QT interval

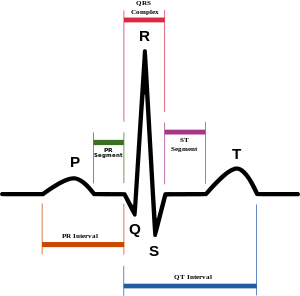

In cardiology, the QT interval is a measure of the time between the start of the Q wave and the end of the T wave in the heart's electrical cycle. The QT interval represents electrical depolarization and repolarization of the ventricles. A lengthened QT interval is a marker for the potential of ventricular tachyarrhythmias like torsades de pointes and a risk factor for sudden death.

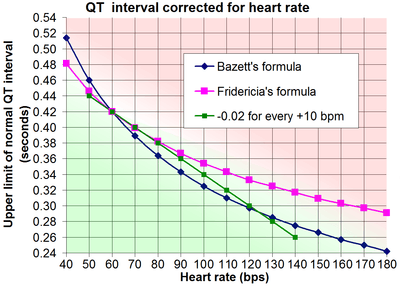

Correction for heart rate

Like the R-R interval, the QT interval is dependent on the heart rate in an obvious way (the faster the heart rate the shorter the R-R Interval and QT interval) and may be adjusted to improve the detection of patients at increased risk of ventricular arrhythmia. Modern computer-based ECG machines can easily calculate a corrected QT (QTc), but this correction may not aid in the detection of patients at increased risk of arrhythmia, as there are a number of different correction formulas.

The standard clinical correction is to use Bazett's formula,[1] named after physiologist Henry Cuthbert Bazett, calculating the heart rate-corrected QT interval (QTcB). Bazett's formula is based on observations of only 12 patients in 1920 and does not meet current scientific quality standards. A better[2] method may be the Framingham correction based on the Framingham Heart study, which used longterm cohort data of over 5,000 subjects.[3]

Bazett's formula is:

where QTcB is the QT interval corrected for heart rate, and RR is the interval from the onset of one QRS complex to the onset of the next QRS complex, measured in seconds, often derived from the heart rate (HR) as 60/HR (here QT is measured in milliseconds). However, this non-linear formula, obtained from data in only 39 young men, is not accurate, and over-corrects at high heart rates and under-corrects at low heart rates.[4]

Fridericia[5] has published an alternative correction formula using the cube-root of RR.

There are several other methods, such as regression-analysis:[3]

A recent retrospective study suggests that Fridericia's method and the Framingham method may produce results most useful for stratifying the 30-day and 1-year risks of mortality.[2]

Definitions of normal QTc vary from being equal to or less than 0.40 s (≤400 ms),[6] 0.41s (≤410ms),[7] 0.42s (≤420ms)[8] or 0.44s (≤440ms).[9] For risk of sudden cardiac death, "borderline QTc" in males is 431-450 ms, and in females 451-470 ms. An "abnormal" QTc in males is a QTc above 450 ms, and in females, above 470 ms.[10]

If there is not a very high or low heart rate, the upper limits of QT can roughly be estimated by taking QT=QTc at a heart rate of 60 beats per minute (bpm), and subtracting 0.02s from QT for every 10 bpm increase in heart rate. For example, taking normal QTc ≤ 0.42 s, QT would be expected to be 0.42 s or less at a heart rate of 60 bpm. For a heart rate of 70 bpm, QT would roughly be expected to be equal to or below 0.40 s. Likewise, for 80 bpm, QT would roughly be expected to be equal to or below 0.38 s.[6]

Measurement

The QT interval is most commonly measured in lead II for evaluation of serial ECGs, with leads I and V5 being comparable alternatives to lead II. Leads III, aVL and V1 are generally avoided for measurement of QT interval.[11] The accurate measurement of the QT interval is subjective[12] because the end of the T wave is not always clearly defined and usually merges gradually with the baseline. QT interval in an ECG complex can be measured manually by different methods such as the threshold method, in which the end of the T wave is determined by the point at which the component of the T wave merges with the isoelectric baseline or the tangent method, in which the end of the T wave is determined by the intersection of a tangent line extrapolated from the T wave at the point of maximum downslope to the isoelectric baseline.[13]

With the increased availability of digital ECGs with simultaneous 12-channel recording, QT measurement may also be done by the 'superimposed median beat' method. In the superimposed median beat method, a median ECG complex is constructed for each of the 12 leads. The 12 median beats are superimposed on each other and the QT interval is measured either from the earliest onset of the Q wave to the latest offset of the T wave or from the point of maximum convergence for the Q wave onset to the T wave offset.[14]

Abnormal intervals

Prolonged QTc causes premature action potentials during the late phases of depolarization. This increases the risk of developing ventricular arrhythmias or fatal ventricular fibrillations.[15] Higher rates of prolonged QTc are seen in females, older patients, high systolic blood pressure or heart rate, and short stature.[16] Prolonged QTc is also associated with EKG findings called Torsade de Pointes, which are known to degenerate into ventricular fibrillation, associated with higher mortality rates. There are many causes of prolonged QT intervals, acquired causes being more common than genetic.[17]

Genetic causes

An abnormally prolonged QT interval could be due to long QT syndrome, whereas an abnormally shortened QT interval could be due to short QT syndrome.

The QTc length is associated with variations in NOS1AP gene.[18] The autosomal recessive syndrome of Jervell and Lange-Nielsen is characterized by a prolonged QTc interval in conjunction with sensorineural hearing loss.

Due to adverse drug reactions

Prolongation of the QT interval may be due to an adverse drug reaction.[19] Many drugs such as haloperidol,[20] vemurafenib, ziprasidone, methadone[21] and sertindole[22] can prolong the QT interval. Some antiarrhythmic drugs, like amiodarone or sotalol work by getting a pharmacological QT prolongation. Also, some second-generation antihistamines, such as astemizole, have this effect. In addition, high blood alcohol concentrations prolongs the QT interval.[23] A possible interaction between selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and thiazide diuretics is associated with QT prolongation.[24] Macrolide antibiotics are also suspected to prolong the QT interval, after it was discovered recently that azithromycin was associated with an increase in cardiovascular death.[25]

Due to pathological conditions

Hypothyroidism, a condition of low function of the thyroid gland, can cause QT prolongation at the electrocardiogram. Acute hypocalcemia causes prolongation of the QT interval, which may lead to ventricular dysrhythmias.

A shortened QT can be associated with hypercalcemia.[26]

Use in drug approval studies

Since 2005, the FDA and European regulators have required that nearly all new molecular entities be evaluated in a Thorough QT (TQT) study to determine a drug's effect on the QT interval.[27] The TQT study serves to assess the potential arrhythmia liability of a drug. Traditionally, the QT interval has been evaluated by having individual human reader measure approximately nine cardiac beats per clinical timepoint. However, a number of recent drug approvals have used a highly automated approach, blending automated software algorithms with expert human readers reviewing a portion of the cardiac beats, to enable the assessment of significantly more beats per timepoint in order to improve precision and reduce cost.[28] As the pharmaceutical industry has gained experience in performing TQT studies, it has also become evident that traditional QT correction formulas such as QTcF, QTcB, and QTcLC may not always be suitable for evaluation of drugs impacting autonomic tone.[29] Current efforts are underway by industry and regulators to consider alternative methods to help evaluate QT liability in drugs affecting autonomic tone, such as QT beat-to-beat and Holter-bin methodologies.[30]

As a predictor of mortality

Electrocardiography is a safe and noninvasive tool that can be used to identify those with a higher risk of mortality. In the general population, there has been no consistent evidence that prolonged QTc interval in isolation is associated with an increase in mortality from cardiovascular disease.[31] However, several studies have examined prolonged QT interval as a predictor of mortality for diseased subsets of the population.

Rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis is the most common inflammatory arthritis.[32] Studies have linked rheumatoid arthritis with increased death from cardiovascular disease.[32] In a 2014 study,[15] Panoulas et al. found a 50 ms increase in QTc interval increased the odds of all-cause mortality by 2.17 in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Patients with the highest QTc interval (> 424 ms) had higher mortality than those with a lower QTc interval. The association was lost when calculations were adjusted for C-reactive protein levels. The researchers proposed that inflammation prolonged the QTc interval and created arrhythmias that were associated with higher mortality rates. However, the mechanism by which C-reactive protein is associated with the QTc interval is still not understood.

Type 1 diabetes

Compared to the general population, type 1 diabetes may increase the risk of mortality, due largely to an increased risk of cardiovascular disease.[16][33] Almost half of patients with type 1 diabetes have a prolonged QTc interval (> 440 ms).[16] Diabetes with a prolonged QTc interval was associated with a 29% mortality over 10 years in comparison to 19% with a normal QTc interval.[16] Anti-hypertensive drugs increased the QTc interval, but were not an independent predictor of mortality.[16]

Type 2 diabetes

QT interval dispersion (QTd) is the maximum QT interval minus the minimum QT interval, and is linked with ventricular repolarization.[34] A QTd over 80 ms is considered abnormally prolonged.[35] Increased QTd is associated with mortality in type 2 diabetes.[35] QTd is a better predictor of cardiovascular death than QTc, which was unassocited with mortality in type 2 diabetes.[35] QTd higher than 80 ms had a relative risk of 1.26 of dying from cardiovascular disease compared to a normal QTd.

See also

References

- 1 2 Bazett HC. (1920). "An analysis of the time-relations of electrocardiograms". Heart (7): 353–370.

- 1 2 Bert Vandenberk, Eline Vandael, Tomas Robyns, Joris Vandenberghe, Christophe Garweg, Veerle Foulon, Joris Ector and Rik Willems (2016-06-17), "Which QT Correction Formulae to Use for QT Monitoring?", Journal of the American Heart Association

- 1 2 Sagie A, Larson MG, Goldberg RJ, Bengston JR, Levy D (1992). "An improved method for adjusting the QT interval for heart rate (the Framingham Heart Study)". Am J Cardiol. 70 (7): 797–801. doi:10.1016/0002-9149(92)90562-D. PMID 1519533.

- ↑ Salvi V, Karnad DR, Panicker GK, Kothari S (2010). "Update on the evaluation of a new drug for effects on cardiac repolarization in humans: issues in early drug development". Br J Pharmacol. 159 (1): 34–48. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00427.x. PMC 2823350

. PMID 19775279.

. PMID 19775279. - 1 2 Fridericia LS (1920). "The duration of systole in the electrocardiogram of normal subjects and of patients with heart disease". Acta Medica Scandinavica (53): 469–486.

- 1 2 3 Lesson III. Characteristics of the Normal ECG Frank G. Yanowitz, MD. Professor of Medicine. University of Utah School of Medicine. Retrieved on Mars 23, 2010

- ↑ Loyola University Chicago Stritch School of Medicine > Medicine I By Matthew Fitz, M.D. Retrieved on Mars 23, 2010

- ↑ ecglibrary.com > A normal adult 12-lead ECG Retrieved on Mars 23, 2010

- ↑ Image for Cardiovascular Physiology Concepts > Electrocardiogram (EKG, ECG) By Richard E Klabunde PhD

- ↑ medscape.com > QTc Prolongation and Risk of Sudden Cardiac Death: Is the Debate Over? February 3, 2006

- ↑ Panicker GK, Salvi V, Karnad DR, Chakraborty S, Manohar D, Lokhandwala Y, Kothari S (2014). "Drug-induced QT prolongation when QT interval is measured in each of the 12 ECG leads in men and women in a thorough QT study.". J Electrocardiol. 47 (47(2)): 155–157. doi:10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2013.11.004. PMID 24388488.

- ↑ Panicker GK, Karnad DR, Joshi R, Shetty S, Vyas N, Kothari S, Narula D (2009). "Z-score for benchmarking reader competence in a central ECG laboratory". Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 14 (14(1)): 19–25. doi:10.1111/j.1542-474X.2008.00269.x. PMID 19149789.

- ↑ Panicker GK, Karnad DR, Natekar M, Kothari S, Narula D, Lokhandwala Y (2009). "Intra- and interreader variability in QT interval measurement by tangent and threshold methods in a central electrocardiogram laboratory". J Electrocardiol. 42 (42(4)): 348–52. doi:10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2009.01.003. PMID 19261293.

- ↑ Salvi V, Karnad DR, Panicker GK, Natekar M, Hingorani P, Kerkar V, Ramasamy A, de Vries M, Zumbrunnen T, Kothari S, Narula D (2011). "Comparison of 5 methods of QT interval measurements on electrocardiograms from a thorough QT/QTc study: effect on assay sensitivity and categorical outliers". J Electrocardiol. 44 (44(2)): 96–104. doi:10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2010.11.010. PMID 21238976.

- 1 2 Panoulas VF, Toms TE, Douglas KM, et al. (January 2014). "Prolonged QTc interval predicts all-cause mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: an association driven by high inflammatory burden". Rheumatology. 53 (1): 131–7. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/ket338. PMID 24097136.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Rossing P, Breum L, Major-Pedersen A, et al. (March 2001). "Prolonged QTc interval predicts mortality in patients with Type 1 diabetes mellitus". Diabetic Medicine. 18 (3): 199–205. doi:10.1046/j.1464-5491.2001.00446.x. PMID 11318840.

- ↑ Van Noord, C; Eijgelsheim, M; Stricker, BHC (2010). "Drug- and non-drug-associated QT interval prolongation.". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 70 (1): 16–23. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2010.03660.x. PMID 20642543.

- ↑ Arking DE, Pfeufer A, Post W, et al. (June 2006). "A common genetic variant in the NOS1 regulator NOS1AP modulates cardiac repolarization". Nature Genetics. 38 (6): 644–51. doi:10.1038/ng1790. PMID 16648850.

- ↑ Leitch A, McGinness P, Wallbridge D (September 2007). "Calculate the QT interval in patients taking drugs for dementia". BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 335 (7619): 557. doi:10.1136/bmj.39020.710602.47. PMC 1976518

. PMID 17855324.

. PMID 17855324. - ↑ "Information for Healthcare Professionals: Haloperidol (marketed as Haldol, Haldol Decanoate and Haldol Lactate)". Archived from the original on 2007-10-11. Retrieved 2007-09-18.

- ↑ Haigney, Mark. "Cardiotoxicity of methadone" (PDF). Director of Cardiology. Retrieved 21 February 2013.

- ↑ Lewis R, Bagnall AM, Leitner M (2005). "Sertindole for schizophrenia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD001715. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001715.pub2. PMID 16034864.

- ↑ Aasebø W, Erikssen J, Jonsbu J, Stavem K (April 2007). "ECG changes in patients with acute ethanol intoxication". Scandinavian Cardiovascular Journal. 41 (2): 79–84. doi:10.1080/14017430601091698. PMID 17454831.

- ↑ Tatonetti NP, Ye PP, Daneshjou R, Altman RB (March 2012). "Data-driven prediction of drug effects and interactions". Science Translational Medicine. 4 (125): 125ra31. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3003377. PMC 3382018

. PMID 22422992.

. PMID 22422992. - ↑ http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/Drugsafety/ucm304372.htm[]

- ↑ Hypercalcemia

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 6, 2010. Retrieved December 9, 2009.

- ↑ iCardiac Applies Automated Approach to Thorough QT Study for a Leading Pharmaceutical Company - Applied Clinical Trials

- ↑ "Garnett" (PDF). Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- ↑ http://thew-project.org/document/FDA%20CPI%20project.pdf[]

- ↑ Montanez A, Ruskin JN, Hebert PR, Lamas GA, Hennekens CH (May 2004). "Prolonged QTc interval and risks of total and cardiovascular mortality and sudden death in the general population: a review and qualitative overview of the prospective cohort studies". Archives of Internal Medicine. 164 (9): 943–8. doi:10.1001/archinte.164.9.943. PMID 15136301.

- 1 2 Solomon DH, Karlson EW, Rimm EB, et al. (March 2003). "Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in women diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis". Circulation. 107 (9): 1303–7. doi:10.1161/01.cir.0000054612.26458.b2. PMID 12628952.

- ↑ Borch-Johnsen K, Andersen PK, Deckert T (August 1985). "The effect of proteinuria on relative mortality in type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus". Diabetologia. 28 (8): 590–6. doi:10.1007/bf00281993. PMID 4054448.

- ↑ Okin PM, Devereux RB, Howard BV, Fabsitz RR, Lee ET, Welty TK (2000). "Assessment of QT interval and QT dispersion for prediction of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in American Indians: The Strong Heart Study". Circulation. 101 (1): 61–6. doi:10.1161/01.cir.101.1.61. PMID 10618305.

- 1 2 3 Giunti S, Gruden G, Fornengo P, et al. (March 2012). "Increased QT interval dispersion predicts 15-year cardiovascular mortality in type 2 diabetic subjects: the population-based Casale Monferrato Study". Diabetes Care. 35 (3): 581–3. doi:10.2337/dc11-1397. PMC 3322722

. PMID 22301117.

. PMID 22301117.