Radio personality

A radio personality is a person who has an on-air position in radio broadcasting. A radio personality that hosts a radio show is also known as a radio host, and in India and Pakistan as a radio jockey. Radio personalities who introduced and played individual selections of recorded music were originally known as disc jockeys before the term evolved to describe a person who mixes a continuous flow of recorded music in real time. Broadcast radio personalities may include Talk radio hosts, AM/FM radio show hosts, and Satellite radio program hosts. Notable radio personalities include pop music radio hosts Martin Block, Alan Freed, Dick Clark, Wolfman Jack, and Casey Kasem, shock jock's such as Howard Stern, as well as sports talk hosts such as Mike Francesa and political talk hosts such as Rush Limbaugh.

Description

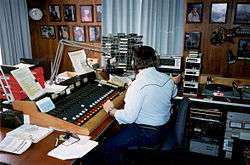

A radio personality can be someone who introduces and discusses genres of music; hosts a talk radio show that may take calls from listeners; interviews celebrities or guests; or gives news, weather, sports, or traffic information. The radio personality may broadcast live or use voice-tracking techniques.[1]

Increasingly, radio personalities are expected to supplement their on-air work by posting information online, such as on a blog. This may be either to generate additional revenue or connect with listeners.[2]

With the exception of small or rural radio stations, much of music radio broadcasting is now accomplished by broadcast automation, a computer-controlled playlist airing MP3 audio files which contain the entire program consisting of music, commercials, and a radio announcer's pre-recorded comments.

Radio disc jockey history

In the past, the term "disc jockey" was exclusively used to describe on-air personalities who played recorded music and hosted radio shows that featured popular music. [3] Unlike the modern club DJ who uses beatmatching to mix transitions between songs to create continuous play, radio DJs played individual songs or music tracks while voicing announcements, introductions, comments, jokes, and commercials in between each song or short series of songs.[4] During the 1950s, 60s and 70s, radio DJs exerted considerable influence on popular music, especially during the Top 40 radio era, because of their ability to introduce new music to the radio audience and promote or control which songs would be given airplay.[5][6]

1900s to 1950s

In 1892, Emile Berliner began commercial production of his gramophone records, the first disc records to be offered to the public. The earliest broadcasts of recorded music were made by radio engineers and experimenters. On Christmas Eve 1906, American Reginald A. Fessenden broadcast both live and recorded music from Brant Rock, Massachusetts. In 1907, American inventor Lee DeForest broadcast a recording of the William Tell Overture from his laboratory in the Parker Building in New York City, claiming "Of course, there weren't many receivers in those days, but I was the first disc jockey".[5]

Ray Newby, of Stockton, California claimed on a 1965 episode of CBS I've Got a Secret to be regularly playing records on a small transmitter while a student at Herrold College of Engineering and Wireless in San Jose, California in 1909.[7][8]

By 1910, radio broadcasters had started to use "live" orchestras as well as prerecorded sound. In the early radio age, content typically included comedy, drama, news, music, and sports reporting. Most radio stations had an orchestra or band on the payroll.[9][10] The Federal Communications Commission also clearly favored live music, providing accelerated license approval to stations promising not to use any recordings for their first three years on the air.[11] Many noted recording artists tried to keep their recorded works off the air by having their records labeled as not being legal for airplay.[12] It took a Federal court ruling in 1940 to establish that a recording artist had no legal right to control the use of a record after it was sold.[11]

Elman B. Meyers started broadcasting a daily program in New York City in 1911 consisting mostly of recorded music. In 1914 his wife Sybil True broadcast records borrowed from a local music store. The first British DJ was Christopher Stone, who in 1927 convinced the BBC to let him broadcast a program consisting of American and American-influenced jazz records interspersed with his ad libbed introductions.[13]

In 1935, American radio commentator Walter Winchell coined the term "disc jockey" (the combination of disc, referring to the disc records, and jockey, which is an operator of a machine) as a description of radio announcer Martin Block, the first announcer to become a star. While his audience was awaiting developments in the Lindbergh kidnapping, Block played records and created the illusion that he was broadcasting from a ballroom, with the nation’s top dance bands performing live. The show, which he called Make Believe Ballroom, was an instant hit.[11]

Block was notable for his considerable influence on a records popularity. Block's program on station WNEW was highly successful, and Block was described as "the make-all, break-all of records. If he played something, it was a hit". Block later negotiated a multimillion-dollar contract with ABC for a syndicated nationwide radio show.[13]

The earliest printed use of the term "disc jockey" appeared on August 13, 1941 when Variety published "... Gilbert is a disc jockey, who sings with his records." By the end of World War II, disc jockeys had established a reputation as "hitmakers", someone who's influence "could start an artist's career overnight". [13]

Disputes with the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers (ASCAP) and the American Federation of Musicians (AFM) affected radio DJs during World War II. ASCAP and AFM cited the decline in demand for live appearances of musical artists due to the proliferation of radio disc jockeys playing recorded music. The disputes were settled in 1944.[14]

1950s to present

The postwar period coincided with the rise of the radio disc jockey as a celebrity separate from the radio station, also known as a "radio personality". In the days before station-controlled playlists, the DJ often followed their personal tastes in music selection. DJs also played a role in exposing rock and roll artists to large, national audiences. While at WERE (1300 AM) in Cleveland, Ohio, DJ Bill Randle was one of the first to introduce Elvis Presley to radio audiences in the northeastern U.S.[15]

Notable U.S. radio disc jockeys of the period include Alan Freed, Wolfman Jack, Casey Kasem,[16] and their British counterparts such as the BBC's Brian Matthew and Alan Freeman, Radio London's John Peel, Radio Caroline's Tony Blackburn, and Radio Luxembourg's Jimmy Savile.[17][18]

Alan Freed is commonly referred to as the "father of rock and roll" due to his promotion of the music and his introduction of the term rock and roll on radio in the early 1950s. Freed also made a practice of presenting music by African-American artists rather than cover versions by white artists on his radio program. Freed's career ended when it was shown that he had accepted payola, a practice that was highly controversial at the time, resulting in his being fired from his job at WABC.[19]

A number of actors and media personalities began their careers as traditional radio disc jockeys who played and introduced records, such as Hogan's Heroes star Bob Crane, talk show host Art Bell, American Idol host Ryan Seacrest, and Howard Stern.[20]

Radio DJs often acted as commercial brokers for their program and actively solicited paying sponsors. They could also negotiate which sponsors would appear on their program. Many wrote and delivered the commercials themselves, talking the place of advertising agencies who formerly executed these responsibilities.[21]

Radio disc jockey programs were often syndicated, at first with hourly musical programs with entertainers such as Dick Powell and Peggy Lee acting as radio DJs introducing music and providing continuity and commentary, [22] and later with radio personalities such as Casey Kasem who hosted the first nationally-syndicated Top 40 countdown show.[23]

Wartime radio DJs

During World War II, disc jockey programs such as GI Jive were broadcast by the U.S. Armed Forces Radio Service to troops. GI Jive initially featured one of a series of guest DJs for each broadcast who would introduce and play popular recordings of the day; some were civilian celebrities, while others were servicemen. In May 1943, however, the format settled on a single regular host DJ, Martha Wilkerson, who was known on the air as "GI Jill." [24][25][26] Axis powers radio broadcasts aimed at Allied troops also adopted the disc jockey format, featuring personalities such as Tokyo Rose and Axis Sally who played popular American recorded songs interspersed with propaganda.

During the Vietnam War, United States Air Force sergeant Adrian Cronauer was a notable Armed Forces Radio disc jockey whose experiences later inspired the 1987 film Good Morning, Vietnam starring Robin Williams as Cronauer.[27][28]

Cold War radio DJ Willis Conover's program on the Voice of America from 1955 through the mid-1990s featured jazz and other "prohibited" American music aimed at listeners in the Soviet Union and other Communist countries. Conover reportedly had "millions of devoted followers in Eastern Europe alone; his worldwide audience in his heyday has been estimated at up to 30 million people".[29]

African American disc jockeys

African American radio DJs emerged in the mid 1930s and late 1940s, mostly in cities with large black populations such as New York, Chicago, Los Angeles and Detroit. Jack L. Cooper was on the air 91⁄2 hours each week on Chicago's WCAP and is credited with being one of the first black radio announcers to broadcast gramophone records, including gospel music and jazz, using his own phonograph.[30]

Other prominent DJs included Al Benson on WGES in Chicago, who was the first popular disc jockey to play urban blues and use "black street slang" in his broadcasts, and Jesse "Spider" Burke on KXLW in Saint Louis, James Early on WROX (AM) in Clarkesdale, as well as Ramon Bruce on WHAT (AM) in Philadelphia. Most major U.S. cities operated a full-time rhythm and blues radio station, and as African Americans traveled the country they would spread the word of their favorite radio personalities.[31]

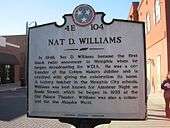

Nat D. Williams was the first African American disc jockey on WDIA in Memphis with his popular Tan Town Jamboree show. African American radio DJs found it necessary to organize in order to gain opportunities in the radio industry, and in the 1950s formed the National Jazz, Rhythm and Blues Disc Jockey Association. The group's name was later changed to the National Association of Radio and Television Announcers. In 1960, radio station managers formed the Negro Radio Association to foster and develop programming and talent in the radio broadcasting industry.[32][31]

Payola scandal

Especially during the 1950s, the sales success of any record depended to a large extent on its airplay by popular radio disc jockeys.[14] The illegal practice of payment or other inducement by record companies for the radio broadcast of recordings on commercial radio in which the song is presented by a DJ as being part of the normal day's broadcast became known in the music industry as "payola". The first major United States Senate payola investigation occurred in 1959. Nationally renowned DJ Alan Freed, who was uncooperative in committee hearings, was fired as a result. DJ Dick Clark also testified before the committee, but survived, partially due to the fact that he had previously divested himself of ownership interest in all of his music-industry holdings.[33]

After the initial investigation, radio DJs were stripped of the authority to make programming decisions, and payola became a misdemeanor offense. Programming decisions became the responsibility of station program directors. As a result, the process of persuading stations to play certain songs was simplified. Instead of reaching numerous DJs, record labels only had to connect with one station program director. Labels turned to independent promoters to circumvent allegations of payola.[34]

Format changes

As radio stations moved from the AM Top 40 format to the FM album-oriented rock format or adopted more profitable programming such as news and call-in talk shows, the impact of the radio DJ on popular music was lessened. The emergence of shock jock personalities and morning zoo formats saw the DJs role change from music host to cultural provocateur and comedian.[35]

From the late 50s to the late 1980s when the Top 40 music radio format was popular, audience measuring tools such as ratings diaries were used. However a combination of financial pressures and new technology such as voice tracking and the Portable People Meter (PPM) began to have negative effects on the role of radio DJs beginning in the late 1990s, prompting one radio program manager to comment, "There was a time when the “top 40” format was ruled by legends such as Casey Kasem, or Wolfman Jack, and others who were known for both playing the hits and talking to you. Now with PPMs, it is all about the music, commercials and the format."[36] Such format changes as well as the rise of new music distribution models such as MP3 and online music stores led to the demise of radio DJs reputation as trendsetters and "hit makers" who wielded considerable influence over popular music.[5][6]

Types of radio personalities

- FM/AM radio - AM/FM personalities play music, talk, or both.[37] Some examples are Opie and Anthony, Howard Stern, Elvis Duran, Big Boy, Kidd Kraddick, John Boy and Billy, The Bob and Tom Show, and Rickey Smiley.

- Talk radio - Talk radio personalities often discuss social and political issues from a particular political point of view.[37] Some examples are Rush Limbaugh, Art Bell, George Noory, Brian Kilmeade, Brian Lehrer, Don Geronimo and John Gibson.

- Sports talk radio - Sports talk radio personalities are often former athletes, sports writers, or television anchors and discuss sports news.[37] Some examples are Dan Patrick, Tony Kornheiser, Colin Cowherd, Mike Francesa and Chris Russo.

- Satellite radio - Satellite radio personalities are not subject to government broadcast regulations and are allowed to play explicit music.[37]

Salary in the US

Radio personality salaries are influenced by years of experience and education. In 2013, the median salary of a radio personality in the US was $28,400.

- 1–4 years: $15,200-39,400,

- 5–9 years: $20,600-41,700,

- 10–19 years: $23,200-51,200,

- 20 or more years: $26,300-73,000.

A radio personality with a bachelor's degree had a salary range of $19,600-60,400.[38]

The salary of a local radio personality will differ from a national radio personality. National personality pay can be in the millions because of the increased audience size and corporate sponsorship. For example, Rush Limbaugh was reportedly paid $40 million annually as part of the eight-year $400 million contract he signed with Clear Channel Communications.[39]

Career opportunities

Due to a radio personality's vocal training, opportunity to expand their career often exist. Over time a radio personality could be paid to do voice overs for commercials, television shows, and movies.[40]

Training

Universities offer classes in radio broadcasting and have a radio station, where students can obtain on-the-job training and course credit.[41] Prospective radio personalities can also intern at radio stations for hands-on training from professionals. Training courses are also available online.[41]

Education

Some radio personalities do not have a formal education, but many hold degrees in audio engineering.[42] Radio personality typically have a bachelor's in radio-television-film, mass communications, journalism, or English.[43]

Job requirements

A radio personality position generally has the following requirements:[44][45]

- Good clear voice with excellent tone and modulation

- Great communication skills and creativity to interact with listeners

- Knowledgeable on current affairs and social trends

- Thinking outside the box

- Ability to develop their own style

- A good sense of humor

See also

References

- ↑ L. A. Heberlein - The Rough Guide to Internet Radio 2002 - Page v. "In addition to putting songs together, a good radio host can tell you things you didn't know about the artists, the songs, and the times."

- ↑ Rooke, Barry; Odame, Helen Hambly (2013). ""I Have to Blog a Blog Too?" Radio Jocks and Online Blogging". Journal of Radio & Audio Media. 20 (1): 35. doi:10.1080/19376529.2013.777342.

- ↑ Shelly Field (21 April 2010). Career Opportunities in Radio. Infobase Publishing. pp. 2–. ISBN 978-1-4381-1084-4.

- ↑ Higgins, Terry. "Club Features New Breed of Disc Jockey". Milwaukee Sentinel. Milwaukee Sentinel, June 29,1984. Retrieved 7 July 2016.

- 1 2 3 Udovitch, Mim. "Last Night a DJ Saved My Life The History of the Disc Jockey By BILL BREWSTER and FRANK BROUGHTON Grove Press". New York Times Book Review. New York Times Company. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- 1 2 Battaglio, Stephen. "Television/Radio; When AM Ruled Music, and WABC Was King". New York Times. New York Times Company. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- ↑ Ray Newby appearance on CBS' I've Got a Secret, 27 September 1965. Secret listed as: "'I was the world's first radio disc jockey' (in 1909)." Rebroadcast on the Game Show Network on 22 May 2008.

- ↑ Bay Area Radio Museum. "Doc Herrold and Ray Newby". Retrieved 21 May 2008.

- ↑ Roddy, Bill. "NBC's Radio City, San Francisco". Roddy, Bill. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- ↑ Samuels, Rich. "The NBC Chicago Orchestra". Samuels, Rich. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- 1 2 3 Fisher, Marc. Something in the Air. Random House. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-375-50907-0.

- ↑ "Keep Your Big Mouth Shut ..Disc Jockeys Learn To Toil And Spin". Eugene Register-Guard. 23 June 1955. Retrieved 29 December 2013.

- 1 2 3 Brewster, Bill; Broughton, Frank. "Last Night a DJ Saved My Life - The History of the Disc Jockey". New York Times. The New York Times Company. Retrieved 8 September 2015.

- 1 2 "Disc jockey - Radio personality". Encyclopedia Britannica. britannica.com. Retrieved 6 July 2016.

- ↑ Curtis, James M. (1987). Rock eras: interpretations of music and society, 1954-1984. Popular Press. ISBN 978-0-87972-369-9.

- ↑ Richard Sisson; Christian K. Zacher; Andrew Robert Lee Cayton (2007). The American Midwest: an interpretive encyclopedia. Indiana University Press. pp. 636–. ISBN 978-0-253-34886-9. Retrieved 13 October 2011.

- ↑ Christopher H. Sterling; Michael C. Keith; Communications Museum of Broadcast (2004). Encyclopedia of radio. Taylor & Francis. pp. 375–. ISBN 978-1-57958-249-4. Retrieved 13 October 2011.

- ↑ "Big Day Belongs To The Local Hero". The Glasgow Herald. 12 September 1983. Retrieved 29 December 2013.

- ↑ Glenn C. Altschuler (16 July 2003). All shook up: how rock 'n' roll changed America. Oxford University Press. pp. 152–. ISBN 978-0-19-513943-3. Retrieved 13 October 2011.

- ↑ Peyton Paxson (January 2003). Media Literacy: Thinking Critically about Music & Media. Walch Publishing. pp. 28–. ISBN 978-0-8251-4487-5.

- ↑ Alexander Russo (20 January 2010). Points on the Dial: Golden Age Radio beyond the Networks. Duke University Press. pp. 165–. ISBN 0-8223-9112-0.

- ↑ Margaret A. Blanchard (19 December 2013). History of the Mass Media in the United States: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 569–. ISBN 978-1-135-91742-5.

- ↑ Christopher H. Sterling (13 May 2013). Biographical Encyclopedia of American Radio. Routledge. pp. 207–. ISBN 978-1-136-99375-6.

- ↑ The Directory of the Armed Forces Radio Service Series. Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-30812-8

- ↑ Mackenzie, Harry (1999). The Directory of the Armed Forces Radio Service Series. Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-30812-8

- ↑ Bivins, Tom. World War II on the Radio. J387:Communication History document. University of Oregon.

- ↑ Jim Barthold (March 1, 2005), The real life of Adrian Cronauer, Urgent Communications, archived from the original on 2012-05-09, retrieved 2013-01-13

- ↑ Adrian Cronauer: Air Force Radio Announcer in Vietnam at HistoryNet.com

- ↑ Freund, Charles Paul. "The DJ Who Shook the Soviet Union With Jazz". Newsweek. Newsweek. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- ↑ "Chicago's Radio Voice, Jack Cooper", at African American Registry. Retrieved 20 May 2014

- 1 2 Christopher H. Sterling (1 March 2004). Encyclopedia of Radio 3-Volume Set. Routledge. pp. 45–. ISBN 978-1-135-45649-8.

- ↑ William Barlow (1999). Voice Over: The Making of Black Radio. Temple University Press. pp. 97–. ISBN 978-1-56639-667-7.

- ↑ "Dick Clark survives the Payola Scandal". history.com.

- ↑ Cartwright, Robin (August 31, 2004). "What's the story on the radio payola scandal of the 1950s?." The Straight Dope.

- ↑ Laurence Etling (19 July 2011). Radio in the Movies: A History and Filmography, 1926-2010. McFarland. pp. 4–. ISBN 978-0-7864-8616-8.

- ↑ McKay, Jeff. "The State of the Disc Jockey". Radio Info. radioinfo.com. Retrieved 7 July 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 "Radio and Television Job Description". CareerPlanner.com. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

- ↑ "Disc Jockey (DJ), Radio Salary, Average Salaries". Payscale.com. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- ↑ "Rush Limbaugh Net Worth". celebritynetworth.com. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

- ↑ "Radio Jockey: Job Prospects & Career Options". webindia123.com. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

- 1 2 "ASU Dept. of Radio-TV". Arkansas State University. Retrieved 5 March 2013.

- ↑ "Radio Jockey Education and Job requirements". educationrequirements.org. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ↑ "Announcers". bls.gov. 8 January 2014.

- ↑ "Radio Jockey education and job requirements". educationrequirements.org. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ↑ "RJs Talk About Their Careers in Radio". YouCareer.in. 1 September 2013. Retrieved 28 October 2015.