Nzinga of Ndongo and Matamba

| Queen Ana Nzinga | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Queen of Ndongo | |||||

| Reign | 1624 - 1663 | ||||

| Predecessor | Ngola Kiluanji Kia Samba | ||||

| Successor | Barbara of Matamba | ||||

| Queen of Matamba | |||||

| Reign | 1631 - 1663 | ||||

| Predecessor | Mwongo Matamba | ||||

| Successor | Barbara of Matamba | ||||

| Born |

1583 Angola | ||||

| Died | December 17, 1663 | ||||

| |||||

| House | The Kingdom of the Ndongo | ||||

| Father | King Ngola Kiluanji Kia Samba | ||||

| Mother | Kangela | ||||

Queen Anna Nzinga (c. 1583 – December 17, 1663), also known as Njinga Mbande or Ana de Sousa Nzinga Mbande,[1] was a 17th-century queen (muchino a muhatu) of the Ndongo and Matamba Kingdoms of the Mbundu people in Angola. She came to power as an ambassador after demonstrating a proclivity to tactfully diffuse foreign crisis, as she regained control of the Portuguese fortress of Ambaca. Being the sister of the king, Ngola (King) Mbande, she naturally had an influence on political decisions, when the king assigned her to represent himself in peace negotiations with bordering countries. Nzinga assumed control as regent of his young son, Kaza. Today, she is remembered in Angola for her political and diplomatic acumen, as well as her brilliant military tactics. A major street in Luanda is named after her, and a statue of her was placed in Kinaxixi on a square in 2002, dedicated by President Santos to celebrate the 27th anniversary of independence.

Early life

Nzinga was born to ngola Kia Samba and Guenguela Cakombe around 1583.[2] Queen Anna Nzinga was born in the Portuguese settlement of Angola. She was related to Nzinga Mhemba, who was baptized as Alfonso in 1491 by the Portuguese.[3] Nzinga's father, a dictator, was ruler of the Ndongo and Matamba kingdoms which governed the Mbundu people.[4] Nzinga also had two sisters: Mubkumbu Mbande, or Lady Barbara and Kifunji, or Lady Grace; and Kifunji Mbande, also known as Dona Barbara. When Kia Samba was dethroned some time in the 1610s, his illegitimate son, Mbandi, took power and Nzinga was forced to leave the kingdom since she was his challenger to the throne.[4]

According to tradition, she was named Njinga because her umbilical cord was wrapped around her neck (the Kimbundu verb kujinga means to twist or turn). It was said to be an indication that the person who had this characteristic would be proud and haughty, and a wise woman told her mother that Nzinga would become queen one day. According to her recollections later in life, she was greatly favoured by her father, who allowed her to witness as he governed his kingdom, and who carried her with him to war. She also had a brother, Mbandi, and two sisters, Kifunji and Mukambu. She lived during a period when the Atlantic slave trade and the consolidation of power by the Portuguese in the region were growing rapidly.

In the 16th century, the Portuguese position in the slave trade was threatened by England and France. As a result, the Portuguese shifted their slave-trading activities to the Congo and South West Africa. Mistaking the title of the ruler, ngola, for the name of the country, the Portuguese called the land of the Mbundu people "Angola"—the name by which it is still known today.[1]

Nzinga first appears in historical records as the envoy of her brother, the ngiolssa Ngola Mbandi, at a peace conference with the Portuguese governor João Correia de Sousa in Luanda in 1622.[5] With the death of Ngola Mbandi in 1624 and her election as queen by a faction of the eligible electors from Ngola’s court, Mjinga’s rivals refused to regard her as the legitimate ruler of Ndongo, and they joined with the Portuguese in an attempt to remove her from the throne.

Portuguese Influences on African Countries

Bartering System

Portuguese arrived at the African shore to forcibly capture African people. However, they were not able to reach the shore because the currents were too strong for the type of ships that the Portuguese built and the African boats were more adapted to the shallow waters. Therefore, they were able to defends themselves and many of the African people used poison darts and arrows against any invaders. The Portuguese could not forcefully capture the Africans, so they decided to integrate their culture into their society accordingly so that they can establish trade agreements.

Language

Religion was a barrier at first, both people incapable to communicate with each other, or unable to correspond what each of the people wanted. However, as time passed on, both the Portuguese and Africans used the common language as an advantage for trading. Starting in 1648, Njinga had a literate Kongo-born priest, Don Calisto Zelotes dos Reis Magros, who served as her confessor and secretary. In 1648, Njinga captured him in a war she made against the Kongo region of Wandu. When the Capuchin missionary Gaeta arrived in her court in 1656, Zelotes dos Reis Magros was turned over to the priest to serve as his translator. Zeltoes informed Gaeta that he had been “a slave of the queen for many years.”

Religion

Religion was a way of life, the Portuguese used that notion to control the African people. The Portuguese had to be smart and manipulative, and use tactics that indirectly helped them invade and control most of the African countries. Their tactic was religion; when Christianity was introduced in Africa, their identity and culture was minimized by an outside interference, making the rules that the Portuguese set to make the Africans do what they are told. Queen Nzinga used religion as a barging tool to trade with the Portuguese. When Queen Nzinga converted to Christianity in 1622, she used that as a common ground with the Portuguese to have a common understanding of morals and economic ethics.

Culture

The court system was only a European practice in that time period. Queen Nzinga adapted that practice and was employed in to her society. Creoles were a group of people of a mix breed; for example, Portuguese-African, however not just applying to any or one type of mixed race.

Succession to Power

Portuguese aggression

The Portuguese had set up a slave market on Luanda by 1557, and after this time, the royal family of Ndongo "fought tooth and nail to defend their territory."[6]

Later the Portuguese established themselves near Mbundu land by building a fort and settlement at Luanda in 1617.[7] By 1618, the Portuguese, with the help of their allies, the Imbangala, attacked the Ndongo capital and executed the nobles of the Ndongo dynasty.[8] The Portuguese expected conquered African kingdoms to pay them a tribute in slaves.[8] The slavery tribute was set up by a Portuguese official, Bento Cardoso, in 1608, which "demanded the delivery of slaves to the Portuguese through a Ndongo notable."[9]

Nzinga's Embassy

Mbandi called Nzinga back to the kingdom sometime in 1617 in order to meet with the Portuguese with the goal of securing the independence of Ndongo.[4]

Nzinga was sent to offer a treaty of peace, reaching out to the Portuguese governor of Luanda.[10] The meeting took place in 1622, and Nzinga surprised the delegates, "who were stunned by her self-assurance."[6] The governor, João Correia de Sousa, never gained the advantage at the meeting and agreed to her terms, which resulted in a treaty on equal terms. One important point of disagreement was the question of whether Ndongo surrendered to Portugal and accepted vassalage status. A famous story says that in her meeting with the Portuguese governor, João Correia de Sousa did not offer a chair to sit on during the negotiations, and, instead, had placed a floor mat for her to sit, which in Mbundu custom was appropriate only for subordinates. Not willing to accept this degradation she ordered one of her servants to get down on the ground and sat on the servant's back during negotiations.[7] The scene was imaginatively reconstructed by the Italian priest Cavazzi and printed as an engraving in his book of 1687.

Nzinga converted to Catholicism in 1622, where she was baptized in Luanda.[11] Nzinga may have converted in order to strengthen the peace treaty with the Portuguese, and adopted the name Dona Anna de Sousa in honour of the governor's wife when she was baptised, who was also her godmother. She sometimes used this name in her correspondence (or just Anna). Her first conversion was "done primarily for political reasons and to ingratiate herself to the Portuguese."[4] The Portuguese never honoured the treaty.[12] And despite the alliance with the Portuguese, they continued to raid her kingdom, taking "slaves and precious items" in the process.[10]

Neither withdrawing Ambaca, nor returning the subjects, who they held were slaves captured in war, and they were unable to restrain the Imbangala.

Nzinga's brother committed suicide following this diplomatic impasse, convinced that he would never have been able to recover what he had lost in the war. Rumours were also afoot that Nzinga had actually poisoned him, and these rumours were repeated by the Portuguese as grounds for not honouring her right to succeed her brother.

Nzinga assumed control as regent of his young son, Kaza, who was then residing with the Imbangala. Nzinga sent to have the boy in her charge. The son returned, whom she is alleged to have killed for his impudence. She then assumed the powers of ruling in Ndongo. In her correspondence in 1624 she fancifully styled herself "Lady of Andongo" (senhora de Andongo), but in a letter of 1626 she now called herself "Queen of Andongo" (rainha de Andongo), a title which she bore from then on.

Nzinga had a rival, Hari a Ndongo, who was opposed to a woman ruling.[13] Hari, who was later christened Felipe I, swore vassalage to the Portuguese.[13] With the help of members in the Kasanje Kingdom and Ndongo nobles opposed to Nzinga, she was removed from Luanda, and she fled to Milemba aCangola.[14]

Nzinga was defeated in 1625 and withdrew her forces to the east.[15] The Portuguese set up Nzinga's sister, Kifunji, as a puppet ruler who acted as a loyal spy to Nzinga for many years.[3] Nzinga was able to regroup and strengthen her base of power within the territory of Matamba in 1629.[16] During this time, Nzinga accepted refugees of the slave trade.[16]

During the 1630s, Nzinga was able to seize power in Matamba when the female chief or muhongo Matamba, died.[17]

Dutch Alliance

In 1641, the Dutch, working in alliance with the Kingdom of Kongo, seized Luanda. Nzinga soon sent them an embassy and concluded an alliance with them against the Portuguese who continued to occupy the inland parts of their colony of males with their main headquarters at the town of Masangano. Hoping to recover lost lands with Dutch help, she moved her capital to Kavanga in the northern part of Ndongo's former domains. In 1644 she defeated the Portuguese army at Ngoleme, but was unable to follow up. Then, in 1646, she was defeated by the Portuguese at Kavanga and, in the process, her other sister was captured, along with her archives, which revealed her alliance with Kongo. These archives also showed that her captive sister had been in secret correspondence with Nzinga and had revealed coveted Portuguese plans to her. As a result of the woman's spying, the Portuguese reputedly drowned the sister in the Kwanza River.

However, another account states that the sister managed to escape, and ran away to modern-day Namibia.

The Dutch in Luanda now sent Nzinga reinforcements, and with their help, Nzinga routed a Portuguese army in 1647 at the Battle of Kombi. Nzinga then laid siege to the Portuguese presidios of Ambaca, Muxima and their capital, Masangano. Lacking artillery, the attacks were unsuccessful in dislodging the Portuguese.

As the Portuguese recaptured Luanda with a Brazilian-based assault led by Salvador Correia de Sá the following year in August 15, 1648, Nzinga requested a cease-fire, and was forced to retreat to Matamba where she continued to skirmish against the Portuguese well into her sixties, personally leading troops into battle.

Final Years

In 1657, weary from the long struggle against the Portuguese, Nzinga requested a new peace treaty. The church "re-accepted" Nzinga in 1656.[11] She converted again to Catholicism in 1657.[16] Along with the Capuchins, she promoted churches in her kingdom.[11] After the wars with Portugal ended, she attempted to rebuild her nation, which had been seriously damaged by years of conflict and over-farming. She was anxious that Njinga Mona's Imbangala not succeed her as ruler of the combined kingdom of Ndongo and Matamba, and inserted language in the treaty that bound Portugal to assist her family to retain power. Lacking a son to succeed her, she tried to vest power in the Ngola Kanini family and arranged for her sister to marry João Guterres Ngola Kanini and to succeed her. This marriage, however, was not allowed, as priests maintained that João had a wife in Ambaca. She returned to the Christian church to distance herself ideologically from the Imbangala, and took a Kongo priest Calisto Zelotes dos Reis Magros as her personal confessor. She permitted Capuchin missionaries, first Antonio da Gaeta and the Giovanni Antonio Cavazzi da Montecuccolo to preach to her people. Both wrote lengthy accounts of her life, kingdom, and strong will.

She devoted her efforts to resettling former slaves and allowing women to bear children. Despite numerous efforts to dethrone her, especially by Kasanje, whose Imbangala band settled to her south, Nzinga would die a peaceful death at the age of eighty on 17 December 1663 in Matamba. Matamba went though a civil war in her absence, but Francisco Guterres Ngola Kanini eventually carried on the royal line in the kingdom. Her death accelerated the Portuguese occupation of the interior of South West Africa, fueled by the massive expansion of the Portuguese slave trade. Portugal would not have control of the interior until the 20th century. By 1671, Ndongo became part of Portuguese Angola.[18]

Legacy

Today, she is remembered in Angola for her political and diplomatic acumen, as well as her brilliant military tactics. Accounts of her life are often romanticized, and she is considered a symbol of the fight against oppression.[19]

A major street in Luanda is named after her, and a statue of her was placed in Kinaxixi on an impressive square in 2002, dedicated by President Santos to celebrate the 27th anniversary of independence. Angolan women are often married near the statue, especially on Thursdays and Fridays.

The National Reserve Bank of Angola (BNA) issued a series of coins in tribute to Nzinga "in recognition of her role to defend self-determination and cultural identity of her people."[20]

An Angolan film, Nzinga, Queen of Angola (Portuguese: Njinga, Rainha de Angola), was released in 2013.[21]

Name Variations

Nzinga has many variations on her name and, in some cases, is even known by completely different names, because of the multiple aliases she used in correspondence with the Portuguese. These names include (but are not limited to): Queen Nzinga, Nzinga I, Queen Nzinga Mdongo, Nzinga Mbandi, Nzinga Mbande, Jinga, Singa, Zhinga, Ginga, Njinga, Njingha, Ana Nzinga, Ngola Nzinga, Nzinga of Matamba, Queen Nzinga of Ndongo, Zinga, Zingua, Ann Nzinga, Nxingha, Mbande Ana Nzinga, Ann Nzinga, Anna de Sousa, and Dona Ana de Sousa.

In current Kimbundu language, her name should be spelled Njinga, with the second letter being a soft "j" as the letter is pronounced in French and Portuguese. She wrote her name in several letters as "Ginga". She was perceived to be biologically female but dressed as male, also called "King" on many occasions. The statue of Njinga now standing in the square of Kinaxixi in Luanda calls her "Mwene Njinga Mbande".

In Literature and Legend

According to the Marquis de Sade’s Philosophy in the Boudoir, Nzinga was a woman who "immolated her lovers." De Sade's reference for this comes from History of Zangua, Queen of Angola. It claims that after becoming queen, she obtained a large, all male harem at her disposal. These men wore women's clothing and were known as chibados.[22]

Her men fought to the death in order to spend the night with her and, after a single night of lovemaking, were put to death. It is also said that Nzinga made her male servants dress as women. In 1633, Nzinga's oldest brother died of cancer, which some attribute to her.

Sources

Nzinga is one of Africa's best documented early-modern rulers. About a dozen of her own letters are known (all but one published in Brásio, Monumenta volumes 6-11 and 15 passim). In addition, her early years are well described in the correspondence of Portuguese governor Fernão de Sousa, who was in the colony from 1624 to 1631 (published by Heintze). Her later activities are documented by the Portuguese chronicler António de Oliveira de Cadornega, and by two Italian Capuchin priests, Giovanni Cavazzi da Montecuccolo and Antonio Gaeta da Napoli, who resided in her court from 1658 until her death (Cavazzi presided at her funeral). Cavazzi included a number of watercolours in his manuscript which include Njinga as a central figure, as well as himself.

- Brásio,António. Monumenta Missionaria Africana (1st series, 15 volumes, Lisbon: Agencia Geral do Ultramar, 1952–88)

- Cadornega, António de Oliveira de. História geral das guerras angolanas (1680-81). mod. ed. José Matias Delgado and Manuel Alves da Cunha. 3 vols. (Lisbon, 1940–42) (reprinted 1972).

- Cavazzi, Giovanni Antonio da Montecuccolo. Istorica descrizione de tre regni Congo, Matamba ed Angola. (Bologna, 1687). French translation, Jean Baptiste Labat, Relation historique de l'Éthiopie. 5 vols. (Paris, 1732) [a free translation with additional materials added]. Modern Portuguese translation, Graziano Maria Saccardo da Leguzzano, ed. Francisco Leite de Faria, Descrição histórica dos tres reinos Congo, Matamba e Angola. 2 vols. (Lisbon, 1965).

- Gaeta da Napoli, Antonio. La Meravigliosa Conversione alla santa Fede di Christo delle Regina Singa...(Naples, 1668).

- Heintze, Beatrix. Fontes para a história de Angola no século XVII. (2 vols, Wiesbaden, 1985–88) Contains the correspondence of Fernão de Souza.

- Narratives from the Early Modern Ibero-Atlantic World, 1550-1812. Edited by Kathryn, Joy McKnight & Leo J. Garofalo, 2009 - 416 pp. 38–51

- Lewis, Jone Johnson. "Anna Nzinga: Queen Nzinga, seated on a kneeling man, receives Portuguese invaders." About Education (2016): 1.

See also

- List of Ngolas of Ndongo

- List of Rulers of Matamba

- List of women who led a revolt or rebellion

- Matamba

- Ndongo

- Nzinga a Nkuwu

- Pungo Andongo

References

Citations

- 1 2 Williams 2010, p. 82.

- ↑ Williams 2010, p. 83.

- 1 2 Jackson, Guida M. (1990). Women Who Ruled: A Biographical Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 130. ISBN 0874365600.

- 1 2 3 4 Page 2001, p. 198.

- ↑ "Black History Heroes: Queen Ana de Sousa Nzinga Mbande of Ndongo (Angola)". Retrieved 7 December 2014.

- 1 2 Serbin and Rasoanaivo-Randriamamonjy 2015, p. 20.

- 1 2 Snethen, Jessica. "Queen Nzinga (1583-1663)". Black Past.org. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- 1 2 Njoku 1997, p. 38.

- ↑ Williams 2010, p. 82-83.

- 1 2 Njoka 1997, p. 39.

- 1 2 3 The Church in the Age of Absolutism and Enlightenment. Translated by Gunther J. Holst. New York: The Crossroad Publishing Company. 1981. p. 273. ISBN 0824500105.

- ↑ Thornton 2011, p. 182-183.

- 1 2 Thornton 2011, p. 183.

- ↑ Vansina 1963, p. 360.

- ↑ Reid, Richard J. (2012). Warfare in African History. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 71. ISBN 9780521123976.

- 1 2 3 Serbin and Rasoanaivo-Randriamamonjy 2015, p. 21.

- ↑ Page 2001, p. 164.

- ↑ Page 2001, p. 190.

- ↑ Thornton 1991, p. 25.

- ↑ "Angola to Launch New Kwanza Coins in 2015". Mena Report. 26 December 2014. Retrieved 26 June 2016 – via HighBeam Research. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "Njinga, Queen of Angola (Njinga, Rainha de Angola) UK Premiere". Royal African Society's Annual Film Festival. 6 November 2014. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- ↑ Bleys, Rudi C. (1995). The Geography of Perversion: Male-to-Male Sexual Behavior Outside the West and the Ethnographic Imagination, 1750-1918. New York University Press. ISBN 9780814712658.

Sources

- Njoku, Onwuka N. (1997). Mbundu. New York: The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. ISBN 0823920046.

- Page, Willie F. (2001). Encyclopedia of African History and Culture: From Conquest to Colonization (1500-1850). 3. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 0816044724.

- Serbin, Sylvia; Rasoanaivo-Randriamamonjy, Ravaomalala (2015). African Women, Pan-Africanism and African Renaissance. Paris: UNESCO. ISBN 9789231001307.

- Thornton, John K. (1991). "Legitimacy and Political Power: Queen Njinga, 1624-1663". The Journal of African History. 32 (1): 25–40. doi:10.1017/s0021853700025329. JSTOR 182577. (subscription required (help)).

- Thornton, John K. (2011). "Firearms, Diplomacy, and Conquest in Angola: Cooperation and Alliance in West Central Africa, 1491-1671". In Lee, Wayne E. Empires and Indigenes: Intercultural Alliance, Imperial Expansion and Warfare in the Early Modern World. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 9780814753095.

- Vansina, Jan (1963). "The Foundation of the Kingdom of Kasanje". The Journal of African History. 4 (3): 355–374. doi:10.1017/s0021853700004291. JSTOR 180028. (subscription required (help)).

- Williams, Hettie V. (2010). "Queen Nzinga (Njinga Mbande)". In Alexander, Leslie M.; Rucker, Walter C. Encyclopedia of African American History. 1. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781851097746.

Further reading

- Black Women in Antiquity, Ivan Van Sertima (ed.). Transaction Books, 1990

- Patricia McKissack, Nzingha: Warrior Queen of Matamba, Angola, Africa, 1595 ; The Royal Diaries Collection (2000)

- David Birmingham, Trade and Conquest in Angola (Oxford, 1966).

- Heywood, Linda and John K. Thornton, Central Africans, Atlantic Creoles, and the Making of the Americas, 1580-1660 (Cambridge, 2007). This contains the most detailed account of her reign and times, based on a careful examination of all the relevant documentation.

- Saccardo, Grazziano, Congo e Angola con la storia dell'antica missione dei cappuccini 3 Volumes, (Venice, 1982–83)

- Williams, Chancellor, Destruction of Black Civilization (WCP)

- van Sertima, Ivan, Black Women in Antiquity

- Nzinga, the Warrior Queen ( a play written by Elizabeth Orchardson Mazrui and published by The Jomo Kenyatta Foundation, Nairobi, Kenya, 2006). The play is based on Nzinga and discusses issues of colonisation, traditional African ruleship, women leadership versus male leadership, political succession, struggles between various Portuguese socio-political, and economic interest groups, struggles between the vested interests of the Jesuits and the Capuchins, etc.

- West Central Africa: Kongo, Ndongo (African Kingdoms of the Past), Kenny Mann. Dillon Press, 1996.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Njinga Mbandi. |

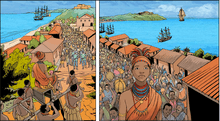

- Bio-Comic strip at Wikimedia Commons, Pat Masioni et al.

- Ana Nzinga: Queen of Ndongo at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Women Who Lead

]