Penang

| Penang | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| State | |||

| Other transcription(s) | |||

| • Malay | Pulau Pinang | ||

| • Chinese | 槟城 | ||

| • Tamil | பினாங்கு | ||

|

| |||

| |||

| Nickname(s): Pearl of the Orient | |||

|

Motto: Bersatu dan Setia (Malay) United and Loyal Let Penang Lead (unofficial)[1] | |||

| Anthem: Untuk Negeri Kita ("For Our State") | |||

|

| |||

| Coordinates: 5°24′N 100°14′E / 5.400°N 100.233°ECoordinates: 5°24′N 100°14′E / 5.400°N 100.233°E | |||

| Capital | George Town | ||

| Government | |||

| • Yang di-Pertua Negeri | Abdul Rahman Abbas | ||

| • Chief Minister | Lim Guan Eng (DAP) | ||

| Area[2] | |||

| • Total | 1,031 km2 (398 sq mi) | ||

| Population (2016)[3] | |||

| • Total | 1,889,835 | ||

| • Density | 1,800/km2 (4,700/sq mi) | ||

| Demonym(s) | Penangite | ||

| Human Development Index | |||

| • HDI (2010) | 0.773 (high) (3rd) | ||

| Time zone | MST (UTC+8) | ||

| • Summer (DST) | Not observed (UTC) | ||

| Postal code | 10xxx–14xxx | ||

| Calling code | +604 | ||

| Vehicle registration | P | ||

| Ceded by Kedah to the British East India Company | 11 August 1786 | ||

| Made a British crown colony as part of the Straits Settlements | 1 April 1867 | ||

| Japanese occupation | 19 December 1941 | ||

| Accession into the Federation of Malaya | 31 January 1948 | ||

| Independence as part of the Federation of Malaya | 31 August 1957 | ||

| Website |

penang | ||

| ^[a] 2,491 people per km2 on Penang Island and 1,049 people per km2 in Seberang Perai | |||

Penang is a Malaysian state located on the northwest coast of Peninsular Malaysia, by the Strait of Malacca. It comprises two parts – Penang Island, where the capital city, George Town, is located, and Seberang Perai (formerly Province Wellesley) on the Malay Peninsula. Penang is bordered by Kedah to the north and east, and Perak to the south.

Known as the Silicon Valley of the East due to its industries, Penang is also one of the most urbanised and economically important states in the country.[4][5][6][7] George Town, which was founded by the British in 1786, is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and a thriving tourist destination. Penang has the third-highest Human Development Index in Malaysia, after the state of Selangor and the federal territory of Kuala Lumpur.

Its heterogeneous population is highly diverse in ethnicity, culture, language and religion. A resident of Penang is colloquially known as a Penangite (in English), Penang Lang (in Penang Hokkien) or Penangkaran (in Tamil).

Etymology

The name of "Penang" comes from the modern Malay name Pulau Pinang, which means "island of the areca nut palm" (Areca catechu, family Palmae).[8] The name Penang may refer either to Penang Island (Pulau Pinang) or the state of Penang (Negeri Pulau Pinang). The word is derived from the Chinese name for the areca nut or betel palm.

Penang is also known as "The Pearl of the Orient", "东方之珠" and Pulau Pinang Pulau Mutiara (Penang, The Island of Pearls). Penang is shortened as "PG" in English, or "PP" in Malay.[9]

In Malay, George Town was labelled in old maps as Tanjung Penaga (Cape Penaigre),[10] named after the many ballnut trees (Alexandrian laurels, Calophyllum inophyllum) on the coast, but now usually shortened as Tanjung (the Cape).[11][12]

Early Malays called it Pulau Ka-Satu or "First (or Single) Island" because it was the largest island encountered on the trading sea-route between Lingga and Kedah.[13] The Siamese, then the overlord of the Kedah Sultanate, referred to the island as Koh Maak. (Thai: เกาะหมาก "Areca nut palm Island")[14][15] In the 15th century, the island of Penang was referred to as Bīnláng Yù (simplified Chinese: 槟榔屿; traditional Chinese: 檳榔嶼) in the navigational drawings used by Admiral Zheng He of Ming-dynasty China in his expeditions to the South Seas.[14][16] The 16th-century Portuguese historian Emanuel Godinho de Eredia's map of the Malay Peninsula in his "Description of Malaca" in 1613 referred to the island as Pulo Pinaom.[10]

History

Prehistory

Archaeological evidence shows that Penang was inhabited by the Semang-Pangan of the Juru and Yen lineage. Both of these are now considered extinct cultures. They were hunter-gatherers of the Negrito stock having short stature and dark complexion, and were dispersed by the Malays as far back as 900 years ago. The last recorded aboriginal settlement in Penang was in the 1920s in Kubang Semang.[17] The first evidence of prehistoric human settlement in what is now Penang were found in Guar Kepah, a cave in Seberang Perai in 1860. Based on mounds of sea shells with human skeletons, stone implements, broken ceramics, and food leftovers inside, the settlement was estimated to be between 3000 and 4000 years old. Other stone tools found in various places on the island of Penang pointed to the existence of Neolithic settlements dating to 5000 years ago.[18]

Early history

The earliest use of the geographical term "Penang Island" may have been the "The Nautical Charts of Zheng He" dated to the expeditions of Zheng He (Cheng Ho) in Ming dynasty during the reign of the Yongle Emperor. In the 15th century, the Chinese navy using the record of nautical chart as navigation guide from "Con Dao Islands" (Pulo Condore) to Penang Island, Penang has been seen to trade with the Ming dynasty in the 15th century.

One of the first Englishmen to reach Penang was the navigator and privateer Sir James Lancaster who on 10 April 1591, commanding the Edward Bonadventure, set sail from Plymouth for the East Indies, reaching Penang in June 1592, remaining on the island until September of the same year and pillaging every vessel he encountered, only to return to England in May 1594.[19]

Founding of Penang

In the early 18th century, the Minangkabaus of Sumatra were Datuk Jannaton, Nakhoda Bayan, Nakhoda Intan and Nakhoda Kecil opened up a settlement at Penang island.[20] Haji Muhammad Salleh, known as Nakhoda Intan, anchored in Batu Uban and built Masjid Jamek for his seaside settlement in 1734.[21] Later the Arabs arrived in Penang and settled mainly in Jelutong. The Arabs then intermarried with the Minangkabau and this gave rise to Arab-Minangkabau admixture who are described as Malay as they have assimilated into the local Malay community. The Arabs were among the wealthiest in Penang. The richest and prominent Arab was Sayyid Husain Aidid.[22]

On 17 July 1786, Captain Francis Light, an English trader-adventurer working for the Madras-based firm, Jourdain Sullivan, de Souza and the East India Company, landed on the island at what was later called Fort Cornwallis, took formal possession of the island "in the name of His Britannic Majesty, King George III and the Honourable East India Company" and founded a settlement at the northeast point of the island. On 12 August 1786, Light renamed the island the Prince of Wales Island in honour of the heir to the British throne, and named the new settlement George Town in honour of King George III.

Sultan Abdullah Mukarram Shah of Kedah leased the island to him in exchange for military protection from Siamese and Burmese armies who were threatening Kedah. For Light, Penang was a "convenient magazine for trade" and an ideal location to curtail French expansion in Indochina and to check the Dutch foothold in Sumatra.[23] Penang was Britain's first settlement in Southeast Asia, and was one of the first establishments of the second British Empire after the loss of its North American colonies.[24][25] In Malaysian history, the occasion marked the beginning of more than a century of British involvement in Malaya.

Unfortunately for the Sultan, the EIC's new governor-general Charles Cornwallis made it clear that he could not be party to the Sultan's disputes with the other Malay princes, or promise to protect him from the Siamese or Burmese .[26] Unbeknownst to Sultan Abdullah, Light had decided to conceal the facts of the agreement from both parties. When Light reneged on his promise of protection, the Sultan tried unsuccessfully to recapture Prince of Wales Island in 1790, and the Sultan was forced to cede the island to the company for an honorarium of 6,000 Spanish dollars per annum. Light established Penang as a free port to entice traders away from nearby Dutch trading posts. Trade in Penang grew exponentially soon after its founding – incoming ships and boats to Penang increased from 85 in 1786 to 3569 in 1802.[27]

He also encouraged immigrants by promising them as much land as they could clear and by reportedly firing silver dollars from his ship's cannons deep into the jungle. Many early settlers, including Light himself in 1794, succumbed to malaria, earning early Penang the epithet "the white man's grave".[28][29]

Colonial Penang

After Light's demise, Lieutenant-Colonel Arthur Wellesley, later to be Duke of Wellington, arrived in Penang to co-ordinate the defences of the island. In 1800, Lieutenant-Governor Sir George Leith secured a strip of land across the channel as a buffer against attacks and named it Province Wellesley (today Seberang Perai). The annual payment to Sultan of Kedah was increased to 10,000 Spanish dollars per annum after the acquisition. Today, as a symbolic gesture, the Penang state government still pays Kedah RM 10,000.00 annually.[30]

In 1796 Penang was made a penal settlement when 700 convicts were transferred from the Andaman Islands.[31] In 1805 Penang was made a separate presidency (ranking with Bombay and Madras); and when in 1826 Singapore and Malacca were incorporated with it, Penang continued to be the seat of government of the Straits Settlements, an extension of the British Raj. In 1829 Penang was reduced from the rank of a presidency, and eight years later, the fast-booming town of Singapore was made the capital of the Straits Settlements. In 1867 the Straits Settlements were created a Crown colony under direct British rule, in which Penang was included.[32]

Colonial Penang thrived from trade in pepper and spices, Indian piece goods, betel nut, tin, opium, and rice. The Bengal Presidency was aware of Penang's potential as an alternative to Dutch Moluccas as a source of spice production. Development of export crops became the chief means of covering administrative costs in Penang. The development of the spice economy drove the movement of Chinese settlers to the island, which was actively encouraged by the British.

However, Penang port's initial pre-eminence was later supplanted by Singapore owing to the latter's superior geographical location. In spite of this, Penang remained an important feeder to Singapore – funnelling the exports meant for global shipping lines by ocean-going ships which had bypassed other regional ports. The replacement of sailing vessels by steamships in the mid-19th century cemented Penang's secondary importance after Singapore. Penang's most important trading partners were China, India, Siam, the Dutch East Indies and Britain, as well as fellow Straits Settlements, Singapore and Malacca.[33]

The rapid population growth stemming from economic development created problems such as sanitation, inadequate urban infrastructure, transportation and public health. Main roads were extended from the capital into the fertile cultivated spice farms further inland. But to sate the severe labour shortages in public works, the government began the practice of employing Indian convict workers as low-cost labourers. A great number of them worked on Penang' streets, draining swamps and clearing forests, constructing drainage ditches, and laying pipeworks for clean water.[33] Indeed, convict labour was key to Penang's successful colonisation as many found employment in the civil service, military, and even as private servants to the colonial officials and private individuals.[33]

For ten days in August 1867, Penang was gripped with civil unrest during what was known as the Penang Riot which pitted rival secret societies Kean Teik Tong (the Tua Pek Kong Hoey), led by Khoo Thean Teik and the Red Flag against the alliance of the Ghee Hin Kongsi and the White Flag, which the British under newly appointed lieutenant-governor Col. Edward Anson put down with sepoy reinforcement after days of chaos.[34]

At the turn of the century, Penang, with her large population of Chinese immigrants, was a natural place for the Chinese nationalist Sun Yat-sen to raise funds for his revolutionary efforts in Qing China. These frequent visits culminated in the famous 1910 Penang conference which paved the way to the ultimately triumphant Wuchang uprising which overthrew the Manchu government.[35]

World wars

| Incorporated into | Date |

|---|---|

| Straits Settlements | 1826 |

| Crown Colony | 1867 |

| Japanese occupation | 19 December 1941 |

| Malayan Union | 1 April 1946 |

| Federation of Malaya | 31 January 1948 |

| Independence of the Federation of Malaya | 31 August 1957 |

| Malaysia | 16 September 1963 |

During World War I, in the Battle of Penang, the German cruiser SMS Emden surreptitiously sailed to Penang and sank two Allied warships off its coast – the Russian cruiser Zhemchug in the North Channel, and as it was leaving the island, the French torpedo boat, Mosquet 10 miles off Muka Head.[36][37]

In the interwar years and during the Great Depression, the Penang business elites suffered numerous setbacks but also witnessed the rise of the nouveau-riche such as the legendary Lim Lean Teng. Rice-milling, opium syndicates, and pawnbroking were among the most lucrative businesses. In 1922, the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VIII) visited Penang amid much splendour.[38]

During World War II, Penang, then a British garrison, suffered devastating aerial bombardments and finally fell to invading Japanese forces on 19 December 1941 as the British withdrew to Singapore after declaring George Town an open city.[39]

Penang under Japanese occupation was marked by widespread fear, hunger, and the Sook Ching massacres which targeted the local Chinese populace.[39][40] Especially feared was the Japanese military police Kempeitai and its network of informants. Penang was administered by four successive Japanese governors, beginning with Lt-Gen Shotaro Katayama.[41] Penang also served as a U-boat base for the Monsun boats in the Indian Ocean for Japan's ally, Germany during the War.[42]

Between 1944 and 1945, the Allies launched bombing raids throughout Southeast Asia, including Penang. The destruction of the Penang Secretariat building by Allied bombing in the final months of the Occupation caused the loss of the greater part of the British and Japanese records concerning the island, causing enormous difficulties to compile a comprehensive history of Penang.[43]

Following Japanese surrender in the War, on 21 August 1945 the Penang Shimbun published the statement of capitulation issued by the Emperor. The official British party reached Penang on 1 September, and after a meeting between the British Commander-in-Chief of the East Indies Fleet and Japanese Rear-Admiral Uzumi on 2 September, a detachment of the Royal Marines landed and occupied the island on 3 September. A formal ceremony to signify British repossession of Penang took place at Swettenham Pier on 5 September 1945.[43]

Independence and after

The British returned at the end of the war and were intent on consolidating rule over their possessions in British Malaya into a single administrative entity called the Malayan Union, but by then British prestige and an image of invincibility were severely dented. The Malayan Union was vehemently rejected by the people, and the Federation of Malaya was formed in its place in 1948, uniting the then Federated Malay States, Unfederated Malay States, and the Straits Settlements (excluding Singapore) of which Penang was a part. Independence seemed an inevitable conclusion.

Nonetheless, the idea of the absorption of the British colony of Penang into the vast Malay heartland alarmed some quarters of the population. The Penang Secessionist Movement (active from 1948 to 1951) was formed to preclude Penang's merger with Malaya, but was unsuccessful due to British disapproval. Another attempt by the secessionists to join Penang with Singapore as a Crown Colony was also unfruitful.[44] The movement was spearheaded by, among others, the Penang Chinese Chamber of Commerce, the Penang Indian Chamber of Commerce, and the Penang Clerical and Administrative Staff Union.[45]

Penang, with the rest of the Federation of Malaya gained independence in 1957, and subsequently became a member state of Malaysia in 1963.[24] Wong Pow Nee of the Malaysian Chinese Association (MCA) party was Penang's first Chief Minister.[46] He presided during the period of the Communist insurgency and the formation of Malaysia.[47]

The island was, since colonial times, a free port until its sudden revocation by the federal government in 1969.[48] Despite this abrupt setback, from the 1970s to the late 1990s the state under the administration of Chief Minister Lim Chong Eu built up one of the largest electronics manufacturing bases in Asia, the Free Trade Zone in Bayan Lepas located at the southeastern part of Penang Island.[49]

The pre-War houses in the historic centre of George Town was for half a century until January 2001 protected from urban development due to the Rent Control Act which prohibited landlords from arbitrarily raising rentals as a measure to provide affordable housing to the low-income population.[50] Its eventual repeal visibly changed the landscape of Penang's demographic pattern and economic activity: it led to overnight appreciation of house and real estate prices, forcing out tenants of multiple generations out of their homes to the city outskirts and the development of new townships and hitherto sparsely populated areas of Penang; the demolition of many pre-War houses and the mushrooming of high-rise residences and office buildings; and the emptying out and dilapidation of many areas in the city centre. Unperturbed development sparked concerns of the continued existence of heritage buildings and Penang's collection of pre-War houses (southeast Asia's largest), leading to more vigorous conservation efforts. This was paid handsomely when on 7 July 2008, George Town wa s inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, alongside Malacca. It is recognised as having "a unique architectural and cultural townscape without parallel anywhere in East and Southeast Asia".[51]

The Indian Ocean tsunami which struck on Boxing Day of 2004 hit the western and northern coasts of Penang Island, claiming 52 lives (out of 68 in Malaysia).[52]

Whilst George Town had been declared a city by Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II in 1957,[53] Penang island as a whole was awarded city status by the Malaysian government in 2015.[54]

Geography

Topography

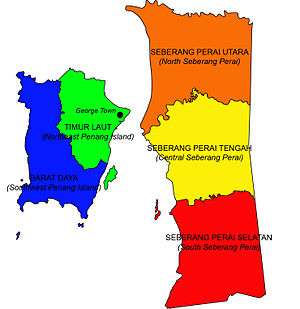

Penang is a geographically divided into two sections:

- Penang Island (Pulau Pinang in Malay): an island of 293 km2 (113 sq mi) located in the Straits of Malacca;

- Seberang Perai: a narrow hinterland of 653 km2 (252 sq mi) on the peninsula across a narrow channel whose smallest width is 4 km (2.5 mi). It is bordered by Kedah in the east and north (demarcated by the Muda River), and by Perak in the south.

The body of water between Penang Island and Seberang Perai consists of the North Channel to the north of George Town and the South Channel to the south of it. Penang Island is irregularly shaped, with a granitic, hilly and mostly forested interior. The coastal plains are narrow, the most extensive of which is in the northeast. In general, the island can be distinguished into five areas:

- The northeastern plains form a triangular promontory where the state capital is situated. This densely populated inner city is the administrative, commercial, and cultural centre of Penang.

- The southeast, once consisting of rice fields and mangroves, has been completely transformed into new townships and industrial areas.

- The northwest consists of a coastal fringe of sandy beaches lined with resort hotels and residences.

- The southwest contains the only large pockets of scenic countryside with fishing villages, fruit orchards, and mangroves.

- The central hill range, with the highest point being Western Hill (part of Penang Hill) at 830 metres above sea level, is an important forested catchment area.[55]

The topography of Seberang Perai, comprising more than half of the land area of Penang, is mostly flat save for Bukit Mertajam, the name of the hillock and the eponymous town at its foot.[56] It has a long coastline, the majority of which is lined with mangrove. Butterworth, the main town in Seberang Perai, lies along the Perai River estuary and faces George Town at a distance of 3 km (1.9 mi) across the channel to the east.

The island of Penang is composed of two districts:

Seberang Perai is subdivided into three districts:

- North Seberang Perai District

- Central Seberang Perai District

- South Seberang Perai District

Due to the lack of land for development in Penang, a few land reclamation projects had been undertaken to provide suitable low-lying land in high-demand areas such as Tanjung Tokong, Jelutong (construction of Jelutong Expressway) and Queensbay. These projects had been implicated in the change of tidal flow along coastal areas of Penang Island and were postulated to have caused the silting of Gurney Drive after the Tanjung Tokong reclamation.[57]

Geology

There are three main geological formations in Penang, i.e. the orthoclase to intermediate microcline granite, microcline granite, and the Mahang formation (mainly ferruginous spotted slate). Penang Island has no sedimentary rocks[58] and most of the island is underlain by igneous rocks which are granites in the IUGS or Streckeisen classification. On the basis of proportions of alkali feldspar to total feldspar, granites on Penang island are further distinguished into two main groups: the North Penang Pluton (approximately north of latitude 5° 23'), and the South Penang Pluton. The former group is subdivided into the Ferringhi Granite, the Tanjung Bungah Granite and the Muka Head Microgranite, whereas the latter is subdivided into the Batu Maung Granite and the Sungai Ara Granite. A study of three disparate locations on the island show that the soil profile in Batu Ferringhi (of early Jurassic age) is silty whereas those in Paya Terubong (early Permian – late Carboniferous) and Tanjung Bungah (early Jurassic) are clayey.[59]

Drainage system

The major rivers in Penang include the Pinang River, Air Itam River, Gelugor River, Dondang River, Teluk Bahang River, Tukun River, Betung River, and Prai River. The Muda River separates Penang from Kedah in the north, while the Kerian River forms the boundary between Penang, Kedah, and Perak. The latter is known for its firefly colonies.[60]

Climate

| Penang | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Like the rest of Malaysia, Penang has a tropical climate, specifically a tropical rainforest climate bordering on a tropical monsoon climate, though Penang does experience slightly drier conditions from December to February of the following year. The climate is very much dictated by the surrounding sea and the wind system. Penang's proximity with Sumatra, Indonesia makes it susceptible to dust particles carried by wind from perennial but transient forest fires, creating a phenomenon known as the haze.[61]

The Bayan Lepas Regional Meteorological Office is the primary weather forecast facility for northern Peninsular Malaysia.[62]

| Temperature (day) | 30–32 °C |

| Temperature (night) | 23–25 °C |

| Ave annual rainfall | 2670 mm |

| Relative humidity | 0%–50% |

| Climate data for Penang | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 31.6 (88.9) |

32.2 (90) |

32.2 (90) |

31.9 (89.4) |

31.6 (88.9) |

31.4 (88.5) |

31.0 (87.8) |

30.9 (87.6) |

30.4 (86.7) |

30.4 (86.7) |

30.7 (87.3) |

31.1 (88) |

31.3 (88.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 26.9 (80.4) |

27.4 (81.3) |

27.6 (81.7) |

27.7 (81.9) |

27.6 (81.7) |

27.3 (81.1) |

26.9 (80.4) |

26.8 (80.2) |

26.5 (79.7) |

26.4 (79.5) |

26.5 (79.7) |

26.7 (80.1) |

27.0 (80.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 23.2 (73.8) |

23.5 (74.3) |

23.7 (74.7) |

24.1 (75.4) |

24.2 (75.6) |

23.8 (74.8) |

23.4 (74.1) |

23.4 (74.1) |

23.2 (73.8) |

23.3 (73.9) |

23.3 (73.9) |

23.4 (74.1) |

23.5 (74.4) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 68.7 (2.705) |

71.7 (2.823) |

146.4 (5.764) |

220.5 (8.681) |

203.4 (8.008) |

178.0 (7.008) |

192.1 (7.563) |

242.4 (9.543) |

356.1 (14.02) |

383.0 (15.079) |

231.8 (9.126) |

113.5 (4.469) |

2,407.6 (94.787) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 5 | 6 | 9 | 14 | 14 | 11 | 12 | 14 | 18 | 19 | 15 | 9 | 146 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 248.8 | 233.2 | 235.3 | 224.5 | 203.6 | 202.4 | 205.5 | 188.8 | 161.0 | 170.2 | 182.1 | 209.0 | 2,464.4 |

| Source: NOAA[63] | |||||||||||||

Suburbs and neighbourhoods

Penang Island

Air Itam – Bagan Jermal – Balik Pulau – Bandar Baru Air Itam – Batu Ferringhi – Batu Maung – Batu Lanchang – Bayan Baru – Bayan Lepas – Gelugor – Gertak Sanggul – Green Lane – Gurney Drive – Tanjung Tokong – Jelutong – Mount Erskine – Pantai Acheh – Paya Terubong – Pulau Tikus – Pulau Betong – Relau – Sungai Ara – Sungai Dua – Sungai Nibong – Sungai Pinang – Tanjung Bungah – Tanjung Tokong – Teluk Bahang – Teluk Kumbar

Seberang Perai

Alma – Bagan Ajam – Bagan Luar – Batu Kawan – Bukit Mertajam – Bukit Minyak – Bukit Tambun – Butterworth – Ceruk Tok Kun – Jawi – Juru – Kepala Batas – Mak Mandin – Nibong Tebal – Permatang Pauh – Perai – Seberang Jaya – Simpang Ampat – Sungai Bakap – Bukit Tambun – Penaga – Permatang Tinggi

Outlying islets

There are a number of small islets off the coast of Penang, the biggest of which, Pulau Jerejak, is located in the narrow channel between Penang Island and the mainland. Starting as a leper asylum in 1868 and later a maximum-security penal colony (till 1993), Jerejak is now a tourist attraction offering jungle trails and a spa resort.[64] Other islands include Pulau Aman, Pulau Betong, Pulau Gedung, Pulau Kendi (Coral Island) and Pulau Rimau.

Greater Penang (conurbation of George Town)

The National Physical Plan of Malaysia envisages a Conurbation of George Town encompassing George Town and surrounding areas. The greater metropolitan area of Penang consists of highly urbanised Penang Island, Seberang Prai, Sungai Petani, Kulim and the surrounding areas. With a population of approximately two million, it is the second largest metropolitan area in Malaysia after the Conurbation of Kuala Lumpur (Klang Valley).[65]

George Town has been ranked as the most liveable city in Malaysia, eighth most liveable in Asia and the 62nd in the world in 2010 by ECA International, an improvement in ranking from recent years.[66]

Cityscape

Demographics

| 1786[67] | less than 100 | |

| 1812[68] | 26,107 | |

| 1820[68] | 35,035 | |

| 1842[68] | 40,499 | |

| 1860[68] | 124,772 | |

| 1871[68] | 133,230 | |

| 1881[68] | 188,245 | |

| 1891[68] | 232,003 | |

| 1901[69] | 248,207 | |

| 1911[70] | 278,000 | |

| 1921[71] | 292,484 | |

| 1931[72] | 340,259 | |

| 1941[73] | 419,047 | |

| 1947[73] | 446,321 | |

| 1957[72] | 572,100 | |

| 1970[74] | 776,124 | |

| 1980[74] | 900,772 | |

| 1991[74] | 1,064,166 | |

| 2000[74] | 1,313,449 | |

| 2010[74] | 1,520,143 | |

The state has the highest population density in Malaysia with 1,450.5 people per square kilometre[2] which would make it the 5th most densely populated in the country if Penang were a district. The population of Penang is 1,902,116 as of 2016.[3]

- Penang Island has a population of 711,102 in 2016 and a density of 2,372 people per square kilometre. Penang Island is the most populated island in Malaysia and has the highest population density in the country.

- Seberang Perai is the hinterland portion of Penang, populated by 906,077 people in the 2016, and has a density of 1,086 people per square kilometre.

The ethnic composition of Penang in 2015:[3]

| Ethnic groups in Penang, 2015 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | Population | Percentage |

| Chinese | 689,600 | 41.5% |

| Bumiputera | 693,100 | 41.7% |

| Indian | 166,000 | 10.0% |

| Others | 4,700 | 0.3% |

| Non-Malaysian | 103,300 | 6.2% |

Penang hosts an estimated 50,000 to 60,000 of migrant workers, mostly from Indonesia, Myanmar, Vietnam, Thailand, and South Asian nations who are mostly involved in domestic help, services, manufacturing, construction, plantations, and agriculture.[75]

During the colonial times, apart from the Europeans and the already multiracial citizenry, there were communities of Siamese, Burmese, Filipino, Ceylonese, Eurasian, Japanese, Sumatran, Arab, Armenian, and Parsee people.[76][77][78] A small but commercially significant community of German merchants also existed in Penang.[79] Even though most of these communities are no longer extant, they lent their legacy to street and place names such as the Burmese Buddhist Temple, Crag Hotel, Siam Rd, Armenian St, Acheen St, and Gottlieb Rd.

There was a Jewish enclave in Penang before World War II, but few Jews if any remain today.[80][81]

Penang currently has a sizeable expatriate population, especially from Singapore, Japan and various Asian countries as well as Britain, many of whom settle in Penang in their retirement as part of the Malaysia My Second Home programme.[82]

Peranakan

The Peranakan, also known as the Straits Chinese or Baba-Nyonya, are the descendants of the early Chinese immigrants to Penang, Malacca and Singapore.[83] They have partially adopted Malay customs and speak a Chinese-Malay creole of which many words contributed to Penang Hokkien as well (such as "Ah Bah" which means Mister, referring to a man as "Baba"). The Peranakan community possesses a distinct identity in terms of food, dress, rites, crafts and culture. Most of the Peranakan Chinese are not Muslims but practise an eclectic form of ancestor worship and Chinese religion, while some were Christians.[84] They prided themselves as being Anglophone and distinguished themselves from the newly arrived Chinamen or sinkheh.

While the Peranakan culture is still a living one, it is almost extinct today due to the Peranakans' re-absorption into the mainstream Chinese community. Many follow otherwise Westernised ways of life. Still, their legacy lives on in their distinctive architecture (exemplified by the Pinang Peranakan Mansion[85] and the Cheong Fatt Tze Mansion[86]), cuisine, elaborate nyonya kebaya costume and exquisite handicrafts.[87][88]

Language

The common languages of Penang, depending on social classes, social circles, and ethnic backgrounds are Malay, Mandarin, English, Penang Hokkien and Tamil. Standard Mandarin, which is taught in Chinese-medium schools in the state, is increasingly spoken.[89]

Malay, the language of the indigenous population, the official language of the state, as well as the medium of instruction of national schools, is spoken in the northern dialect, with characteristic words such as "hang", "depa", and "kupang". Syllables ending with "aq" are typically stressed.

Penang Hokkien is a variant of Minnan and is widely spoken by a substantial proportion of the Penang populace who are descendants of Chinese settlers. Many police officers also take a course in Hokkien.[90] It bears strong resemblance to the Hokkien dialect spoken by ethnic Chinese living in the Indonesian city of Medan and is based on the Minnan dialect of Zhangzhou, Fujian. It incorporates a large number of loanwords from Malay and English. Most Penang Hokkien speakers are not literate in Hokkien but instead read and write in standard (Mandarin) Chinese, English and/or Malay.[91] Other Chinese dialects, including Hakka and Cantonese are also spoken in the state, although they are less common. Teochew is heard more in Seberang Perai than on Penang island.

Tamil is spoken by the Indian community in Penang. Telugu, Punjabi and Malayalam is spoken by small number of people.

English, a colonial legacy, is a working language widely used in commerce, education, and the arts. English used in an official or formal context is predominantly British English with American influences. Spoken English, as in the rest of Malaysia, is often in the form of Manglish (Malaysian colloquial English).

Religion

As of 2010 the population of Penang is

- 44.6% Muslim,

- 35.6% Buddhist (in the Theravada, Mahayana and increasingly also Vajrayana traditions[93][94]),

- 8.7% Hindu. Mostly Saivism

- 5.1% Christian (Roman Catholicism and Protestantism, the largest denominations of which are the Methodists, Seventh-day Adventists, Anglican, Presbyterian and Baptists),

- 4.6% Taoist or Chinese religion follower,

- 1% follower of other religions or of unknown affiliation,

- 0.4% non-religious.

This reflects Penang's diverse ethnic and socio-cultural amalgamation. There was also a tiny and little-known community of Jews in Penang, mainly along Jalan Zainal Abidin (formerly Jalan Yahudi or Jewish Street).[95] The last known native Jew died in 2011, rendering the centuries-old Jewish community in Penang effectively extinct.[96][97]

Governance and law

The state has its own state legislature and executive, but they have relatively limited powers in comparison with those of the Malaysian federal government, chiefly in areas of revenues and taxation.

Executive

Penang, being a former British settlement, is one of only four states in Malaysia not to have a hereditary Malay Ruler or Sultan. The other three are Malacca, also a British settlement whose sultanate was ended by the Portuguese conquest in 1511, and the Borneo states of Sabah and Sarawak.

The head of the state executive is the Yang di-Pertua Negeri (Governor) appointed by the Yang di-Pertuan Agong (King of Malaysia). The present Governor is Tun Dato' Seri Haji Abdul Rahman bin Haji Abbas. His consent is required to dissolve the Legislative Assembly. In practice the Governor is a figurehead whose functions are chiefly symbolic and ceremonial.[98]

The Chief Minister of Penang is Lim Guan Eng from the Democratic Action Party (DAP). Following the 12th general elections of 8 March 2008, the coalition of DAP and Parti Keadilan Rakyat (PKR) formed the state government with the chief ministership going to the former for being the single largest party in the state legislature. Mr Lim Guan Eng is currently serving his second consecutive term as Chief Minister following his coalition's victory with two-thirds majority in the state legislature in the 2013 elections. Penang holds the distinction of being the sole state in Malaysia whose chief ministership has been continuously held by an ethnic Chinese since independence.

Local authorities

A committee of assessors was established in George Town in 1800 and was the first local authority established in Malaya.

On 1 January 1957, George Town became a city by a royal charter granted by Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, becoming the very first city in the Federation of Malaya and Malaysia (other than Singapore between the 1963 merger and its 1965 separation).

However, the George Town City Council was merged with the Penang Rural District Council to form the Penang Island Municipal Council in 1976.

In 2015, the entire Penang Island, including George Town, was granted city status by the Malaysian federal government. The former Municipal Council has been upgraded to the Penang Island City Council effective 1 January 2015.[99] A ceremony was held in March 2015, in which Dato' Patahiyah binti Ismail was installed as the mayor of Penang Island.[100] In effect, this makes George Town the only city in Malaysia to be given city status twice, first by Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, and then by the Malaysian federal government.

Though Penang in 1951 was the first state in the then Malaya to hold local elections, local councillors have been appointed by the Penang state government ever since local elections were abolished in Malaysia in 1965 as a result of the Indonesian Confrontation.[101]

There are currently two local authorities in Penang, the Penang Island City Council (Majlis Bandaraya Pulau Pinang) in charge of Penang Island and the Seberang Perai Municipal Council (Majlis Perbandaran Seberang Perai) in charge of Seberang Perai. The city council consists of a mayor, a secretary and 24 councillors, while the municipal council is made up of a president, a municipal secretary and 24 councillors. The president and mayor is appointed by the state government for a two-year term while the councillors are appointed for one-year terms of office.[102] The local councils are responsible, among others, for regulating traffic and parking, maintaining public parks, upkeeping cleanliness and drainage, managing waste disposal, issuing business licenses, and overseeing public health.

The state is divided into five administrative regions, each headed by a district officer:

- Penang Island:

- North-East Penang Island District (Daerah Timur Laut)

- South-West Penang Island District (Daerah Barat Daya)

- Seberang Perai:

- Northern Seberang Perai District (Daerah Seberang Perai Utara)

- Central Seberang Perai District (Daerah Seberang Perai Tengah)

- Southern Seberang Perai District (Daerah Seberang Perai Selatan)

Legislature

| Political Party/ Alliance |

State Legislative Assembly |

Dewan Rakyat |

|---|---|---|

| DAP, PKR & PAS | 30 (75%) | 10 (76.9%) |

| Barisan Nasional | 10 (25%) | 3 (23.1%) |

| Independent | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Source: Election Commission of Malaysia. | ||

The unicameral state legislature, whose members are called state assemblymen, convenes at the neoclassical Penang State Assembly Building (Dewan Undangan Negeri) at Light Street. It has 40 seats, 30 held by the Pakatan Rakyat coalition (of which 19 are held by the Democratic Action Party, ten by Parti Keadilan Rakyat, one by PAS), and 10 by the state opposition Barisan Nasional since the 2013 general elections. This was a one-seat improvement from the 2008 General Elections for the incumbent Pakatan Rakyat (PR) coalition government and has thus cemented PR's grip on the state. As in the national Parliament, Penang practises the Westminster system whereby members of the executive are appointed from amongst the elected assemblymen.

In the Malaysian Parliament, Penang is represented by 13 elected members of parliament in the Dewan Rakyat (House of Representatives), serving a five-year term, and has two senators in the Dewan Negara (Senate), both appointed by the state Legislative Assembly to serve a three-year term.

The Penang State Constitution embodies the state's highest laws which was codified since Independence. Amendments to the Constitution require a two-thirds majority support from members of the Assembly. The Malaysian Federal Constitution enumerates matters which come under federal, state, and joint jurisdictions. The state may legislate on matters pertaining to Malay customs, land, agriculture and forestry, local government, civil and water works, and state administration, whereas matters that fall under joint purview include social welfare, wildlife protection and national parks, scholarships, husbandry, town planning, drainage and irrigation, and public health and health regulations.[103][104]

Judiciary

The Malaysian legal system had its roots in 19th-century Penang. By 1807, a Royal Charter was granted to Penang which provided for the establishment of a Supreme Court. This was followed by the appointment of the first Supreme Court judge designated as the "Recorder". The Supreme Court of Penang was first housed at Fort Cornwallis and was opened on 31 May 1808.

The first Superior Court Judge in Malaya originated from Penang when Sir Edmond Stanley assumed office as the First Recorder (later, Judge) of the Supreme Court in Penang in 1808. The legal establishment in Penang was later progressively extended to the whole of British Malaya by 1951.[105]

Post-independence, the Malaysian judiciary has become largely centralised. The courts in Penang consist of the Magistrates and Sessions Courts, and the High Court. The court that is the highest up in the hierarchy of courts in Penang is the Penang High Court.

The Syariah court is a parallel court which hears matters concerning Islamic jurisprudence.

Economy

| Agriculture, hunting & forestry | 1.4 | 1.3 |

| Fishing | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Mining & quarrying | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| Manufacturing | 34.7 | 29.9 |

| Electricity, gas & water supply | 0.6 | 0.4 |

| Construction | 7.8 | 6.4 |

| Wholesale & retail trade; repair of motor vehicles, and personal & household goods |

14.0 | 17.6 |

| Hotels & restaurants | 9.4 | 8.7 |

| Transport, storage & communication | 5.1 | 7.2 |

| Financial intermediation | 2.2 | 3.0 |

| Real estate, renting & business activities | 5.5 | 6.7 |

| Public administration & defence; compulsory social security |

4.2 | 3.8 |

| Education | 4.9 | 5.1 |

| Health & social work | 3.5 | 2.8 |

| Other community, social & personal service | 2.9 | 2.6 |

| Private households with employed persons | 2.8 | 3.4 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 |

Industry

Penang is well known as the "Silicon Valley of the East" and is the third-largest economy amongst the states of Malaysia, after Selangor and Johor.[107] Penang is the state with the highest GDP per capita in Malaysia in 2010 with RM 33,456.00 (USD $10,893.00).[108] Manufacturing is the most important component of the Penang economy, contributing 45.9% of the state's GDP (2000). The southern part of the island is highly industrialised with high-tech electronics plants (such as Dell, Intel, AMD, Altera, Motorola, Agilent, Renesas, Osram, Plexus Corporation, Bosch and Seagate) in the Bayan Lepas Free Industrial Zone – earning Penang the nickname Silicon Island.[109] In January 2005, Penang was formally accorded the Multimedia Super Corridor Cyber City status, the first outside of Cyberjaya, with the aim of becoming a high-technology industrial park that conducts cutting-edge research.[110]

In recent years, however, the state is experiencing a gradual decline of foreign direct investments due to factors such as cheaper labour costs in China and India.[111][112] In 2010, Penang had the highest total of capital investments in the country. The state attracted RM 12.2 billion worth of investments, up fivefold from RM 2.2 billion the year before and a total increase of 465%. Other than that, Penang accounted 26% of Malaysia's total investments in 2010.[113]

In 2011, Penang became top in manufacturing investment in Malaysia for the second consecutive year, with RM9.1 billion in total. However, in a new measurement indicator of total investment introduced by MIDA, which comprises manufacturing, services and private sectors, Penang ranked second in Malaysia after Sarawak in total investments, with the total amount of RM14.038 billion. This was primarily due to not having sufficient primary sector investments. US media's Bloomberg described Penang's economic growth as Malaysia's "biggest economic success" despite the federal government's focus on other states such as Johor and Sarawak.[114] Consequently, after the economic success due to increase in total investments, the public debt in Penang decreased by 95% from RM630 million in 2008 to RM30 million at the end of 2011.[115]

The entrepôt trade has greatly declined, due in part to the loss of Penang's free-port status and to the active development of Port Klang near the federal capital Kuala Lumpur. However, there is a container terminal in Butterworth which continues to service the northern area.

Penang also has a small automotive industry. Butterworth-based Hong Seng Assembly (HSA) specialises in reconditioning and reassembly of heavy commercial vehicles.[116][117] As of the 2010s, the company has expanded their operations to include completely knocked down (CKD) assembly of new commercial vehicles from China.[118] Other important sectors of Penang's economy include tourism, finance, shipping and other services.

The Penang Development Corporation (PDC) is a self-funding statutory body aiming enhance Penang's socio-economic development and to create employment opportunities[119] whereas InvestPenang is a non-profit entity of the state government with the sole purpose of promoting investments in Penang.[120]

Agriculture

Agricultural land in 2008 is used for (in descending total area) oil palm (13,504 hectares), paddy (12,782), rubber (10,838), fruits (7,009), coconut (1,966), vegetables (489), cash crops (198), spices (197), cocoa (9), and others (41).[121] Two local produce for which Penang is famous for are durians and nutmegs. Livestock is dominated by poultry and domestic pigs. Other sectors include fisheries and aquaculture, and new emerging industries such as ornamental fish and floriculture.[122]

Owing to limited land size and the highly industrialised nature of Penang's economy, agriculture is given little emphasis. In fact, agriculture is the only sector to record negative growth in the state, contributing only 1.3% to the state GDP in 2000.[122] The share of Penang's paddy area to the national paddy area accounts for only 4.9%.[122]

Banking

Penang was the centre of banking of Malaysia at a time when Kuala Lumpur was still a small outpost. The oldest bank in Malaysia, Standard Chartered Bank (then the Chartered Bank of India, Australia and China) opened its doors in 1875 to cater to the financial requirements of early European traders.[123] The Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation, now known as HSBC, opened its first branch in Penang in 1885.[109] This was followed by the UK-based Royal Bank of Scotland (then ABN AMRO) in 1888. Most of the older banks still maintain their local headquarters on Beach Street, the historic commercial centre of George Town.

Today, Penang remains a banking hub of northern Malaysia, with branches of Citibank, United Overseas Bank, Bank of China,[124] Oversea-Chinese Banking Corporation and Bank Negara Malaysia (the Malaysian central bank) together with local banks such as Public Bank, Maybank, Ambank and CIMB Bank.

Culture and heritage

Jan/Feb | |

Birthday |

|

Heritage City Day |

|

the Koran Day |

|

(variable) | |

Performance Arts

There are two major Western orchestras in Penang – the Penang Philharmonic (formerly Penang State Symphony Orchestra and Chorus (PESSOC), and the Penang Symphony Orchestra (PSO).[125][126] The ProArt Chinese Orchestra is an orchestra playing traditional Chinese musical instruments.[127] There are also many other chamber and school-based musical ensembles. The Actors Studio at Straits Quay is a theatre group which started in 2002.[128] Dewan Sri Pinang and the Performing Arts Centre of Penang (Penangpac) at Straits Quay are two of the major performing venues in Penang.

Bangsawan is a Malay theatre art form (often referred to as the Malay opera) which originated from India, developed in Penang with Indian, Western, Islamic, Chinese and Indonesian influences. It went into decline in the latter decades of the 20th century and is a dying art form today.[129][130] Boria is another traditional dance drama indigenous to Penang featuring singing accompanied by violin, maracas and tabla.[131]

Chinese opera (usually the Teochew and Hokkien versions) is frequently performed in Penang, often in specially built platforms, especially during the annual Hungry Ghost Festival. There are also puppetry performances although they are less performed today.

Street Art

In 2012, as part of the Georgetown Festival of Arts and Culture, Lithuanian Artist Ernest Zacharevic created a series of 6 wall paintings depicting local culture, inhabitants and lifestyles.[132] They now stand as celebrated cultural landmarks of George Town, with Children on a Bicycle being one of the most photographed spots in the area.

With these murals, the street art scene has blossomed. Cultural centres such as the Hin Bus Depot are now curating exciting exhibitions and inviting international artists to visit and paint murals, building on the existing reputation the city has as a vibrant arts and culture centre. The art scene is growing beyond this, too, in the funny and entertaining 'Marking George Town' exhibition of wrought iron caricatures waiting to be discovered among the streets.

Museums and galleries

The Penang Museum and Art Gallery, in George Town, houses relics, photographs, maps, and other artefacts that document the history and culture of Penang and its people.[133] The Penang Islamic Museum at the former Syed Alatas Mansion highlights the history of Islam in Penang from its beginnings until today. The tragedy of the Second World War is vividly depicted in the Penang War Museum, a former fortress constructed by the British in anticipation of an amphibious invasion by the Japanese that never materialised. The Universiti Sains Malaysia Museum and Gallery, located within the university campus contains an extensive exhibition relating to ethnographic and performing arts, and features various art works by Malaysian artists.[134] Also, Penang Toy Museum is located at Tanjung Bungah and there is a forestry museum within the Teluk Bahang Forest Park.[135] The Penang State Art Gallery at Dewan Sri Pinang showcases a permanent collection of local artists as well as special exhibitions. The birthplace of Malaysia's legendary singer-actor P. Ramlee has been restored and turned into a museum.[136] Penang also houses other museums such as the Camera Museum, Batik Painting Museum and Sun Yat-sen Museum.

Architecture

The architecture of Penang is a durable testament of her history – a culmination of over a century and a half of British presence, as well as the confluence of immigrants and the culture they brought with them. Fort Cornwallis was the first structure the British built in Penang.[137][138] Outstanding examples of colonial period buildings include the Municipal Council and Town Hall buildings, the buildings in the old commercial district, the Penang Museum, the Eastern and Oriental Hotel, and St George's Anglican Church – all of which are part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The Suffolk House, the former residence of Penang's British governors, on the banks of the Air Itam river is an example of the Anglo-Indian garden house.[139] The stately Seri Mutiara (formerly known as the Residency), completed in 1890 as the residence of Penang's British Resident Councillors, is today the official residence of the Governor.[140]

Chinese influence is visible at the many ornate clan houses, temples, pre-war shophouses, and mansions such as the Cheong Fatt Tze Mansion. The Clan Jetties are a collection of water villages at Weld Quay. The Indian community built many elaborate temples such as the Mahamariamman temple, while Muslim influence can be seen at the Kapitan Keling Mosque, the Acheh Mosque, and the Penang Islamic Museum. The P. Ramlee Museum is an excellent example of traditional Malay stilt houses. Siamese and Burmese architecture can be appreciated at the Sleeping Buddha and Dharmikarama temples.

Modern structures and skyscrapers also abound in Penang, sometimes side by side with heritage buildings. Notable examples include the KOMTAR tower, and the Gurney Paragon Towers.

Festivals

The cultural mosaic of Penang naturally means that they are a great many number of festivals to celebrate. The Chinese celebrate, among others, the Chinese New Year, Mid-Autumn Festival, Hungry Ghost Festival, Qing Ming, and the feast days of various deities. The Malays and Muslims celebrate Hari Raya Aidilfitri, Hari Raya Haji, and Maulidur Rasul while the Indians observe Deepavali, Thaipusam and Thai Pongal. Christmas, Good Friday and Easter are celebrated by Christians. The annual Saint Anne's Novena and Feast Day draws thousands of Catholics to St. Anne's Church in Bukit Mertajam.[141][142] Buddhists observe Wesak Day while the Sikhs celebrate Vaisakhi. Many of these festivals are celebrated in a large scale and are also public holidays in Penang.

Bon Odori is an annual event held at the Esplanade by the expatriate Japanese population.

The Penang Government organises the annual George Town Festival which celebrates the city's World Heritage Site status with arts and live cultural performances throughout the month of July. The famous Pesta Pulau Pinang (Penang Fest) is a combination of trade expo, family-oriented carnival and cultural events held throughout the month of December since the 1960s primarily at the Pesta site in Sungai Nibong and other locations in the state.[143]

Food

Penang, long known as the food capital of Malaysia, is renowned for its good and varied food.[144][145][146][147] Penang was recognised as having the Best Street Food in Asia by Time magazine in 2004, citing that "nowhere else can such great tasting food be so cheap".[148] Penang's cuisine reflects the Chinese, Nyonya, Malay and Indian ethnic mix of Malaysia, but also shows some influence of Thailand. Its especially famous "hawker food", many served al fresco, strongly features noodles, spices, and fresh seafood.

The best places to savour Penang's food include Gurney Drive, Pulau Tikus, New Lane, New World Park, Penang Road and Chulia Street, as well as Raja Uda and Chai Leng Park over on the mainland. Penang is also famed for its traditional biscuits such as the tau sar pneah (bean paste biscuit). Aside from that, Penang is also ranked among top ten greatest street food cities in Asia, according to CNN Go.[149] In 2014, Penang has been voted by Lonely Planet as the top food destination.[150]

Tourism

Visited by Somerset Maugham, Rudyard Kipling, Noël Coward and Queen Elizabeth II among many others, Penang has always been a popular tourist destination, both domestically and internationally.[151][152][153] In 2009, Penang attracted 5.96 million tourists, ranking third in tourist arrivals in Malaysia.[154] Penang is known for its rich heritage, multicultural society and its vibrant culture, its hills, parks, and beaches, shopping, and good food. There are a variety of accommodation options from guest houses and budget hotels to four- and five-star hotels. For staying at a room for one night, guests are required to pay a bed tax around RM2 to RM3.[155]

Penang has been ranked by Yahoo! Travel as one of the "10 Islands to Explore Before You Die"[156] and listed in Patricia Schultz's best-selling 1,000 Places to See Before You Die travel book.[157]

Beaches

The most popular beaches in Penang are located at Tanjung Bungah, Batu Ferringhi, and Teluk Bahang, and these contiguous beaches are home to Penang's famed hotel and resort belt. More secluded Muka Head, which hosts a lighthouse and a marine research station, and Monkey Beach – both within the Penang National Park – offer more pristine water.

Pollution which has been going on for years taints the beauty of the beaches and increasingly turns tourists away to places like Langkawi and Pangkor. Among the identified sources of pollution include inefficient sewage disposal and unchecked commercial activities.[158][159]

Food

Famed for its food, Penang is a food haven visited by the Malaysian locals as well as foreign tourists. Touted the food capital of Malaysia, some of the best of Penang food can be found at Gurney Drive. The popular seafront promenade offers both delightful street and high-end cuisine. At the food court, you can find local favourites such as Char Kway Teow (fried flat noodles with prawns), Penang Laksa (sour and spicy fish soup served with noodles and mint leaves) Bak Kuk Teh (a herbal stew of pork ribs and meat), Oh Chien (fried oyster omelette), grilled squid, and nasi lemak. The food court has both a halal and non-halal section.[160]

In 2014, Penang was named the top food destination in the world by Robin Barton of Lonely Planet. Penang was described as "Its food reflects the intermingling of the many cultures that arrived after it was set up as a trading port in 1786, from Malays to Indians, Acehenese to Chinese, Burmese to Thais. State capital Georgetown is its culinary epicentre."[161]

Heritage and culture

The Cheong Fatt Tze Mansion was built in the 1880s by master craftsmen brought in especially from China. The famous indigo-blue Chinese Courtyard House in George Town was the residence of Cheong Fatt Tze, and was built with 38 rooms, 5 granite-paved courtyards, 7 staircases and 220 windows and possesses splendid Chinese timber carvings, Gothic louvre windows, russet brick walls and porcelain cut & paste decorative shard works, art nouveau stained glass panels, Stoke-on-Trent floor tiles and Scottish cast iron work. It is filled with rare a collection of sculptures, carvings, tapestries and other antiques.[162]

Also known as the Temple of Supreme Bliss, Kek Lok Si is said to be the largest Buddhist temple in Southeast Asia. Its main draw is the striking seven-storey Pagoda of Rama VI (Pagoda of 10,000 Buddhas) and 30.2m bronze statue of Kuan Yin, the Goddess of Mercy.[163]

The Pinang Peranakan Mansion is the former residence and office of Chinese Kapitan Chung Keng Kwee, and incorporates various Chinese architecture. Here you can find more than 1,000 antiques and collectibles.[164]

Historical

Fort Cornwallis, named after Charles Cornwallis, is one of the historical landmarks in George Town. The fort's walls are roughly 10 feet tall and shaped like a star. Some of the original structures built over a century ago are still standing, such as a chapel, prison cells, ammunitions storage area, a harbour light once used to signal incoming ships, the original flagstaff and several old bronze cannons, one of which is a Dutch cannon called the Seri Rambai, dated 1603.[165]

The Penang War Museum was erected on the original defence complex built by British before World War II and is dedicated to those who have served and died, defending the country. Many war paraphernalias and relics, as well as historical timelines of events are on exhibit at the museum.[166]

Parks, gardens and natural history

Despite its limited land size and dense population, Penang has managed to retain a considerable area of natural environment. As of 2011, 7% of the state's total surface area or 7524 hectares was forested.[167] Located at the fringe of George Town, at the foot of Penang Hill are two adjacent green areas – the Penang Municipal Park (popularly known as Youth Park) and the Penang Botanic Gardens. Penang Hill, despite encroaching development, remains thickly forested and lush in vegetation.[168] The Relau Metropolitan Park was opened in 2003. Robina Beach Park is a park by the beach near Butterworth.

Gazetted in 2003, the Penang National Park (the country's smallest at 2,562 hectares) at the northwestern tip of Penang island boasts of a lowland dipterocarp forest, mangroves, wetlands, a meromictic lake, mud flats, coral reefs and turtle nesting beaches in addition to a rich diversity of birdlife.[169] In addition to this, there are nature preserves in Bukit Relau, Teluk Bahang, Bukit Penara, Bukit Mertajam, Bukit Panchor, and Sungai Tukun. The Penang Butterfly Farm in Teluk Bahang, one of few of its kind in the world, is a walk-in free-ranging butterfly habitat, breeding and conservation centre.[170] The Penang Bird Park in Seberang Jaya is the first aviary in Malaysia.[171] Other places of special interest include the Tropical Spice Garden and the Tropical Fruit Farm in Teluk Bahang, and the Bukit Jambul Orchid and Hibiscus Garden.

A small bushy tree, Alchornea rhodophylla, the almost-extinct tree Maingaya malayana, and the toad Ansonia penangensis are endemic to the island of Penang.[172][173][174] Some of the commonly seen birds in Penang include the migratory greater spotted eagle (Aquila clanga), the blue-tailed bee-eater (Merops philippinus) and the blue-throated bee-eater (Merops viridis), and the endemic chestnut-headed bee-eater (Merops leschenaulti), the brahmniy kite (Haliastur indus), the common sandpiper (Actitis hypoleucos), and the white-bellied sea eagle.[175][176][177] The sandy beaches of Penang National Park are the nesting grounds for the green turtle (Chelonia mydas) from April to August, and the olive ridley sea turtle (Lepidocchelys olivacea) between September and February. The Irrawaddy dolphin (Orcaella brevirostris) and the bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) are occasionally sighted in the coastal seas off the park.[177] Also living in the park are the leopard cat (Prionailurus bengalensis), the flying lemur (Galeopterus variegatus), and one of the world's largest arboreal rodents, the cream-coloured giant squirrel (Ratufa affinis))[177][178]

Education

Schools

Penang was a pioneer in education in Malaysia, having some of the earliest established schools in the country. The public school system comprises national schools, vernacular (Chinese and Tamil) schools, vocational schools, and religious schools. There are also a few international schools, such as Dalat International School, Tenby International School, Prince of Wales Island International School, The International School of Penang, the Penang Japanese School, and St. Christopher's International Primary School for both expatriates' and Malaysian children. The state has five Chinese Independent High Schools:[179] Penang Chinese Girls' Private High School, Chung Ling Private High School, Phor Tay Private High School, Han Chiang School and Jit Sin Independent High School.

Former missionary schools

Formal education in Penang stretches back to the early days of British administration. Many of the public schools in Penang are among the oldest in the country and even in the region as a whole but has since been turned into national schools. They educated generations of important personages in the country's history, which included royalty, ministers, lawmakers, sportsmen, artists, and musicians. Most notable of these are Penang Free School (est. 1816, the oldest English school in the country),[180] St. Xavier's Institution (est. 1852), Convent Light Street (est. 1852, the first school for girls in Malaysia), Methodist Boys' School (est. 1891) and Methodist Girls' School (est. 1891).

Chinese schools

Penang has long been the centre of a well-developed Chinese-language schooling system. These schools were set up by local Chinese associations with donations from philanthropists, and have historically attracted students from Chinese communities in Thailand and Indonesia, where Chinese education was banned. These schools are well-supported by the community and many consistently produce good results, thus attracting non-Chinese students too. There are 90 Chinese primary schools,10 Chinese secondary schools, and 5 Chinese independent high school in Penang. Among them are:

Public Schools

- 槟城孔圣庙中华中学 Chung Hwa Confucian School (est. 1904, the first Mandarin Chinese school in Malaysia)

- 槟城锺灵国民型中学Chung Ling High School (established 1917)

- 北海锺灵国民型中学 Chung Ling Butterworth High School

- 大山脚日新国民型华文中学Jit Sin High School (est. 1918)

- 协和国民型中学 Union High School (est. 1928)

- 菩提国民型中学Phor Tay High School (est. 1940, the first Buddhist school in Malaysia)

- 恒毅国民型中学Heng Ee High School (1957)

- 槟城修道院国民型中学 Convent Datuk Keramat High School

- 圣心国民型中学 Sacred Heart high school

- 槟华国民型女子中学 Penang Chinese Girls High School

Private Schools

- 槟城锺灵独立中学 Chung Ling (Private) High School, Penang

- 槟城韩江中学 Han Chiang High School, Penang (est. 1919)

- 大山脚日新独立中学 Jit Sin Independent High School, Bukit Mertajam

- 槟城槟华女子独立中学 Penang Chinese Girls' Private High School, Penang (est. 1920)

- 槟城菩提独立中学 Phor Tay Private High School, Penang

National, vocational, and religious schools

National schools use Malay as their medium of instruction. Unlike early Chinese and missionary schools, national schools are mostly built and funded by the government. The student population in these schools tend to be more multiracial. Examples are Bukit Jambul Secondary School, Sri Mutiara Secondary School and Air Itam Secondary School. The Tunku Abdul Rahman Technical Institute and the Batu Lanchang Vocational School are two of Penang's vocational schools. The Al-Mashoor School is a religious school in Penang.

International schools

- The International School of Penang (Uplands)

- Chinese Taipei School Penang

- Penang Japanese School (ペナン日本人学校)

Colleges and universities

.jpg)

Penang is home to two medical schools (Penang Medical College and Allianze College of Medical Sciences), a nursing college, a dental training college, two Institute of Teacher Education Malaysia campuses (Bukit Chombee Campus and Tuanku Bainun Campus), and numerous private and community colleges. The two public universities in Penang are Universiti Sains Malaysia at Gelugor and its Engineering campus at Nibong Tebal, and Universiti Teknologi MARA at Permatang Pauh.[181][182] The former, popularly known by its acronym USM, is one of Malaysia's earliest universities, and is today accorded the status of apex university dedicated to research. Wawasan Open University is a private university which has both distance-learning and on campus programs.[183] Penang also hosts SEAMEO RECSAM, a research and training facility for the enhancement of the science and mathematics education in Southeast Asia. Some of the colleges in Penang include Tunku Abdul Rahman University College (TARUC), Han Chiang College, KDU College, The One Academy Penang, Inti College, DISTED College, SEGi College and Olympia College.

Libraries

The Penang Public Library Corporation in 1973 replaced the Penang Library which in turn was set up in 1817.[184] It operates the main Penang Public Library in Seberang Prai, the George Town Branch Library, the Children's Library, and three smaller libraries.[185]

Media

The mainstream newspapers in Penang include the English dailies The Star, The New Straits Times, and the free The Sun; the Malay dailies Berita Harian, Utusan Malaysia, Harian Metro, and Kosmo!; the Chinese dailies Kwong Wah Yit Poh, Sin Chew Daily, China Press, and Oriental Daily News; and the Tamil dailies Tamil Nesan, Malaysia Nanban, and Makkal Osai. The Malay Mail is an English weekly. Nanyang Siang Pau is a Chinese-language financial daily while The Edge is an English-language financial weekly newspaper. All of them are in national circulation. In 2011, Chief Minister of Penang Lim Guan Eng officiated the launch of Time Out Penang.[186] The Penang edition of the international listings magazine is currently published in three versions: a yearly printed guide, a regularly updated website, and mobile app.[187]

Health care

Health care in Penang is provided by public as well as private hospitals. The public health care system first established by the colonial authorities was supplemented by health care provided by local Chinese charities, and Christian missionaries such as the Roman Catholic and the Seventh-day Adventist.

Today public hospitals are funded and administered by the Ministry of Health. The Penang Hospital is a tertiary-care regional referral centre. In addition to public hospitals are numerous smaller community clinics (klinik kesihatan) and private practices. Private hospitals supplement the system with better facilities and speedier care. These hospitals cater not only to the local population but also to patients from other states and health tourists from neighbouring countries such as Indonesia.[188] Penang is actively promoting health tourism. In 2010, 250,000 foreign patients were treated. The state earned an estimated RM 230 million through medical tourism in 2010, up from RM 162 million in 2009. Penang also contributed 70% to Malaysia's medical tourism revenue.[189] Hospices are also increasingly becoming the choice for long-term and terminal care. Infant mortality rate at present is 0.4% while life expectancy at birth is 71.8 years for men and 76.3 years for women.[190]

|

Public hospitals Penang Island

Seberang Perai

|

Private hospitals Penang Island

Seberang Perai

|

Transportation

Getting to Penang both from within and outside Malaysia is easy as Penang is well-connected by road, rail, sea and air. Flights are available from Kuala Lumpur to Penang by local and regional carriers such as AirAsia and Tigerair.[191]

Bridges, roads and highways

Penang Island is connected to the mainland by two bridges. The first one is the 13.5 km (8.4 mi), three-lane, dual carriageway Penang Bridge, which was completed in 1985. The Second Penang Bridge is located further south, linking Batu Maung on the southeastern part of the island to Batu Kawan on the mainland. It was opened to the public in early 2014 and is currently the longest bridge in Southeast Asia.

The North-South Expressway (Lebuhraya Utara-Selatan), a 966-km long expressway which traverses the western part of Peninsular Malaysia linking major cities and towns, passes through Seberang Perai. After exiting either one of both bridges, commuters can directly use the expressway to get to the rest of Peninsular Malaysia.

The Tun Dr Lim Chong Eu Expressway formerly known as the Jelutong Expressway, a coastal highway on the eastern part of the island, links the Penang Bridge to George Town.

The Butterworth Outer Ring Road (BORR) is a 14-km tolled expressway that serves primarily Butterworth and Bukit Mertajam to ameliorate the upsurge in vehicular traffic due to intense urban and industrial development.

Public transport

One of the earliest modes of transportation in Penang was the horse hackney carriage which was popular throughout the last quarter of the 18th century until 1935, when the rickshaw (jinriksha) gained popularity, until it in turn was rapidly superseded by the trishaw beginning in 1941 and still used in George Town today, mostly for sightseeing rides, albeit in much lesser numbers.[18][192]

Horse trams, steam trams, electric trams, trolleybuses and double deckers used to ply the streets of Penang. The first steam tramway started operations in the 1880s and for a time horse-drawn cars were also introduced. Electrical trams were launched in 1905. Trolleybuses commenced in 1925 and they gradually supplanted the trams but they in turn were discontinued in 1961 and regular buses henceforth became the only form of public transport to this day.[193][194]

For a long time, public bus services were deemed unsatisfactory.[195][196][197] In 2007, the government announced that Rapid KL would take over all public bus services in Penang under the new entity called Rapid Penang which is formed for this purpose.

Rapid Penang started out with 150 buses covering 28 routes on the island and mainland. This service has since been extended. After Rapid Penang came in, public transportation in Penang has improved. Public transportation usage in the state has also increased from a lowly 30,000 commuters a day in 2007 to 75,000 commuters a day in 2010.[198] Currently, there are 350 buses plying 41 routes around the state (30 routes on Penang Island, 9 routes on Seberang Prai and 2 routes connecting Penang Island and Seberang Prai). However, usage of public transport remains low, contributing to traffic jams in the city during rush hours.[199]

In light of this, the city council has introduced free shuttle bus services for short intra-city travel to lessen the congestion.[195] This bus service, which runs within George Town, also serves tourists seeking cheap and quick transport throughout the heritage enclave. Recently, open-air double decker buses, known as Hop-On Hop-Off buses, are introduced for tourists in George Town.[200]

There are two main bus terminals for express coaches travelling out of and into Penang. One is located at Penang Sentral in Butterworth, and another at Sungai Nibong on the island.

Taxis in Penang do not use the meter as required by the Commercial Vehicle Licensing Board but instead charge fixed fares.[201]

Rail and monorail

George Town used to operate both trams and trolleybuses. The tramway system being steadily replaced in the mid-20th century by trolleybuses, first introduced in 1925. In the 1950s, ex-London Transport trolleybuses were brought into the city. Despite having purchased new Sunbeam British trolleybuses in 1956/7, the system was abandoned in 1961. The use of double-decker buses ceased in the 1970s; since then, buses dominate the public transportation system in Penang.

Penang has 34.9 km (21.7 mi) of rail track within its border.[202] The Butterworth railway station is serviced by the Keretapi Tanah Melayu (KTM) which runs from Padang Besar on the Malaysia-Thailand Border to Singapore. Senandung Langkawi is the daily night express running from Kuala Lumpur to Haadyai via Butterworth.

The Penang Hill Railway, a funicular railway to the top of Penang Hill, is the only cable car rail system of its kind in Malaysia. It was an engineering feat of sorts when completed in 1923. The railway underwent an extensive upgrading in 2010 and was reopened in early 2011.[203]

Beginning 2015, the Penang Transport Master Plan is to be implemented by the Penang state government. The plan envisages, among others :

– the return of trams in the streets of George Town,[204]

– Light Rail Transit (Penang Rapid Transit) lines from Komtar to the Penang International Airport and the suburbs of Air Itam, Paya Terubong and Tanjung Tokong,[205] and

– an overhead cable car linking Komtar to the Penang Sentral in Butterworth.[206]

With the completion of the plan in 2030, the Penang state government aims to have multiple public transportation systems on the ground, at sea and even in the air.

Airport

Penang International Airport (PEN) is located at Bayan Lepas to the south. The airport serves as the northern gateway to Malaysia and is the secondary hub of Firefly, a low-cost carrier wholly owned by Malaysia Airlines as well as AirAsia, a pioneer low-cost carrier from Malaysia. Other airlines operating at Penang are national flag carrier Malaysia Airlines, SilkAir (a subsidiary of Singapore Airlines), Thai Airways International, Tiger Airways, Jetstar Asia Airways, Hong Kong-based Dragonair, Taiwan-based China Airlines, China Southern Airlines, together with Indonesian airlines Lion Air, Sriwijaya Air and Wings Air.

Penang Airport has direct flights to other Malaysian cities, namely Kuala Lumpur, Kuching, Kota Kinabalu, Johor Bahru, Langkawi, Kota Bharu and regular connections to major Asian cities such as Singapore, Bangkok, Jakarta, Hong Kong, Taipei and Guangzhou.

The airport also serves as an important cargo hub due to the large presence of multinational factories in the Free Trade Zones as well as catering to the northern states of peninsular Malaysia.

Ferry and seaports

Cross-channel ferry services, provided by the Penang Ferry Service, connect George Town and Butterworth, and were the only link between the island and the mainland until the bridge was built in 1985.[207] High-speed ferries to the resort island of Langkawi, Kedah in the north as well as to Medan are also available daily.

The Port of Penang is operated by the Penang Port Commission. There are four terminals, one on Penang island (Swettenham Pier) and three on the mainland, namely North Butterworth Container Terminal (NBCT), Butterworth Deep Water Wharves (BDWW), and Prai Bulk Cargo Terminal (PBCT). With Malaysia being one of the largest exporting nations in the world,[208] the Port of Penang plays a leading role in the nation's shipping industry, linking Penang to more than 200 ports worldwide. The Swettenham Pier Port also accommodates cruise ships and on occasions, warships.

Utilities

Water supply which comes under the state jurisdiction, is wholly managed by the state-owned but autonomous PBA Holdings Bhd whose sole subsidiary is the Perbadanan Bekalan Air Pulau Pinang Sdn Bhd (PBAPP). This public limited company provides reliable, round-the-clock drinking water throughout the state. Penang was cited by the World Development Movement as a case study in successful public water scheme.[209] PBA's water rates are also one of the lowest in the world[210] Penang's water supply is sourced from the Air Itam Dam, Mengkuang Dam, Teluk Bahang Dam, Bukit Panchor Dam, Berapit Dam, Cherok Tok Kun Dam, Waterfall Reservoir (at the Penang Botanic Gardens), Guillemard Reservoir, and also from the Muda River of Kedah.

Penang was among the first states in Malaya to be electrified in 1905 upon the completion of the first hydroelectric scheme.[24] At present, electricity for industrial and domestic consumption is provided by the national electricity utility company, Tenaga Nasional Berhad (TNB).

Telekom Malaysia Berhad is the landline telephone service provider and an Internet service provider (ISP) in the state. Mobile network operators and mobile ISPs include Maxis, Digi, Celcom, and U Mobile.