Postpartum psychosis

| Postpartum psychosis | |

|---|---|

| Synonyms | puerperal psychosis |

| |

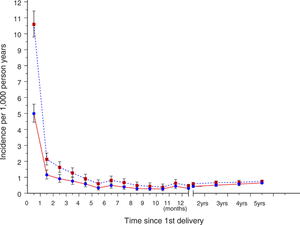

| Rates of psychoses among Swedish first-time mothers | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | psychiatry |

| ICD-10 | F53.1 |

| ICD-9-CM | 648.4 |

Postpartum psychosis is a rare psychiatric emergency in which symptoms of high mood and racing thoughts (mania), depression, severe confusion, loss of inhibition, paranoia, hallucinations and delusions set in begin suddenly in the first two weeks after delivery. The symptoms vary and can change quickly.[1] The most severe symptoms last from 2 to 12 weeks, and recovery takes 6 months to a year.[1]

About half of women who experience it have no risk factors; but women with a prior history of mental illness, especially bipolar disorder, a history of prior episodes of postpartum psychosis, or a family history, are at a higher risk.[1] It is a not a formal diagnosis, but is widely used to describe a condition that appears to occur in about 1 in a 1000 pregnancies. It is different from postpartum depression and from maternity blues.[2] It may be a form of bipolar disorder.[3]

It often requires hospitalization, where treatment is antipsychotic medication, mood stabilizers, and in cases of strong risk for suicide, electroconvulsive therapy.[1] Women who have been hospitalized for a psychiatric condition immediately after delivery are at a much higher risk of suicide during the first year after delivery.[4]

There is a need for further research into the causes and prevention; the lack of a formal diagnostic category and the difficulty of conducting clinical trials in pregnancy hinder research.[1]

Classification

Postpartum psychosis is a psychiatric emergency related to care of women after they give birth.[1][2] It is different from postpartum depression and from maternity blues.[2]

The condition is not recognized in the DSM-5 nor in the ICD-10 but it is widely used clinically.[1]

It may be a form of bipolar disorder.[3]

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms usually begin suddenly in the first two weeks after delivery.[2] Symptoms vary and can change quickly, and can include high mood and racing thoughts (mania), depression, severe confusion, losing inhibitions, paranoia, hallucinations and delusions.[2]

In contrast, about half of women have the maternity blues after birth, which is characterized by symptoms of mild mood swings, anxiety, and irritability that start about 3 to 4 days after delivery and last about a week; postpartum depression is also different — it is experienced by 10 to 15% of women after birth and is similar to major depressive disorder.[2]

Risk factors

25 to 50% of women with a history of mental illness experience postpartum psychosis;[2] around 37% of women with bipolar disorder have a severe postpartum episode.[3] Women with a prior episode of postpartum psychosis have about a 30% risk of having another episode in the next pregnancy.[3]

There appears to be a genetic component because the risk of postpartum psychosis for a woman with a close relative (a mother or sister) who had postpartum psychosis is about 33%[2] and for women who have both a personal history of mental illness and a family history, the risk is 70%.[4] However, while mutations in chromosome 16 and in specific genes involved in serotoninergic, hormonal, and inflammatory pathways have been identified, none had been confirmed as of 2014.[1]

About half of women who experience postpartum psychosis had no risk factors.[1] Many other potential factors like pregnancy and delivery complications, caesarean section, sex of the baby, length of pregnancy, changes in psychiatric medication, and psychosocial factors, have been researched and no clear association has been found; the only clear risk factor identified as of 2014, was that postpartum psychosis happens more often to women giving birth for the first time, than to women having second or subsequent deliveries, but the reason for that was not known.[1] There may be a role for hormonal changes that occur following delivery, in combination with other factors; there may be a role changes in the immune system as well.[1]

Prevention and screening

For women taking psychiatric medication, the decision as to whether continue during pregnancy and whether to take them while breast feeding is difficult in any case; there is no data to guide this decision with respect to preventing postpartum psychosis.[2] There is no data to guide a decision as to whether women at high risk for postpartum pyschosis should take antipsychotic medicine to prevent it.[2] For women at risk of postpartum psychosis, informing medical care-givers, and monitoring by a psychiatrist during pregnancy, in the perinatal period, and for a few weeks following delivery, is recommended.[2]

For women with known biopolar disorder, taking medication during pregnancy roughly halves the risk of a severe postpartum episode, as does starting to take medication immediately after the birth.[3]

Management

In most cases hospital admission is necessary.[2] Antipsychotic drugs and mood stabilizing drugs such as lithium are typically administered[2] but is not clear if mood stabilizers can be titrated to a high enough level quickly enough to be effective.[1] Electroconvulsive therapy may be considered, especially if there is a high risk of suicide.[1]

Family support may be provided via a social worker.[2]

Outcomes

The most severe symptoms usually last from 2 to 12 weeks; it can take between six months to a year to recover.[2]

Women often experience low self-esteem and difficulties as they recover, but many women fully recover; many women also have a hard time bonding with their child as they recover, but end up with healthy relationships with their babies.[2]

About half of women who experience postpartum psychosis have further experiences of mental illness unrelated to childbirth; further pregnancies do not change that risk.[2]

Women who have been hospitalized for a psychiatric illness shortly after giving birth have a 70 times greater risk of suicide in the first year after they gave they birth.[4]

Epidemiology

Postpartum psychosis occur in around 1 in 1000 deliveries,[2] but this figure is uncertain due to the lack of diagnostic categories for tracking in databases.[1]

History

Puerperal mania was first clearly described by the German obstetrician Friedrich Benjamin Osiander in 1797,[5] and a literature of over 2,000 works has accumulated since then.

The French psychiatrist Louis-Victor Marcé (1862), suggested that the menstrual cycle is important and drew parallels with menstrual psychosis.[6]

Episodes of postpartum psychosis used to be explained by eclampsia, "delirium", thyroid disorders, or infection.[1]

Society and culture

Support

In the UK, a series of workshops called "Unravelling Eve" were held in 2011, where women who had experienced postpartum depression shared their stories.[7]

Notable cases

Harriet Sarah, Lady Mordaunt (1848–1906) formerly Harriet Moncreiffe, was the Scottish wife of an English baronet and Member of Parliament, Sir Charles Mordaunt.[8] She was the defendant in a sensational divorce case in which the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII) was embroiled; after a controversial trial lasting seven days, the jury determined that Lady Mordaunt was suffering from “puerperal mania” and her husband's petition for divorce was dismissed, while Lady Mordaunt was committed to an asylum.[9]:36–37

Legal status

Several nations including Canada, Great Britain, Australia, and Italy recognize postpartum mental illness as a mitigating factor in cases where mothers kill their children.[10] In the United States, such a legal distinction was not made as of 2009.[10] Britain has had the Infanticide Act since 1922.

Research directions

The lack of a formal diagnosis in the DSM and ICD has hindered research.[1] The causes of postpartum depression are unknown and are under investigation.[1][2]

There is a need to better understand whether taking medication prophylactically during pregnancy or immediately following the birth, and specifically what kinds, what dosing, and what timing, could prevent postpartum psychosis; typical randomized controlled clinical trials would be difficult to implement so retrospective studies would most likely to be most useful — this in turn would require careful data keeping.[3]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Jones, I; Chandra, PS; Dazzan, P; Howard, LM (15 November 2014). "Bipolar disorder, affective psychosis, and schizophrenia in pregnancy and the post-partum period.". Lancet. 384 (9956): 1789–99. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61278-2. PMID 25455249.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 "Postpartum Psychosis". Royal College of Psychiatrists. 2014. Retrieved 27 October 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Wesseloo, R; Kamperman, AM; Munk-Olsen, T; Pop, VJ; Kushner, SA; Bergink, V (1 February 2016). "Risk of Postpartum Relapse in Bipolar Disorder and Postpartum Psychosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.". American Journal of Psychiatry. 173 (2): 117–27. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15010124. PMID 26514657.

- 1 2 3 Orsolini, L; et al. (12 August 2016). "Suicide during Perinatal Period: Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Clinical Correlates.". Frontiers in psychiatry. 7: 138. PMC 4981602

. PMID 27570512.

. PMID 27570512. - ↑ Osiander, Friedrich Benjamin (1797). "Glücklich gehobenes hitziges Fieber einer Wöchnerin mit Wahnsinn" [Happy young mother with a violent fever upscale madness]. Neue Denkwuerdigkeiten fuer Aerzte und Geburtshelfer [New memoirs for physicians and obstetricians] (in German). 1. Goettingen: Rosenbusch. pp. 52–128.

- ↑ Marcé, L V (1862). Traité Pratique des Maladies Mentales [Practical Treatise on Mental Illness] (in French). Paris: Martinet. p. 146.

- ↑ Dolman, Clare (4 December 2011). "When having a baby can cause you to 'lose your mind'". BBC News.

- ↑ "Person Page: Harriett Sarah Moncreiffe". thepeerage.com. Retrieved 27 October 2016.

- ↑ Souhami, Diana (1996). Mrs. Keppel and her daughter (1st U.S. ed. ed.). New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0312155940. E-book ISBN 9781466883505

- 1 2 Appel, Jacob M. (8 November 2009). "When Infanticide Isn't Murder". The Huffington Post.

Further reading

- Twomey, Teresa (2009). Understanding Postpartum Psychosis: A Temporary Madness. Westport, CT: Praeger. ISBN 978-0-313-35346-8.