested". PressTV. 24 September 2012.

- ↑ Iran Sources Dismiss Buzz Over Khamenei Health RFEFL, 15 October 2009

- ↑ World leaders urged by Iran's opposition party to reject Ahmadinejad's alleged victory Julian Borger and Ian Black, The Guardian, 14 June 2009

- ↑ "Rafsanjani's future at stake in Iran turmoil". Reuters. 26 June 2009.

- ↑ "Rafsanjani backs tolerance, dialogue" Los Angeles Times, 2009

- ↑ Daragahi, Borzou; Mostaghim, Ramin (17 July 2009). "In Iran, tensions build ahead of Rafsanjani's Friday sermon". The Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ Iran: Ex-Leader Rafsanjani Loses Role, by AP / Ali Akbar Dareini, 8 March 2011

- ↑ Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani to stand in Iran presidential election| The Guardian

- ↑ Rafsanjani's last-minute entry transforms Iranian race - Yahoo! News

- ↑ Bahmani, Arash (22 May 2013). "The Arbiter of State Expediency is Disqualified". Rooz. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

- ↑ "اعلام حمایت هاشمی رفسنجانی از روحانی". BBC Persian.

- ↑ Iranian terror network in S. America

- ↑ Barsky, Yehudit (May 2003). "Hizballah" (Terrorism Briefing). The American Jewish Committee. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ↑ "Rafsanjani slams Iran president". BBC News. 17 November 2005. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ↑ Harrison, Frances (23 January 2007). "Criticism of Ahmadinejad mounts". BBC News. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ↑ Rafsanjani, Ahmadinejad Engage in New War of Words (ROOZ: English)

- ↑ حمله به دولت در اولين كنفرانس خبري پس از 9 سال Raja News

- ↑ نمیپذیریم عده ای حرف خود را به نام سند چشم انداز مطرح کنند Raja News

- ↑ "Iran president attacks 'traitors'". BBC News. 12 November 2007. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ↑ Worth, Robert F. (11 June 2009). "In Iran Race, Ex-Leader Works to Oust President". The New York Times.

- ↑ Buchta, Wilfried (2000). Who Rules Iran? The Structure of Power in the Islamic Republic (PDF). Washington, DC: The Washington Inst. for Near East Policy [u.a.] ISBN 0-944029-39-6.

- ↑ "تصاویر منتشر نشده خانواده آیت الله هاشمی" (in Persian). fararu.com. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

- ↑ "شجره نامه هاشمی رفسنجانی" (in Persian). shafaf.ir. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

- ↑ Moslem, Mehdi. Factional politics in post-Khomeini Iran. New York: Syracuse University Press, 2002. 371. ISBN ISBN 0-8156-2978-8.

- ↑ کتابخانه مرکزی دانشگاه صنعتی شریف: اميركبير يا قهرمان مبارزه با استعمار, هاشمي رفسنجاني، اكبر

- ↑ یزدی،محمد علی. "تفسیر راهنما از آغاز تا کنون". noormags.com.

- ↑ "فارسی - ايران - نگاهی دیگر: خاطرات اکبر هاشمی رفسنجانی و حذف روایت کشتار ۶۷". BBC News.

- ↑ Anoushiravan Enteshami & Mahjoob Zweiri (2007). Iran and the rise of Neoconservatives, the politics of Tehran's silent Revolution. I.B.Tauris. p. 4-5.

Further reading

- Pesaran, Evaleila, Iran's Struggle for Economic Independence: Reform and Counter-Reform in the Post-Revolutionary Era, Editor: Taylor & Francis

- Amir Arjomand, Said, After Khomeini: Iran Under His Successors , Editor: Oxford University Press

- Moin, Baqer, (1999) Khomeini: Life of the Ayatollah, Editor: I.B.Tauris

- Nabavi, Negin,Iran: From Theocracy to the Green Movement, Editor: Palgrave Macmillan

External links

Official

Other

- All News About Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani

- Iranian Economy in Six Snapshots

- Rafsanjani's response to some allegations (ISNA, in Persian)

- ISNA interview with Mohsen Hashemi Rafsanjani about the Rafsanjani family (in Persian)

- Friday Sermon at Tehran University: We Will Soon Join The Nuclear Club — For Peaceful Purposes (video clip from 3 December 2004)

- Video Archive of Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani

- "The U.S. and Iran" by George Church

- Arms for Hostage Deals

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Hashem Sabbaghian |

Minister of Interior 1979–1980 |

Succeeded by Mohammad-Reza Mahdavi Kani |

| Vacant Title last held by Javad Saeed |

Chairman of the Parliament 1980–1989 |

Succeeded by Mehdi Karroubi |

| Preceded by Ali Khamenei |

President of Iran 1989–1997 |

Succeeded by Mohammad Khatami |

| Chairman of the Expediency Council 1989–present |

Incumbent | |

| Preceded by Ali Meshkini |

Chairman of the Assembly of Experts 2007–2011 |

Succeeded by Mohammad-Reza Mahdavi Kani |

| Military offices | ||

| Vacant | Deputy of Commander-in-Chief of the Iranian Armed Forces 1988–1989 |

Vacant |

| Assembly seats | ||

| Preceded by Fakhreddin Hejazi |

First deputy of Tehran, Rey, Shemiranat and Eslamshahr 1984, 1988 |

Succeeded by Ali-Akbar Mousavi Hosseini |

.jpg)