Quantum teleportation

Quantum teleportation is a process by which quantum information (e.g. the exact state of an atom or photon) can be transmitted (exactly, in principle) from one location to another, with the help of classical communication and previously shared quantum entanglement between the sending and receiving location. Because it depends on classical communication, which can proceed no faster than the speed of light, it cannot be used for faster-than-light transport or communication of classical bits. While it has proven possible to teleport one or more qubits of information between two (entangled) atoms,[1][2][3] this has not yet been achieved between molecules or anything larger.

Although the name is inspired by the teleportation commonly used in fiction, there is no relationship outside the name, because quantum teleportation concerns only the transfer of information. Quantum teleportation is not a form of transport, but of communication; it provides a way of transporting a qubit from one location to another, without having to move a physical particle along with it.

The seminal paper[4] first expounding the idea of quantum teleportation was published by C. H. Bennett, G. Brassard, C. Crépeau, R. Jozsa, A. Peres and W. K. Wootters in 1993.[5] Since then, quantum teleportation was first realized with single photons [6] and later demonstrated with various material systems such as atoms, ions, electrons and superconducting circuits. The record distance for quantum teleportation is 143 km (89 mi).[7]

In October 2015, scientists from the Kavli Institute of Nanoscience of the Delft University of Technology reported that the quantum nonlocality phenomenon is supported at the 96% confidence level based on a "loophole-free Bell test" study.[8][9] These results were confirmed by two studies with statistical significance over 5 standard deviations which were published in December 2015.[10][11]

Non-technical summary

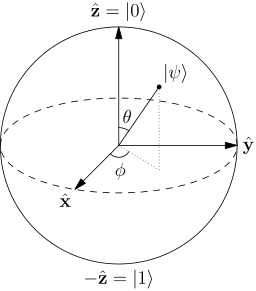

In matters relating to quantum or classical information theory, it is convenient to work with the simplest possible unit of information, the two-state system. In classical information this is a bit, commonly represented using one or zero (or true or false). The quantum analog of a bit is a quantum bit, or qubit. Qubits encode a type of information, called quantum information, which differs sharply from "classical" information. For example, quantum information can be neither copied (the no-cloning theorem) nor destroyed (the no-deleting theorem).

Quantum teleportation provides a mechanism of moving a qubit from one location to another, without having to physically transport the underlying particle that a qubit is normally attached to. Much like the invention of the telegraph allowed classical bits to be transported at high speed across continents, quantum teleportation holds the promise that one day, qubits could be moved likewise. However, as of 2013, only photons and single atoms have been employed as information bearers.

The movement of qubits does require the movement of "things"; in particular, the actual teleportation protocol requires that an entangled quantum state or Bell state be created, and its two parts shared between two locations (the source and destination, or Alice and Bob). In essence, a certain kind of "quantum channel" between two sites must be established first, before a qubit can be moved. Teleportation also requires a classical information link to be established, as two classical bits must be transmitted to accompany each qubit. The need for such links may, at first, seem disappointing; however, this is not unlike ordinary communications, which requires wires, radios or lasers. What's more, Bell states are most easily shared using photons from lasers, and so teleportation could be done, in principle, through open space.

The quantum states of single atoms have been teleported.[1][2][3] An atom consists of several parts: the qubits in the electronic state or electron shells surrounding the atomic nucleus, the qubits in the nucleus itself, and, finally, the electrons, protons and neutrons making up the atom. Physicists have teleported the qubits encoded in the electronic state of atoms; they have not teleported the nuclear state, nor the nucleus itself. It is therefore false to say "an atom has been teleported". It has not. The quantum state of an atom has. Thus, performing this kind of teleportation requires a stock of atoms at the receiving site, available for having qubits imprinted on them. The importance of teleporting nuclear state is unclear: nuclear state does affect the atom, e.g. in hyperfine splitting, but whether such state would need to be teleported in some futuristic "practical" application is debatable.

An important aspect of quantum information theory is entanglement, which imposes statistical correlations between otherwise distinct physical systems. These correlations hold even when measurements are chosen and performed independently, out of causal contact from one another, as verified in Bell test experiments. Thus, an observation resulting from a measurement choice made at one point in spacetime seems to instantaneously affect outcomes in another region, even though light hasn't yet had time to travel the distance; a conclusion seemingly at odds with Special relativity (EPR paradox). However such correlations can never be used to transmit any information faster than the speed of light, a statement encapsulated in the no-communication theorem. Thus, teleportation, as a whole, can never be superluminal, as a qubit cannot be reconstructed until the accompanying classical information arrives.

The proper description of quantum teleportation requires a basic mathematical toolset, which, although complex, is not out of reach of advanced high-school students, and indeed becomes accessible to college students with a good grounding in finite-dimensional linear algebra. In particular, the theory of Hilbert spaces and projection matrixes is heavily used. A qubit is described using a two-dimensional complex number-valued vector space (a Hilbert space); the formal manipulations given below do not make use of anything much more than that. Strictly speaking, a working knowledge of quantum mechanics is not required to understand the mathematics of quantum teleportation, although without such acquaintance, the deeper meaning of the equations may remain quite mysterious.

Protocol

The prerequisites for quantum teleportation are a qubit that is to be teleported, a conventional communication channel capable of transmitting two classical bits (i.e., one of four states), and means of generating an entangled EPR pair of qubits, transporting each of these to two different locations, A and B, performing a Bell measurement on one of the EPR pair qubits, and manipulating the quantum state of the other of the pair. The protocol is then as follows:

- An EPR pair is generated, one qubit sent to location A, the other to B.

- At location A, a Bell measurement of the EPR pair qubit and the qubit to be teleported (the quantum state ) is performed, yielding one of four measurement outcomes, which can be encoded in two classical bits of information. Both qubits at location A are then discarded.

- Using the classical channel, the two bits are sent from A to B. (This is the only potentially time-consuming step after step 1, due to speed-of-light considerations.)

- As a result of the measurement performed at location A, the EPR pair qubit at location B is in one of four possible states. Of these four possible states, one is identical to the original quantum state , and the other three are closely related. Which of these four possibilities actually obtains is encoded in the two classical bits. Knowing this, the qubit at location B is modified in one of three ways, or not at all, to result in a qubit identical to , the qubit that was chosen for teleportation.

Experimental results and records

Work in 1998 verified the initial predictions,[12] and the distance of teleportation was increased in August 2004 to 600 meters, using optical fiber.[13] Subsequently, the record distance for quantum teleportation has been gradually increased to 16 km,[14] then to 97 km,[15] and is now 143 km (89 mi), set in open air experiments done between two of the Canary Islands.[7] There has been a recent record set (as of September 2015) using superconducting nanowire detectors that reached the distance of 102 km (63 mi) over optical fiber.[16] For material systems, the record distance is 21 m.[17]

A variant of teleportation called "open-destination" teleportation, with receivers located at multiple locations, was demonstrated in 2004 using five-photon entanglement.[18] Teleportation of a composite state of two single photons has also been realized.[19] In April 2011, experimenters reported that they had demonstrated teleportation of wave packets of light up to a bandwidth of 10 MHz while preserving strongly nonclassical superposition states.[20][21] In August 2013, the achievement of "fully deterministic" quantum teleportation, using a hybrid technique, was reported.[22] On 29 May 2014, scientists announced a reliable way of transferring data by quantum teleportation. Quantum teleportation of data had been done before but with highly unreliable methods.[23][24] On 26 February 2015, scientists reported the first experiment teleporting multiple degrees of freedom of a quantum particle.[25]

Researchers have also successfully used quantum teleportation to transmit information between clouds of gas atoms, notable because the clouds of gas are macroscopic atomic ensembles.[26][27]

Formal presentation

There are a variety of ways in which the teleportation protocol can be written mathematically. Some are very compact but abstract, and some are verbose but straightforward and concrete. The presentation below is of the latter form: verbose, but has the benefit of showing each quantum state simply and directly. Later sections review more compact notations.

The teleportation protocol begins with a quantum state or qubit , in Alice's possession, that she wants to convey to Bob. This qubit can be written generally, in bra–ket notation, as:

The subscript C above is used only to distinguish this state from A and B, below. The protocol requires that Alice and Bob share a maximally entangled state. This state is fixed in advance, by mutual agreement between Alice and Bob, and can be any one of the four Bell states shown. It does not matter which one.

- ,

- ,

- ,

- .

In the following, assume that Alice and Bob share the state Alice obtains one of the particles in the pair, with the other going to Bob. (This is implemented by preparing the particles together and shooting them to Alice and Bob from a common source.) The subscripts A and B in the entangled state refer to Alice's or Bob's particle.

At this point, Alice has two particles (C, the one she wants to teleport, and A, one of the entangled pair), and Bob has one particle, B. In the total system, the state of these three particles is given by

Alice will then make a local measurement in the Bell basis (i.e. the four Bell states) on the two particles in her possession. To make the result of her measurement clear, it is best to write the state of Alice's two qubits as superpositions of the Bell basis. This is done by using the following general identities, which are easily verified:

and

One applies these identities with A and C subscripts. The total three particle state, of A, B and C together, thus becomes the following four-term superposition:

The above is just a change of basis on Alice's part of the system. No operation has been performed and the three particles are still in the same total state. The actual teleportation occurs when Alice measures her two qubits A,C, in the Bell basis

- .

Experimentally, this measurement may be achieved via a series of laser pulses directed at the two particles. Given the above expression, evidently the result of Alice's (local) measurement is that the three-particle state would collapse to one of the following four states (with equal probability of obtaining each):

Alice's two particles are now entangled to each other, in one of the four Bell states, and the entanglement originally shared between Alice's and Bob's particles is now broken. Bob's particle takes on one of the four superposition states shown above. Note how Bob's qubit is now in a state that resembles the state to be teleported. The four possible states for Bob's qubit are unitary images of the state to be teleported.

The result of Alice's Bell measurement tells her which of the above four states the system is in. She can now send her result to Bob through a classical channel. Two classical bits can communicate which of the four results she obtained.

After Bob receives the message from Alice, he will know which of the four states his particle is in. Using this information, he performs a unitary operation on his particle to transform it to the desired state :

- If Alice indicates her result is , Bob knows his qubit is already in the desired state and does nothing. This amounts to the trivial unitary operation, the identity operator.

- If the message indicates , Bob would send his qubit through the unitary quantum gate given by the Pauli matrix

to recover the state.

- If Alice's message corresponds to , Bob applies the gate

to his qubit.

- Finally, for the remaining case, the appropriate gate is given by

Teleportation is thus achieved. The above-mentioned three gates correspond to rotations of π radians (180°) about appropriate axes (X, Y and Z).

Some remarks:

- After this operation, Bob's qubit will take on the state , and Alice's qubit becomes an (undefined) part of an entangled state. Teleportation does not result in the copying of qubits, and hence is consistent with the no cloning theorem.

- There is no transfer of matter or energy involved. Alice's particle has not been physically moved to Bob; only its state has been transferred. The term "teleportation", coined by Bennett, Brassard, Crépeau, Jozsa, Peres and Wootters, reflects the indistinguishability of quantum mechanical particles.

- For every qubit teleported, Alice needs to send Bob two classical bits of information. These two classical bits do not carry complete information about the qubit being teleported. If an eavesdropper intercepts the two bits, she may know exactly what Bob needs to do in order to recover the desired state. However, this information is useless if she cannot interact with the entangled particle in Bob's possession.

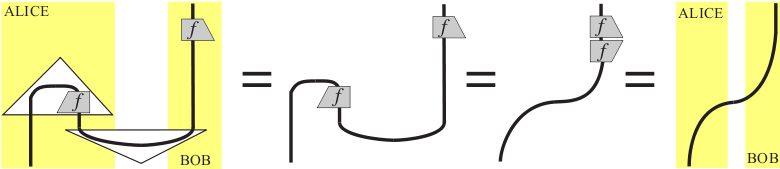

Alternative notations

There are a variety of different notations in use that describe the teleportation protocol. One common one is by using the notation of quantum gates. In the above derivation, the unitary transformation that is the change of basis (from the standard product basis into the Bell basis) can be written using quantum gates. Direct calculation shows that this gate is given by

where H is the one qubit Walsh-Hadamard gate and is the Controlled NOT gate.

Entanglement swapping

Teleportation can be applied not just to pure states, but also mixed states, that can be regarded as the state of a single subsystem of an entangled pair. The so-called entanglement swapping is a simple and illustrative example.

If Alice has a particle which is entangled with a particle owned by Bob, and Bob teleports it to Carol, then afterwards, Alice's particle is entangled with Carol's.

A more symmetric way to describe the situation is the following: Alice has one particle, Bob two, and Carol one. Alice's particle and Bob's first particle are entangled, and so are Bob's second and Carol's particle:

___

/ \

Alice-:-:-:-:-:-Bob1 -:- Bob2-:-:-:-:-:-Carol

\___/

Now, if Bob does a projective measurement on his two particles in the Bell state basis and communicates the results to Carol, as per the teleportation scheme described above, the state of Bob's first particle can be teleported to Carol's. Although Alice and Carol never interacted with each other, their particles are now entangled.

A detailed diagrammatic derivation of entanglement swapping has been given by Bob Coecke,[30] presented in terms of categorical quantum mechanics.

N-state particles

One can imagine how the teleportation scheme given above might be extended to N-state particles, i.e. particles whose states lie in the N dimensional Hilbert space. The combined system of the three particles now has an dimensional state space. To teleport, Alice makes a partial measurement on the two particles in her possession in some entangled basis on the dimensional subsystem. This measurement has equally probable outcomes, which are then communicated to Bob classically. Bob recovers the desired state by sending his particle through an appropriate unitary gate.

Logic gate teleportation

In general, mixed states ρ may be transported, and a linear transformation ω applied during teleportation, thus allowing data processing of quantum information. This is one of the foundational building blocks of quantum information processing. This is demonstrated below.

General description

A general teleportation scheme can be described as follows. Three quantum systems are involved. System 1 is the (unknown) state ρ to be teleported by Alice. Systems 2 and 3 are in a maximally entangled state ω that are distributed to Alice and Bob, respectively. The total system is then in the state

A successful teleportation process is a LOCC quantum channel Φ that satisfies

where Tr12 is the partial trace operation with respect systems 1 and 2, and denotes the composition of maps. This describes the channel in the Schrödinger picture.

Taking adjoint maps in the Heisenberg picture, the success condition becomes

for all observable O on Bob's system. The tensor factor in is while that of is .

Further details

The proposed channel Φ can be described more explicitly. To begin teleportation, Alice performs a local measurement on the two subsystems (1 and 2) in her possession. Assume the local measurement have effects

If the measurement registers the i-th outcome, the overall state collapses to

The tensor factor in is while that of is . Bob then applies a corresponding local operation Ψi on system 3. On the combined system, this is described by

where Id is the identity map on the composite system .

Therefore, the channel Φ is defined by

Notice Φ satisfies the definition of LOCC. As stated above, the teleportation is said to be successful if, for all observable O on Bob's system, the equality

holds. The left hand side of the equation is:

where Ψi* is the adjoint of Ψi in the Heisenberg picture. Assuming all objects are finite dimensional, this becomes

The success criterion for teleportation has the expression

Local explanation of the phenomenon

A local explanation of quantum teleportation is put forward by David Deutsch and Patrick Hayden, with respect to the many-worlds interpretation of Quantum mechanics. Their paper asserts that the two bits that Alice sends Bob contain "locally inaccessible information" resulting in the teleportation of the quantum state. "The ability of quantum information to flow through a classical channel ..., surviving decoherence, is ... the basis of quantum teleportation."[31]

See also

References

Specific

- 1 2 New York Times, Scientists Teleport Not Kirk, but an Atom (2004)

- 1 2 Barrett, M. D.; Chiaverini, J.; Schaetz, T.; Britton, J.; Itano, W. M.; Jost, J. D.; Knill, E.; Langer, C.; Leibfried, D.; Ozeri, R.; Wineland, D. J. (2004). "Deterministic quantum teleportation of atomic qubits". Nature. 429 (6993): 737–739. Bibcode:2004Natur.429..737B. doi:10.1038/nature02608.

- 1 2 Riebe, M.; Häffner, H.; Roos, C. F.; Hänsel, W.; Benhelm, J.; Lancaster, G. P. T.; Körber, T. W.; Becher, C.; Schmidt-Kaler, F.; James, D. F. V.; Blatt, R. (2004). "Deterministic quantum teleportation with atoms". Nature. 429 (6993): 734–737. Bibcode:2004Natur.429..734R. doi:10.1038/nature02570.

- ↑ C. H. Bennett, G. Brassard, C. Crépeau, R. Jozsa, A. Peres, W. K. Wootters, Teleporting an Unknown Quantum State via Dual Classical and Einstein–Podolsky–Rosen Channels, Phys. Rev. Lett. 70, 1895–1899 (1993) (online).

- ↑ A. Zeilinger, Dance of the Photons, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York, 2010, p. 46. ("The quantum mechanical solution [to teleportation] was proposed in 1993 by an international collaboration of six theoretical physicists: Charles Bennett of IBM; Gilles Brassard, Claude Crépeau, and Richard Jozsa of the University of Montreal; Asher Peres of the Technion (the Israel Institute of Technology in Haifa); and William K. Wooters of Williams College... The Bennett-Brassard-Crépeau-Jozsa-Peres-Wooters paper has the title 'Teleporting an Unknown Quantum State via Dual Classical and Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen channels.' To have the word 'teleporting' in the title of a physics paper was quite unusual at the time, since teleportation was considered to be part of science fiction and a somewhat shaky topic. But apparently, there was no better name for the interesting theoretical discovery these people made, and it was a very fitting name indeed.")

- ↑ Bouwmeester, D. et al. Experimental quantum teleportation. Nature 390, 575–579 (1997) http://www.nature.com/doifinder/10.1038/37539

- 1 2 Ma, X. S.; Herbst, T.; Scheidl, T.; Wang, D.; Kropatschek, S.; Naylor, W.; Wittmann, B.; Mech, A.; et al. (2012). "Quantum teleportation over 143 kilometres using active feed-forward". Nature. 489 (7415): 269–273. Bibcode:2012Natur.489..269M. doi:10.1038/nature11472. PMID 22951967.

- ↑ Hensen, B.; et al. (21 October 2015). "Loophole-free Bell inequality violation using electron spins separated by 1.3 kilometres". Nature. 526: 682–686. Bibcode:2015Natur.526..682H. doi:10.1038/nature15759. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- ↑ Markoff, Jack (21 October 2015). "Sorry, Einstein. Quantum Study Suggests 'Spooky Action' Is Real.". New York Times. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- ↑ Giustina, M.; et al. (16 December 2015). "Significant-Loophole-Free Test of Bell's Theorem with Entangled Photons". Physical Review Letters. 115: 250401. arXiv:1511.03190

. Bibcode:2015PhRvL.115y0401G. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.115.250401.

. Bibcode:2015PhRvL.115y0401G. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.115.250401. - ↑ Shalm, L. K.; et al. (16 December 2015). "Strong Loophole-Free Test of Local Realism". Physical Review Letters. 115: 250402. arXiv:1511.03189

. Bibcode:2015PhRvL.115y0402S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.115.250402.

. Bibcode:2015PhRvL.115y0402S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.115.250402. - ↑ D. Boschi; S. Branca; F. De Martini; L. Hardy; S. Popescu (1998). "Experimental Realization of Teleporting an Unknown Pure Quantum State via Dual Classical and Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen Channels". Physical Review Letters. 80 (6): 1121. arXiv:quant-ph/9710013

. Bibcode:1998PhRvL..80.1121B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.80.1121.

. Bibcode:1998PhRvL..80.1121B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.80.1121. - ↑ Rupert Ursin (August 2004). "Quantum teleportation across the Danube". Nature. Retrieved 2010-05-22.

- ↑ http://www.nature.com/nphoton/journal/v4/n6/full/nphoton.2010.87.html

- ↑ http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v489/n7415/full/nature11472.html

- ↑ Takesue, Hiroki; et al. (2015-10-20). "Quantum teleportation over 100 km of fiber using highly efficient superconducting nanowire single-photon detectors". Optica. 2 (10): 832–835. doi:10.1364/OPTICA.2.000832. Retrieved 2016-07-26.

- ↑ C. Nölleke, A. Neuzner, A. Reiserer, C. Hahn, G. Rempe, S. Ritter, Efficient Teleportation Between Remote Single-Atom Quantum Memories, Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 140403 (2013) (online, arXiv)

- ↑ Nature 430, 54-58 (1 July 2004) http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v430/n6995/full/nature02643.html

- ↑ Experimental quantum teleportation of a two-qubit composite system Qiang Zhang, Alexander Goebel, Claudia Wagenknecht, Yu-Ao Chen, Bo Zhao, Tao Yang, Alois Mair, Jörg Schmiedmayer & Jian-Wei Pan Nature Physics 2, 678–682

- ↑ Lee, Noriyuki; Hugo Benichi; Yuishi Takeno; Shuntaro Takeda; James Webb; Elanor Huntington; Akira Furusawa (April 2011). "Teleportation of Nonclassical Wave Packets of Light". Science. 332 (6027): 330–333. arXiv:1205.6253

. Bibcode:2011Sci...332..330L. doi:10.1126/science.1201034. Retrieved 2011-04-26.

. Bibcode:2011Sci...332..330L. doi:10.1126/science.1201034. Retrieved 2011-04-26. - ↑ Trute, Peter. "Quantum teleporter breakthrough". The University Of New South Wales. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- ↑ Takeda et al., "Deterministic quantum teleportation of photonic quantum bits by a hybrid technique", Nature, August 2013.

- ↑ Markoff, John (29 May 2014). "Scientists Report Finding Reliable Way to Teleport Data". New York Times. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

- ↑ Pfaff, W.; et al. (29 May 2014). "Unconditional quantum teleportation between distant solid-state quantum bits". Science. arXiv:1404.4369

. Bibcode:2014Sci...345..532P. doi:10.1126/science.1253512. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

. Bibcode:2014Sci...345..532P. doi:10.1126/science.1253512. Retrieved 29 May 2014. - ↑ Xi-Lin Wang, Xin-Dong Cai, Zu-En Su, Ming-Cheng Chen, Dian Wu, Li Li, Nai-Le Liu, Chao-Yang Lu & Jian-Wei Pan, Quantum teleportation of multiple degrees of freedom of a single photon, Nature 518, 516–519 (26 February 2015) http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v518/n7540/full/nature14246.html

- ↑ "Quantum teleportation between atomic systems over long distances". Phys.Org.

- ↑ http://www.nature.com/nphys/journal/vaop/ncurrent/full/nphys2631.html#auth-1

- ↑ Bob Coecke, "Quantum Picturalism", (2009) Contemporary Physics vol 51, pp59-83. (ArXiv 0908.1787)

- ↑ R. Penrose, Applications of negative dimensional tensors, In: Combinatorial Mathematics and its Applications, D.~Welsh (Ed), pages 221–244. Academic Press (1971).

- ↑ Bob Coecke, "The logic of entanglement". Research Report PRG-RR-03-12, 2003. arXiv:quant-ph/0402014 (8 page shortversion) (full 160 page version)

- ↑ Deutsch, David; Hayden, Patrick (1999). "Information Flow in Entangled Quantum Systems". Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 456 (1999): 1759–1774. arXiv:quant-ph/9906007

. Bibcode:2000RSPSA.456.1759H. doi:10.1098/rspa.2000.0585.

. Bibcode:2000RSPSA.456.1759H. doi:10.1098/rspa.2000.0585.

General

- Theoretical proposal:

- C. H. Bennett, G. Brassard, C. Crépeau, R. Jozsa, A. Peres, W. K. Wootters, Teleporting an Unknown Quantum State via Dual Classical and Einstein–Podolsky–Rosen Channels, Phys. Rev. Lett. 70, 1895–1899 (1993) (pdf). This is the seminal paper that laid out the entanglement protocol.

- Vaidman, L. (February 1994). "Teleportation of Quantum States". Phys. Rev. A. 49 (2): 1473–1476. arXiv:hep-th/9305062

. Bibcode:1994PhRvA..49.1473V. doi:10.1103/physreva.49.1473.

. Bibcode:1994PhRvA..49.1473V. doi:10.1103/physreva.49.1473. - Brassard, G; Braunstein, S; Cleve, R (1998). "Teleportation as a Quantum Computation". Physica D. 120 (1-2): 43–47. arXiv:quant-ph/9605035

. Bibcode:1998PhyD..120...43B. doi:10.1016/s0167-2789(98)00043-8.

. Bibcode:1998PhyD..120...43B. doi:10.1016/s0167-2789(98)00043-8. - A. Peres, "What is actually teleported?", IBM Journal of Research and Development Vol. 48, Issue 1, (2004)(this document online)

- G. Rigolin, Quantum Teleportation of an Arbitrary Two Qubit State and its Relation to Multipartite Entanglement, Phys. Rev. A 71 2005; 032303 (this document online)

- Shi-Biao Zheng (2004) "Scheme for approximate conditional teleportation of an unknown atomic state without the Bell-state measurement", Phys. Rev. A 69, 064302

- W. B. Cardoso, A. T. Avelar, B. Baseia, and N. G. de Almeida, "Teleportation of entangled states without Bell-state measurement", Phys. Rev. A 72, 045802 (2005).

- Michael N. Leuenberger, Michael E. Flatte, David D. Awschalom, "Teleportation of Electronic Many-Qubit States Encoded in the Electron Spin of Quantum Dots via Single Photons", Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 107401 (2005).

- A. N. Pyrkov, Tim Byrnes, "Quantum teleportation of spin coherent states: beyond continuous variables teleportation", New J. Phys. 16, 073038 (2014) (this document online)

- Yuchuan Wei, How to teleport a particle rather than a state, Phys Rev E93 (2016)066103.

- First experiments with photons:

- D. Bouwmeester, J.-W. Pan, K. Mattle, M. Eibl, H. Weinfurter, A. Zeilinger, Experimental Quantum Teleportation, Nature 390, 6660, 575-579 (1997).

- D. Boschi, S. Branca, F. De Martini, L. Hardy, & S. Popescu, Experimental Realization of Teleporting an Unknown Pure Quantum State via Dual classical and Einstein–Podolsky–Rosen channels, Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 6, 1121–1125 (1998)

- Kim, Y.-H.; Kulik, S.P.; Shih, Y. (2001). "Quantum teleportation of a polarization state with a complete bell state measurement". Phys. Rev. Lett. 86 (7): 1370. arXiv:quant-ph/0010046

. Bibcode:2001PhRvL..86.1370K. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.86.1370.

. Bibcode:2001PhRvL..86.1370K. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.86.1370. - Marcikic, I.; Tittel, W.; Zbinden, H.; Gisin, N. (2003). "Long-Distance Teleportation of Qubits at Telecommunication Wavelengths". Nature. 421 (6922): 509. arXiv:quant-ph/0301178

. Bibcode:2003Natur.421..509M. doi:10.1038/nature01376.

. Bibcode:2003Natur.421..509M. doi:10.1038/nature01376. - Ursin, R.; et al. (August 2004). "Communications: Quantum Teleportation Link across the Danube". Nature. 430 (7002): 849. Bibcode:2004Natur.430..849U. doi:10.1038/430849a.

- First experiments with atoms:

- Riebe, M.; Häffner, H.; Roos, C. F.; Hänsel, W.; Ruth, M.; Benhelm, J.; Lancaster, G. P. T.; Körber, T. W.; Becher, C.; Schmidt-Kaler, F.; James, D. F. V.; Blatt, R. (2004). "Deterministic Quantum Teleportation with Atoms". Nature. 429 (6993): 734–737. Bibcode:2004Natur.429..734R. doi:10.1038/nature02570.

- Barrett, M. D.; Chiaverini, J.; Schaetz, T.; Britton, J.; Itano, W. M.; Jost, J. D.; Knill, E.; Langer, C.; Leibfried, D.; Ozeri, R.; Wineland, D. J. (2004). "Deterministic Quantum Teleportation of Atomic Qubits". Nature. 429 (6993): 737. Bibcode:2004Natur.429..737B. doi:10.1038/nature02608.

- Olmschenk, S.; Matsukevich, D. N.; Maunz, P.; Hayes, D.; Duan, L.-M.; Monroe, C. (2009). "Quantum Teleportation between Distant Matter Qubits". Science. 323 (5913): 486. arXiv:0907.5240

. Bibcode:2009Sci...323..486O. doi:10.1126/science.1167209.

. Bibcode:2009Sci...323..486O. doi:10.1126/science.1167209.

External links

- Loophole-free Bell test - Kavli Institute of Nanoscience

- "Spooky action and beyond" - Interview with Prof. Dr. Anton Zeilinger about quantum teleportation. Date: 2006-02-16

- Quantum Teleportation at IBM

- Physicists Succeed In Transferring Information Between Matter And Light

- Quantum telecloning: Captain Kirk's clone and the eavesdropper

- Teleportation-based approaches to universal quantum computation

- Teleportation as a quantum computation

- Quantum teleportation with atoms: quantum process tomography

- Entangled State Teleportation

- Fidelity of quantum teleportation through noisy channels by

- TelePOVM— A generalized quantum teleportation scheme

- Entanglement Teleportation via Werner States

- Quantum Teleportation of a Polarization State

- The Time Travel Handbook: A Manual of Practical Teleportation & Time Travel

- letters to nature: Deterministic quantum teleportation with atoms

- Quantum teleportation with a complete Bell state measurement

- Welcome to the quantum Internet. Science News, Aug. 16 2008.

- Quantum experiments - interactive.

- A (mostly serious) introduction to quantum teleportation for non-physicists