Queen Emma of Hawaii

| Emma | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Queen consort of the Hawaiian Islands | |||||

| |||||

| Tenure | June 19, 1856 – November 30, 1863 | ||||

| Born |

January 2, 1836 Honolulu, Oahu | ||||

| Died |

April 25, 1885 (aged 49) Honolulu, Oahu | ||||

| Burial |

May 17, 1885[1][2] Mauna ʻAla Royal Mausoleum | ||||

| Spouse | Kamehameha IV | ||||

| Issue | Albert Edward Kauikeaouli Kaleiopapa a Kamehameha | ||||

| |||||

| House | Kamehameha | ||||

| Father |

High Chief George Naʻea Thomas Rooke (hānai) | ||||

| Mother |

High Chiefess Fanny Kekelaokalani Young High Chiefess Grace Kamaʻikuʻi Young Rooke (hānai) | ||||

| Religion | Church of Hawaii | ||||

| Signature |

| ||||

Emma Kalanikaumakaʻamano Kaleleonālani Naʻea Rooke of Hawaiʻi (January 2, 1836 – April 25, 1885) was queen consort of King Kamehameha IV from 1856 to his death in 1863. She ran for ruling monarch against King Kalākaua but was defeated.

Life

Early life

Emma was born on January 2, 1836 in Honolulu and was often called Emalani ("royal Emma"). Her father was High Chief George Naʻea and her mother was High Chiefess Fanny Kekelaokalani Young.[3] She was adopted under the Hawaiian tradition of hānai by her childless maternal aunt, chiefess Grace Kamaʻikuʻi Young Rooke, and her husband, Dr. Thomas C. B. Rooke.

Emma's father Naʻea was the son of High Chief Kamaunu and High Chiefess Kukaeleiki.[4] Kukaeleiki was daughter of Kalauawa, a Kauaʻi noble, and she was a cousin of Queen Keōpūolani, the most sacred wife of Kamehameha I. Among Naʻea's more notable ancestors were Kalanawaʻa, a high chief of Oʻahu, and High Chiefess Kuaenaokalani, who held the sacred kapu rank of Kekapupoʻohoʻolewaikala (so sacred that she could not be exposed to the sun except at dawn).[5]:4

On her mother's side, Emma was the granddaughter of John Young, Kamehameha I's British-born military advisor known as High Chief Olohana, and Princess Kaʻōanaʻeha Kuamoʻo.[6] Her maternal grandmother, Kaʻōanaʻeha, was generally called the niece of Kamehameha I. Chiefess Kaʻōanaʻeha's father is disputed; some say she was the daughter of Prince Keliʻimaikaʻi, the only full brother of Kamehameha; others state Kaʻōanaʻeha's father was High Chief Kalaipaihala.[7][8] This confusion is due to the fact that High Chiefess Kalikoʻokalani, the mother of Kaʻōanaʻeha, married both to Keliʻimaikaʻi and to Kalaipaihala. Through High Chief Kalaipaihala, she could be descended from Kalaniʻopuʻu, King of Hawaii before Kīwalaʻō and Kamehameha. King Kalākaua and Queen Liliʻuokalani criticized Queen Emma's claim of descent from Kamehameha's brother, supporting the latter theory of descent. Liliʻuokalani claimed that Keliʻimaikaʻi had no children, and that Kiilaweau, Keliʻimaikaʻi's first wife, was a man.[9]:404 This was to strengthen their claim to the throne, since their great-grandfather was Kamehameha I's first cousin. But even through the second theory Queen Emma would still have been descendant of Kamehameha I's first cousin since Kalaniʻopuʻu was the uncle of Kamehameha I.[5]:357–358 It can be noted that one historian of the time, Samuel Kamakau,[10] supported Queen Emma's descent from Keliʻimaikaʻi and the genealogy stated by Liliuokalani have been contested in her own lifetime.[11]

Emma grew up at her foster parents' English mansion, the Rooke House, in Honolulu. Emma was educated at the Royal School, which was established by American missionaries. Other Hawaiian royals attending the school included Emma's half-sister Mary Paʻaʻāina. Like her classmates Bernice Pauahi Bishop, David Kalākaua and Lydia Liliʻuokalani, Emma was cross-cultural — both Hawaiian and Euro-American in her habits. But she often found herself at odds with her peers. Unlike many of them, she was neither romantic nor prone to hyperbole. When the school closed, Dr. Rooke hired an English governess, Sarah Rhodes von Pfister, to tutor the young Emma. He also encouraged reading from his extensive library. As a writer, he influenced Emma's interest in reading and books. By the time she was 20, she was an accomplished young woman. She was 5' 2" and slender, with large black eyes. Her musical talents as a vocalist, pianist and dancer were well known. She was also a skilled equestrian.

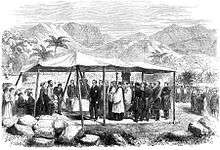

Married life and reign

Emma became engaged to the king of Hawaii, Alexander Liholiho. At the engagement party, a Hawaiian charged that Emma's Caucasian blood made her unfit to be the Hawaiian queen and her lineage was not suitable enough to be Alexander Liholiho's bride; she broke into tears and the king was infuriated. On June 19, 1856, she married Alexander Liholiho, who a year earlier had assumed the throne as Kamehameha IV. He was also fluent in both Hawaiian and English. Each nation and even the Chinese hosted balls and celebrations in honor of the newlyweds. Two years later on May 20, 1858 Emma gave birth to a son, Prince Albert Edward Kamehameha.

The queen tended palace affairs, including the expansion of the palace library. She was known for her humanitarian efforts. Inspired by her adoptive father's work, she encouraged her husband to establish a public hospital to help the Native Hawaiians who were in decline due to foreign-borne diseases like smallpox. In 1859, Emma established Queen's Hospital and visited patients there almost daily whenever she was in residence in Honolulu. It is now called the Queen's Medical Center.

Prince Albert, who was always called "Baby" by Emma, had been celebrated for days at his birth and every public appearance. Mary Allen, wife of the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court Elisha Hunt Allen, had a son Frederick about the same age, and they became playmates. In 1862, Queen Victoria agreed to become godmother by proxy, and sent an elaborate silver christening cup. Before the cup could arrive, the prince fell ill in August and condition worsened. The Prince died on August 27, 1862. Her husband died a year later, and Emma would not have any more children.[12]

Names

After her son's death and before her husband's death, she was referred to as "Kaleleokalani", or "flight of the heavenly one". After her husband also died, it was changed into the plural form as "Kaleleonālani", or the "flight of the heavenly ones". She was baptized into the Anglican faith on October 21, 1862 as "Emma Alexandrina Francis Agnes Lowder Byde Rook Young Kaleleokalani.[5]:152

Queen Emma was also nicknamed "Wahine Holo Lio" in deference to her renowned horsemanship.

Religious legacy

In 1860, Queen Emma and King Kamehameha IV petitioned the Church of England to help establish the Church of Hawaii. Upon the arrival of Anglican bishop Thomas Nettleship Staley and two priests, they both were baptized on October 21, 1862 and confirmed in November 1862. With her husband, she championed the Anglican (Episcopal) church in Hawaii and founded St. Andrew’s Cathedral, raising funds for the building. In 1867 she founded Saint Andrew's Priory School for Girls.[13] She also laid the groundwork for an Episcopal secondary school for boys originally named for Saint Alban, and later ʻIolani School in honor of her husband. Emma and King Kamehameha IV are honored with a feast day of November 28 on the liturgical calendar of the U.S. Episcopal Church.[14][15]

Royal election of 1874

After the death of King Lunalilo, Emma decided to run in the constitutionally-mandated royal election against future King Kalākaua. She claimed that Lunalilo had wanted her to succeed him, but died before a formal proclamation could be made.

The day after Lunalilo died, Kalākaua declared himself candidate for the throne. The next day Queen Emma did the same. The first real animosity between the Kamehamehas and Kalākaua begun to appear, as he published a proclamation:

"To the Hawaiian Nation."

“Salutations to You—Whereas His Majesty Lunalilo departed this life at the hour of nine o'clock last night; and by his death the Throne of Hawaii is left vacant, and the nation is without a head or a guide. In this juncture it is proper that we should seek for a Sovereign and Leader, and doing so, follow the course prescribed by Article 22nd of the Constitution. My earnest desire is for the perpetuity of the Crown and the permanent independence of the government and people of Hawaii, on the basis of the equity, liberty, prosperity, progress and protection of the whole people.It will be remembered that at the time of the election of the late lamented Sovereign, I put forward my own claim to the Throne of our beloved country, on Constitutional grounds — and it is upon those grounds only that I now prefer my claims, and call upon you to listen to my call, and request you to instruct your Representatives to consider, and weigh well, and to regard your choice to elect me, the oldest member of a family high in rank in the country.

Therefore, I, David Kalakaua, cheerfully call upon you, and respectfully ask you to grant me your support."

D. KALAKAUA

Iolani Palace, Feb. 4, 1874.

Queen Emma issued her proclamation the next day:

“To the Hawaiian People:

"Whereas, His late lamented Majesty Lunalilo died on the 3rd of February, 1874, without having publicly proclaimed a Successor to the Throne; and whereas, "His late Majesty did before his final sickness declare his wish and intention that the undersigned should be his Successor on the Throne of the Hawaiian Islands, and enjoined upon me not to decline the same under any circumstances; and whereas. "Many of the Hawaiian people have since the death of His Majesty urged me to place myself in nomination at the ensuing session of the Legislature; "Therefore, in view of the foregoing considerations and my duty to the people and to the memory of the late King, I do hereby announce and declare that I am a Candidate for the Throne of these Hawaiian Islands, and I request my beloved people throughout the group, to assemble peacefully ad orderly in their districts, and to give formal expression to their views on this important subject, and to instruct their Representatives in the coming session of the Legislature. "God Protect Hawaii!"

"Honolulu, Feb. 5, 1874.

EMMA KALELEONALANI. "[5]:283

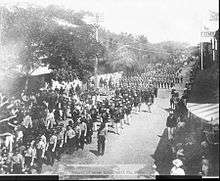

Emma's candidacy was agreeable to many Native Hawaiians, not only because her husband was a member of the Kamehameha Dynasty, but she was also closer in descent to Hawaii's first king, Kamehameha The Great, than her opponent. On foreign policy, she (like her husband) were pro-British while Kalākaua, although being pro-Hawaiian and somewhat pro-British, was more leaning toward the American. She also strongly wished to stop Hawaii's dependence on American industry and to give the Native Hawaiians a more powerful voice in government. While the people supported Emma, the Legislative Assembly, which actually elected the new monarch, favored Kalākaua, who won the election 39 – 6. News of her defeat caused a large-scale riot in which thirteen legislators supporting Kalākaua were injured; one, J. W. Lonoaea, ultimately died of his injuries.[16] The riot was eventually dispersed due to the assistance of both British and American troops stationed on warships in Honolulu Harbor.

After the election, she retired from public life. While she would come to recognize Kalākaua as the rightful king, she would never speak with his wife Queen Kapiʻolani.

As Queen Dowager

After the death of her husband and son, she remained a widow for the rest of her life. Known affectionately as the "Old Queen", King Kalākaua left a seat for her at any royal occasion, even though she rarely attended. Specific conspicuous events that Emma did not attend were:

- Liliʻuokalani's birthday celebration at Aliʻiolani Hale

- Receptions for high foreign officials and guests (including American Admiral Stevens of the USS Pensacola and the new minister of Foreign Affairs)

- The laying of the foundation of Lunalilo Home.

Emma would never attend any event with either Liliʻuokalani or Kapiʻolani. This was because Emma had blamed the death of Albert on Queen Kapiʻolani, who was supposed to be the child's governess.

Despite the great differences in their kingdoms, Queen Emma and Queen Victoria became lifelong friends; both had lost sons and spouses. They exchanged letters, and Emma traveled to London in 1865 to visit and spend a night at Windsor Castle on November 27. Queen Victoria remarked of Emma, "Nothing could be nicer or more dignified than her manner."[17]

On her way back, she had a reception given for her on August 14, 1866 by Andrew Johnson at the White House.[18] Some note this as the first time anyone with the title "Queen" had had an official visit to the U.S. presidential residence.[19]

Emma was known to be strongly against republicanism, she was once quoted as saying:

"We have yet the right to dispose of our country as we wish, and be assured that it will never be to a Republic!"

Impressions

Queen Emma was warmly received by Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom. The two widow queens sympathized with each other and Queen Victoria recorded in her journal on the afternoon of September 9, 1865:

"After luncheon I received Queen Emma, the widowed Queen of the Sandwich Islands or Hawaii. Met her in the Corridor & nothing could be nicer or more dignified than her manner. She is dark, but not more so than an Indian, with fine feathers [features?] & splendid soft eyes. She was dressed in just the same widow's weeds as I wear. I took her into the White Drawing room, where I asked to sit down next to me on the sofa. She was moved when I spoke to her of her great misfortune in losing her only child. She was very discreet & would only remain a few minutes. She presented her lady, Mrs. Hoopile whose husband is her Chaplain, both being Hawaiians...."[5]:199–200

Isabella Bird, on her travels to Hawaii, met Queen Emma and described her as very British and Hawaiian in many ways:

"Miss W. kindly introduced me to Queen Emma, or Kaleleonalani, the widowed queen of Kamehameha IV., whom you will remember as having visited England a few years ago, when she received great attention. She has one-fourth of English blood in her veins, but her complexion is fully as dark as if she were of unmixed Hawaiian descent, and her features, though refined by education and circumstances, are also Hawaiian; but she is a very pretty, as well as a very graceful woman. She was brought up by Dr. Rooke, an English physician here, and though educated at the American school for the children of chiefs, is very English in her leanings and sympathies, an attached member of the English Church, and an ardent supporter of the “Honolulu Mission.” Socially she is very popular, and her exceeding kindness and benevolence, with her strongly national feeling as an Hawaiian, make her much beloved by the natives."[20]

in an interview, Kanahele, author of Queen Emma: Hawaii's remarkable queen said :

"She was different from any of her contemporaries. Emma is Emma is Emma. There’s no one like her. A devout Christian who chose to be baptized in the Anglican church in adulthood, and a typically Victorian woman who wore widow’s weeds, gardened, drank tea, patronized charities and gave dinner parties, she yet remained quintessentially Hawaiian. She wrote exquisite chants of lament in Hawaiian, craved Hawaiian food when she was away from it, loved to fish, hike, ride and camp out (activities she kept up to the end of her life) and, throughout her life, took very seriously her role as a protector of the people’s welfare. In a way, she was a harbinger of things to come in terms of Hawaii’s multi-ethnic, multi-cultural society. You have to be impressed with her eclecticism — spiritually, emotionally and physically. She was kind of our first renaissance queen."[5]

Death and legacy

In 1883, Emma suffered the first of several small strokes and died two years later on April 25, 1885 at the age of 49.

At first she was laid in state at her house; but Alexander Cartwright and a few of his friends moved the casket to Kawaiahaʻo Church, saying her house was not large enough for the funeral. This was evidently not popular with those in charge of the church, since it was Congregational; Queen Emma had been a supporter of the Anglican Mission, and was an Episcopalian. Queen Liliʻuokalani said it "...showed no regard for the sacredness of the place". However, for the funeral service, Bishop Alfred Willis of the English Church officiated in the Congregational church with his ritual. She was given a royal procession and was interred in the Royal Mausoleum of Hawaii known as Mauna ʻAla, next to her husband and son.[9]:108–109

The Queen Emma Foundation was set up to provide continuous lease income for the hospital. Its landholding in the division known as the Queen Emma Land Company include the International Marketplace and Waikiki Town Center buildings.[21][22] Some of the 40 year leases expire in 2010.[23] The area known as Fort Kamehameha in World War II, the site of several coastal artillery batteries, was the site of her former beach-front estate. After annexation it was acquired by the U.S. federal government in 1907.[24]

The Emalani festival, Eo e Emalani i Alakaʻi held in October on the island of Kauaʻi in Koke'e State Park celebrates an 1871 visit.[25]

Honours

-

Dame Grand Cross of the Most Noble Order of Kamehameha I (04/02/1879).[26]

Dame Grand Cross of the Most Noble Order of Kamehameha I (04/02/1879).[26]

Family tree

| Family tree | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

- Hānaiakamalama (Queen Emma Summer Palace)

- The Queen's Medical Center

References

- ↑ Roger G. Rose; Sheila Conant & Eric P. Kjellgren. "Hawaiian standing kahili in the Bishop museum: An ethnological and biological analysis". Journal of the Polynesian Society: 273–304. Retrieved 2011-09-18.

- ↑ David W. Forbes, ed. (2003). Hawaiian national bibliography, 1780-1900. 4. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 144–145. ISBN 0-8248-2636-1.

- ↑ "Queen Emma "Kaleleonalani" Naea". Our Family History and Ancestry. Families of Old Hawaii. Retrieved 2009-12-04.

- ↑ Edith K. McKinzie & Ishmael W. Stagner (1983). Hawaiian Genealogies: Extracted from Hawaiian Language Newspapers. 1. University of Hawaii Press. p. 73. ISBN 0-939154-28-5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 George S. Kanahele (1999). Emma: Hawai'i's Remarkable Queen: a Biography. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2240-8.

- ↑ Emmett Cahill (1999). The Life and Times of John Young: Confidant and Advisor to Kamehameha the Great. Island Heritage Publishing, Aiea Hawaii. p. 147. ISBN 978-0-89610-449-5.

- ↑ Kapiikauinamoku (June 20, 1955). "The Story of Maui Royalty: Princess Kamamalu Was Kamehamehaʻs Daughter". Honolulu Advertiser. Retrieved 2010-01-01.

- ↑ Kapiikauinamoku (October 25, 1955). "The Story of Hawaiian Royalty: Princess Princess Kaoanaeha Is Married to John Young: The Kaleipaihala Controversy: 2". Honolulu Advertiser. Retrieved 2010-03-05.

- 1 2 Queen Liliʻuokalani (July 25, 2007) [1898]. Hawaii's story by Hawaii's queen, Liliuokalani. Lee and Shepard, reprinted by Kessinger Publishing, LLC. ISBN 978-0-548-22265-2.

- ↑ Kamakau, Samuel (1992) [1961]. Ruling Chiefs of Hawaii (Revised ed.). Honolulu: Kamehameha Schools Press. ISBN 0-87336-014-1.

- ↑ Robert William Wilcox (27 May 1898). "Some Geneology. R. W. Wilcox Corrects Statements in Ex-Queen's Book. Ancestry of Liliuokalani. Only Surviving Members of Royal School Destined to Be Rulers of Hawaii". Hawaiian Gazette. Retrieved 14 April 2012.

- ↑ Rhoda E. A. Hackler (1992). "Albert Edward Kauikeaouli Leiopapa a Kamehameha, Prince of Hawai'i". Hawaiian Journal of History. 26. Hawaii Historical Society. pp. 21–44. hdl:10524/349.

- ↑ "St. Andrew's Priory School". official web site. Retrieved 2010-01-29.

- ↑ The proper for the lesser Feasts and Fasts (Church Publishing Company, 2003)

- ↑ The Book of common prayer and administration of the sacraments and other rites and ceremonies of the church. Church Publishing, Incorporated, New York. 1979. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-89869-060-6.

- ↑ Dabagh, Jean; Lyons, Curtis Jere; Hitchcock, Harvey Rexford (1974). Dabagh, Jean, ed. "A King is Elected: One Hundred Years Ago" (PDF). Hawaiian Journal of History. 8: 76–89.

- ↑ Rhoda E. A. Hackler (1988). ""My Dear Friend": Letters of Queen Victoria and Queen Emma". Hawaiian Journal of History. 22. Hawaii Historical Society. pp. 101–130. hdl:10524/202.

- ↑ Esther Singleton (1907). The story of the White House. Volume 2. The McClure company. p. 109.

- ↑ Steven Anzovin, Janet Podell (2001). Famous first facts about American politics. H.W. Wilson. p. 136.

- ↑ Isabella Lucy Bird (1875). The Hawaiian Archipelago: Six Months Among the Palm Groves, Coral Reefs, and Volcanoes of the Sandwich Islands. London: John Murray. p. 262.

- ↑ Janis L. Magin (September 24, 2008). "New plan for International Market Place announced". Pacific Business News (Honolulu).

- ↑ "Queen Emma Kaleleonalani". International Market Place and Waikiki Town Center web site. Queen Emma Land Company. Retrieved 2010-02-01.

- ↑ Allison Schaefers (May 19, 2009). "Queen Emma has tract ideas: No agreement could be reached on the Waikiki land parcel". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Retrieved 2010-03-02.

- ↑ Gregg K. Kakesako (October 27, 1997). "Fort Kamehameha looks nothing like it did in 1920: The post used to guard Pearl Harbor's entrance but is now part of Hickam". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Retrieved 2010-02-01.

- ↑ "Eo e Emalani i Alaka'i — The Emalani Festival". Hui o Laka, Kōkeʻe Museum. Retrieved 2010-02-01.

- ↑ Christopher Buyers. "The Kamehameha Dynasty Genealogy (Page 7)". Royal Ark web site. Retrieved May 21, 2013.

Further reading

- Barbara Bennett Peterson (2003). Emalani: Queen Emma Kaleleonālani. Daughters of Hawaii Publications Committee. ISBN 978-0-938851-14-1.

- Nesta Obermer, Paul Larsen (1960). E Ola o Emmalani (Queen Emma speaks). Queen's Hospital Honolulu.

- Kaeo, Peter; Queen Emma (1976). Korn, Alfons L., ed. News from Molokai, Letters Between Peter Kaeo & Queen Emma, 1873–1876. Honolulu: The University Press of Hawaii. ISBN 978-0-8248-0399-5.

- Emma (1976). He lei no ʻEmalani. Translated by Puakea Nogelmeier. Queen Emma Foundation. ISBN 978-1-58178-009-3. (songbook)

- King David Kalakaua (1888). Hawaiian Legends: Introduction.

- Charles Ahlo (2000). Kamehameha's Children Today. Bishop Museum Honolulu.

- David Kaonohiokala Bray & Douglas Low (1980). The Kahuna Religion of Hawai'i. Borderland Sciences & Research Foundation, Inc. Garberville, CA.

- Mary Pukui & Samuel A. Elbert (1986). Hawaiian Dictionary. University of Hawaii Press Honolulu Hawaii.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Queen Emma of Hawaii. |

- Jeffrey Bingham Mead (March 9, 2011). "Japanese Bow to Queen Emma, Western Women and Hoop Skirts in Hawaii". 1860: Japanese Embassy to America Visits Hawaii. Retrieved July 5, 2015.

- Darlene E. Kelley (April 30, 2001). "Kalakaua — Part 11". Keepers of the Culture. US GenWeb Archives. Retrieved 2010-02-01.

- "Emma, Queen Dowager of Hawaii". Harper's Weekly (A Journal of Civilization). August 9, 1865. Retrieved 2010-02-01.

- "Biography of Founder Queen Emma". The Queen's Medical Center. Retrieved 2009-12-30.

- Jessica from Pukalani. "Woman Hero: Queen Emma". My Hero web site. Retrieved 2010-02-01.

- Will Hoover (July 2, 2006). "Queen Emma". The Honolulu Advertiser. Retrieved 2010-02-01.

- Emma Kaleleonalani at Find a Grave

- Laurie Schoonmaker. "Thoughts of a Queen". Horizons 2001. Kapiolani Community College. Retrieved 2010-02-01.

- James Kiefer (October 1, 2009). "King Kamehameha and Queen Emma of Hawaii (28 NOV 1864)". The Lectionary: A collection of Lectionary resources for the Episcopal Church.

| Royal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Queen Kalama |

Queen Consort of Hawaiʻi 1856–1863 |

Succeeded by Queen Kapiʻolani |