Radosław Sikorski

| Radosław Sikorski | |

|---|---|

| |

| Marshal of the Sejm | |

|

In office 24 September 2014 – 23 June 2015 | |

| President | Bronisław Komorowski |

| Preceded by | Ewa Kopacz |

| Succeeded by | Małgorzata Kidawa-Błońska |

| Minister of Foreign Affairs | |

|

In office 16 November 2007 – 22 September 2014 | |

| Prime Minister | Donald Tusk |

| Preceded by | Anna Fotyga |

| Succeeded by | Grzegorz Schetyna |

| Minister of National Defence | |

|

In office 31 October 2005 – 7 February 2007 | |

| Prime Minister |

Kazimierz Marcinkiewicz Jarosław Kaczyński |

| Preceded by | Jerzy Szmajdziński |

| Succeeded by | Aleksander Szczygło |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Radosław Tomasz Sikorski 23 February 1963 Bydgoszcz, Poland |

| Political party | Civic Platform |

| Other political affiliations | Law and Justice (2005–2007) |

| Spouse(s) | Anne Applebaum (1992–present) |

| Children |

Aleksander Tadeusz |

| Alma mater | Pembroke College, Oxford |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

| Signature |

|

Radosław Tomasz "Radek" Sikorski ([raˈdɔswaf ɕiˈkɔrskʲi]; born 23 February 1963) is a Polish politician and journalist. He was Marshal of the Sejm from 2014 to 2015 and Minister of Foreign Affairs in Donald Tusk's cabinet between 2007 and 2014. He previously served as Deputy Minister of National Defense (1992) in Jan Olszewski's cabinet, Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs (1998–2001) in Jerzy Buzek's cabinet and Minister of National Defense (2005–2007) in Kazimierz Marcinkiewicz and Jarosław Kaczyński's cabinets.

Early life and education

Sikorski was born in Bydgoszcz. He chaired the student strike committee in Bydgoszcz in March 1981 while studying at the I Liceum Ogólnokształcące (High School).[1] In June 1981 he travelled to the United Kingdom to study English. After martial law was declared in December 1981, he was granted political asylum in Britain in 1982.[2] He studied Philosophy, Politics and Economics at Pembroke College, University of Oxford, where Zbigniew Pełczyński was one of his tutors.[3]

During his time at Oxford, Sikorski was head of the Standing Committee of the debating society, the Oxford Union (where he organised debates on martial law), president of the Oxford University Polish Society, member of the Canning Club,[4] and was elected to the Bullingdon Club, a dining society that counted among its members former British Prime Minister, David Cameron, former Chancellor George Osborne, and current Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson.[5] His articles were published in prestigious Polish émigré magazines – the Paris-based Kultura and Zeszyty Historyczne as well as Britain's Sunday Telegraph and Tatler magazines.[6][7] He graduated in 1986.

In 1987, Sikorski was awarded British citizenship, which he renounced in 2006 on becoming Minister of Defense of Poland.[8]

Career

In the mid-1980s, Sikorski worked as a freelance journalist for publications such as The Spectator and The Observer. He also wrote for the Indian newspaper The Statesman of Kolkata In 1986, he travelled in Afghanistan, as he stated in his book, "to write about the war the mujahideen were waging against the Soviet Union". While a war correspondent for The Sunday Telegraph, he brought out the first report and photographs of the US Stinger missiles, whose use was a turning point in the war.[9][10] In 1987, he made a hundred-day journey, under Soviet bombardment, to the ancient city of Herat. He won the World Press Photo award in 1988 for a photograph of a family killed and mummified in their home as a result of communist bombing raid.[11] His adventures were presented in the documentary "Polish Mujahideen: Radosław Sikorski", produced by Discovery Channel. Sikorski described his perilous journey to Herat in his first book "Dust of the Saints: A Journey to Herat in Time of War".[12] In 1989, he became the chief foreign correspondent for the American conservative magazine National Review, reporting from Afghanistan and Angola. He received praise for his article published in January 1989, The coming crack-up of Communism, which proved prophetic.[13] His article describing an ambush on the Benguela Highway conducted by Jonas Savimbi's UNITA rebels attracted widespread interest.[14]

In 1990–91, he was the Sunday Telegraph's Warsaw correspondent. He was the author of the 'Interview of the Month' program on Polish public TV, in which he interviewed Margaret Thatcher, Lech Walesa, Vaclav Klaus, Otto von Hapsburg, Henry Kissinger, Qian Qichen and others.[15]

Deputy minister in Olszewski and Buzek governments

Sikorski returned to Poland in August 1989. He briefly served as deputy defence minister in the Jan Olszewski government in 1992, in which he helped launch the Polish bid to join NATO.

From 1998 to 2001, Sikorski served as undersecretary of state at the ministry of foreign affairs in the Jerzy Buzek's government, being deputy first to Bronisław Geremek, and then to Władysław Bartoszewski. He oversaw the consular service and initiated reforms of services for Poles abroad.[16] He signed agreements to abolish visas with countries in Asia, Africa and Latin America, Singapore and Israel among them. He was Honorary Chairman of the Foundation for Assistance to Poles in the East.[17]

During his time as a Deputy Foreign Minister, Sikorski focused on reforms inside the Ministry and started the campaign to protest the use of the misleading term "Polish concetration camps" in western media. He introduced the "cheap visa" program for Poland's Eastern neighbors and started the recovery of post-Soviet properties in Warsaw. He introduced competitions for posts of heads of Polish Institutes abroad.[16]

When Ted Turner made a demeaning joke about Poles in a Washington speech, Sikorski demanded an apology and Turner complied.[18] Sikorski's appeal to Polish nationals with dual citizenship to use the passport of the country they were visiting caused some controversy among the Polish expatriate community, but has now become an established practice.[19]

In the United States

From 2002 to 2005, Sikorski was a resident fellow of the American Enterprise Institute in Washington, D.C., and executive director of the New Atlantic Initiative.[20] He was editor of the analytical publication European Outlook. He organised international conferences, including the "Ronald Reagan - Legacy for Europe[21]" in 2003, during which prominent politicians from Eastern Europe discussed the impact American president left on the world. Other major conferences included: "25th Anniversary of the birth of Solidarity",[22] "Axis of Evil: Belarus - The Missing Link"[23] and "Ukraine's Choice" at the time of the Orange Revolution.[24]

Senator and Minister of Defence

In 2005 Sikorski returned to Poland and was elected senator from his home town of Bydgoszcz with 76,370 votes.[25] He joined Prime Minister Marcinkiewicz's government as Minister of National Defence on the 31 October.

During his time in MoD, he moved Warsaw Pact-era files to the Institute of National Remembrance, declassified Warsaw Pact maps which demonstrated Soviet plans to use nuclear weapons in an offensive war against NATO[26] and cancelled the military pension of Helena Brus, a Stalinist prosecutor who sentenced the anti-communist Polish resistance general August Emil "Nil" Fieldorf to death.[27] He introduced electronic auctions in procurement for defense equipment, saving the ministry a great amount of money.[28] He announced the tender to buy a fleet of new jets for government transportation.[29] He declassified a file of an operation codenamed "Szpak" (starling) by the Military Information Services (Wojskowe Służby Informacyjne, WSI) which documented their operations against him containing transcripts of the bugging of his home and telephone as well as hostile articles in the media inspired by WSI operatives.[30]

He resigned on 5 February 2007, on the eve of Poland's engagement in the war in Afghanistan in protest against the activities of the chief of military intelligence, Antoni Macierewicz.[31] Though never a member of the Law and Justice party, he served out the parliamentary term in the Law and Justice Senatorial Club. In the early parliamentary elections of 2007, he was elected to the Lower House (Sejm) with 117,291 votes, one of 10 best results in the country.[32]

Minister of Foreign Affairs

.jpg)

He was sworn in as Minister of Foreign Affairs in Donald Tusk's government on 16 November 2007.[33] He joined the Civic Platform party and became a member of its national board in 2008.[34]

Sikorski's policies are best understood in his exposes, his annual statement to Parliament. Each one was followed by a day-long debate.[35]

As Minister of Foreign Affairs, Sikorski normalized relations with Russia, and helped to terminate the Russian embargo on Polish agricultural products.[36] In 2009, Sikorski said that Russia is needed to solve the problems of European and global theatre. Therefore, if Russia could fulfill the conditions, it could apply to join NATO. He restated that NATO's criteria that Russia would have to meet are: be a democratic state, have civilian control over the army, and to settle any territorial disputes with its neighbors.[37] At the same time, he enhanced relations with Germany and France. Cooperation in the Weimar Triangle –Poland, Germany, France - was particularly intense during his term of office.[38] Weimar Triangle meetings included consultations with third parties, such as Ukraine, Moldova and Russia.

As foreign minister, he turned the ministry into a global institution with 4500 employees and 100 foreign branches. Over seven years his ministry carried out various reforms, introducing the Diplomatic Security Service, global digital secure communications, ISO standards in procedures, electronic document management, a blackberry and laptop for every diplomat, a satellite phone for every posting, new visual standards book; The Foreign Service Day, a dress code, the Bene Merito medal,[39] The Polish Institute of Diplomacy, Poland's Lech Wałęsa Solidarity Prize[40] (worth 1 mln EUR); reduced the number of chancelleries in the MFA HQ from over 30 to 2, reformed the telegram and courier systems, reduced employment while raising salaries; quadrupled ambassadors and consuls operational funds, closed down 30 embassies and consulates and opened several new ones;[41] he opened a Polish consulate in Sevastopol, the only one representing a Western country in that city for 4 years; built a new EU embassy in Brussels,[42] a new Embassy residence in Washington, DC,[43] a new Consulate-General in London;[44] he moved consulates in Cologne, Manchester and Madrid; he created the MFA committee on cyber defence; the European Endowment for Democracy, authorized intelligence operations.[45][46]

During Sikorski's term in office he was a regular visitor in Moscow and his Russian counterpart Foreign Minister, Sergei Lavrov visited Warsaw regularly.[47][48][49] Sikorski made his first visit in Moscow in 2008 with Donald Tusk. In 2009 he visited Moscow to enhance Polish-Russian cooperation.[50] During one of Lavrov visits, he engaged in Q&A session with Polish diplomats during MFA annual global ambassadors conference.[51]

In 2008, Sikorski concluded a long negotiation with the US over the siting of a missile defense base in Poland. He insisted on Polish jurisdiction over base personnel and asked the US to enhance Poland's air defenses as part of the deal. The agreement was finally signed with the U.S. Secretary of State, Condoleezza Rice, over the objections of Russia.[52] The agreement came less than two weeks after the outbreak of the 2008 Russo-Georgian South Ossetian war.[53] On 17 September 2009 the Obama administration changed the plans for the base.[54] The annex to the agreement, which envisages shorter range missiles capable of defending Poland's territory was signed in the presence of Sikorski and Secretary of State, Hillary Clinton on 3 June 2010 in Kraków.[55]

In March 2010, Sikorski took part in the Civic Platform Presidential primaries against the then Parliamentary Speaker, Bronisław Komorowski, who went on to be elected President. At that time, Sikorski enjoyed some of the highest approval and trust ratings among Polish politicians.[56]

At the height of the European sovereign debt crisis in November 2011 Sikorski delivered a speech in Berlin: "Poland and the future of the European Union" in front of the German Council on Foreign Relations, the prestigious non-profit organization composed of the German foreign policy elite.[57] He warned that EU member states faced a choice "between deeper economic integration or collapse of the Eurozone". Sikorski made an extraordinary appeal: I will probably be the first Polish foreign minister in history to say so, but here it is: I fear German power less than I am beginning to fear German inactivity. Sikorski labelled Germany Europe's "indispensable nation" and appealed to Germany to lead in saving the euro, offering Poland's support. According to many political commentators and journalists, this speech made a tremendous impact on German and European politics, not least because it changed the perception of Poland: from a problematic and needy recipient of Western support, to a full-fledged member of the European Union.[58][59]

Sikorski was involved in the events of the winter 2014 Ukraine Euromaidan protests at the international level. He signed on 21 February along with Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovich and opposition leaders Vitaly Klitchko, Arseniy Yatsenyuk, and Oleg Tyagnibok as well as the Foreign Ministers of Russia, France and Germany a memorandum of understanding to promote peaceful changes in Ukrainian power.[60]

European Union foreign policy campaign

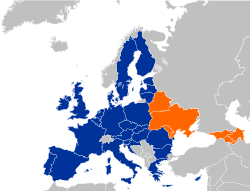

As Poland's Minister of Foreign Affairs, Sikorski was a strong supporter of closer ties with the EU's Eastern Neighbors. He opted for the integration of those countries into European structures, advocated anchoring Ukraine within the European Union[61] and called for economic changes in Belarus.[62]

Sikorski was the main architect, along with his Swedish counterpart and friend Carl Bildt, of the eastern policy of the EU – which came to be called the Eastern Partnership.[63]

Sikorski was also a supporter of the opening of EU borders to Ukraine and the Russian exclave of Kaliningrad by means of Local Border Traffic (LBT) agreements. Thanks to those agreements, citizens of neighboring regions may travel visa-free in Poland.[64] The agreement with Russia was signed by Sikorski and the Foreign Minister of Russia, Sergey Lavrov, on 14 December 2011.[65] It entered into force in July 2012 and has been kept in place despite worsening of relations in other areas.

On 19 February 2014, Sikorski was requested by the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, Catherine Ashton, to begin a diplomatic mission in Kiev.[66] On 16 July, shortly after publicly accusing Russia of strengthening support for separatist rebels in Ukraine and a Ukrainian military transport plane shootdown, and shortly before an EU summit on whether to impose sanctions on Russia, Sikorski flew to Kiev to meet with Ukraine's Foreign Minister, Pavlo Klimkin.[67][68]

Sikorski was the leading European politician during the Maidan crisis in February 2014, which was sparked by refusal of signing the EU-Ukraine Association Agreement by Yanukovich.[69]

On 19 February 2014, Sikorski, with the support of the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, Catherine Ashton, launched a diplomatic mission in Kiev.[70] It resulted in the signing, on February 21 by Sikorski, Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovich and opposition leaders Vitaly Klitchko, Arseniy Yatsenyuk, and Oleg Tyagnibok as well as the Foreign Ministers of France and Germany an agreement to constitutional rule and promote peaceful reforms in Ukraine. Following speeches by Sikorski and Frank-Walter Steinmeier the agreement was approved by the Maidan Rada with a vote of 35:2. The next day Yanukovich fled Kiev.[71]

On 16 July 2014, shortly after publicly accusing Russia of supporting for separatist rebels in Ukraine, and shortly before an EU summit on whether to impose sanctions on Russia, Sikorski flew to Kiev to meet with Ukraine's Foreign Minister, Pavlo Klimkin, where he argued that sanctions should be imposed on Russia.[72][73]

On 1 August 2014, Sikorski was nominated for the post of EU's High Representative. Sikorski had been a strong supporter of sanctions against Russia, in contrast to his top opponent for the position, Federica Mogherini.

On 3 August, Sikorski told CNN's Fareed Zakaria that the Malaysia Airlines Flight 17 crash had helped bring European leaders together against Russia. He noted the sanctions will cause economic "losses all around", especially for Poland, but declared that Europe cannot "stand idly by when Russia annexes, for the first time since the Second World War, a neighbor's province. And now supplying sophisticated weaponry to the separatists. "He called for more NATO troops in Poland and prepositioning of its equipment, as well as standing defense plans and bigger response forces.

On 30 August, Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk, was appointed President of the European Council.

When later questioned, Sikorski called it "undoubtedly the prime minister's personal success but equally a success of Poland. We take this decision as both a signal of appreciation of the policies Poland has pursued over ten years of its EU membership and a sign that the distinctions between 'old' and 'new' member states are rapidly crumbling. On the 10th anniversary of Poland's accession to the EU, a Pole will lead the institution which sets the priorities of Europe."[74]

One such priority, according to Sikorski, is "a well interconnected network of energy infrastructure and more efficient security of supply mechanisms."[74] He backed Tusk's proposed pan-European "Energy Union" plan.[75]

In September 2015, after leaving the Foreign Ministry, Sikorski again visited Kiev, arguing that if Russia moves further into Ukraine, the West should provide it with defensive weapons.[76]

Marshal of the Sejm

On 24 September 2014, Sikorski was elected Marshal of the Sejm. As Marshal, Sikorski introduced a series of reforms: new standards for parliamentary travel, streamlined voting procedures and a new visual standard for parliamentary documents. He also authorized the construction of a new building for Parliamentary Committees.[77]

On 10 June 2015 Sikorski announced his resignation from the post in the wake of an illegal wiretaps scandal. Despite being the victim of illegal action by others, Sikorski explained that he did not want to damage Civic Platform's chances of success in the forthcoming election - "I made this decision for the sake of the Civic Platform, the only party that can maintain Poland's high position in the world".[78]

On 23 June 2015 Sikorski officially resigned. He decided not to run again for parliament.

Current Activities

On 6 November 2015 Sikorski was appointed a Senior Fellow at Harvard University's Center for European Studies.[79]

On 11 February 2016, Sikorski was elected the Chairman of the Board of the Bydgoszcz Industrial-Technological Park. He has donated his salary to Bydgoski Care and Education Institutions Unit (Bydgoski Zespół Placówek Opiekuńczo-Wychowawczych).[80]

Controversy

Sikorski received much attention from the tabloid media. Particularly notorious was "pizzagate" which resulted from a paparazzo photograph of the delivery of a large pizza by his security to his house where he was working all weekend over government papers.[81]

In 2012 a photographer demanded a fee for his photograph that Sikorski sent to his followers on Twitter without giving the source. Sikorski replied with congratulations and a pledge that his copyrights will be respected.[82] It subsequently turned out that the picture was a part of the Foreign Ministry's publicity campaign and the photographer got paid twice.

The Supreme Audit Office (NIK) alleged mismanagement in the MFA in the purchase of antique furniture. In fact, the furniture matching historic décor continues to serve Sikorski's successors.[83]

In Poland, Sikorski was criticized for trying to normalize relations with Russia, while abroad he is known for toughness on the Putin regime, criticizing the indolence of international institutions and demanding that they stand up against Russia's aggression, disinformation and corruption.

In 2014, Sikorski labeled pro-Russian separatists as "terrorists".[84] He also said: "Remember that on that Russian-Ukrainian border, people's identities are not as strong as we are used to in Europe. ... They reflect Ukraine's failure over the last 20 years and Ukraine's stagnant standards of living. You know, when you are a Ukrainian miner or soldier, and you earn half or a third of what your colleagues just across the border in Russia earn, that questions your identity."

Leaked conversations about Britain, America and Russia

In June 2014, a magazine in Poland published redacted transcripts of an illegally taped conversation between Sikorski and the former Polish finance minister Jacek Rostowski. The recordings were believed to have been made in the dining room of the Polish Business Council sometime between summer 2013 and spring 2014.[85][86] Sikorski is heard criticizing the British Prime Minister David Cameron for his handling of the EU's fiscal pact to appease Eurosceptics in the Conservative Party.[85][86][87]

Sikorski argued that the tapes, which did not contain any evidence of illegality, were part of an organized attack on the government: "The Government was attacked by an organized criminal group. We are not sure who is behind it, but I hope its members will be identified and punished".[88]

In another part of the leaked conversation, Sikorski was reported to have said: "The Polish-American alliance is worthless. It is even harmful because it creates a false sense of security for Poland".[89] Sikorski explained that his remarks were made at a time where there wasn't a single US soldier on Polish soil. Several parts of the conversation were subsequently cut and manipulated by journalists, as Sikorski proved using an un-edited transcript.[90]

In the fragment of the record Sikorski said: "We're going to antagonize Germany and Russia, and they will think that everything is ok because we have given a blowjob to the Americans. Losers. Total losers." Sikorski stated later that in the actual conversation, he was predicting what Polish foreign policy would look like under a Law and Justice government.[90]

Books published

Moscow's Afghan war. Soviet motives and western interests, 1987

Dust of the Saints, 1989 (the Polish translation, Prochy Świętych, was first published in 1990)

The Polish House: An Intimate History of Poland, 1998 (the American edition is titled Full Circle: A Homecoming to Free Poland)

Strefa Zdekomunizowana [Commie-free Zone], 2007

Awards and recognition

- Honorary Doctorate, Nova University, Lisbon[91]

- Badge of Merit to Culture (Odznaka Zasłużony Działacz Kultury; award for the promotion of culture)

- Wiktor 2006 award for 'most popular politician'[92]

- Freedom Award, the Atlantic Council[93]

- Ukrainian Order of Merit, first class (No. 407), 2007[94]

- Grand Officer, Legion of Honour, France[95]

- Lithuanian 'Millenium Star' medal, 2008[96]

- Maltese National Order of Merit, grade of 'Companion', 2009[97]

- Gold Badge of the Association of Poles in Lithuania, 2010[98]

- Commander Grand Cross of the Royal Order of the Polar Star of Sweden, 2011[99]

- Order of Prince Yaroslav the Wise, 3rd class – 2011, Ukraine

- Grand Officer's Cross, Order of the Crown, Belgium[100]

- Commander's Cross with Star, Order of Merit, Hungary[101]

- Order of Honour, Moldova[102]

- Medal "Merit for Polish Culture"

- Laurel of Skills and Competencies 2009 awarded by the Regional Chamber of Commerce in Katowice

- Passed among the "Top 100 Global Thinkers 2012" by the magazine Foreign Policy for "speaking the truth, even when it is not diplomatic."

- The Spectator and The Sunday Telegraph 'Young Writers' award.

Personal life

Sikorski is married to American journalist and historian, Anne Applebaum. They have two children, Aleksander (born 1997) and Tadeusz (2000). Sikorski rebuilt an old manor house in Chobielin, where he and his family now live.[103] The process of restoration, weaved with local history and reportage from the first years of independent Poland is described in his book, Full Circle: A Homecoming to Free Poland. During his early sojourn in Britain, Sikorski dated the actress Olivia Williams, who decades later would attend his 50th birthday party.[104]

See also

- History of Poland (1989–present)

- List of political parties in Poland

- List of politicians in Poland

- Politics of Poland

- Polish presidential election, 2005

- Polish parliamentary election, 2005

- Polish parliamentary election, 2007

- Polish parliamentary election, 2011

- Polish parliamentary election, 2015

References

- ↑ Radek Sikorski personal website

- ↑ Blair, David (25 January 2009). "Nato has 'no will' to admit Georgia or Ukraine". The Daily Telegraph. London.

- ↑ "Report" (PDF). Rhodes House. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- ↑ http://www.zyleta.net16.net/Zyla_Rados%C5%82aw_Sikorskions.php

- ↑ Thornhill, John; Cienski, Jan (23 May 2014). "Radoslaw Sikorski in the hot seat". ft.com. Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- ↑ Sikorski, Radosław (11.1984). "Uniwersytet Letni Polonii Świata" (PDF). Kultura Paryska. Instytut Literacki. Retrieved 06.05.2016. Check date values in:

|access-date=, |date=(help) - ↑ Sikorski, Radosław (1984). "A Man from Outside. Radek Sikorski interviews Norman Davies" (PDF). Kultura Paryska. Instytut Literacki. Retrieved 06.05.2016. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "Sikorski proves he renounced British citizenship".

- ↑ Odone, Cristina (10 March 2014). "'We cannot let Putin get away with this,' says Polish minister". Telegraph.co.uk. London.

- ↑ Sikorski, Radek (2 November 1986 (no. 1328)). "US missiles a big hit with Afghan rebels". Sunday Telegraph. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ "1988 Radek Sikorski SN1". World Press Photo. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ Sikorski, Radosław (1989). Dust of the Saints: A Journey to Herat in Time of War. London: Chatto & Windus. ISBN 9780701134365.

- ↑ "Decline or Fall?". National Review Online. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ Sikorski, Radosław (18 August 1989). "Inside Angola: the Mystique of Savimbi". National Review (61, no. 15).

- ↑ Warzecha, Łukasz (2007). Commie-free Zone: Extended Interview with Radosław Sikorski. Warsaw: AMF Plus Group. p. 102. ISBN 9788360532096.

- 1 2 Warzecha, Łukasz (2007). Commie-free Zone: Extended Interview with Radosław Sikorski. Warsaw: AMF Plus Group. pp. 129–130. ISBN 9788360532096.

- ↑ "Radek Sikorski English CV" (PDF).

- ↑ "World: Europe – Ted Turner says sorry". BBC News. 21 February 1999. Retrieved 2014-12-10.

- ↑ Rzeczpospolita, Spór o wizy i paszporty, 19 November 2003

- ↑ New Atlantic Initiative

- ↑ "Ronald Reagan". AEI. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ "Poland to Host Meeting of World Dissidents to Mark 25 Years of Solidarity". AEI. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ "Belarus: Conference In Washington Urges "Regime Change" In Minsk". AEI. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ "Ukraine's Choice". AEI. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ "Election results".

- ↑ Polska, Grupa Wirtualna (2006-01-03). "Min. Sikorski odtajnił akta Układu Warszawskiego". wiadomosci.wp.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ "MON znalazł powód formalny. Wolińska bez emerytury". gazetapl (in Polish). Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ Warzecha, Łukasz (2007). Commie-free Zone: Extended Interview with Radosław Sikorski. Warsaw: AMF Plus Group. p. 165. ISBN 9788360532096.

- ↑ "Wyborcza.pl". wyborcza.pl. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ ""Wiadomości" TVP ujawniły teczkę Radosława Sikorskiego". www.pb.pl. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ "Sikorski: Macierewicz the reason for my departure".

- ↑ "Election results".

- ↑ "Tusk government sworn in".

- ↑ "New Members of the National Board".

- ↑ "Remarks, Speeches & Statements by the Minister of Foreign Affairs Radosław Sikorski". www.msz.gov.pl. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ "Polish Fm a Local Favorite in Nato Race". Poland Warsaw. 2008-12-09.

- ↑ "Wyborcza.pl". wyborcza.pl. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ "Foreign Minister Radosław Sikorski at Weimar Triangle and Russia meeting in Paris". www.mfa.gov.pl. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ ""Bene merito" honorary distinction". www.msz.gov.pl. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ "Lech Walesa Solidarity Prize". www.msz.gov.pl. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ "MSZ sprzedaje ambasady, konsulaty i instytuty". PolskieRadio.pl. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ "Nowa ambasada RP w Brukseli". Onet Wiadomości (in Polish). 2011-05-23. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ "MSZ kupił w Waszyngtonie elegancką rezydencję". Bankier.pl. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ "Nowa siedziba polskiego konsulatu w Londynie". hull.pl | Polacy w Hull (in Polish). 2014-03-29. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ Sikorski, Radosław (27 August 2012). "Minister Radosław Sikorski's address at the Conference of the Heads of Missions of Estonia.".

- ↑ "Polish-led European Endowment for Democracy HQ launched". Polskie Radio dla Zagranicy. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ Recknagel, Charles (2008-09-11). "Lavrov's Poland Visit Sends Mixed Signals On Russia's Crises With West". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ "Lavrov: Belarus Base No Threat To Europe". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. 2013-05-10. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ "Wizyta Ministra Radosława Sikorskiego w Moskwie". www.msz.gov.pl. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ "W maju Sikorski w Moskwie". WPROST.pl. 2009-04-08. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ "Russian Foreign Minister Attends Polish Diplomatic Meeting". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. 2010-09-02. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ "US and Poland seal missile deal". BBC News. 20 August 2008.

- ↑ Kulish, Nicholas (21 August 2008). "Eyeing Georgia, Poland Expresses Worry". New York Times. Retrieved 21 August 2008.

- ↑ Harding, Luke; Traynor, Ian (2009-09-17). "Obama abandons missile defence shield in Europe". the Guardian. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ "Hillary Clinton w Polsce. Aneks podpisany". PolskieRadio.pl. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ "TNS OBOP: Sikorski ahead of Tusk".

- ↑ Sikorski, Radek (28 November 2011). "Poland and the future of the European Union".

- ↑ "Sikorski: German inaction scarier than Germans in action". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ Sikorski, Radoslaw (2011-11-28). "I fear Germany's power less than her inactivity". Financial Times. ISSN 0307-1766. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ "Ukraine crisis: deal signed in effort to end Kiev standoff". The Guardian. 21 February 2014

- ↑ Sikorski, Radosław (17 September 2011). "Eastern Europe and the Role of Ukraine".

- ↑ Sikorski, Radosław (16 April 2012). "Privatisation and private enterprise in Belarus - Scope of international assistance".

- ↑ "Playing East against West: The success of the Eastern Partnership depends on Ukraine". The Economist. 23 November 2013.

- ↑ "100,000 Local Border Traffic permits in Kaliningrad - MFA bolsters ties and supports Polish economy". www.msz.gov.pl. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ "Sikorski i Ławrow podpisali umowę o małym ruchu granicznym". wnp.pl. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ "Polish FM Sikorski to start diplomatic mission in Ukraine at EU request", by Voice of Russia

- ↑ "Foreign minister flies to Ukraine amid Russian troop build up fears". Polskie Radio dla Zagranicy.

- ↑ "Kiev calls for decisive EU action". Polskie Radio dla Zagranicy.

- ↑ Weymouth, Lally (2014-04-17). "Talking with Poland's foreign minister about the Ukraine crisis and Russia's next moves". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ "Polish FM Sikorski to start diplomatic mission in Ukraine at EU request". sputniknews.com. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ "Ukraine president, opposition sign EU-brokered agreement on ending crisis". RT International. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ "Foreign minister flies to Ukraine amid Russian troop build up fears". Polskie Radio dla Zagranicy. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ "Kiev calls for decisive EU action". Polskie Radio dla Zagranicy. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- 1 2 "Sikorski: If Poland is hawkish on Ukraine, is Russia a dove?". EurActiv.com. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ Donahue, Patrick. "Poland's Tusk Proposes Energy Union to Break Russian Hold on Gas". Bloomberg.com. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ Lloyd, By John. "Europeans 'not grasping' the importance of Ukraine". Reuters Blogs. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ "W Sejmie ruszyły prace budowlane. Będzie nowy gmach". PolskieRadio.pl. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ "Zmiany w rządzie. Do dymisji podali się m.in. Arłukowicz i Rostowski. Sikorski też rezygnuje [VIDEO]". Dziennikzachodni.pl. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ "Former Polish foreign minister Sikorski to work at Harvard". Polskie Radio dla Zagranicy. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ "BZPOW". http://www.bzpow.bydg.pl/. Retrieved 2016-09-14. External link in

|website=(help) - ↑ Polska, Grupa Wirtualna (2015-02-19). "Koniec procesu Sikorski kontra "Fakt"". wiadomosci.wp.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ "Radosław Sikorski nie zapłacił za zdjęcie Natalii Siwiec. Kolejne kontrowersje wokół Twittera szefa MSZ". naTemat.pl. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ "Kontrowersje wokół mebli Sikorskiego. Opozycja: To rozrzutność". fakty.interia.pl. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ "Sikorsky: Foreign subversion of Ukraine leads to tragedy". www.kyivpost.com. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- 1 2 Oltermann, Philip; Traynor, Ian; Watt, Nicholas (2014-06-23). "Polish MPs ridicule Cameron's 'stupid propaganda' aimed at Eurosceptics". the Guardian. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- 1 2 "Poland leak: PM Tusk faces questions in parliament - BBC News". BBC News. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ "Poland bugging: The table talk that shook Warsaw - BBC News". BBC News. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ "Wyborcza.pl". wyborcza.pl. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ Warsaw, Reuters in (2014-06-22). "Polish foreign minister says country's alliance with US worthless". the Guardian. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- 1 2 "Radosław Sikorski on Twitter". Twitter. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ "Honorary doctorate for Radoslaw Sikorsky" (PDF). 25 March 2015.

- ↑ "Sikorski, Rubik and Lis winners at the Wiktor 2006 awards".

- ↑ "2011 Freedom Awards". Atlantic Council. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ "Minister of Foreign Affairs Radosław Sikorski".

- ↑ "Radosław Sikorski 16 XI 2007 - 22 IX 2014". www.msz.gov.pl. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ "Minister of Foreign Affairs of Poland, Radosław Sikorski, visits Lithuania".

- ↑ "Appointments to the National Order of Merit" (PDF).

- ↑ "President of the Union of Poles in Lithuania Michal Mackiewicz Visits Poland".

- ↑ "Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Poland, Radosław Sikorski – Biography".

- ↑ "Radek Sikorski - Leigh Bureau Ltd.". www.leighbureaultd.com. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ "High Hungarian distinction awarded to chief of Poland's diplomacy". www.msz.gov.pl. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ "Polish foreign minister on visit to Moldova". www.msz.gov.pl. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ "Zabytkowy dwór Sikorskich pod Bydgoszczą: 'To była totalna ruina...'". bryla.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ↑ "Mr. Perfect from Warsaw: The Rise of Poland's Foreign Minister". Spiegel.de. 30 May 2014. Retrieved 30 May 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Radosław Sikorski. |

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Interview with Radosław Sikorski in PLUS Journal

- Interview with Radosław Sikorski in Fletcher Forum of World Affairs

- Fareed Zakaria interviews Polish Foreign Minister Radosław Sikorski to discuss NATO and the Russia-Georgia conflict on CNN.

- NATO's Past, Present and Future Speech before the Chicago Council on Global Affairs

- The Future of EU-Russia Relations, The New York Times

- Why the World needs a New Start, The Guardian

- Hard Talk Interview with Radosław Sikorski, YouTube

- Radosław Sikorski on Morning Joe MSNBC, YouTube

- Davos Annual Meeting 2010 – Rebuilding Peace and Stability in Afghanistan, YouTube

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Jerzy Szmajdziński |

Minister of National Defence 2005–2007 |

Succeeded by Aleksander Szczygło |

| Preceded by Anna Fotyga |

Minister of Foreign Affairs 2007–2014 |

Succeeded by Grzegorz Schetyna |

| Preceded by Ewa Kopacz |

Marshal of the Sejm 2014–2015 |

Succeeded by Małgorzata Kidawa-Błońska |

| Diplomatic posts | ||

| Preceded by János Martonyi |

President of the Council of the European Union 2011 |

Succeeded by Villy Søvndal |