Pteropus

| Flying fox | |

|---|---|

| |

| A large flying fox (Pteropus vampyrus) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Chiroptera |

| Suborder: | Megachiroptera |

| Family: | Pteropodidae |

| Genus: | Pteropus Brisson, 1762 |

| Species | |

|

See Text | |

Bats of the genus Pteropus, belonging to the megabat suborder, Megachiroptera, are the largest bats in the world. They are commonly known as the fruit bats or flying foxes among other colloquial names. They live in the tropics and subtropics of Asia (including the Indian subcontinent), Australia, East Africa, and a number of remote oceanic islands in both the Indian and Pacific Oceans.[1] At least 60 extant species are in this genus.[2]

The oldest ancestors of the genus Pteropus to be unearthed appear in the fossil record almost exactly as they are today, the only notable differences being early flight adaptations such as a tail for stabilizing. The oldest megachiropteran is dated about 35 million years ago, but the preceding gap in the fossil record makes their true lineage unknown. Recent genetic studies, however, have supported the argument that Old World bats, such as Pteropus, share lineage with New World bats (those found in the Americas).[3][4][5][6]

Characteristically, all species of flying foxes only feed on nectar, blossoms, pollen, and fruit, which explains their limited tropical distribution. They do not possess echolocation, a feature which helps the other suborder of bats, the microbats, locate and catch prey such as insects in midair.[7] Instead, smell and eyesight are very well-developed in flying foxes. Feeding ranges can reach up to 40 miles. When it locates food, the flying fox "crashes" into foliage and grabs for it. It may also attempt to catch hold of a branch with its hind feet, then swing upside down; once attached and hanging, the fox draws food to its mouth with one of its hind feet or with the clawed thumbs at the top of its wings.

Status

Many species are threatened today with extinction, and in particular in the Pacific, a number of species have died out as a result of overharvesting for human consumption. In the Marianas, flying fox meat is considered a delicacy, which led to a large commercial trade. Human consumption of flying fox meat in Guam is hypothesized to have led to an increase of human neurodegenerative illness.[8][9] In 1989, all species of Pteropus were placed on Appendix II of CITES and at least seven on Appendix I, which restricts international trade. The subspecies P. hypomelanus maris of the Maldives is considered endangered due to limited distribution and excessive culling. The commerce in fruit bats continues either illegally or because of inadequate restrictions. Local farmers may also attack the bats because they feed in their plantations, and in some cultures, their meat is believed to cure asthma. Nonhuman predators include birds of prey, snakes, and other mammals.

The spectacled flying fox, native to Australia, is threatened by the paralysis tick, which carries paralyzing toxins.[10]

Physical characteristics

The large flying fox (P. vampyrus) is generally reported as the largest Pteropus,[1] but a few other species may match it, at least in some measurements. The large flying fox has a wingspan up to 1.5 m (4 ft 11 in) and five individuals weighed 0.65–1.1 kg (1.4–2.4 lb).[11][12] Even greater weights, up to 1.6 kg (3.5 lb) and 1.45 kg (3.2 lb), have been reported for the Indian flying fox (P. giganteus) and great flying fox (P. neohibernicus), respectively.[1][13] The black-bearded flying fox (P. melanopogon) is massive and may be heavier than all other megabats, but exact weight data are not available.[14] Comparably, no full wingspan measurements are available for the great flying fox (P. neohibernicus), but with a forearm length up to 206 mm (8.1 in),[13] it may even surpass the large flying fox (P. vampyrus) where the forearm is up to 200 mm (7.9 in).[11] Outside this genus, the giant golden-crowned flying fox (Acerodon jubatus) is the only bat with similar dimensions.[1]

Most flying fox species are considerably smaller and generally weigh less than 600 g (21 oz).[14] The smallest, the masked flying fox (P. personatus), Temminck's flying fox (P. temminckii), Guam flying fox (P. tokudae), and dwarf flying fox (P. woodfordi), all weigh less than 170 g (6.0 oz).[14]

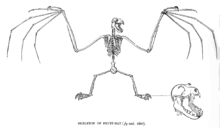

The pelage is long and silky with a dense underfur. No tail is present. As the name suggests, the head resembles that of a small fox because of the small ears and large eyes. Females have one pair of mammae located in the chest region. Ears are simple (long and pointed) with the outer margin forming an unbroken ring (a defining characteristic of megabats). The toes have sharp, curved claws.

Primate theory

Some scientists have proposed that flying foxes are descended from primates rather than bats and that mammalian flight ability has evolved more than once. This theory is not accepted by most modern zoologists and is contrary to DNA evidence.

Species

Genus Pteropus – flying foxes

- P. alecto species group

- Black flying fox, P. alecto

- Torresian flying fox, P. alecto, initially was described as separate species P. banakrisi

- Black flying fox, P. alecto

- P. caniceps species group

- Ashy-headed flying fox, P. caniceps

- P. chrysoproctus species group

- Silvery flying fox, P. argentatus

- Moluccan flying fox, P. chrysoproctus

- Makira flying fox, P. cognatus

- Banks flying fox, P. fundatus

- Solomons flying fox, P. rayneri

- Rennell flying fox, P. rennelli

- P. conspicillatus species group

- Spectacled flying fox, P. conspicillatus

- Ceram fruit bat, P. ocularis

- P. livingstonii species group

- Aru flying fox, P. aruensis

- Kei flying fox, P. keyensis

- Livingstone's fruit bat, P. livingstonii

- Black-bearded flying fox, P. melanopogon

- P. mariannus species group

- Okinawa flying fox, P. loochoensis

- Mariana fruit bat, P. mariannus

- Pelew flying fox, P. pelewensis

- Kosrae flying fox, P. ualanus

- Yap flying fox, P. yapensis

- P. melanotus species group

- Black-eared flying fox, P. melanotus

- P. molossinus species group

- Lombok flying fox, P. lombocensis

- Caroline flying fox, P. molossinus

- Rodrigues flying fox, P. rodricensis

- P. neohibernicus species group

- Great flying fox, P. neohibernicus

- P. niger species group

- Aldabra flying fox, P. aldabrensis

- Mauritian flying fox, P. niger

- Madagascan flying fox, P. rufus

- Seychelles fruit bat, P. seychellensis

- Pemba flying fox, P. voeltzkowi

- P. personatus species group

- Bismark masked flying fox, P. capistratus

- Masked flying fox, P. personatus

- Temminck's flying fox, P. temminckii

- P. poliocephalus species group

- Big-eared flying fox, P. macrotis

- Geelvink Bay flying fox, P. pohlei

- Grey-headed flying fox, P. poliocephalus

- P. pselaphon species group

- Chuuk flying fox, P. insularis

- Temotu flying fox, P. nitendiensis

- Large Palau flying fox, P. pilosus (19th century †)

- Bonin flying fox, P. pselaphon

- Guam flying fox, P. tokudae (1970s †)

- Insular flying fox, P. tonganus

- Vanikoro flying fox, P. tuberculatus (†? early 20th century)

- New Caledonia flying fox, P. vetulus

- P. samoensis species group

- Vanuatu flying fox, P. anetianus

- Samoa flying fox, P. samoensis

- P. scapulatus species group

- Gilliard's flying fox, P. gilliardorum

- Lesser flying fox, P. mahaganus

- Little red flying fox, P. scapulatus

- Dwarf flying fox, P. woodfordi

- P. subniger species group

- Admiralty flying fox, P. admiralitatum

- Dusky flying fox, P. brunneus (19th century †)

- Ryukyu flying fox, P. dasymallus

- Nicobar flying fox, P. faunulus

- Gray flying fox, P. griseus

- Ontong Java flying fox, P. howensis

- Small flying fox, P. hypomelanus

- Ornate flying fox, P. ornatus

- Little golden-mantled flying fox, P. pumilus

- Philippine gray flying fox, P. speciosus

- Small Mauritian flying fox, P. subniger (19th century †)

- P. vampyrus species group

- Indian flying fox, P. giganteus

- Andersen's flying fox, P. intermedius

- Lyle's flying fox, P. lylei

- Large flying fox, P. vampyrus

- incertae sedis

- Small Samoan flying fox, P. allenorum (19th century †)

- Large Samoan flying fox, P. coxi (19th century †)

References

- 1 2 3 4 Nowak, R. M., editor (1999). Walker's Mammals of the World. Vol. 1. 6th edition. Pp. 264-271. ISBN 0-8018-5789-9

- ↑ Simmons, N.B. (2005). "Genus Pteropus". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 334–346. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ↑ Springer, Ms; Teeling, Ec; Madsen, O; Stanhope, Mj; De, Jong, Ww (May 2001). "Integrated fossil and molecular data reconstruct bat echolocation" (Free full text). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 98 (11): 6241–6. doi:10.1073/pnas.111551998. PMC 33452

. PMID 11353869.

. PMID 11353869. - ↑ "Primitive Early Eocene bat from Wyoming and the evolution of flight and echolocation". Nature. 2008-02-14. doi:10.1038/nature06549. Retrieved 2008-07-03.

- ↑ Teeling, Ec; Springer, Ms; Madsen, O; Bates, P; O'Brien, Sj; Murphy, Wj (January 2005). "A molecular phylogeny for bats illuminates biogeography and the fossil record". Science. 307 (5709): 580–4. doi:10.1126/science.1105113. PMID 15681385.

- ↑ Eick, Gn; Jacobs, Ds; Matthee, Ca (September 2005). "A nuclear DNA phylogenetic perspective on the evolution of echolocation and historical biogeography of extant bats (chiroptera)" (Free full text). Molecular Biology and Evolution. 22 (9): 1869–86. doi:10.1093/molbev/msi180. PMID 15930153.

- ↑ Matti Airas. "Echolocation in bats" (PDF). HUT, Laboratory of Acoustics and Audio Signal Processing. p. 4. Retrieved July 19, 2013.

- ↑ Cox, P. , Davis, D., Mash, D. , Metcalf J.S., Banack, S. A. (2016). "Dietary exposure to an environmental toxin triggers neurofibrillary tangles and amyloid deposits in the brain". Proc. Royal Society, B. 238 (3): 1–10. doi:10.1098/rspb.2015.2397.

- ↑ Holtcamp, W. (2012). "The emerging science of BMAA: do cyanobacteria contribute to neurodegenerative disease?". Environmental Health Perspectives. 120 (1823): a110–a116. doi:10.1289/ehp.120-a110. PMC 3295368

. PMID 22382274.

. PMID 22382274. - ↑ Mueller, R. 2000. "Pteropus conspicillatus" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed May 03, 2007 at

- 1 2 Francis, C. M. (2008). Mammals of Southeast Asia. Pp. 195-196. ISBN 978-0-691-13551-9

- ↑ Payne, J., and Francis, C. M. (1998). Mammals of Borneo. P. 172. ISBN 967-99947-1-6

- 1 2 Flannery, T. (1995). Mammals of New Guinea. Pp. 376-377. ISBN 0-7301-0411-7

- 1 2 3 Flannery, T. (1995). Mammals of the South-West Pacific & Moluccan Islands. Pp. 245-303. ISBN 0-7301-0417-6

Further reading

- Altringham, J.D. (1996). Bats: biology and behaviour. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-850322-9.

- Hall, L. S. & Richards, G. C. (2000). Flying foxes: fruit and blossom bats of Australia. Sydney: University of New South Wales Press. ISBN 0-86840-561-2.

- Marshall, A.G. (1985). "Old world phytophagus bats (Megachiroptera) and their food plants: a survey". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 83 (4): 351–369. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1985.tb01181.x.

- Mickleburgh, S., Hutson, A.M. & Racey, P. (1992) Old World Fruit Bats: An Action Plan for Their Conservation. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN

- Musser, Guy G.; Koopman, Karl F.; Califia, Debra (1982). "The Sulawesian Pteropus arquatus and P. argentatus Are Acerodon celebensis; The Philippine P. leucotis Is an Acerodon". Journal of Mammalogy. 63 (2): 319–328.

- Neuweiler, G. (2000). The Biology of Bats. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-509951-6.

- Nowak, R.M. & Walker, E.P. (1994). Walker's bats of the world. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-4986-1.

- Welbergen, J.; Klose, S.; Markus, N.; Eby, P. (2008). "Climate change and the effects of temperature extremes on Australian flying-foxes". Proceedings. Biological sciences / the Royal Society. 275 (1633): 419–425. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.1385. PMC 2596826

. PMID 18048286.

. PMID 18048286. - Klose, S. M. (2006). "The flying fox manual. A new handbook for wildlife carers in Australia". Acta Chiropterologica. 8 (2): 573–572. doi:10.3161/1733-5329(2006)8[573:BR]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 1733-5329.

- Vardon, M.J. & Tidemann, C.R. (1995) Harvesting of flyingfoxes (Pteropus spp.) in Australia: could it promote the conservation of endangered Pacific island species? In Conservation through sustainable use of wildlife (eds G. Grigg, P. Hale & D. Lunney), pp. 82–85, Brisbane, Australia.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to: Pteropus |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pteropus. |

- Flying Fox Manual – A manual for Wildlife Carers in Australia by Dave Pinson

-

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Flying-fox". Encyclopædia Britannica. 10 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 586.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Flying-fox". Encyclopædia Britannica. 10 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 586.