Principality of Hungary

| Principality of Hungary | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magyar Nagyfejedelemség | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Esztergom and Székesfehérvár (from the reigns of Taksony and Géza) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Gyula-Kende sacred diarchy (early) Tribal confederation | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Kende | Kurszán (?–c. 904) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Grand Prince (gyula) |

Árpád (c. 895–c. 907) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Zoltán (c. 907–c. 947) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Fajsz (c. 947–c. 955) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Taksony (c. 955–c. 972) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Géza (c. 972–997) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stephen (997–1000) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Middle ages | |||||||||||||||||||||

| • | Established | c. 895 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| • | ended at the coronation of Stephen I |

25 December 1000 or 1 January 1001 1000 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | | |||||||||||||||||||||

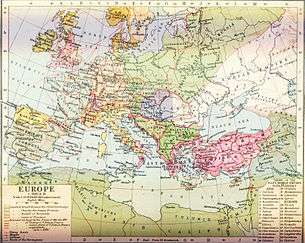

The Principality of Hungary[1][2][3][4][5][6][7] or Duchy of Hungary[8][9] (Hungarian: Magyar Nagyfejedelemség: "Hungarian Grand Principality")[10] was the earliest documented Hungarian state in the Carpathian Basin, established 895 or 896,[11][12][13][14][15] following the 9th century Hungarian conquest of the Carpathian Basin.

The Hungarians, a semi-nomadic people forming a tribal alliance[13][16][17][18] led by Árpád, arrived from Etelköz which was their earlier principality east of the Carpathians.[19]

During the period, the power of the Hungarian Grand Prince seemed to be decreasing irrespective of the success of the Hungarian military raids across Europe. The tribal territories, ruled by Hungarian warlords (chieftains), became semi-independent polities (e.g. domains of Gyula the Younger in Transylvania). These territories got united again only under the rule of St Stephen. The semi-nomadic Hungarian population adopted settled life. The chiefdom society changed to a state society. From the second half of the 10th century, Christianity started to spread. The principality was succeeded by the Christian Kingdom of Hungary with the coronation of St Stephen I at Esztergom on Christmas Day 1000 (its alternative date is 1 January 1001).[20][21][22]

The Hungarian historiography calls the entire period from 896 to 1000 "the age of principality".[14]

Name

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Hungary | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||

|

Medieval

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Early modern

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Late modern

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Contemporary

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

By topic |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

The ethnonym of the Hungarian tribal alliance is uncertain. According to one view, following Anonymus's description, the federation was called "Hetumoger / Seven Magyars" ("VII principales persone qui Hetumoger dicuntur", "seven princely persons who are called Seven Magyars"[23]), though the word "Magyar" possibly comes from the name of the most prominent Hungarian tribe, called Megyer. The tribal name "Megyer" became "Magyar" referring to the Hungarian people as a whole.[24][25] Written sources called Magyars "Hungarians" prior to the conquest of the Carpathian Basin when they still lived on the steppes of Eastern Europe (in 837 "Ungri" mentioned by Georgius Monachus, in 862 "Ungri" by Annales Bertiniani, in 881 "Ungari" by the Annales ex Annalibus Iuvavensibus).

In contemporary Byzantine sources, written in Greek, the country was known as "Western Tourkia"[26][27] in contrast to eastern or Khazar Tourkia. The Jewish Hasdai ibn Shaprut around 960 called the polity "the land of the Hungrin" (the land of the Hungarians) in a letter to Joseph of the Khazars.[28]

History

Background

On the eve of the arrival of the Hungarians (Magyars), around 895, East Francia, the First Bulgarian Empire and Great Moravia (a vassal state of East Francia)[29] ruled the territory of the Carpathian Basin. The Hungarians had much knowledge about this region because they were frequently hired as mercenaries by the surrounding polities and had led their own campaigns in this area for decades.[30] This area had been sparsely populated,[3][31] since Charlemagne’s destruction of the Avar state in 803 and the Magyars (Hungarians) were able to move in virtually unopposed, peacefully.[32] The newly unified Hungarians led by Árpád settled in the Carpathian Basin starting in 895. The East Frankish vassal Balaton Principality in Transdanubia was subjugated during a Hungarian campaign in the direction of Italy around 899-900. Great Moravia was annihilated between 902 and 907 and part of it, the former Principality of Nitra, became part of the Hungarian state. The south-eastern parts of the Carpathian Basin were under the rule of the First Bulgarian Empire, however the Bulgarians lost their dominance due to the Hungarian conquest. The control prior to the Hungarian settlement of territory of Solitudo Avarorum (mostly the northern part of Great Hungarian Plain), where remnants of the Avars lived, has not yet been entirely clarified.

Military achievements

The principality as a warrior state,[1] with a new-found military might, conducted vigorous raids ranging widely from Constantinople to central Spain, and defeated no fewer than three major east Frankish armies between 907 and 910.[33] The Hungarians succeeded in extending the de iure Bavarian-Hungarian border to the River Enns (until 955),[34] and the principality was not attacked from this direction for 100 years after the Battle of Pressburg.[21] The intermittent Hungarian campaigns lasted until 970, however two military defeats in 955 (Lechfeld) and 970 (Arcadiopolis) marked a shift in the evolution of the Hungarian principality.[35]

Transition

The change from a ranked chiefdom society to a state society was one of the most important developments during this time.[36] Initially, the Magyars retained a semi-nomadic lifestyle, practising transhumance: they would migrate along a river between winter and summer pastures, finding water for their livestock.[37] According to Györffy's theory[38] derived from placenames, Árpád's winter quarters -clearly after his occupation of Pannonia in 900- were possibly in 'Árpádváros' (Árpád's town), now a district of Pécs, and his summer quarters -as confirmed by Anonymus- were on Csepel Island.[37] Later, his new summer quarters were in Csallóköz[37] according to this theory, however the exact location of the early center of the state is disputed. According to Gyula Kristó the center was located between the Danube and Tisza rivers,[38] however the archaeological findings imply the location in the region of the Upper Tisza.[38]

Constantine VII's De Administrando Imperio, written around 950 AD, tries to define precisely the whole land of the Hungarians Tourkia.[39] Constantine described the previous inhabitants of Hungary (e.g. Moravians), determined early Hungarian settlements, located Hungarian rivers (Temes, Maros, Körös, Tisza, Tutisz), gave the neighbors of the Hungarians.[39] Constantine had much more knowledge about the eastern parts of Hungary, therefore, according to one theory, Tourkia did not mean the land of the whole federation but a tribal settlement and the source of the description of Hungary could have been Gyula whose tribe populated the five rivers around 950.[39] According to another hypothesis, mainly based on Constantine's description, the Hungarians started to really settle western Hungary (Transdanubia) only after 950, because the eastern parts of the country was more suitable for a nomadic lifestyle.[39]

Due to changed economic circumstances, insufficient pasturage to support a nomad society and the impossibility of moving on,[40] the semi-nomadic Hungarian lifestyle began to change and the Magyars adopted a settled life and turned to agriculture,[29] though the start of this change can be dated to the 8th century.[6] The society became more homogeneous: the local Slavic and other populations merged with the Hungarians.[40] The Hungarian tribal leaders and their clans established fortified centers in the country and later their castles became centers of the counties.[32] The whole system of Hungarian villages developed in the 10th century.[37]

Fajsz and Taksony, the Grand Princes of the Hungarians, began to reform the power structure.[41][42] They invited Christian missionaries for the first time and built forts.[41] Taksony abolished the old center of the Hungarian principality (possibly at Upper Tisza) and sought a new one at Székesfehérvár[42] and Esztergom.[43] Taksony also reintroduced the old style military service, changed the weaponry of the army, and implemented large-scale organized resettlements of the Hungarian population.[42]

The consolidation of the Hungarian state began during the reign of Géza.[44] After the battle of Arcadiopolis, the Byzantine Empire was the main enemy of the Hungarians.[45] The Byzantine expansion threatened the Hungarians, since the subjugated First Bulgarian Empire was in alliance with the Magyars at that time.[45] The situation became more difficult for the principality when the Byzantine Empire and the Holy Roman Empire made an alliance in 972.[45] In 973, twelve illustrious Magyar envoys, whom Géza had probably appointed, participated in the Diet held by Otto I, Holy Roman Emperor. Géza established close ties with the Bavarian court, inviting missionaries and marrying his son to Gisela, daughter of Duke Henry II.[40] Géza of the Árpád dynasty, Grand Prince of the Hungarians, who ruled only part of the united territory, the nominal overlord of all seven Magyar tribes, intended to integrate Hungary into Christian Western Europe, rebuilding the state according to the Western political and social model. Géza's eldest son St Stephen (István, Stephen I of Hungary) became the first King of Hungary after defeating his uncle Koppány, who also claimed the throne. The unification of Hungary, the foundation of the Christian state[46] and its transformation into a European feudal monarchy was accomplished by Stephen.

Christianization

The new Hungarian state was on the frontier of Christendom.[40] From the second half of the 10th century, Christianity flourished as Catholic missionaries arrived from Germany. Between 945 and 963, the main office-holders of the Principality (the Gyula, and the Horka) agreed to convert to Christianity.[47][48] In 973 Géza I and all his household were baptised, and a formal peace concluded with Emperor Otto I; however he remained essentially pagan even after his baptism:[19] Géza had been educated by his father Taksony as a pagan prince.[49] The first Hungarian Benedictine monastery was founded in 996 by Prince Géza. During Géza's reign, the nation conclusively renounced its nomadic way of life and within a few decades of the battle of Lechfeld became a Christian kingdom.[19]

Organization of the state

Until 907 (or 904), the Hungarian state was under joint rule (adopted from the Khazars). The kingship had been divided between the sacral king (some sources report the title prince[50] or khan[51]) Kende and the military leader gyula. It is not known which of the two roles were assigned to Árpád and which to Kurszán. Possibly, after the Kende Kurszán's death, this division ceased and Árpád became the sole ruler of the principality. The Byzantine Constantine Porphyrogennetos called Árpád "ho megas Tourkias archon" (the great prince of Tourkia),[52] and all of the 10th-century princes who ruled the country held this title.[5] According to the Agnatic seniority the oldest members of the ruling clan inherited the principality. The Grand Princes of Hungary probably did not hold superior power, because during the military campaigns to the west and to the south the initially strong[53] princely power had decreased.[52] Moreover, the records do not refer to Grand Princes in the first half of the 10th century, except in one case, where they mention Taksony as 'duke of Hungary' (Taxis-dux, dux Tocsun) in 947.[52] The role of military leaders (Bulcsú, Lél) grew more significant.[52] The princes of the Árpád dynasty bore Turkic names as did the majority of the Hungarian tribes.[14]

Titles

- Kende (in Arabic sources) or megas archon (in Byzantine sources), rex (in Latin sources), the Grand Prince of Hungarians (after 907 CE)

- Gyla or djila (gyula) or magnus princeps (in western sources), the military leader[52] (second rank),[52] the Grand Prince of Hungarians[52]

- Horca, Kharkhas, the judge[54] (third rank)[52]

Population

There are various estimates of the size of the country's population in the 10th century. Estimates are ranging from 250,000 to 1,500,000 in 900 AD. There is no archaeological evidence that the Hungarian nobles lived in castles in the 10th century.[55] Archaeology revealed only one fortified building dated to the late 9th century (the castle of Mosapurc).[56] Only excavations of 11th century buildings give certain evidence of castle building processes.[56] However, the result of the excavations in Borsod may imply that the prelates and the nobles had already lived in stone houses in the 10th century.[57] Muslim geographers mentioned that Hungarians were tent inhabitants.[58] Beside tents, the common people lived in pit-dwellings, though there is archaeological proof of the appearance of more-roomed[59] and wood-and-stone house types.[60]

Further theories

There are professional historians telling that Prince Árpád's people spoke Turkic and the Magyars had already been in the Basin (from 680). Their main argument is that the newcomers' cemeteries are too small, they were not enough to fill up the Basin with the Magyar language. But it seems that Árpád led the Megyer tribe, and it would be tricky if the Megyer tribe would have spoken Bulgar Turkic. Of course, in principle anything may happen in a symbiosis.[61]

See also

References

- 1 2 S. Wise Bauer, The history of the medieval world: from the conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade, W. W. Norton & Company, 2010, p. 586

- ↑ George H. Hodos, The East-Central European region: an historical outline, Greenwood Publishing Group, 1999, p. 19

- 1 2 Alfried Wieczorek, Hans-Martin Hinz, Council of Europe. Art Exhibition, Europe's centre around AD 1000, Volume 1, Volume 1, Theiss, 2000, pp. 363-372

- ↑ Ferenc Glatz, Magyar Történelmi Társulat, Etudes historiques hongroises 1990: Environment and society in Hungary, Institute of History of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, 1990, p. 10

- 1 2 Acta historica, Volumes 105-110, József Attila Tudom. Bölcs. Kar, 1998, p. 28

- 1 2 Antal Bartha, Hungarian society in the 9th and 10th centuries, Akadémiai Kiadó, 1975, pp- 53-84, ISBN 978-963-05-0308-2

- ↑ Oksana Buranbaeva, Vanja Mladineo, Culture and Customs of Hungary, ABC-CLIO, 2011, p. 19

- ↑ Colin Davies, The emergence of Western society: European history A.D. 300-1200, Macmillan, 1969, p. 181

- ↑ Jennifer Lawler, Encyclopedia of the Byzantine Empire, McFarland & Co., 2004, p.13

- ↑ Hadtörténelmi közlemények, Volume 114 , Hadtörténeti Intézet és Múzeum, 2001, p. 131

- ↑ The encyclopedia Americana, Volume 14, Grolier Incorporated, 2002, p. 581

- ↑ Encyclopedia Americana, Volume 1, Scholastic Library Pub., 2006, p. 581

- 1 2 Louis Komzsik, Cycles of Time: From Infinity to Eternity, Trafford Publishing, 2011 p. 54

- 1 2 3 Acta orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae, Volume 36 Magyar Tudományos Akadémia (Hungarian Academy of Sciences), 1982, p. 419

- ↑ Zahava Szász Stessel, Wine and thorns in Tokay Valley: Jewish life in Hungary : the history of Abaújszántó, Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press, 1995, p. 47

- ↑ Peter Linehan, Janet Laughland Nelson. 2001. p. 79

- ↑ Anatoly Michailovich Khazanov,André Wink. 2001. p. 103

- ↑ Lendvai. 2003. p. 15

- 1 2 3 Paul Lendvai, The Hungarians: a thousand years of victory in defeat, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, 2003, p. 15-29, p. 533

- ↑ University of British Columbia. Committee for Medieval Studies, Studies in medieval and renaissance history, Committee for Medieval Studies, University of British Columbia, 1980, p. 159

- 1 2 Peter F. Sugar,Péter Hanák A History of Hungary, Indiana University Press, 1994, pp 12-17

- ↑ Pál Engel, Tamás Pálosfalvi, Andrew Ayton, The Realm of St. Stephen: A History of Medieval Hungary, 895-1526, .B.Tauris, 2005, p. 27

- ↑ Gyula Decsy, A. J. Bodrogligeti, Ural-Altaische Jahrbücher, Volume 63, Otto Harrassowitz, 1991, p. 99

- ↑ György Balázs, Károly Szelényi, The Magyars: the birth of a European nation, Corvina, 1989, p. 8

- ↑ Alan W. Ertl, Toward an Understanding of Europe: A Political Economic Précis of Continental Integration, Universal-Publishers, 2008, p. 358

- ↑ Peter B. Golden, Nomads and their neighbours in the Russian steppe: Turks, Khazars and Qipchaqs, Ashgate/Variorum, 2003. "Tenth-century Byzantine sources, speaking in cultural more than ethnic terms, acknowledged a wide zone of diffusion by referring to the Khazar lands as 'Eastern Tourkia' and Hungary as 'Western Tourkia.'" Carter Vaughn Findley, The Turks in the World History, Oxford University Press, 2005, p. 51, citing Peter B. Golden, 'Imperial Ideology and the Sources of Political Unity Amongst the Pre-Činggisid Nomads of Western Eurasia,' Archivum Eurasiae Medii Aevi 2 (1982), 37–76.

- ↑ Carter V. Findley, The Turks in world history, Oxford University Press, 2005, p. 51

- ↑ Raphael Patai, The Jews of Hungary: History, Culture, Psychology, Wayne State University Press, 1996, p. 29, ISBN 978-0814325612

- 1 2 Kirschbaum, Stanislav J. (1995). A History of Slovakia: The Struggle for Survival. New York: Palgrave Macmillan; St. Martin's Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-312-10403-0. Retrieved 2009-10-09. Cited: "Great Moravia was a vassal state of the Germanic Frankish Kingdom and paid an annual tribute to it."

- ↑ István Süli-Zakar, THE MOST IMPORTANT GEOPOLITICAL AND HISTOGEOGRAPHICAL QUESTIONS OF THE AGE OF THE CONQUEST AND THE FOUNDATION OF THE HUNGARIAN STATE, In: NEW RESULTS OF CROSS-BORDER CO-OPERATION, The Department of Social Geography and Regional Development Planning of the University of Debrecen & Institute for Euroregional Studies „Jean Monnet” European Centre of Excellence, 2011, p. 12, ISBN 978-963-89167-3-0

- ↑ Bryan Cartledge, Bryan Cartledge (Sir.), The will to survive: a history of Hungary, Timewell Press, 2006, p.6

- 1 2 Dora Wiebenson, József Sisa, Pál Lövei, The architecture of historic Hungary, MIT Press, 1998, p. 11, ISBN 978-0-262-23192-3

- ↑ Peter Heather, Empires and Barbarians, Pan Macmillan, 2011

- ↑ Clifford Rogers, The Oxford Encyclopedia of Medieval Warfare and Military Technology, Volume 1, Oxford University Press, 2010, p. 292

- ↑ Oksana Buranbaeva Culture and Customs of Hungary

- ↑ The New Hungarian quarterly, Volumes 31-32, Corvina Press, 1990, p. 140

- 1 2 3 4 Lajos Gubcsi, Hungary in the Carpathian Basin, MoD Zrínyi Media Ltd, 2011

- 1 2 3 Révész, László (03.1996). A honfoglaló magyarok Északkelet- Magyarországon. Új Holnap 41. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - 1 2 3 4 Günter Prinzing, Maciej Salamon, Byzanz und Ostmitteleuropa 950 - 1453: Beiträge einer table-ronde während des XIX. International Congress of Byzantine Studies, Copenhagen 1996, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, 1999, pp. 27-33

- 1 2 3 4 Nóra Berend, At the gate of Christendom: Jews, Muslims, and "pagans" in medieval Hungary, c. 1000-c. 1300, Cambridge University Press, 2001, p. 19

- 1 2 László Kósa, István Soós, A companion to Hungarian studies, Akadémiai Kiadó, 1999, p. 113

- 1 2 3 Révész, László (2010-12-20). Hunok, Avarok, Magyarok (Huns, Avars, Magyars) (PDF). Hitel folyóirat (Magazine of Hitel).

- ↑ Révész, László (02.2008). A Felső-Tisza-vidék honfoglalás kori temetői. História (Magazine of História). Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Stanislav J. Kirschbaum A History of Slovakia: The Struggle for Survival

- 1 2 3 József Attila Tudományegyetem., Bölcsészettudományi Kar (University of József Attila), Acta historica, Volumes 92-98, 1991, p. 3

- ↑ Miklós Molnár A Concise History of Hungary

- ↑ András Gerő, A magyar történelem vitatott személyiségei, Volume 3, Kossuth, 2004, p. 13, ISBN 978-963-09-4597-4

- ↑ Mark Whittow, The making of Byzantium, 600-1025, University of California Press, 1996, p. 294

- ↑ Ferenc Glatz, Magyarok a Kárpát-medencében, Pallas Lap- és Könyvkiadó Vállalat, 1988, p. 21

- ↑ Kevin Alan Brook, The Jews of Khazaria, Rowman & Littlefield, 2009, p. 253

- ↑ Victor Spinei, The Great Migrations in the East and South East of Europe from the Ninth to the Thirteenth Century: Hungarians, Pechenegs and Uzes, Hakkert, 2006, p. 42

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Timothy Reuter, The New Cambridge Medieval History: c. 900-c. 1024, Cambridge University Press, 1995, p. 543-545, ISBN 978-0-521-36447-8

- ↑ Michael David Harkavy, The new Webster's international encyclopedia: the new illustrated reference guide, Trident Press International, 1998, p. 70

- ↑ András Róna-Tas, A honfoglaló magyar nép, Balassi Kiadó Budapest, 1997, ISBN 963-506-140-4

- ↑ Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, p. 72.

- 1 2 Wolf & Takács 2011, p. 238.

- ↑ Wolf 2008, p. 14.

- ↑ Balassa 1997, p. 291.

- ↑ Wolf & Takács 2011, p. 209.

- ↑ Wolf 2008, pp. 13-14.

- ↑ Proto-Magyar Texts from the middle of 1st Middle of 1st Millenium? or Are they published or not? B. Lukács, President of Matter Evolution Subcommittee of the HAS. H-1525 Bp. 114. Pf. 49., Budapest, Hungary.

Secondary sources

- Balassa, Iván, ed. (1997). Magyar Néprajz IV. [Hungarian ethnography IV.]. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó. ISBN 963-05-7325-3.

- Berend, Nora; Urbańczyk, Przemysław; Wiszewski, Przemysław (2013). Central Europe in the High Middle Ages: Bohemia, Hungary and Poland, c. 900-c. 1300. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-78156-5.

- Wolf, Mária; Takács, Miklós (2011). "Sáncok, földvárak" ("Ramparts, earthworks") by Wolf; "A középkori falusias települések feltárása" ("Excavation of the medieval rural settlements") by Takács". In Müller, Róbert. Régészeti Kézikönyv [Handbook of archaeology]. Magyar Régész Szövetség. pp. 209–248. ISBN 978-963-08-0860-6.

- Wolf, Mária (2008). A borsodi földvár (PDF). Művelődési Központ, Könyvtár és Múzeum, Edelény. ISBN 978-963-87047-3-3.

Further reading

- Kozma, Gábor (Editor); et al. (December 2011). "New Results of Cross-Border Co-operation" (PDF). The Department of Social Geography and Regional Development Planning of the University of Debrecen; et al. Retrieved June 2, 2012. ISBN 9789638916730

.svg.png)