Private Eye

|

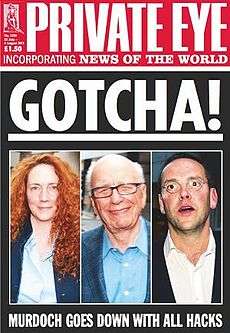

A July 2011 cover following the closure of the News of the World, making ironic use of a famous 1982 headline from sister paper The Sun | |

| Editor | Ian Hislop |

|---|---|

| Categories | Satirical news magazine |

| Frequency | Fortnightly |

| Circulation |

230,099 (January–June 2016)[1] |

| Year founded | 1961 |

| Company | Pressdram Ltd |

| Based in |

London, W1 United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Website | private-eye.co.uk |

| ISSN | 0032-888X |

Private Eye is a British fortnightly satirical and current affairs news magazine, founded in 1961. It is published in London and has been edited by Ian Hislop since 1986.

The publication is widely recognised for its prominent criticism and lampooning of public figures such as politicians and media tycoons, and of organisations that it considers incompetent, inefficient, corrupt, pompous or self-important; it has established itself as a thorn in the side of the British establishment. It is also known for its in-depth investigative journalism into under-reported scandals and cover-ups.

Private Eye is Britain's best-selling current affairs magazine,[2] and such is its long-term popularity and impact that many of its recurring in-jokes have entered popular culture.

History

The forerunner of Private Eye was a school magazine, The Salopian, published at Shrewsbury School in the mid-1950s and edited by Richard Ingrams, Willie Rushton, Christopher Booker and Paul Foot. After National Service, Ingrams and Foot went as undergraduates to Oxford University, where they met their future collaborators Peter Usborne, Andrew Osmond,[3] John Wells and Danae Brook, among others.

The magazine proper began when Usborne learned of a new printing process, photo-litho offset, which meant that anybody with a typewriter and Letraset could produce a magazine. The publication was initially funded by Osmond and launched in 1961. It was named when Osmond looked for ideas in the well-known recruiting poster of Lord Kitchener (an image of Kitchener pointing with the caption "Wants You") and, in particular, the pointing finger. After the name Finger was rejected, Osmond suggested Private Eye, in the sense of someone who "fingers" a suspect. The magazine was initially edited by Booker and designed by Rushton, who drew cartoons for it. Its subsequent editor, Ingrams, who was then pursuing a career as an actor, shared the editorship with Booker, from around issue number 10, and took over from issue 40. At first, Private Eye was a vehicle for juvenile jokes: an extension of the original school magazine, and an alternative to Punch. However, according to Booker, it got "caught up in the rage for satire".

After the magazine's initial success, more funding was provided by Nicholas Luard and Peter Cook, who ran The Establishment – a satirical nightclub – and Private Eye became a fully professional publication.

Others essential to the development of the magazine were Auberon Waugh, Claud Cockburn (who had run a pre-war scandal sheet, The Week), Barry Fantoni, Gerald Scarfe, Tony Rushton, Patrick Marnham and Candida Betjeman. Christopher Logue was another long-time contributor, providing the column "True Stories", featuring cuttings from the national press. The gossip columnist Nigel Dempster wrote extensively for the magazine before he fell out with Ian Hislop and other writers, while Foot wrote on politics, local government and corruption.

Ingrams continued as editor until 1986, when he was succeeded by Hislop. Ingrams remains chairman of the holding company.[4]

Style of the magazine

Private Eye often reports on the misdeeds of powerful and important individuals and, consequently, has received numerous libel writs throughout its history. These include three issued by James Goldsmith (known in the magazine as "(Sir) Jammy Fishpaste") and several by Robert Maxwell (known as "Captain Bob"), one of which resulted in the award of costs and reported damages of £225,000, and attacks on the magazine by Maxwell through a book, Malice in Wonderland, and a one-off magazine, Not Private Eye.[5] Its defenders point out that it often carries news that the mainstream press will not print for fear of legal reprisals or because the material is of minority interest.

As well as covering a wide range of current affairs, Private Eye is also known for highlighting the errors and hypocritical behaviour of newspapers in the "Street of Shame" column. It reports on parliamentary and national political issues, with regional and local politics covered in equal depth under the "Rotten Boroughs" column. Extensive investigative journalism is published under the "In the Back" section, often tackling cover-ups and unreported scandals. A financial column called "In the City", written by Michael Gillard under the pseudonym "Slicker", has generated a wide business readership as a number of significant financial scandals and unethical business practices and personalities have been exposed there.

Some contributors to Private Eye are media figures or specialists in their field who write anonymously, often under humourous pseudonyms, such as "Dr B Ching" who writes the "Signal Failures" column about the railways, in reference to the Beeching cuts. Stories sometimes originate from writers for more mainstream publications who cannot get their stories published by their main employers.

Private Eye has traditionally lagged behind other magazines in adopting new typesetting and printing technologies. At the start it was laid out with scissors and paste and typed on three IBM Executive typewriters – italics, pica and elite – lending an amateurish look to the pages. For some years after layout tools became available the magazine retained this technique to maintain its look, although the three older typewriters were replaced with an IBM composer. Today the magazine is still predominantly in black and white (though the cover and some cartoons inside appear in colour) and there is more text and less white space than is typical for a modern magazine. Much of the text is printed in the standard Times New Roman font. The former "Colour Section" was printed in black and white like the rest of the magazine: only the content was colourful.

Frequent targets for parody and satire

While the magazine in general reports corruption, self-interest and incompetence in a broad range of industries and lines of work, certain people and entities have received a greater amount of attention and coverage in its pages. As the most visible public figures, prime ministers and senior politicians make the most natural targets, but Private Eye also aims its criticism at journalists, newspapers and prominent or interesting businesspeople. It is the habit of the magazine to attach nicknames, usually offensive or crude, to these people, and often to create surreal and extensive alternate personifications of them, which usually take the form of parody newspaper articles in the second half of the magazine.

Frequent and notable investigations

Private Eye has regularly and extensively reported on and investigated a wide range of far-reaching issues, including:

- The utilisation of tax havens by large corporations and the failure of government in tackling the problem.

- The revolving door from politics to lucrative corporate roles.

- The MPs' expenses scandal and ongoing abuses of the expenses system.

- Conflicts of interest in general, but particularly between public officials or politicians and big business, the arms trade, etc.

- Human rights abuses by countries with whom the government continues to carry on business.

- Phone hacking and other improper practices in the mainstream press.

- The deaths at Deepcut army barracks between 1995 and 2002, particularly that of Cheryl James in 1995.

- The investigation into the Lockerbie bombing of 1988.

- The contaminated blood scandal of the 1970s and 1980s.

Regular sections

Regular columns

The opening page of each edition is usually dedicated to the bigger stories of the fortnight. The larger key regular sections include:

- "News" (previously called "The Colour Section") – following the opening page, this section contains additional major stories worthy of note.

- "Street of Shame" – covering newspapers, journalists and other media groups, and usually largely written by Francis Wheen and Adam Macqueen. The title refers to Fleet Street, where many of the British papers were once based.

- "HP Sauce" – covering national politics and politicians. "HP" refers to the Houses of Parliament, as well as being an actual brand of sauce.

- "Called to Ordure" – reporting on recent parliamentary skirmishes or notable select committee appearances by regulators or senior civil servants, written by the pseudonymous "Gavel Basher".

- "Rotten Boroughs" – reporting on dubious practices, absurdity and corruption in local government. The name is a play on the term rotten borough. This section, edited by Tim Minogue, receives scores of tips and leads from councillors, whistleblowing council officials, freelance journalists and members of the public.

- "In The Back" – in-depth investigative journalism, often taking the side of the downtrodden. This section was overseen by Paul Foot until his death in 2004; under his tenure it was known as "Footnotes". It often features stories on potential miscarriages of justice and stories on other embarrassing establishment misdeeds.

- "In The City" – analysis of financial and business affairs.

Other regular columns with more specialised interest include:

- "Ad Nauseam" – the excesses, plagiarism and creative failings of the advertising industry.

- "The Agri Brigade" – covering agricultural issues and rural affairs, written by "Bio-Waste Spreader".

- "Brussels Sprouts" – the foibles of the European Union and its parliament.

- "Eye TV" – analysis of recent television programmes, with news and criticism of the UK televised media, written by the pseudonymous "Remote Controller". (ITV is a British television channel.)

- "Keeping the Lights On" – reporting on the issues facing the energy industry, written by "Old Sparky".

- "Medicine Balls" – issues in healthcare, often with specific interest in the National Health Service, written by the general practitioner (and sometime comedian) Phil Hammond under the pseudonym "MD".

- "Letter From..." – column purporting to be written by a resident of a particular city or country highlighting its current political or social situation. The name derives from Alistair Cooke's Letter from America. It is often accompanied by a smaller report from elsewhere in the world, under a heading such as "Postcard From...", "Dispatch From..." or "Communique From...".

- "Literary Review" – book reviews and news from the world of publishing and bookselling, written by the pseudonymous "Bookworm". The masthead from the magazine of the same name, formerly edited by Auberon Waugh (aka Abraham Wargs, "The Voice of Himself"), is lifted for this section. Regular sections include a critical review; "What You Didn't Miss", a pastiche summary of a recent book; "Books & Bookmen", articles about the absurdities of the publishing business (its title taken from a now-defunct British magazine); and "Library News". The column produces an annual summary of "logrolling", the activity whereby literary colleagues publish favourable reviews of each other's books, or where rivals have disparaged their competitors' publications.

- "Man/Woman in the Eye" – usually detailing the past exploits of a new member of parliament or someone recently appointed into a government advisory role and why these exploits make their appointment inappropriate.

- "Music and Musicians" – reports on the artistic and political intrigues behind the scenes in the world of classical music. Written by "Lunchtime O'Boulez", who has been a resident Private Eye journalist since the magazine's earliest days; Pierre Boulez, French avant garde composer and conductor, was a controversial choice as principal conductor of the BBC Symphony Orchestra in the early 1970s. In an earlier incarnation, the column published scurrilous and unfounded gossip about the London Symphony Orchestra, which resulted in a significant libel payout.[6] The title of the column is taken from a now-defunct British magazine which was a sister publication of Books & Bookmen.

- "Nooks and Corners" – architectural news and criticism. This is one of the magazine's best-known sections. It was originally titled "Nooks & Corners of the New Barbarism", a reference to the architectural movement known as New Brutalism. The column was founded by John Betjeman and is today written by architectural historian Gavin Stamp using the name "Piloti".

- "Pseuds Corner" – listing pompous and pretentious quotations from the media. At various times different columnists have been regular entrants, with varied reactions. At one point in the 1970s, Pamela Vandyke Price, a Sunday Times wine columnist, wrote to the magazine complaining that "every time I describe a wine as anything other than red or white, dry or wet, I wind up in Pseud's Corner". In about 1970, the editor of the Radio Times, Geoffrey Cannon, regularly appeared because of his habit of using "hippie" argot out of context in an attempt to appear "with it" and trendy. Simon Barnes, a sports writer for The Times, has been regularly quoted in the column for many years. The column now often includes a sub-section called Pseuds Corporate, which prints unnecessarily prolix extracts from corporate press releases and statements.

- "Signal Failures" – covering news and issues with regards to the railways. The author's pseudonym, "Dr B Ching", refers to Richard Beeching, whose report into the rail network led to widespread cuts to it in the 1960s.

- "Squarebasher" – looking at matters relating to all of the armed forces, including deployments, equipment and training.

The magazine also features periodic columns such as "Library News", "Libel News", "Charity News" and others, detailing recent happenings in those areas. These follow predictable formats: library news usually chronicles local councils' bids to close libraries; libel news highlights what it considers unjust libel judgements; while charity news usually questions the financial propriety of particular charities. "Poetry Corner" is the periodic contribution of obituaries by the fictional junior poet "E. J. Thribb". "St Cake's School" is an imaginary public school, run by Mr R. J. Kipling (BA, Leicester), which posts a diary of highly unlikely and arcane-sounding termly activities.

Satirical and entertaining columns

- "Commentatorballs", previously known as Colemanballs – verbal gaffes from broadcasting. Previously named after the former BBC broadcaster David Coleman, who was adjudged particularly prone to such solecisms during his many sporting commentaries. Variants also appear in which publications and press releases are mocked for inappropriately latching onto a current fad to draw unwarranted attention to something else, such as "Dianaballs" (following Princess Diana's death in 1997), "Millenniumballs" (1999), "Warballs" (following the September 11 attacks), "Tsunamiballs" (following the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake), "Obamaballs" (after the election of U.S. President Barack Obama in 2008), and "Electionballs" following any election.

- "Court Circular" – a parody of The Daily Telegraph and The Times Court Circular sections which detail the activities of the Royal Family.

- "Curse of Gnome" – an irregular column in which targets of Private Eye who have responded in kind are mocked when they suffer a misfortune. "Gnome" refers to the magazine's supposed proprietor, Lord Gnome.

- "Diary" – a parody of a weekly column which appears in The Spectator, written by Craig Brown in the style of the chosen celebrity. One of the few regular columns with a byline, which was introduced after Alan Clark sued Peter Bradshaw, then of the London Evening Standard, for his unattributed parody of Clark's diaries.

- "Funny Old World" – supposedly genuine quirky news stories from around the world, and one of the few columns with a byline, compiled by Victor Lewis-Smith. Continued an earlier column, Christopher Logue's "True Stories".

- "National Treasures" – extracts from the media praising individuals and invariably using the expression "national treasure".

Newspaper parodies

Part of the latter half of the magazine is taken up with parodies of newspapers, spoofing various publications' layouts, writing styles and adverts. Where further content is implied, but omitted, this is said to continue "on page 94".

- "A Doctor Writes" – the fictional "A. Doctor" or "Dr Thomas Utterfraud" parodies newspaper articles on topical medical conditions, particularly those by Dr Thomas Stuttaford.

- "A Taxi Driver Writes" – a view from a purported taxi driver, usually a politician or media personality, who will be named as (for example) No. 13458 J Prescott. The column gives excessively one-sided views, usually of a right-wing nature (playing on the stereotype of black cab drivers as right-wing populists with bigoted views), saying that a named group or individual should be "strung up" (hanged).

- "Dave Spart" – ultra-left wing activist, always representing a ridiculous-sounding union (such as the National Amalgamated Union of Sixth-Form Operatives and Allied Trades), collective or magazine, which is frequently based in Neasden. Spart's views attempt to highlight alleged misconduct, prejudice or general wrongdoing, but are contradictory and illogical. The name Spart is derived from the German Spartacus League that existed during World War I, and other subsequent revolutionary groups.

- "Glenda Slagg" – brash, libidinous and self-contradictory female reporter (and former "First Lady of Fleet Street") based on Jean Rook and Lynda Lee-Potter. Every sentence from Slagg ends with an onslaught of punctuation made up of repeated "?" and "!" signs, and often features intermittent editorial commentary such as "you've done this already, get on with it" or, ultimately, "you're fired". Frequently the first paragraph of her column will start with the name of a celebrity followed by "Don'tchaluvim?", the next with the same celebrity name and "Ain'tyasickofim?". Her last paragraph frequently features a celebrity with an unusual name, and the dubious claim "Crazy name, crazy guy!?!"

- "From The Messageboards" – a spoof of Internet forums.

- "Gnomemart" – the Christmas special edition of Private Eye includes spoof adverts for expensive but useless mail-order gadgets, usually endorsed by topical celebrities and capable of playing topical songs or TV theme tunes.

- "Lunchtime O'Booze" has been among the magazine's resident journalists since the early days. The name is a comment on journalists' supposed traditional fondness for alcohol, their prandial habits, and the suspicion that they pick up many of their stories in public houses. (The name was notably to be used by Auberon Waugh to describe fellow Spectator journalist George Gale, with Waugh being sacked as a result).

- "Mary Ann Bighead" – a mockery of the former Times columnist and assistant editor Mary Ann Sieghart. Bighead is lampooned for her pretentions, ignorance, boastfulness about her children Brainella and Intelligencia, high standard of living, travels (mainly to developing countries where she patronises the locals), and the fact that she can speak so many languages (including Swahili, Tagalog and 13th Century Mongolian).

- "Me and my Spoons" – a spoof interview of a noted person, in the style of a Sunday supplement regular feature, in which the subject is asked about their putative collection of spoons. The style of the replies, allegedly reflecting the personal style of the interviewee, is more important than the content. The article typically ends with a hint that the next interview will be with someone whose name might bring an amusing twist to the series, such as "Next week: Ed Balls – Me and my Balls".

- "Neasden United FC", playing in the "North Circular Relegation League", is a fictional football club from Neasden, north London, often used to satirise English football in general with the manager "ashen-faced supremo Ron Knee, 59" possibly from Ron Atkinson, and their only two fans "Sid and Doris Bonkers", playing on the idea of tiny devoted fanbases of unsuccessful football clubs. "Baldy" Pevsner (a reference to German born writer Nikolaus Pevsner), praised by The Guardian as one of Knee's "two greatest signings",[7] has been credited with scoring yet another own goal in every issue of the magazine, in addition to the occasional "one boot". Some of the credit for Pevsner's achievement must also go to Knee's other "greatest signing ... the ever-present one-legged goal keeper Wally Foot".[7]

- "Obvious headline" – banal stories about celebrities that receive extensive reporting in the national press are rewritten as anonymous headlines, such as "SHOCK NEWS: MAN HAS SEX WITH SECRETARY". This is usually "EXCLUSIVE TO ALL NEWSPAPERS". This is often followed by slightly oblique, "shocking" references to the Pope being Catholic, and to bears defecating in the woods.

- "Official Apology" or "Product Recall" – spoofs the official apologies and product recall notices that newspapers are mandated to print. For example, the subject might be the English national football team. Always starts "In common with all other newspapers" (or retailers), implying that none has apologised.

- "Poetry Corner" – trite obituaries of the recently deceased in the form of poems from the fictional teenage poet E. J. Thribb (17½). The poems usually bear the heading "In Memoriam..." and begin "So. Farewell then...".

- "Polly Filler" – a vapid and self-centred female "lifestyle" columnist, whose irrelevant personal escapades and gossip serve solely to fill column inches. She complains about the workload of the modern woman whilst passing all parental responsibility onto "the au pair", who always comes from a less-advanced country, is paid a pittance, and fails to understand the workings of some mundane aspect of "lifestyle" life. Her name is derived from Polyfilla, a DIY product used to fill holes and cracks in plaster. Polly's sister Penny Dreadful makes an occasional appearance. Like several Private Eye regulars, Polly is based on more than one female columnist, but Jane Moore of The Sun, whose remarks are often echoed by Polly or commented on elsewhere in the magazine, is a major source. Additionally, the column mocks Rupert Murdoch's media empire in general and Sky television in particular, as Polly's husband, "the useless Simon", is usually mentioned as being in front of the television (wasting time) watching exotic sports on obscure satellite television channels.

- "Police Log – Neasden Central Police Station" – a fictional police station log, satirising current police policies that are met with general contempt and/or disdain. Ordinary police activities are ignored, with police attention limited to "counter-terrorism", obsessive political correctness and pointless bureaucracy. For example, one incident reports on an elderly woman being attacked by a gang of youths, arrested (and unfortunately dying of "natural causes" in police custody) for infringing their right to terrorise pensioners.

- "Pop Scene by Maureen Cleavage" – originally a spoof of press coverage of the music business and in particular Maureen Cleave, who had a column in the Evening Standard. In the early to mid-1960s, popular culture was starting to be taken more seriously by the heavier newspapers; some claim that Private Eye considered this approach pretentious and ripe for ridicule, although others argue that the magazine was in fact covering popular culture before some of the more serious newspapers. This section also provided an outlet for satirical comment on popular musicians, whose antics were usually attributed to the fictional pop group "The Turds" and their charismatic leader "Spiggy Topes". Topes and the Turds were originally based on The Beatles and a thinly disguised John Lennon, but the names were eventually applied to any rock star or band whose excesses featured in the popular press. (Although at the same time there was a real group called The Thyrds who appeared in the final of ITV's Ready, Steady, Win! competition.)

- "Sally Jockstrap" – a fictional sports columnist who is incapable of correctly reporting any sporting facts. Her articles are usually a mishmash of references to several sports, along the lines of "there was drama at Twickenham as Michael Schumacher double faulted to give Arsenal victory". Said to be inspired by Lynne Truss.[8]

- "Toy-town News" or "Nursery Times" – a newspaper based on the mythology of children's stories. For example, the royal butler Paul Burrell was satirised as the "Knave of Hearts" who was "lent" tarts "for safe keeping", rather than stealing them as in the rhyme. Nigel Dempster is referred to as "Humpty Dumpster".

- "Ye Daily Tudorgraph" – a newspaper written in mock Tudor period language, set in that time and clearly a parody of the Daily Telegraph. It usually suggests that former Telegraph editor Bill Deedes was a young boy at the time.

Prime Minister parodies

A traditional fixture in Private Eye is a full-page parody of the Prime Minister of the day. The style is chosen to mock the perceived foibles and folly of each Prime Minister:

- Harold Wilson, who cultivated an exaggerated working class image, was mocked in "Mrs Wilson's Diary", supposedly written by his wife, Mary Wilson. This parodied Mrs Dale's Diary, a popular BBC radio series.

- Edward Heath, who was labelled "The Grocer", and whose government was beset by economic and political problems, presided over Heathco, permanently "going out of business".

- As leader of the opposition to Margaret Thatcher, Neil Kinnock was shown as "Dan Dire" (based on the comic-strip character Dan Dare), in his struggle against the Maggon, "Supreme Ruler of the Universe".

- John Major, undermined and embarrassed by his party's right wing during the 1990s, vented his frustrations in "The Secret Diary of John Major", inspired by the Sue Townsend "Adrian Mole" books.

- Tony Blair was portrayed as the sanctimonious Vicar of St. Albion's, a fictional parish church, in "St. Albion's Parish News". Editor Ian Hislop has said the idea came about after Blair walked into Downing Street carrying his guitar in 1997, like "the new vicar [about] to sing Kumbaya." Richard Ingrams wrote in The Observer that he was amused to see the parody become true, after Blair left office and formed the Faith Foundation to promote religious harmony.

- During his premiership from 2007 to 2010, Gordon Brown was mocked as the Supreme Leader of a North Korean-style state, railing against the "running dog ex-Comrade Blair" and secret plots to depose him. This enabled Private Eye to comment on Brown's lack of election as Prime Minister, either by the public or the Labour Party, as well as his supposed Stalinist style of leadership.

- When the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats formed a coalition government in 2010, the column became "Downturn Abbey" – taking its name from the drama Downton Abbey.

- Later, the column became the newsletter of the fictional "New Coalition Academy (formerly Brown's Comprehensive)", in which Prime Minister David Cameron and Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg were portrayed as headmaster and deputy headmaster. The motto of the Academy was "Duo in Uno". In theory, both leaders wrote a column in each issue, but in practice, Clegg's contributions were frequently "held over due to lack of space".

- Following the 2015 general election and the exit of the Liberal Democrats from government, the newsletter continued in a similar form as "The Cameron Free School (formerly Coalition Academy), sole Headmaster David Cameron MA (Oxon)".

- Since the appointment of Theresa May as Prime Minister in 2016, the school newsletter format has continued under the title "St. Theresa's Independent State Grammar School for Girls (and Boys)".

Not all of Private Eye's parodies have been unsympathetic. During the 1980s, Ingrams and John Wells wrote fictional letters from Denis Thatcher to Bill Deedes in the Dear Bill column, mocking Thatcher as an amiable, golf-playing drunk. The column was collected in a series of books and became a play in which Wells played the fictional Denis, a character now inextricably "blurred [with] the real historical figure", according to Ingrams.[9]

Mini-sections

Private Eye also contains a variety of regular mini-sections, consisting of small amusing examples of different aspects of everyday life, generally sent in by readers. They include "Dumb Britain" (examples of ignorance observed on quiz shows), "Order of the Brown Nose" (an example of over-zealous praise of another individual), and "Let's Parlez Franglais" (which mocks recent political events, mainly within Europe, by creating an imaginary transcript in Franglais, usually ending with a reference to 'Kilometres' Kington).

Miscellaneous

- "Classified" – adverts from readers. In the past, these commonly featured personal ads that used code words to describe particular sexual acts. Currently, the adverts usually include products for sale, conspiracy theorists promoting their ideas, and the "Eye Need" adverts in which people request money for personal causes.

- "Crossword" – a cryptic prize crossword, notable for its vulgarity. In the early 1970s the crossword was set by the Labour MP Tom Driberg, under the pseudonym "Tiresias" (supposedly "a distinguished academic churchman"). As of 2011 it is set by one of The Guardian's cryptic crossword setters, Eddie James ("Brummie" in the paper) under the name "Cyclops". The crossword frequently contains offensive language and references (both in the clues and the solutions), and a knowledge of the magazine's in-jokes and slang is necessary to solve it.

- "Letters" – although consisting mostly of readers' letters, this section frequently includes letters from high-profile figures, sometimes in order for the magazine to print an apology or avoid litigation. Other letters express distaste at a recent article or cartoon, many ending by saying (sometimes in jest) that they will (or will not) cancel their subscription. This section also prints celebrity "Lookalikes" and the "Pedantry Corner" features letters from readers correcting minor mistakes.

- "The Book of..." – a spoof of the Old Testament, applying language and imagery reminiscent of the King James Bible to current affairs in the Middle East.

- "The Alternative Rocky Horror Prayer Book" – a pastiche of attempts to update Anglican religious ceremonies into more modern versions.

- "Sylvie Krin" – (in allusion to the shampoo brand Silvikrin) the alleged author of pastiche romantic fiction in the style of Barbara Cartland, with names like Heir of Sorrows (about Prince Charles) and Never Too Old (about Rupert Murdoch).

Former sections

- "Auberon Waugh's Diary" – Waugh wrote a regular diary for the magazine, usually combining real events from his own life with fictional episodes such as parties with Queen Elizabeth II, from the early 1970s until 1985. It was generally written in the persona of an ultra-right-wing country gentleman, a subtle exaggeration of his own personality. He described it as the world's first example of journalism specifically dedicated to telling lies.

- "Down on the Fishfarm" – issues relating to fish farming. Subsequently expanded to cover various environmental issues and renamed "Eco-Gnomics", after several alternative titles were tried out. Now absorbed into "The Agri Brigade" section.

- "London Calling" – a round-up of news, especially of the "loony left" variety, during the days of the Greater London Council. This column was retired when the GLC was abolished.

- "Sally Deedes" – genuine consumer journalism column, exposing corrupt or improper goods, services or dealings. This column was the origin of the magazine's first-ever libel victory in the mid-1990s.

- "Illustrated London News" – a digest of news and scandal from the city, parodying (and using the masthead of) the defunct gazette of the same name. It was usually written by the radical pioneer journalist Claud Cockburn.

- "Grovel" – a "society" column, featuring gossip, scandal and scuttlebutt about the rich and famous, and probably the section that gave rise to the magazine's largest number of libel claims. Its character and style (accompanied by a drawing of a drunk man with a monocle, top hat and cigarette holder) was based on Nigel Dempster, lampooned as Nigel Pratt-Dumpster. Grovel last appeared in issue 832 in November 1993.

- "Hallo!" – the "heart-warming column" purportedly written by The Marquesa, was nearly identical to Grovel in content, but with a new prose style parodying the breathless and gushing format established by magazines such as Hello.

- "High Principals" – examined further and higher education issues and spotlighting individuals who might have acted in their own interests, rather than those of education. These stories are now often found under "Rotten Boroughs" and "In the Back".

- "Levelling the Playing Fields" – chronicled what the magazine saw as the public sector's bid to sell off as much of its remaining recreational green space as possible to supermarkets or housing developers.

- "That Honorary Citation in Full" – a Dog Latin tribute to prominent figures awarded honorary degrees, usually beginning "SALUTAMUS".[10]

- "Thomas, The Privatised Tank Engine" – a parody of Rev. W. Awdry's Railway Series, written by Incledon Clark and printed at the time of the debate over the privatisation of British Rail in 1993-94.

- "Under The Microscope" – looked at matters and issues affecting the science community.

- "Wimmin" – a regular 1980s section featuring quotes from feminist writing deemed to be ridiculous (similar to today's "Pseuds Corner").

Special editions

The magazine has occasionally published special editions dedicated to the reporting of particular events, such as government inadequacy over the 2001 foot and mouth outbreak, the conviction in 2001 of Abdelbaset al-Megrahi for the 1988 Lockerbie bombing (an incident regularly covered since by "In the Back"), and the MMR vaccine controversy in 2002.

A special issue was published in 2004 to mark the death of long-time contributor Paul Foot. In 2005, The Guardian and Private Eye established the Paul Foot Award (referred to colloquially as the "Footy"), with an annual £10,000 prize fund, for investigative/campaigning journalism in memory of Foot.[11]

Recurring in-jokes

The magazine has a number of recurring in-jokes and convoluted references, often comprehensible only to those who have read the magazine for many years. They include references to controversies or legal ambiguities in a subtle euphemistic code, such as replacing the word "drunk" with "tired and emotional", or using the phrase "Ugandan discussions" to denote illicit sexual exploits; and more obvious parodies utilising easily recognisable stereotypes, such as the lampooning as "Sir Bufton Tufton" of Conservative MPs viewed to be particularly old-fashioned and intellectually lazy. Such terms have sometimes fallen into disuse as their hidden meanings have become better-known.

The magazine often deliberately misspells the names of certain organisations, such as "Crapita" for the outsourcing company Capita, "Carter-Fuck" for the law firm Carter-Ruck, and "The Grauniad" for The Guardian. Certain individuals may be referred to by another name, for example Piers Morgan as "Piers Moron", Richard Branson as "Beardie", Rupert Murdoch as the "Dirty Digger", and Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Charles as "Brenda" and "Brian".

The first half of each issue of the magazine, which consists chiefly of news reporting and investigative journalism, tends to include these in-jokes in a more subtle manner, so as to maintain journalistic integrity, while the second half, generally characterised by unrestrained parody and cutting humour, tends to present itself in a more confrontational way.

Cartoons

As well as many one-off cartoons, Private Eye features a number of regular comic strips:

- Apparently by Mike Barfield – satirising day-to-day life or pop trends.

- Celeb by Charles Peattie and Mark Warren, collectively known as Ligger – a strip about a celebrity rock star named Gary Bloke, which first appeared in 1987. A BBC sitcom version was spun-off in 2002.[12]

- Desperate Business – stereotypes a range of professions, such as an estate agent showing a couple a minuscule house, with the caption: "It's a bit smaller than it looked on your website".

- EUphemisms by RGJ – features a European Union bureaucrat making a statement, with a caption suggesting what it means in real terms, generally depicting the EU in a negative or hypocritical light. For example, an EU official declares: "Punishing Britain for Brexit would show the world we've lost the plot", with the caption reading: "We're going to punish Britain for Brexit. We've lost the plot".

- Fallen Angels – a regular cartoon with a caption depicting problems (often bureaucratic) in the National Health Service.

- Forgotten Moments in Music History – features cryptic references to notable songs and artists.

- Gogglebollox by Goddard – a satirical take on recent television shows.

- It's Grim Up North London by Knife and Packer – satire about Islington "trendies" which has featured since 1999.

- The Premiersh*ts by Paul Wood – satire of professional football and footballers, in particular in the Premier League.

- Scenes You Seldom See by Barry Fantoni – satirising the habits of British people by portraying the opposite of what is the generally accepted norm.

- Snipcock & Tweed by Nick Newman – about two book publishers.

- Supermodels by Neil Kerber – satirising the lifestyle of supermodels; the characters are unfeasibly thin.

- Yobs and Yobettes by Tony Husband – satirising yob culture, featuring since the late-1980s.

- Young British Artists by Birch – a spoof of the Young British Artists movement such as Tracey Emin and Damien Hirst.

Some of the magazine's former cartoon strips include:

- The Adventures of Mr Millibean – former Leader of the Opposition, Ed Miliband, is portrayed as Rowan Atkinson's Mr Bean.

- Andy Capp-in-Ring – a parody of Andy Capp, satirising Labour leadership candidate Andy Burnham and his rivals, portraying Burnham as Capp.

- Barry McKenzie – a popular strip in the mid-1960s detailing the adventures of an expatriate Australian in Earl's Court, London and elsewhere, written by Barry Humphries and drawn by Nicholas Garland.

- Battle for Britain – a satire of British politics (1983–87) in terms of a World War II war comic.

- The Broon-ites – a pastiche of Scottish cartoon strip The Broons, featuring Gordon Brown and his close associates. The speech bubbles are written in broad Scots.

- Dan Dire, Pilot of the Future? and Tony Blair, Pilot for the Foreseeable Future – parodies of the Dan Dare comics of the 1950s, satirising (respectively) Neil Kinnock's time as Labour leader, and Tony Blair's Labour government.

- Dave Snooty and his New Pals – drawn in the style of The Beano, it parodied David Cameron as "Dave Snooty" (a reference to the Beano character "Lord Snooty"), involved in public schoolboy-type behaviour with members of his cabinet. Cameron is portrayed as wearing an Eton College uniform with bow tie, tailcoat, waistcoat and pinstriped trousers.

- The Directors by Dredge & Rigg – commented on the excesses of boardroom fat cats.

- The Cloggies by Bill Tidy – about clog dancers.

- The Commuters by Grizelda – followed the efforts of two commuters to get a train to work.

- Global Warming: The Plus Side – a satire of the effects of global warming, suggesting mock "positive" impacts of the phenomena, such as bus-sized marrows in village vegetable competitions, vastly decreased fossil prices due to melting permafrost, and the proliferation of British citrus orchards.

- Great Bores of Today by Michael Heath.

- The Has-Beano – a pastiche of The Beano used to satirise The Spectator and Boris Johnson (who features as the lead character, Boris the Menace).

- Hom Sap by David Austin.

- Liz – a cartoon about the Royal Family drawn by Cutter Perkins and RGJ in the style of the comic magazine Viz (with speech in Geordie dialect). Ran from issue 801 to 833.

- Meet the Clintstones – The Prehistoric First Family – drawn in the style of The Flintstones, this was a parody of Bill and Hillary Clinton during his presidency and the 2008 U.S. presidential election.

- Off Your Trolley by Reeve & Way – set in an NHS hospital.

- The Regulars also by Heath – based on the drinking scene at the Coach and Horses pub in London (a regular meeting place for the magazine's staff and guests), and featuring the catchphrase "Jeff bin in?" (a reference to pub regular, the journalist Jeffrey Bernard).

At various times, Private Eye has also used the work of Ralph Steadman, Wally Fawkes, Timothy Birdsall, Martin Honeysett, Willie Rushton, Gerald Scarfe, Robert Thompson, Ken Pyne, Geoff Thompson, "Jerodo", Ed McLauchlan, "Pearsall", Kevin Woodcock, Brian Bagnall, Kathryn Lamb and George Adamson.

Other media and merchandise

Private Eye has from time to time produced various spin-offs from the magazine, including:

- Books, e.g. annuals, cartoon collections and investigative pamphlets;

- Audio recordings;

- Private Eye TV, a 1971 BBC TV version of the magazine; and

- Memorabilia and commemorative products, such as Christmas cards.

Criticism and controversy

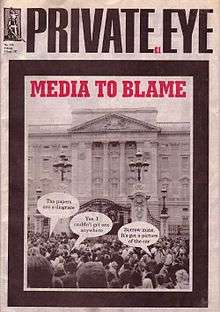

Princess Diana

Some have found the magazine's irreverence and sometimes controversial humour offensive. Following the death of Princess Diana in 1997, Private Eye printed a cover headed "Media to blame". Under this headline was a picture of many hundreds of people outside Buckingham Palace, with one person commenting that the papers were "a disgrace", another agreeing, saying that it was impossible to get one anywhere, and another saying, "Borrow mine. It's got a picture of the car."[13]

Following the abrupt change in reporting from newspapers immediately following her death, the issue also featured a mock retraction from "all newspapers" of everything negative that they had ever said about Diana. This was enough to cause a flood of complaints and the temporary removal of the magazine from the shelves of some newsagents. These included WHSmith, which had previously refused to stock Private Eye until well into the 1970s, and was characterised in the magazine as "WH Smugg" or "WH Smut" on account of its policy of stocking pornographic magazines. The "Diana issue" is now one of the most highly sought-after back-issues.

Similar complaints

The issues that followed the Ladbroke Grove rail crash in 1999 (number 987), the September 11 attacks of 2001 (number 1037; the magazine even including a special "subscription cancellation coupon" for disgruntled readers to send in) and the Soham murders of 2002 all attracted similar complaints. Following the 7/7 London bombings the magazine's cover (issue number 1137) featured Prime Minister Tony Blair saying to London mayor Ken Livingstone: "We must track down the evil mastermind behind the bombers...", to which Livingstone replies: "...and invite him around for tea", in reference to his controversial invitation of the Islamic theologian Yusuf al-Qaradawi to London.[14]

MMR vaccine

During the early 2000s Private Eye published many stories on the MMR vaccine controversy, substantially supporting the interpretation by Andrew Wakefield of published research in The Lancet by the Royal Free Hospital's Inflammatory Bowel Disease Study Group, which described an apparent link between the vaccine and autism and bowel problems. Many of these stories accused medical researchers who supported the vaccine's safety of having conflicts of interest because of funding from the pharmaceutical industry.

Initially dismissive of Wakefield, the magazine rapidly moved to support him, in 2002 publishing a 32-page MMR Special Report that supported Wakefield's assertion that MMR vaccines "should be given individually at not less than one year intervals." The British Medical Journal issued a contemporary press release[15] that concluded: "The Eye report is dangerous in that it is likely to be read by people who are concerned about the safety of the vaccine. A doubting parent who reads this might be convinced there is a genuine problem and the absence of any proper references will prevent them from checking the many misleading statements." Subsequently, editor Ian Hislop told the author and columnist Ben Goldacre that Private Eye is "not anti-MMR".[16]

In a review article published in 2010, after Wakefield was disciplined by the General Medical Council, regular columnist Phil Hammond, who contributes to the "Medicine Balls" column under the pseudonym "MD", stated that: "Private Eye got it wrong in its coverage of MMR", in maintaining its support for Wakefield's position long after shortcomings in his work had emerged.[17]

Bigotry

The cover of issue 256 in 1971 showed Emperor Hirohito visiting Britain with the caption "A nasty nip in the air", and the subheading "Piss off, Bandy Knees".[18][19] The New Statesman said in 1997 that this was viewed as "rather jolly" at the time,[20] and according to The New Yorker: "Hirohito could not have expected much better, and bore the abuse courteously."[19]

In the 1960s and 1970s the magazine mocked the gay rights movement and feminism. The magazine mocked the Gay Liberation Front[21] and gay rights activism as "Poove Power"[22] (effectively coining the term "poove" as a derogatory insult for gay men[23]), and published feminist material under the title "Loony Feminist Nonsense".[24]

Senior figures in the trade union Unite have accused the publication of having a classist anti-union bias, with former member of the Communist Party of Great Britain and Unite chief of staff Andrew Murray describing Private Eye as "a publication of assiduous public school boys" and adding that it has allegedly "never once written anything about trade unions that isn't informed by cynicism and hostility".[25] The far-left newspaper Socialist Worker also wrote that "For the past 50 years, the satirical magazine Private Eye has upset and enraged the powerful. Its mix of humour and investigation has tirelessly challenged the hypocrisy of the elite. ... But it also has serious weaknesses. Among the witty — if sometimes tired — spoof articles and cartoons, there is a nasty streak of snobbery and prejudice. Its jokes about the poor, women and young people rely on lazy stereotypes you might expect from the columns of the Daily Mail. It is the anti-establishment journal of the establishment."[26]

Blasphemy

The 2004 Christmas issue received a number of complaints after it featured Pieter Bruegel's painting of a nativity scene, in which one wise man said to another: "Apparently, it's David Blunkett's" (who at the time was involved in a scandal in which he was thought to have impregnated a married woman). Many readers sent letters accusing the magazine of blasphemy and anti-Christian attitudes. One stated that the "witless, gutless buggers wouldn't dare mock Islam". It has, however, regularly published Islam-related humour such as the cartoon which portrayed a "Taliban careers master asking a pupil: What would you like to be when you blow up?".[27] Many letters in the first issue of 2005 disagreed with the former readers' complaints, and some were parodies of those letters, "complaining" about the following issue's cover[28] – a cartoon depicting Santa's sleigh shredded by a wind farm: one said: "To use a picture of Our Lord Father Christmas and his Holy Reindeer being torn limb from limb while flying over a windfarm is inappropriate and blasphemous."

Litigation

Private Eye has long been known for attracting libel lawsuits, which in English law can lead to the award of damages relatively easily. The publication maintains a large quantity of money as a "fighting fund" (although the magazine frequently finds other ways to defuse legal tensions, for example by printing letters from aggrieved parties). As editor since 1986, Ian Hislop is reportedly one of the most sued people in Britain.[29] From 1969 to the mid-1980s, the magazine was represented by human rights lawyer Geoffrey Bindman.[30]

The first person to successfully sue Private Eye was the writer Colin Watson, who objected to the magazine's description of him as "the little-known author who ... was writing a novel, very Wodehouse but without the jokes". He was awarded £750.[31]

For the tenth anniversary issue in 1971 (number 257), the cover showed a cartoon headstone inscribed with a long list of well-known names, and the epitaph: "They did not sue in vain".[32]

In the case of Arkell v. Pressdram (1971), the plaintiff was the subject of an article.[33] Arkell's lawyers wrote a letter which concluded: "His attitude to damages will be governed by the nature of your reply." Private Eye responded: "We acknowledge your letter of 29th April referring to Mr J. Arkell. We note that Mr Arkell's attitude to damages will be governed by the nature of our reply and would therefore be grateful if you would inform us what his attitude to damages would be, were he to learn that the nature of our reply is as follows: fuck off."[34] In the years following, the magazine would refer to this exchange as a euphemism for a blunt and coarse dismissal, for example: "We refer you to the reply given in the case of Arkell v. Pressdram".[35][36] As with "tired and emotional" this usage has spread beyond the magazine.

Another litigation case against the magazine was initiated by James Goldsmith, who managed to arrange for criminal libel charges to be brought, meaning that, if found guilty, those behind the Eye could be imprisoned. He sued over allegations that members of the Clermont Set, including Goldsmith, had conspired to shelter Lord Lucan after Lucan had murdered his family nanny, Sandra Rivett. Goldsmith won a partial victory and eventually reached a settlement with the magazine. The case threatened to bankrupt Private Eye, which turned to its readers for financial support in the form of a "Goldenballs Fund". Goldsmith himself was referred to as "Jaws". The solicitor involved in many litigation cases against Private Eye, including the Goldsmith case, was Peter Carter-Ruck,[37] whose firm the magazine refers to this day as "Carter-Fuck".[38]

Robert Maxwell sued the magazine for the suggestion he looked like a criminal, and won a significant sum. Editor Hislop summarised the case: "I've just given a fat cheque to a fat Czech", and later claimed this was the only known example of a joke being told on News at Ten.

Sonia Sutcliffe sued after allegations made in January 1981 that she used her connection to her husband, the "Yorkshire Ripper" Peter Sutcliffe, to make money.[39] She won £600,000 in damages in May 1989, a record at the time, which was reduced to £60,000 on appeal by Private Eye.[40] However, the initial award caused Hislop to quip outside the court: "If that's justice, then I'm a banana."[41] Readers raised a considerable sum in the "Bananaballs Fund", and Private Eye scored a public relations coup by donating the surplus to the families of Peter Sutcliffe's victims. Later, in Sonia Sutcliffe's libel case against the News of the World in 1990, details emerged which demonstrated that she had benefited financially from her husband's crimes, even though Private Eye's facts had been inaccurate.[39]

In 1994, Gordon Anglesea successfully sued the Eye for publishing allegations that he had indecently assaulted under-aged boys. In 2016 he was convicted for historic sex offences.[42] Hislop stated that the magazine would not attempt to recover the £80,000 in damages Anglesea received, stating: "I can’t help thinking of the witnesses who came forward to assist our case at the time, one of whom later committed suicide telling his wife that he never got over not being believed. Private Eye will not be looking to get our money back from the libel damages. Others have paid a far higher price."[43]

A rare victory for the magazine came in late 2001, when a libel case brought against it by a Cornish chartered accountant, Stuart Condliffe, finally came to trial after ten years. The case was thrown out after only a few weeks as Condliffe had effectively accused his own legal team (Carter-Ruck) of lying.

In 2009 Private Eye successfully challenged an injunction brought against it by Michael Napier, the former head of the Law Society, who had sought to claim "confidentiality" for a report that he had been disciplined by the Law Society in relation to a conflict of interest.[44] The ruling had wider significance in that it allowed other rulings by the Law Society to be publicised.[45][46]

Ownership

The magazine is owned by an eclectic group of people, officially published through the mechanism of a limited company called Pressdram Ltd,[47] which was bought as an "off the shelf" company by Peter Cook in November 1961.

Private Eye does not publish explicit details of individuals concerned with its upkeep (and does not contain a list of its editors, writers and designers). In 1981 the book The Private Eye Story stated that the owners were Peter Cook (who owned most of the shareholding) with smaller shareholders including Dirk Bogarde, Jane Asher, and several of those involved with the founding of the magazine. Most of those on the list have since died, however, and it is unclear what happened to their shareholdings. Those concerned are reputedly contractually only able to sell their shareholdings at the price they originally paid for them.

Shareholders as of the annual company return dated 31 March 2016, including shareholders who have inherited shares, are:

- Jane Asher

- David Cash (also a director)

- Elizabeth Cook

- Lin Cook

- Ian Hislop (also a director)

- executors of the estate of Lord Faringdon

- Peter Cook (Productions) Ltd

- Private Eye (Productions) Ltd

- Anthony Rushton (also a director)

- Sarah Seymour

- Thomas Usborne

- Brock van der Bogaerde

The other directors are Sheila Molnar and Geoff Elwell, who is also the company secretary.

Within its pages the magazine always refers to its owner as "Lord Gnome", a satirical dig at autocratic press barons.

Logo

The magazine's masthead features a cartoon logo of an armoured knight, Gnitty, with a bent sword, parodying the "Crusader" logo of the Daily Express.

The logo for the magazine's news page is a donkey-riding naked Mr Punch caressing his erect and oversized penis, while hugging a female admirer. It is a detail from a frieze by "Dickie" Doyle that once formed the masthead of Punch magazine, which the editors of Private Eye had come to loathe for its perceived descent into complacency. The image, hidden away in the detail of the frieze, had appeared on the cover of Punch for nearly a century and was noticed by Malcolm Muggeridge during a guest-editing spot on Private Eye. The "Rabelaisian gnome", as the character was called, was enlarged by Gerald Scarfe, and put on the front cover of issue 69 in 1964 at full size. He was then formally adopted as a mascot on the inside pages, as a symbol of the old, radical incarnation of Punch magazine that the Eye admired.

The masthead text was designed by Matthew Carter, who would later design the popular webfonts Verdana and Georgia, and the Windows 95 interface font Tahoma.[48] He wrote that, "Nick Luard [then co-owner] wanted to change Private Eye into a glossy magazine and asked me to design it. I realised that this was a hopeless idea once I had met Christopher Booker, Richard Ingrams and Willie Rushton."[49]

See also

References

- ↑ "Private Eye – circulation". ABC. 13 August 2015. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- ↑ Dowell, Ben (16 February 2012). "Private Eye hits highest circulation for more than 25 years". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 28 March 2013.

- ↑ "Andrew Osmond – Obituary". The Guardian. 19 April 1999.

- ↑ "Richard Ingrams interview" (PDF). Press Gazette. 15 December 2005. Retrieved 16 September 2013.

- ↑ "Not Private Eye, Tony Quinn". Magforum.com. 21 November 2012. Retrieved 16 September 2013.

- ↑ James, Brian (28 February 1987). "The orchestra that opened up". The Times.

- 1 2 John Crace (4 February 2010). "Private Eye proves the old jokes are the best". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

The success of the satirical magazine is largely down to its familiar humour ... Private Eye has just recorded its best sales figures since 1992. But forget the investigations and the weekly regulars, it's those little, recurring, long-standing jokes that make the difference. ... Ron Knee, aged 59: The quintessential British football manager began life in the 1960s and has remained the inspirational driving force of Neasden FC and all subsequent football journalism. Knee's two greatest signings have been the ever-present one-legged goal keeper Wally Foot, and own-goal specialist Baldy Pevsner. Knee's appearances have been increasingly rare since Ian Hislop took over as Private Eye editor, but he does still occasionally get a run in the first team. Keen observers of Hislop's diary may notice Knee's outings invariably coincide with the editor's holidays.

- ↑ John Sutherland (1 March 2004). "The fictional Sally Jockstrap". London: Guardian. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ↑ Richard Ingrams's week (12 June 2005). "Diary: Dishonourable, dishonest". The Observer. Retrieved 15 August 2013.

- ↑ Robertson, Wilmot (1993). Instauration, Volumes 19–20. Howard Allen Enterprises, Inc. p. 30.

- ↑ The Paul Foot Award for campaigning journalism

- ↑ "Celeb rocks on and on". BBC News. 6 September 2002. Retrieved 15 August 2013.

- ↑ "Private Eye Issue 932". Retrieved 15 June 2007.

- ↑ "Private Eye Issue 1137". Retrieved 15 June 2007.

- ↑ Home. "Press: Private Eye Special Report on MMR – Elliman and Bedford 324 (7347): 1224 Data Supplement – Longer version". BMJ. doi:10.1136/bmj.324.7347.1224. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ↑ "The media's MMR hoax – Bad Science". Badscience.net. 30 August 2008. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2010.01.014. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ↑ "Second Opinion: the Editor asks M.D. to peer review Private Eye's MMR coverage". Private Eye. Pressdram (1256): 17. February 2010.

- ↑ "Private Eye Issue 256". Retrieved 15 June 2007.

- 1 2 The New Yorker. 69. New Yorker Magazine, Incorporated. May 1993. p. 52.

- ↑ New Statesman, New Society. Statesman & Nation Publishing Company Limited. 1997. p. 47.

- ↑ Dominic Sandbrook (12 October 2010). State of emergency: the way we were : Britain, 1970-1974. Allen Lane. p. 403.

- ↑ "pelib | Flickr – Condivisione di foto!". Flickr.com. 19 December 2007. Retrieved 15 August 2013.

- ↑ Dominic Strinati; Stephen Wagg (24 February 2004). Come on Down?: Popular Media Culture in Post-War Britain. Routledge. pp. 264–. ISBN 978-1-134-92368-7.

- ↑ Geoffrey Hughes (13 September 2011). Political Correctness: A History of Semantics and Culture. John Wiley & Sons. p. 219. ISBN 978-1-4443-6029-5.

- ↑ 'Blackleg' (15 April 2016). "TUC News". Private Eye (1416). p. 20.

...Unite chief of staff Andrew Murray made much of the Eye's coverage of [the expulsion of David Beaumont from Unite], telling the panel: "Private Eye is... a publication of assiduous [sic] public school boys which has never, never once written anything about trade unions that isn't informed by cynicism and hostility."

- ↑ Ward, Patrick (1 November 2011). "Private Eye: The First 50 Years". Socialist Worker (2276). Socialist Workers Party. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- ↑ ""Andy McSmith's Diary" - The Independent". Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- ↑ "Private Eye Issue 1122". Retrieved 15 June 2007.

- ↑ Byrne, Ciar (23 October 2006). "Ian Hislop: My 20 years at the "Eye"". London: The Independent. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- ↑ Robins, Jon (13 November 2001). "Forty years old and fighting fit". The Independent. UK. Retrieved 22 July 2011.

- ↑ Kim Bunce. "The needle of the Eye | Media". The Observer. Retrieved 2014-01-05.

- ↑ "pictures/covers/full/257_big". private-eye.co.uk. Retrieved 7 May 2014.

- ↑ "Correspondence in full". nasw.org. Retrieved 7 May 2014.

- ↑ Private Eye, Issues 263-264; Issues 266-283; Issues 286-288, page ccxxvii

- ↑ Macqueen 2011, pp. 27,28

- ↑ "Letters". Private Eye. London: Pressdram Ltd (1221): 13. October 2008.

Mr Callaghan is referred to the Eye's reply in the famous case of Arkell v. Pressdram (1971).

- ↑ "A-list libel lawyer dies". BBC News. 21 December 2003.

- ↑ "Obituary: Peter Carter-Ruck". The Independent. 22 December 2003. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- 1 2 Greenslade, Roy (2004). Press Gang: How Newspapers Make Profits From Propaganda. London: Pan Macmillan. pp. 440–41.

- ↑ "On This Day, 1989". BBC. 2008. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- ↑ "Private Eye – 40 not out ... yet". BBC News. 25 October 2001.

- ↑ Gordon Anglesea: Former policeman sentenced to 12 years, 2016-11-04, retrieved 2016-11-05

- ↑ "Private Eye won't seek repayment of damages after Gordon Anglesea conviction as 'others have paid a far higher price' – Press Gazette". www.pressgazette.co.uk. Retrieved 2016-11-05.

- ↑ Archived 30 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Gibb, Frances (21 May 2009). "Failure to gag Private Eye clears the way to publication of rulings against lawyers". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 11 June 2011.

- ↑ "Private Eye Wins Case!". Private Eye. London: Pressdram Ltd (1237): 6–7. 29 May 2009.

- ↑ "Pressdram". WebCHeck – Company Details. Companies House. Retrieved 6 December 2007.

PRESSDRAM LIMITED

C/O MORLEY AND SCOTT

LYNTON HOUSE

7–12 TAVISTOCK SQUARE

LONDON WC1H 9LT

Company No. 00708923

Date of Incorporation: 24 November 1961 - ↑ Walters, John. "Matthew Carter's timeless typographic masthead for Private Eye magazine". Eye. Retrieved 24 August 2015.

- ↑ Carter, Matthew. "Carter's Battered Stat". Eye. Retrieved 5 February 2016.

Further reading

- Carpenter, Humphrey (2002). That Was Satire That Was. Phoenix. ISBN 0-7538-1393-9.

- Hislop, Ian (1990). The Complete Gnome Mart Catalogue. Corgi. ISBN 0552137529.

- Ingrams, Richard (1993). Goldenballs!. Harriman House. ISBN 1897597037.

- Ingrams, Richard (1971). The Life and Times of Private Eye. Penguin. ISBN 0-14-003357-2.

- Macqueen, Adam (2011). Private Eye: The First 50 Years – An A–Z. London: Private Eye Productions. ISBN 978-1-901784-56-5.

- Marnham, Patrick (1982). The Private Eye Story. Andre Deutsch/Private Eye. ISBN 0-233-97509-8.

External links

- Official website

- Media top 100: 40. Ian Hislop at the Wayback Machine (archived 7 March 2004)

Coordinates: 51°30′53″N 0°08′01″W / 51.514657°N 0.133652°W