Quedlinburg

| Quedlinburg | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Quedlinburg castle hill | ||

| ||

Quedlinburg | ||

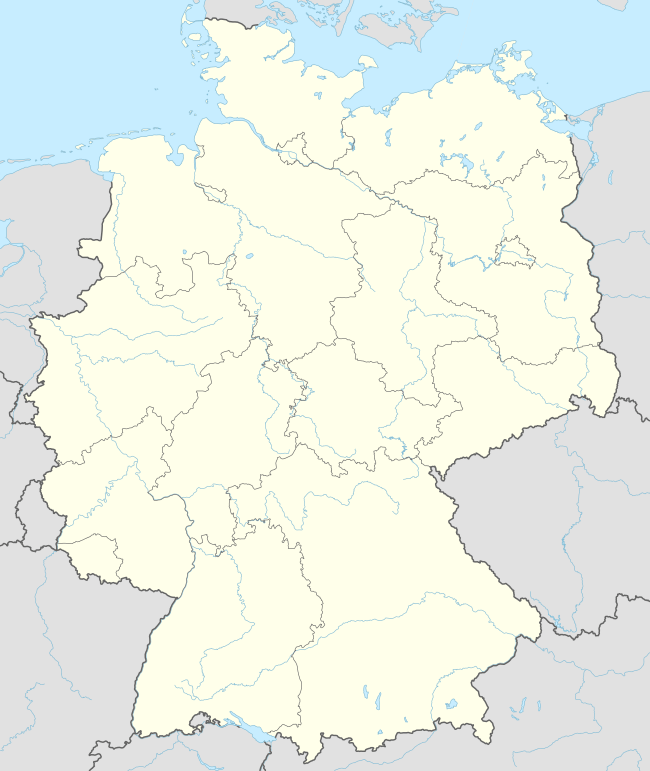

Location of Quedlinburg within Harz district  | ||

| Coordinates: 51°47′30″N 11°8′50″E / 51.79167°N 11.14722°ECoordinates: 51°47′30″N 11°8′50″E / 51.79167°N 11.14722°E | ||

| Country | Germany | |

| State | Saxony-Anhalt | |

| District | Harz | |

| Government | ||

| • Mayor | Frank Ruch (CDU) | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 120.42 km2 (46.49 sq mi) | |

| Population (2015-12-31)[1] | ||

| • Total | 24,555 | |

| • Density | 200/km2 (530/sq mi) | |

| Time zone | CET/CEST (UTC+1/+2) | |

| Postal codes | 06484, 06485 | |

| Dialling codes | 03946, 039485 | |

| Vehicle registration | HZ, HBS, QLB, WR | |

| Website | www.quedlinburg.de | |

Quedlinburg (German pronunciation: [ˈkveːdlɪnbʊʁk]) is a town situated just north of the Harz mountains, in the district of Harz in the west of Saxony-Anhalt, Germany. In 1994, the castle, church and old town were added to the UNESCO World Heritage List.

Quedlinburg has a population of more than 24,000. The town was the capital of the district of Quedlinburg until 2007, when the district was dissolved. Several locations in the town are designated stops along a scenic holiday route, the Romanesque Road.

History

The town of Quedlinburg is known to have existed since at least the early 9th century, when there was a settlement known as Gross Orden on the eastern bank of the River Bode. It was first mentioned as a town in 922 as part of a donation by King Henry the Fowler (Heinrich der Vogler). The records of this donation were held by the abbey of Corvey.

According to legend, Henry had been offered the German crown at Quedlinburg in 919 by Franconian nobles, giving rise to the town being called the "cradle of the German Reich".[2]:85

After Henry's death in 936, his widow Saint Matilda founded a religious community for women ("Frauenstift") on the castle hill, where daughters of the higher nobility were educated. The main task of this collegiate foundation, Quedlinburg Abbey, was to pray for the memory of King Henry and the rulers who came after him. The Annals of Quedlinburg were also compiled there. The first abbess was Matilda, a granddaughter of King Henry and St. Matilda.

The Quedlinburg castle complex, founded by King Henry I and built up by Emperor Otto I in 936, was an imperial Pfalz of the Saxon emperors. The Pfalz, including the male convent, was in the valley, where today the Roman Catholic Church of St. Wiperti is situated, while the women's convent was located on the castle hill.

In 973, shortly before the death of Emperor Otto I, a Reichstag (Imperial Convention) was held at the imperial court in which Mieszko, duke of Poland, and Boleslav, duke of Bohemia, as well as numerous other nobles from as far away as Byzantium and Bulgaria, gathered to pay homage to the emperor. On the occasion, Otto the Great introduced his new daughter-in-law Theophanu, a Byzantine princess whose marriage to Otto II brought hope for recognition and continued peace between the rulers of the Eastern and Western empires.

In 994, Otto III granted the right of market, tax, and coining, and established the first market place to the north of the castle hill.

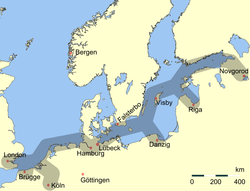

The town became a member of the Hanseatic League in 1426. Quedlinburg Abbey frequently disputed the independence of the town, which sought the aid of the Bishopric of Halberstadt. In 1477, Abbess Hedwig, aided by her brothers Ernest and Albert, broke the resistance of the town and expelled the bishop's forces. Quedlinburg was forced to leave the Hanseatic League and was subsequently protected by the Electorate of Saxony. Both town and abbey converted to Lutheranism in 1539 during the Protestant Reformation.

| Collegiate Church, Castle, and Old Town of Quedlinburg | |

|---|---|

| Name as inscribed on the World Heritage List | |

|

South of the castle hill: Schlossmühle | |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | iv |

| Reference | 535 |

| UNESCO region | Europe and North America |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 1994 (18th Session) |

In 1697, Elector Frederick Augustus I of Saxony sold his rights to Quedlinburg to Elector Frederick III of Brandenburg for 240,000 thalers. Quedlinburg Abbey contested Brandenburg-Prussia's claims throughout the 18th century, however. The abbey was secularized in 1802 during the German Mediatisation, and Quedlinburg passed to the Kingdom of Prussia as part of the Principality of Quedlinburg. Part of the Napoleonic Kingdom of Westphalia from 1807–13, it was included within the new Prussian Province of Saxony in 1815. In all this time, ladies ruled Quedlinburg as abbesses without "taking the veil"; they were free to marry. The last of these ladies was a Swedish princess, an early fighter for women's rights, Sofia Albertina.

During the Nazi regime, the memory of Henry I became a sort of cult, as Heinrich Himmler saw himself as the reincarnation of the "most German of all German" rulers. The collegiate church and castle were to be turned into a shrine for Nazi Germany. The Nazi Party tried to create a new religion. The cathedral was closed from 1938 and during the war. The local crematory was kept busy burning the victims of the Langenstein-Zwieberge concentration camp. Georg Ay was local party chief from 1931 until the end of the war. Liberation in 1945 brought back the Protestant bishop and the church bells, and the Nazi-style eagle was taken down from the tower.

Quedlinburg was administered within Bezirk Halle while part of the Communist East Germany from 1949 to 1990. It became part of the state of Saxony-Anhalt upon German reunification in 1990.

During Quedlinburg's Communist era restoration specialists from Poland were called in during the 1980s to carry out repairs on the old architecture. Today, Quedlinburg is a center of restoration of Fachwerk houses.

During the last months of World War II, the United States military had occupied Quedlinburg. In the 1980s, upon the death of one of the US military men, the theft of medieval art from Quedlinburg came to light.

Geography

Location

The town is located north of the Harz mountains, about 123 m above NHN. The nearest mountains reach 181 m above NHN. The largest part of the town is located in the western part of the Bode river valley. This river comes from the Harz mountains and flows into the river Saale, a tributary of the river Elbe. The municipal area of Quedlinburg is 120.42 square kilometres (46.49 square miles). Before the incorporation of the two (previously independent) municipalities of Gernrode and Bad Suderode in January 2014 it was only 78.14 square kilometres (30.17 square miles).

Neighbouring communities

|

Halberstadt | Oschersleben | Magdeburg |  |

| Blankenburg | |

Aschersleben | ||

| ||||

| | ||||

| Nordhausen | Sangerhausen | Halle |

Climate

Quedlinburg has a oceanic climate (Cfb) resulting from prevailing westerlies, blowing from the high-pressure area in the central Atlantic towards Scandinavia. Snowfall occurs almost every winter. January and February are the coldest months of the year, with an average temperature of 0.5 °C and 1.5 °C. July and August are the hottest months, with an average temperature of 17 °C (63 °F) and 18 °C (64 °F). The average annual precipitation is close to 438 mm with rain occurring usually from May to September. This precipitation is one of the lowest in Germany, which has an annual average close to 700 mm. In August 2010, Quedlinburg was the driest place in Germany, with only 72,4 l/m2.[3]

| Climate data for Quedlinburg | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 2 (36) |

4 (39) |

8 (46) |

13 (55) |

19 (66) |

21 (70) |

22 (72) |

23 (73) |

19 (66) |

13 (55) |

6 (43) |

3 (37) |

12.8 (54.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 0.5 (32.9) |

1.5 (34.7) |

4.5 (40.1) |

8.0 (46.4) |

13.5 (56.3) |

15.5 (59.9) |

17.0 (62.6) |

18.0 (64.4) |

14.0 (57.2) |

9.5 (49.1) |

3.5 (38.3) |

1.5 (34.7) |

8.92 (48.05) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −1 (30) |

−1 (30) |

1 (34) |

3 (37) |

8 (46) |

10 (50) |

12 (54) |

13 (55) |

9 (48) |

6 (43) |

1 (34) |

0 (32) |

5.1 (41.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 23 (0.91) |

22 (0.87) |

28 (1.1) |

38 (1.5) |

53 (2.09) |

57 (2.24) |

47 (1.85) |

54 (2.13) |

33 (1.3) |

27 (1.06) |

30 (1.18) |

26 (1.02) |

438 (17.25) |

| Average rainy days | 11 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 11 | 12 | 122 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 87 | 83 | 82 | 74 | 67 | 71 | 72 | 69 | 78 | 82 | 87 | 86 | 78.2 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 47.2 | 66.9 | 107.5 | 136.7 | 182.6 | 172.2 | 186.4 | 183.6 | 139.0 | 104.9 | 63.2 | 42.1 | 1,432.3 |

| Source #1: Deutscher Wetterdienst, Normalperiode 1961–1990[4] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: Zoover[5] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1786 | 8,382 | — |

| 1807 | 10,476 | +25.0% |

| 1820 | 11,507 | +9.8% |

| 1830 | 12,001 | +4.3% |

| 1840 | 13,431 | +11.9% |

| 1852 | 13,886 | +3.4% |

| 1861 | 14,835 | +6.8% |

| 1871 | 16,800 | +13.2% |

| 1880 | 18,437 | +9.7% |

| 1890 | 20,761 | +12.6% |

| 1900 | 23,378 | +12.6% |

| 1910 | 27,233 | +16.5% |

| 1919 | 28,190 | +3.5% |

| 1939 | 30,320 | +7.6% |

| 1946 | 35,142 | +15.9% |

| 1950 | 35,555 | +1.2% |

| 1955 | 33,125 | −6.8% |

| 1960 | 30,965 | −6.5% |

| 1965 | 30,840 | −0.4% |

| 1970 | 30,829 | −0.0% |

| 1975 | 29,711 | −3.6% |

| 1980 | 28,585 | −3.8% |

| 1985 | 29,394 | +2.8% |

| 1990 | 28,663 | −2.5% |

| 1995 | 25,844 | −9.8% |

| 2000 | 24,114 | −6.7% |

| 2005 | 22,607 | −6.2% |

| 2009* | 21,203 | −6.2% |

| Source:[6] | ||

Governance

The mayor is Frank Ruch (CDU).

Town twinning

Quedlinburg is twinned with:

Aulnoye-Aymeries, France, since 1961

Aulnoye-Aymeries, France, since 1961 Herford, Germany, since 1991

Herford, Germany, since 1991 Celle, Germany, since 1991

Celle, Germany, since 1991 Hameln, Germany, since 1991

Hameln, Germany, since 1991 Hann. Münden, Germany, since 1991

Hann. Münden, Germany, since 1991

Attractions

In the centre of the town, a wide selection of half-timbered buildings from at least five different centuries are to be found (including a 14th-century structure, one of Germany's oldest), while around the outer fringes of the old town are examples of Jugendstil buildings, dating from the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Since December 1994, the old town of Quedlinburg and the castle mount with the Stiftskirche (collegiate church) are listed as one of UNESCO's World Heritage Sites.[7] Quedlinburg is one of the best-preserved medieval and Renaissance towns in Europe, having escaped major damage in World War II.

In 2006, the Selke valley branch of the Harz Narrow Gauge Railways was extended to Quedlinburg from Gernrode, giving access to the historic steam narrow gauge railway, Alexisbad and the high Harz plateau.

The castle and Stifstkirche St. Servatius still dominate the town like in the early Middle Ages. The church is a prime example of German Romanesque style. The treasure of the church containing ancient Christian religious artifacts and books, was stolen by an American soldier but brought back to Quedlinburg in 1993 and is again on display here.

The former Stiftskirche St. Wiperti was established in 936 when the Kanonikerstift St. Wigpertus (of male canons) was moved from the castle hill to make way for what became Quedlinburg Abbey. The church was built at the location of the first, Ottonian, Royal palace at Quedlinburg. Around 1020, a three-aisled crypt was added to the basilica. The crypt, which survived all later alterations to the church, today is also a designated stop on the Romanesque Road.[2]:91

Infrastructure

Transport

Air

The nearest airports to Quedlinburg are Hannover, 120 kilometres (75 miles) northwest, and Leipzig/Halle Airport, 90 kilometres (56 miles) southeast. Much closer, but only served by a few airlines, is Magdeburg-Cochstedt. An airfield is located at Ballenstedt-Assmussstedt for general aviation.

Train

Regional trains run on the standard-gauge Magdeburg–Thale line by Deutsche Bahn and the private company Transdev connect Quedlinburg with Magdeburg, Thale, and Halberstadt.

In 2006, the Selke Valley branch of the Harz Narrow Gauge Railways was extended into Quedlinburg from Gernrode, giving access to the historic steam narrow-gauge railway, Alexisbad, and high Harz plateau.

Bus

Quedlinburg is connected by regional buses to the surrounding villages and small towns. Additionally, there are long distance buses to Berlin.

Notable people

- Dorothea Erxleben (1715-1762), was the first female medical doctor in Germany.[8]

- Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock (1724-1803), German poet and contemporary of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.

- Johann Gerhard (1582-1637), theologian, mean Denter representatives of Lutheran orthodoxy

- Wilhelm Homberg (1652-1715), naturalist, born apparently during a trip in Batavia / Jakarta, but parents living in Quedlinburg

- Johann Christoph Friedrich GutsMuths (1759-1839), father of German gymnastics

- Carl Ritter (1779-1859), founder of scientific Geography

- Julius Wolff (1834-1910), Freeman, poet and writer

- Gustav Albert Schwalbe (1844-1916), anatomist and anthropologist

- Carl Schroeder (1848-1935), cellist, composer, conductor and Hofkapellmeister

- Georg Ay (1900-1997), politician (NSDAP), membe of Reichstag 1933-1945

- Fritz Grasshoff (1913-1997), poet, painter, pop lyricist

- Bernhard Schrader (1931-2012), chemist, pioneer of experimental Raman - and infrared spectroscopy

- Peter Kramer (born 1933), physicist

- Leander Haussmann (born 1959), film and theater director (e.g. "Sun Alley (film) Sonnenallee", "Herr Lehmann", "NVA ")

- Petrik Sander (born 1960), football coach

- Petra Schersing (born Muller; 1965), sprinter and Olympic silver medalist

- Dagmar Hase (born 1969), swimmer and Olympic champion

References

- ↑ "Bevölkerung der Gemeinden – Stand: 31.12.2015" (PDF). Statistisches Landesamt Sachsen-Anhalt (in German).

- 1 2 Antz (ed.), Christian (2001). Strasse der Romanik (German). Verlag Janos Stekovics. ISBN 3-929330-89-X.

- ↑ Press release of the Deutsche Wetterdienst (pdf, German)

- ↑ "Deutscher Wetterdienst, Normalperiode 1961–1990" (in German). Deutscher Wetterdienst.

- ↑ "Zoover data by DWD". December 2010.

- ↑ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population" (PDF). Statistisches Landesamt Sachsen-Anhalt – Bevölkerung der Gemeinden nach Landkreisen; Stand: 31. Dez. 2009.

- ↑ Unesco World heritage list

- ↑ Schiebinger, L. (1990): "The Anatomy of Difference: Race and Sex in Eighteenth-Century Science" p. 399, Eighteenth Century Studies 23(3) pp. 387–405

Further reading

- Honan, William H. (1997). Treasure Hunt. A New York Times Reporter Tracks the Quedlinburg Hoard. New York: Fromm International Publishing Corporation. ISBN 0-88064-174-6.

- Kogelfranz, Siegfried; Willi A. Korte (1994). Quedlinburg – Texas and Back. Black Marketeering with Looted Art.

External links

-

Quedlinburg travel guide from Wikivoyage

Quedlinburg travel guide from Wikivoyage - The town's official website (German)

- UNESCO page on Quedlinburg

- Pictures and information about timber frame houses in Quedlinburg (German)

- The Quedlinberg Art Affair