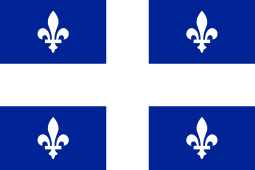

Quebec nationalism

Quebec nationalism or Québécois nationalism asserts that the Québécois people are an independent nation, separate from the rest of Canada, and promotes the unity of the Québécois people in the province of Quebec.

Canadien liberal nationalism

1534–1774

Canada was first a French colony. Jacques Cartier claimed it for France in 1534, and permanent French settlement began in 1608. It was part of New France, which constituted all French colonies in North America.[1] Up until 1760, Canadien nationalism had developed itself free of all external influences. However, during the Seven Years' War, the British army invaded the French colony as part of its North American strategy, winning a conclusive victory at the Battle of the Plains of Abraham. At the Treaty of Paris (1763), France agreed to abandon its claims in Canada in return for permanent French control of Guadeloupe. From the 1760s onward, Canadien nationalism developed within a British constitutional context. Despite intense pressure from outside Parliament, the British government drafted the Quebec Act which guaranteed Canadiens the restoration of French civil law; guaranteed the free practice of the Catholic faith; and returned the territorial extensions that they had enjoyed before the Treaty of Paris.[1] In effect, this "enlightened" action by leaders in the British Parliament allowed French Canada to retain its unique characteristics.[2][3] Although detrimental to Britain's relationship with the Thirteen Colonies, this has, in its contemporary assessment, been viewed as an act of appeasement and was largely effective at dissolving Canadien nationalism in the 18th century (especially considering the threat and proximity of American revolutionary ideology) yet it became less effective with the arrival of Loyalists after the revolutions.[4] With the Loyalists splitting the Province of Quebec into two identities; Upper Canada and Lower Canada, Canadiens were now labelled by the Loyalists as French Canadians.[1]

1800s–1880s

From 1776 to the late 1830s the world witnessed the creation of many new national states with the birth of the United States, the French Republic, Haiti, Paraguay, Argentina, Chile, Mexico, Brazil, Peru, Colombia, Belgium, Greece and others. Often accomplished militarily, these national independence movements occurred in the context of complex ideological and political struggles pitting European metropoles against their respective colonies, often assuming the dichotomy of monarchists against republicans. These battles succeeded in creating independent republican states in some regions of the world, but they failed in other places, such as Ireland, Upper Canada, Lower Canada, and Germany.

There is no consensus on the exact time of the birth of a national consciousness in French Canada. Some historians defend the thesis that it existed before the 19th century, because the Canadiens saw themselves as a people culturally distinct from the French even in the time of New France. The cultural tensions were indeed palpable between the governor of New France, the Canadian-born Pierre de Vaudreuil and the General Louis-Joseph de Montcalm, a Frenchman, during the French and Indian War. However, the use of the expression la nation canadienne (the Canadian nation) by French Canadians is a reality of the 19th century. The idea of a nation canadienne was supported by the liberal or professional class in Lower Canada: lawyers, notaries, librarians, accountants, doctors, journalists, and architects, among others.

A political movement for the independence of the Canadien people slowly took form following the enactment of the Constitutional Act of 1791. The Act of the British Parliament created two colonies, Lower Canada and Upper Canada, each of which had its own political institutions.[1] In Lower Canada, the French-speaking and Catholic Canadiens held the majority in the elected house of representatives, but were either a small minority or simply not represented in the appointed legislative and executive councils, both appointed by the Governor, representing the British Crown in the colony. Most of the members of the legislative council and the executive council were part of the British ruling class, composed of wealthy merchants, judges, military men, etc., supportive of the Tory party. From early 1800 to 1837, the government and the elected assembly were at odds on virtually every issue.

Under the leadership of Speaker Louis-Joseph Papineau, the Parti canadien (renamed Parti patriote in 1826) initiated a movement of reform of the political institutions of Lower Canada. The party's constitutional policy, summed up in the Ninety-Two Resolutions of 1834, called for the election of the legislative and executive councils.

The movement of reform gathered the support of the majority of the representatives of the people among Francophones but also among liberal Anglophones. A number of the prominent characters in the reformist movement were of British origin, for example John Neilson, Wolfred Nelson, Robert Nelson and Thomas Storrow Brown or of Irish extraction, Edmund Bailey O'Callaghan, Daniel Tracey and Jocquelin Waller.

Two currents existed within the reformists of the Parti canadien: a moderate wing, whose members were fond of British institutions and wished for Lower Canada to have a government more accountable to the elective house's representative and a more radical wing whose attachment to British institutions was rather conditional to this proving to be as good as to those of the neighbouring American republics.

The formal rejection of all 92 resolutions by the Parliament of Great Britain in 1837 led to a radicalization of the patriotic movement's actions. Louis-Joseph Papineau took the leadership of a new strategy which included the boycott of all British imports. During the summer, many popular gatherings (assemblées populaires) were organized to protest against the policy of Great Britain in Lower Canada. In November, Governor Archibald Acheson ordered the arrest of 26 leaders of the patriote movement, among whom Louis-Joseph Papineau and many other reformists were members of parliament. This instigated an armed conflict which developed into the Lower Canada Rebellion.

Following the repression of the insurrectionist movement of 1838, many of the most revolutionary nationalist and democratic ideas of the Parti patriote were discredited.

Ultramontane nationalism

1840s–1950s

Although it was still defended and promoted up until the beginning of the 20th century, the French-Canadian liberal nationalism born out of the American and French revolutions began to decline in the 1840s, gradually being replaced by both a more moderate liberal nationalism and the ultramontanism of the powerful Catholic clergy as epitomized by Lionel Groulx. In the 1920s–1950s, this form of traditionalist Catholic nationalism became known as clerico-nationalism

In opposition with the other nationalists, ultramontanes rejected the idea that the people are sovereign and that church and state should be absolutely separated. They accepted the authority of the British crown in Canada, defended its legitimacy, and preached obedience to the British ruler. For ultramontanes, the faith of Franco-Canadians was to survive by defending their Roman Catholic religion and the French language.

Contemporary Quebec nationalism

Understanding contemporary Quebec nationalism is difficult considering the ongoing debates on the political status of the province and its complex public opinion.[5][6] No political option (outright independence, sovereignty-association, constitutional reforms, or signing on to the present Canadian constitution) has achieved decisive majority support and contradictions remain within the Quebec polity.

One debated subject that has often made the news is whether contemporary Quebec nationalism is still "ethnic" or if it is "linguistic" or "territorial".

The notion of "territorial nationalism" (promoted by all Quebec premiers since Jean Lesage) gathers the support of the majority of the sovereigntists and essentially all Quebec federalist nationalists. Debates on the nature of Quebec's nationalism are currently going on and various intellectuals from Quebec or other parts of Canada have published works on the subject, notably Will Kymlicka, professor of philosophy at Queen's University and Charles Blattberg and Michel Seymour, both professors at the Université de Montréal.

People who feel that Quebec nationalism is still ethnic have often expressed their opinion that the sentiments of Quebec's nationalists are insular and parochial and concerned with preserving a "pure laine" population of white francophones within the province. These accusations have always been vigorously denounced by Quebec nationalists of all sides, and such sentiments are generally considered as unrepresentative of the intellectual and mainstream political movements in favour of a wider independence for Quebec, seeing the movement as a multi-ethnic cause. However, then Premier of Quebec Jacques Parizeau, commenting on the failure of the 1995 Quebec referendum said "It is true, it is true that we were beaten, but in the end, by what? By money and ethnic votes, essentially." ("C'est vrai, c'est vrai qu'on a été battus, au fond, par quoi? Par l'argent puis des votes ethniques, essentiellement.")

People who feel that Quebec nationalism is linguistic have often expressed their opinion that Quebec nationalism includes a multi-ethnic or multicultural French-speaking majority (either as mother tongue or first language used in public).

There is little doubt that the post-1950s era witnessed an awakening of Quebecers' self-identity. The rural, conservative and Catholic Quebec of the 19th and early 20th centuries has given way to a confident, cosmopolitan society that has many attributes of a modern, internationally recognized community with a unique culture worth preserving.

The cultural character of Quebec nationalism has been affected by changes in the cultural identity of the province/nation more generally. Since the 1960s, these changes have included the secularism and other traits associated with the Quiet Revolution.

Recognition of the nation by Ottawa

On October 21, 2006, during the General Special Council of the Quebec wing of the Liberal Party of Canada initiated a national debate by adopting with more than 80% support a resolution calling on the Government of Canada to recognize the Quebec nation within Canada. A month later, the said resolution was taken to Parliament first by the Bloc Québécois, then by the Prime Minister of Canada, Stephen Harper. On November 27, 2006, the Canadian House of Commons passed a motion recognizing that the "Québécois form a nation within a united Canada".[7]

See also

- Canadian nationalism

- French nationalism

- History of Quebec

- Lists of active separatist movements

- Nationalism

- Partition of Quebec

- Politics of Canada

- Politics of Quebec

- Quebec federalist ideology

- Quebec sovereignty movement

- Quebec referendum, 1980

- Quebec referendum, 1995

- Quiet Revolution

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 "Canada". Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs. Retrieved 2011-12-13. See drop-down essay on "Early European Settlement and the Formation of the Modern State"

- ↑ Philip Lawson, The Imperial Challenge: Quebec and Britain in the Age of the American Revolution (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen's UP, 1989).

- ↑ Gary Caldwell, "The Men Who Saved Quebec" Andrew Cusack.com (2001)

- ↑ Nancy Brown Foulds. "Quebec Act". Thecanadianencyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2011-04-13.

- ↑ "Sovereignty support drops after Tory win: poll". CTV.ca. 2006-02-01. Archived from the original on 2006-02-19. Retrieved 2011-04-13.

- ↑ "Polls May Show Separatism Rising". Thecanadianencyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2011-04-13.

- ↑ "La Chambre reconnaît la nation québécoise". Radio-canada.ca. Retrieved 2011-04-13.

References

- Claude Bélanger Quebec nationalism

In English

Books

- Fabrice Rivault & Hervé Rivet (2008). “The Quebec Nation: From Informal Recognition to Enshrinement in the Constitution” in Reconquering Canada: Quebec Federalists Speak Up for Change, Edited by André Pratte, Douglas & McIntyre, Toronto, 344 p. (ISBN 978-1-55365-413-1) (link)

- Henderson, Ailsa (2007). Hierarchies of Belonging: National Identity and Political Culture in Scotland and Quebec, Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 250 p. (ISBN 978-0-7735-3268-7)

- McEwen, Nicola (2006). Nationalism and the State: Welfare and Identity in Scotland and Quebec, Brussels: P.I.E.-Peter Lang, 212 p. (ISBN 90-5201-240-7)

- Seymour, Michel (2004). Fate of the Nation State, Montreal: McGill-Queen's Press, 432 p. (ISBN 0773526862) (excerpt)

- Gagnon, Alain (2004). Québec. State and Society, Broadview Press, 500 p. (ISBN 1551115794) (excerpt)

- Cook, Ramsay (2003). Watching Quebec. Selected Essays, Montreal, McGill-Queen's Press, 225 p. (ISBN 0773529195) (excerpt)

- Mann, Susan (2002). The Dream of Nation: A Social and Intellectual History of Quebec, McGill-Queen's University Press; 2nd edition, 360 p. (ISBN 077352410X) (excerpt)

- Requejo, Ferran (2001). Democracy and National Pluralism, 182 p. (ISBN 0415255775) (excerpt)

- Venne, Michel (2001). Vive Quebec! New Thinking and New Approaches to the Quebec Nation, James Toronto: Lorimer & Company, 221 p. (ISBN 1550287346) (excerpt)

- Poliquin, Daniel (2001). In the Name of the Father: An Essay on Quebec nationalism, Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 222 p. (ISBN 1-55054-858-1)

- Barreto, Amílcar Antonio (1998). Language, Elites, and the State. Nationalism in Puerto Rico and Quebec, Greenwood Publishing Group, 165 p. (ISBN 0275961834) (excerpt)

- Keating, Michael (1996). Nations Against the State: The New Politics of Nationalism in Quebec, Catalonia, and Scotland, St. Martins Press, 260 p. (ISBN 0312158173)

- Carens, Joseph H., ed. (1995), Is Quebec Nationalism Just?: Perspectives from Anglophone Canada, Montreal, McGill-Queen's University Press, 225 p. (ISBN 0773513426) (excerpt)

- Berberoglu, Berch, ed., (1995). The National Question: Nationalism, Ethnic Conflict, and Self-Determination in the 20th Century, Temple University Press, 329 p. (ISBN 1566393434) (excerpt)

- Gougeon, Gilles (1994). A History of Quebec Nationalism, Lorimer, 118 p. (ISBN 155028441X) (except)

Newspapers and journals

- Rocher, François. "The Evolving Parameters of Quebec Nationalism", in JMS: International Journal on Multicultural Societies. 2002, vol. 4, no.1, pp. 74–96. UNESCO. (ISSN 1817-4574) (online)

- Venne, Michel. "Re-thinking the Quebec nation", in Policy Options, January–February 2000, pp. 53–60 (online)

- Kymlicka, Will. "Quebec: a modern, pluralist, distinct society", in Dissent, American Multiculturalism in the International Arena, Fall 1998, p. 73–79 (archived version)

- Couture, Jocelyne, Kai Nielsen, and Michel Seymour (ed). "Rethinking Nationalism", in Canadian Journal of Philosophy, Supplementary Volume XXII, 1996, 704 p. (ISBN 0919491227)

In French

Books

- Bock-Côté, Mathieu (2007). La dénationalisation tranquille : mémoire, identité et multiculturalisme dans le Québec postréférendaire, Montréal: Boréal, 211 p. (ISBN 978-2-7646-0564-6)

- Ryan, Pascale (2006). Penser la nation. La ligue d'action nationale 1917–1960, Montréal: Leméac, 324 p. (ISBN 2760905993)

- Montpetit, Édouard (2005). Réflexions sur la question nationale: Édouard Montpetit; textes choisis et présentés par Robert Leroux, Saint-Laurent: Bibliothèque québécoise, 181 p. (ISBN 2-89406-259-1)

- Lamonde, Yvan (2004). Histoire sociale des idées au Québec, 1896–1929, Montréal: Éditions Fides, 336 p. (ISBN 2-7621-2529-4)

- Bock, Michel (2004). Quand la nation débordait les frontières. Les minorités françaises dans la pensée de Lionel Groulx, Montréal: Hurtubise HMH, 452 p.

- Bellavance, Marcel (2004). Le Québec au siècle des nationalités. Essai d’histoire comparée, Montréal: VLB, 250 p.

- Bouchard, Gérard (2004). La pensée impuissante : échecs et mythes nationaux canadiens-français, 1850–1960, Montréal: Boréal, 319 p. (ISBN 2-7646-0345-2)

- Bouchard, Catherine (2002). Les nations québécoises dans l'Action nationale : de la décolonisation à la mondialisation, Sainte-Foy: Presses de l'Université Laval, 146 p. (ISBN 2-7637-7847-X)

- Sarra-Bournet, Michel ed., (2001). Les nationalismes au Québec, du XIXe au XXIe siècle, Québec: Presses de L’Université Laval, 2001

- Diane, Lamoureux (2001). L'amère patrie : féminisme et nationalisme dans le Québec contemporain, Montréal: Éditions du Remue-ménage (ISBN 2-89091-182-9)

- Monière, Denis (2001). Pour comprendre le nationalisme au Québec et ailleurs, Montréal: Presses de l'Université de Montréal 148 pé (ISBN 2-7606-1811-0)

- Denise Helly and Nicolas Van Schendel (2001). Appartenir au Québec : Citoyenneté, nation et société civile : Enquête à Montréal, 1995, Québec: Les Presses de l'Université Laval (editor)

- Brière, Marc (2001). Le Québec, quel Québec? : dialogues avec Charles Taylor, Claude Ryan et quelques autres sur le libéralisme et le nationalisme québécois, Montréal: Stanké, 325 p. (ISBN 2-7604-0805-1)

- Paquin, Stéphane (2001). La revanche des petites nations : le Québec, l'Écosse et la Catalogne face à la mondialisation, Montréal: VLB, 219 p. (ISBN 2-89005-775-5)

- Lamonde, Yvan (2000). Histoire sociale des idées au Québec, 1760–1896, Montréal: Éditions Fides, 576 p. (ISBN 2-7621-2104-3) (online)

- Venne, Michel, ed., (2000). Penser la nation québécoise, Montréal: Québec Amérique, Collection Débats

- Brière, Marc (2000). Point de départ! : essai sur la nation québécoise, Montréal : Hurtubise HMH, 222 p. (ISBN 2-89428-427-6)

- Seymour, Michel (1999). La nation en question, L'Hexagone,

- Seymour, Michel, ed. (1999). Nationalité, citoyenneté et solidarité, Montréal: Liber, 508 p. (ISBN 2-921569-68-X)

- Sarra-Bournet, Michel ed., (1998). Le pays de tous les Québécois. Diversité culturelle et souveraineté, Montréal: VLB Éditeur, 253 p.

- Martel, Marcel (1997). Le deuil d'un pays imaginé : rêves, luttes et déroute du Canada français : les rapports entre le Québec et la francophonie canadienne, 1867–1975, Ottawa: Presses de l'Université d'Ottawa, 203 p. (ISBN 2-7603-0439-6)

- Keating, Michael (1997). Les défis du nationalisme moderne : Québec, Catalogne, Écosse, Montréal: Presses de l'Université de Montréal, 296 p. (ISBN 2-7606-1685-1)

- Bourque, Gilles (1996). L'identité fragmentée : nation et citoyenneté dans les débats constitutionnels canadiens, 1941–1992, Saint-Laurent: Fides, 383 p. (ISBN 2-7621-1869-7)

- Moreau, François (1995). Le Québec, une nation opprimée, Hull : Vents d'ouest, 181 p (ISBN 2-921603-23-3)

- Ignatieff, Michael (1993). Blood & belonging : journeys into the new nationalism, Toronto : Viking, 201 p. (ISBN 0670852694)

- Gougeon, Gilles (1993). Histoire du nationalisme québécois. Entrevues avec sept spécialistes, Québec: VLB Éditeur

- Roy, Fernande (1993). Histoire des idéologies au Québec aux XIXe et XXe siècles, Montréal: Boréal, 128 p. (ISBN 2890525880)

- Balthazar, Louis. "L'évolution du nationalisme québécois", in Le Québec en jeu, ed. Gérard Daigle and Guy Rocher, pp. 647 à 667, Montréal: Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal, 1992, 812 p.

Newspapers and journals

- Robitaille, Antoine. "La nation, pour quoi faire?", in Le Devoir, November 25, 2006

- Gueydan-Lacroix, Saël. "Le nationalisme au Canada anglais : une réalité cachée", in L'Agora, April 10, 2003

- Courtois, Stéphane. "Habermas et la question du nationalisme : le cas du Québec", in Philosophiques, vol. 27, no 2, Autumn 2000

- Seymour, Michel. "Un nationalisme non fondé sur l'ethnicité", in Le Devoir, 26–27 April 1999

- Kelly, Stéphane. "De la laine du pays de 1837, la pure et l'impure", in L'Encyclopédie de l'Agora, Cahiers d'histoire du Québec au XXe siècle, no 6, 1996

- Beauchemin, Jacques. "Nationalisme québécois et crise du lien social", in Cahiers de recherche sociologique, n° 25, 1995, pp. 101–123. Montréal: Département de sociologie, UQAM.

- Dufresne, Jacques. "La cartographie du génome nationaliste québécois", dans L'Agora, vol. 1, no. 10, July/August 1994.

- Seymour, Michel. "Une nation peut-elle se donner la constitution de son choix?", in Philosophiques, Numero Special, Vol. 19, No. 2 (Autumn 1992)

- Unknown. "L'ultramontanisme", in Les Patriotes de 1837@1838, May 20, 2000

- Roy-Blais, Caroline. "La montée du pouvoir clérical après l’échec patriote", in Les Patriotes de 1837@1838, 2006-12-03

Further reading

- Angers, François-Albert (1969). Pour orienter nos libertés (in French). Montréal: Fides. p. 280.

- Arnaud, Nicole (1978). Nationalism and the National Question. Montreal: Black Rose Books. p. 133. ISBN 0-919618-45-6.

- Behiels, Michael Derek (1985). Prelude to Quebec's Quiet Revolution: Liberalism versus Neo-Nationalism, 1945–1960. Kingston, Ontario: McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 366. ISBN 0-7735-0424-9.

- Bernard, Jean-Paul (1973). Les idéologies québécoises au 19e siècle (in French). Montréal: Les Éditions du Boréal Express.

- Bernier, Gérald & Daniel Salée (1992). The Shaping of Québec Politics and Society: Colonialism, Power, and the Transition to Capitalism in the 19th Century. Washington: Crane Russak. p. 170. ISBN 0-8448-1697-3.

- Bourque, Gilles (1970). Classes sociales et question nationale au Québec, 1760–1840 (in French). Montréal: Editions Parti pris. p. 350.

- Bouthillette, Jean (1972). Le Canadien français et son double (in French). Ottawa: Éditions de l'Hexagone. p. 101.

- Brunet, Michel (1969). Québec, Canada anglais; : deux itinéraires, un affrontement (in French). Montréal: Hurtubise HMH. p. 309.

- Cameron, David (1974). Nationalism, Self-Determination and the Quebec Question. Toronto: Macmillan of Canada. p. 177. ISBN 0-7705-0970-3.

- Clift, Dominique (1981). Le Déclin du nationalisme au Québec (in French). Montréal: Libre Expression. p. 195. ISBN 2-89111-062-5.

- Cook, Ramsay (1969). French-Canadian Nationalism; An Anthology. Toronto: Macmillan of Canada. p. 336.

- Crean, Susan (1983). Two Nations: An Essay on the Culture and Politics of Canada and Quebec in a World of American Preeminence. Toronto: J. Lorimer. p. 167. ISBN 0-88862-381-X.

- Cyr, François (1981). Eléments d'histoire de la FTQ : la FTQ et la question nationale (in French). Laval: Editions coopératives A. Saint-Martin. p. 205. ISBN 2-89035-045-2.

- D'Allemagne, André (1966). Le Colonialisme au Québec (in French). Montréal: les Editions R.-B. p. 191.

- Eid, Nadia F. (1978). Le clergé et le pouvoir politique au Québec, une analyse de l’idéologie ultramontaine au milieu du XIXe siècle (in French). HMH: Cahiers du Québec, Collection Histoire. p. 318.

- Feldman, Elliot J. & Neil Nevitte (1979). The future of North America: Canada, the United States and Quebec nationalism. Cambridge, Mass: Center for International Affairs, Harvard University. p. 378. ISBN 0-87674-045-X.

- Gauvin, Bernard (1981). Les communistes et la question nationale au Québec : sur le Parti communiste du Canada de 1921 à 1938 (in French). Montréal: Les Presses de l'Unité. p. 151.

- Grube, John (1981). Bâtisseur de pays : la pensée de François-Albert Angers. Étude sur le nationalisme au Québec (in French). Montréal: Editions de l'Action nationale. p. 256. ISBN 2-89070-000-3.

- Guindon, Hubert (1988). Quebec Society: Tradition, Modernity, and Nationhood. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. 180. ISBN 0-8020-2645-1.

- Handler, Richard (1988). Nationalism and the politics of culture in Quebec. Madison, WI, USA: University of Wisconsin Press. p. 217. ISBN 0-299-11510-0.

- Jones, Richard (1967). Community in crisis : French-Canadian nationalism in perspective. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart Limited. p. 192.

- Keating, Michael (2001). Plurinational Democracy: Stateless Nations in a Post-sovereignty Era. Oxford University Press. p. 197. ISBN 0-19-924076-0.

- Laurendeau, André (1935). Notre nationalisme (in French). Montréal: imprimé au "Devoir". p. 52.

- Laurin-Frenette, Nicole (1978). Production de l'Etat et formes de la nation (in French). Montréal: Nouvelle Optique. p. 176. ISBN 0-88579-021-9.

- Léon, Dion (1975). Nationalismes et politique au Québec (in French). Montréal: Les Éditions Hurbubise HMH. p. 177.

- Lisée, Jean-François (1990). In the eye of the eagle. Toronto: Harper Collins. ISBN 0-00-637636-3.

- Mann, Susan (1975). Action Française: French Canadian nationalism in the twenties. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. 57. ISBN 0-8020-5320-3.

- Mascotto, Jacques & Pierre-Yves Soucy (1980). Démocratie et nation : néo-nationalisme, crise et formes du pouvoir (in French). Laval: Editions coopératives A. Saint- Martin. p. 278. ISBN 2-89035-016-9.

- Milner, Henry and Sheilagh Hodgins Milner (1973). The Decolonization of Quebec: An Analysis of Left-Wing Nationalism. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart. p. 257. ISBN 0-7710-9902-9.

- Monet, Jacques (1969). The Last Cannon Shot; A Study of French-Canadian Nationalism, 1837–1850. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. 422.

- Monière, Denis (1977). Le développement des idéologies au Québec, des origines à nos jours (in French). Québec/Amérique. p. 381. ISBN 0-88552-036-X.

- Morin, Wilfrid (1960). L'indépendance du Québec : le Québec aux québécois! (in French). Montréal: Alliance laurentienne. p. 253.

- Morin, Wilfrid (1938). Nos droits à l'indépendance politique (in French). Paris: Guillemot et de Lamothe. p. 253.

- Newman, Saul (1996). Ethnoregional Conflict in Democracies: Mostly Ballots, Rarely Bullets. Greenwood Publishing. p. 279. ISBN 0-313-30039-9.

- O'Leary, Dostaler (1965). L'Inferiority complex (in French). Montréal: imprimé au "Devoir". p. 27.

- Pellerin, Jean (1969). Lettre aux nationalistes québécois (in French). Montréal: Éditions du Jour. p. 142.

- Pris, Parti (1967). Les Québécois (in French). Paris: F. Maspero. p. 300.

- Quinn, Herbert Furlong (1963). The Union Nationale: A Study in Quebec Nationalism. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. 249. ISBN 0-8020-6040-4.

- Scott, Francis Reginald (1964). Quebec States Her Case: Speeches and Articles from Quebec in the Years of Unrest. Toronto: Macmillan of Canada. p. 165.

- See, Katherine O'Sullivan (1986). First World Nationalisms: Class and Ethnic politics in Northern Ireland and Quebec. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 215. ISBN 0-226-74416-7.

- Tremblay, Marc-Adélard (1983). L'Identité québécoise en péril (in French). Sainte-Foy: Editions Saint-Yves. p. 287. ISBN 2-89034-009-0.

- De Nive Voisine; Jean Hamelin; Philippe Sylvain (1985). Les Ultramontains canadiens-français (in French). Montréal: Boréal express. p. 347. ISBN 2-89052-123-0.

- World Peace Foundation de Boston and Le Centre d'études canadiennes-françaises de McGill (1975). Le nationalisme québécois à la croisée des chemins (in French). Québec: Centre québécois de relations internationales. p. 375.