Presidency of Abraham Lincoln

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

President of the United States First term Second term Assassination and legacy

|

||

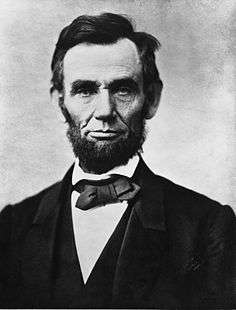

The presidency of Abraham Lincoln began on March 4, 1861, and ended with Lincoln's death by assassination on April 15, 1865, one month into his second term. This article details President Lincoln's actions during the American Civil War. Lincoln, despite being little prepared for it by prior military experience, was first and foremost a war president. The nation was at peace for less than six weeks of his presidency and it was the only presidency that was entirely "bounded by the parameters of war".[1] Lincoln was called on to handle both the political and military aspects of the war, and his leadership has to be evaluated based on his ability to balance these inseparable parts of the Union's efforts. He was a successful war president to the extent that he was able to control the revolutionary forces unleashed by his election and Southern secession, maintain the democratic principles that were the bedrock of the nation, and achieve a military victory.[2] His assassination five days after the end of the war left the final challenge of reconstructing the nation to others, but Lincoln as early as 1863 established principles that he felt should shape this process.[3] Lincoln, as commander-in-chief, suspended habeas corpus for prisoners suspected of supporting the Southern cause.

Lincoln, a former Whig politician, ran as a Republican on a political platform opposing the policies of the Pierce and Buchanan administrations that would have preserved slavery for the foreseeable future. While acknowledging that only a state could outlaw slavery within its own borders, the Republican insistence on keeping slavery out of all territories would ultimately lead to the end of slavery in the entire nation since, in the minds of both most Northerners and most Southerners, the survival of slavery depended on its ability to expand.[4] By his nature, Lincoln was open to political compromises, but, from his election to his assumption of office, he led his party in standing firm against any compromise on the territorial issues. After being sworn in as President he likewise refused to accept any resolution that would result in Southern secession from the Union.

Lincoln is ranked by historians as one of the greatest presidents in American history, usually as number one, for winning the Civil War, bringing the nation back together as one, and abolishing slavery.

Secession winter 1860–1861

President-elect in Springfield

As Lincoln's election became more probable, secessionists made it clear that their states would leave the Union. With his election on November 6, 1860, South Carolina declared its secession on December 20, followed by Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas. State militias in the seceding states occupied federal forts and confiscated the contents of federal arsenals. The upper South (Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, Kentucky, Missouri, and Arkansas) rejected immediate secession, but threatened to exit if the federal government attempted to coerce the seceded states. President Buchanan announced that secession was illegal while denying that the government had any power to resist it. Lincoln would have no official ability to act until his scheduled inauguration on March 4, 1861.[5]

Lincoln was in his hometown of Springfield on election day. He voted in mid-afternoon and spent the rest of the day discussing politics, primarily local, at the state capitol building. He took a few hours off at 5:00 to have dinner at home with his family. He returned to the capitol, but by 9:00 p.m. he had moved to the local telegraph office where he could observe first hand as the election returns were reported. It was after midnight before the final news reached Lincoln that he had carried New York and the election was his.[6]

As Lincoln received visitors and mail in Springfield, people repeatedly expressed their concern about events in the South. Many expected Lincoln to somehow provide reassurances to the South that their interests were not being threatened.[7] In a response to such an inquiry from the editor of the Democratic newspaper the Missouri Republican (its name went back to the Jackson era), Lincoln stated why he was reluctant to speak out:

The Republican newspapers now, and for some time past, are and have been republishing copious extracts from my many published speeches, which would at once reach the whole public if your class of papers would also publish them. I am not at liberty to shift my ground -- that is out of the question. If I thought a repetition would do any good I would make it. But my judgment is it would do positive harm. The secessionists, per se believing they had alarmed me, would clamor all the louder.[8]

Realizing that on one hand soothing words on the rights of slaveholders would alienate the Republican base, while taking a strong stand on the indestructibility of the Union could further inflame southerners, Lincoln chose a policy of silence. He believed that, given enough time without any overt acts or threats to the South, southern unionists would carry the day and bring their states back into the Union.[9]

At the suggestion of a southern merchant who contacted him, Lincoln did make an indirect appeal to the South by providing material for Lyman Trumball, a recognized Lincoln surrogate, to insert into his own public address. These words from Lincoln included, "I have labored in, and for, the Republican organization with entire confidence that whenever it shall be in power, each and all of the States will be left in as complete control of their own affairs respectively, and at as perfect liberty to choose, and employ, their own means of protecting property, and preserving peace and order within their respective limits, as they have ever been under any administration."[10] Lincoln was identified by the press as the author of these words. Republicans praised it, Democrats assailed it, and the South largely ignored it.[11]

Early military concerns

Shortly before the November election, the general-in-chief of the army, Winfield Scott, had prepared a memorandum for President Buchanan titled "Views suggested by imminent danger". Lincoln was provided a copy of the document. While believing that Lincoln's election would not lead to "any unconstitutional violence, or breach of law", Scott warned that there was a danger of "the seizure of a number of federal forts on the Mississippi River and on the Eastern coast -- including the vulnerable installations at Charleston harbor". Scott recommended that "all those works should be immediately so garrisoned as to make any attempt to take any one of them by surprise or coup de main ridiculous".[12] Buchanan dismissed Scott's suggestions as provocative to the South. Lincoln however responded by thanking Scott for the information and his patriotism.[13]

As the secession crisis deepened, Lincoln, along with much of the North, became concerned as southern states seized federal property. Reacting to a report that President Buchanan was about to surrender Fort Moultrie in Charleston, Lincoln said, "If that is true, they ought to hang him".[14] On December 21, through Congressman Elihu B. Washburne, he asked Scott "to be as well prepared as he can to either hold, or retake, the forts, as the case may require, at, and after the inauguration".[15]

Cabinet selection

Lincoln's inaugural cabinet consisted of seven positions, listed here based on department seniority;

|

William Seward

Lincoln began the process of constructing his cabinet on election night.[16] Buchanan, in selecting his cabinet, had excluded the sizeable Douglas wing of the Democratic Party, and the cabinet never operated efficiently. Lincoln attempted to reach out to every faction of his party with a special emphasis on balancing anti-slavery former Whigs with former free-soil Democrats. It seems clear that his goal was not to create a "War Cabinet" (because he did not expect war), but to create a cabinet that would unite the party.[17] Lincoln's eventual cabinet would include all of his main rivals for the Republican nomination. Lincoln did not shy away from surrounding himself with strong-minded men, even those whose credentials for office appeared to be much more impressive than his own.[18]

On November 21, Lincoln took the train to Chicago where he would meet, for the first time, the new Vice President-elect Hannibal Hamlin. In addition to numerous public events, Lincoln met privately with Hamlin, Trumbull, and Donn Piatt, an Ohio editor and politician, to discuss the cabinet, and followed up with private meetings with just Hamlin.[19]

William Seward had been Lincoln's chief political rival, and on December 8 Lincoln offered him the position of Secretary of State. Seward was both the best known and the most powerful Republican, and his association with the administration was seen as essential to achieving party unity. In the early 1850s Seward had built a reputation as a radical on the slavery issue, but by 1860 he was considered a centrist.[20]

There was a delay in publicly announcing Seward's selection, and anti-Seward forces in New York exploited this delay to attack Seward's qualifications. Seward, unsure of whether he would be more effective inside or outside the new administration, sent Thurlow Weed to Springfield to get a feel for what influence Seward would have on Lincoln's decision-making. They met on December 20. Assured by Lincoln that Seward would have a proper role in the distribution of patronage, Seward accepted the post on December 28.[21] Seward would remain as Secretary of State for the duration of Lincoln's presidency and continue in that position under Andrew Johnson after Lincoln's assassination.[22]

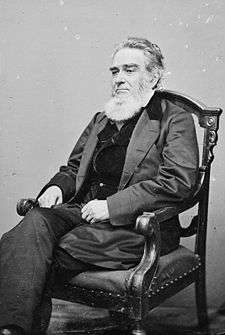

Salmon P. Chase

.jpg)

Lincoln contacted Seward's chief political rival, Salmon P. Chase of Ohio, and invited him to Springfield only after Seward had accepted the Secretary of State position. Chase was far more radical than either Lincoln or Seward, but this did not deter Lincoln. At their meeting on January 4 and 5, Lincoln was impressed with Chase, and they discussed the Secretary of Treasury position. The formal announcement, however, was not made until Lincoln was in Washington.[23] Seward and Weed opposed the selection of Chase because of both his strong antislavery record and his opposition to any type of settlement with the South that could be considered appeasement for slaveholders. They would lobby against Chase right up to Lincoln's inauguration. Chase, a former Democrat, was also opposed by Republican protectionists.[24] Chase would repeatedly threaten to resign to serve his own ends and finally Lincoln surprised him by accepting in 1864.[25] He would be replaced by William P. Fessenden. When he reluctantly took office, the economy was in dire straits. After a remarkable turn-around, Fesserden resigned only eight months later.[26] He was in turn replaced by Hugh McCulloch.[26]

Simon Cameron

The most problematic selection made by Lincoln was that of Simon Cameron as the Secretary of War. Cameron was one of the most influential public leaders in the crucial political state of Pennsylvania, but he was also alleged to be one of the most corrupt.[27] He was opposed within his own state by the faction led by Republican Governor-elect Andrew G. Curtin and Republican party chairman A. K. McClure. Cameron lieutenants went to Springfield two days after the election. They believed that Cameron had been promised a cabinet position at the Republican Convention and were surprised when they left Springfield without an offer from Lincoln. Lincoln carefully weighed the pros and cons of a Cameron appointment and met with Cameron in Springfield on December 28. Cameron returned to Pennsylvania with a letter from Lincoln stating that he would offer him either the Secretary of the Treasury or the Secretary of War. The letter was soon leaked to the press.[28]

However, very shortly after Cameron left Springfield, Lincoln began to receive negative reports from across the country regarding Cameron's selection. McClure sent a long letter to Lincoln protesting his consideration of Cameron and, at Lincoln's invitation, met with the president-elect in Springfield on January 3, 1861 and presented Lincoln with documentation that disqualified Cameron from office. Lincoln, admitting his mistake, wrote to Cameron that "things have developed which make it impossible for me to take you into the cabinet."[29] Lincoln offered Cameron the face-saving option of immediately and publicly declining the cabinet offers, assuring Cameron that "No person living knows, or has an intimation that I write this letter."[30] Cameron did not reply to Lincoln but told Trumbull that he would not decline, leaving the onus on Lincoln.[30]

Lobbying with Lincoln continued from all sides. He finally decided in early February that no decision would be made until he arrived in Washington. Once he did arrive, the competing factions realized that it was important to business interests that at least some Pennsylvanian be in Lincoln's cabinet. Cameron was then finally made Secretary of War.[31] Historian William Gienapp believed that the final selection of Cameron for this soon-to-be-critical position was a clear indicator that Lincoln did not anticipate a civil war.[32] Cameron would resign early the next year in 1862, amid corruption allegations.[33] He was replaced by Edwin Stanton.[34]

Edward Bates and Montgomery Blair, the search for southerners

Lincoln had discussed with Weed the possibility of nominating a southerner to the cabinet. On December 15, Lincoln did meet with Edward Bates of Missouri. Bates, a former conservative Whig, had been one of Lincoln's rivals for the presidential nomination. He accepted Lincoln's offer of Attorney-General. Bates said that he had declined a similar offer from Millard Fillmore in 1850, but the gravity of present events mandated that he accept. Lincoln requested that Bates devote some time to researching the legal and constitutional issues involving secession and southern efforts to censor the public mails. Bates' nomination was made public on December 21.[35] Bates would resign in 1864 after several disagreements with Lincoln, culminating in his resentment at not being nominated to the Supreme Court.[36] He was replaced by James Speed.[37]

Lincoln mentioned Montgomery Blair, and Weed countered with Henry Winter Davis of Baltimore or John A. Gilmer of North Carolina. John Minor Botts of Virginia also came up when the subject moved to having even a second Border or Southern representative. Lincoln followed up on the Gilmer suggestion by requesting that he come to Springfield; however Gilmer declined the visit and later declined a direct offer of a cabinet post offered in person by Seward. Southerners William A. Graham of North Carolina and James Guthrie of Kentucky also rejected feelers sent out by Lincoln. Longtime friend Joshua Speed from Kentucky may also have been considered.[38]

Montgomery Blair came from the best known political family in the North, if not the entire country. His father, Francis P. Blair, started the legacy when he was a close and influential advisor for President Andrew Jackson.[39] As a Marylander, Lincoln felt Blair's addition would help to keep the Border States and Upper South from seceding. Blair was Lincoln's final choice for Postmaster General.[40] Blair was asked to resign in 1864[41] and replaced by William Dennison.[42]

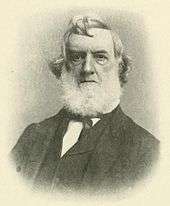

Gideon Welles

Gideon Welles of Connecticut was a former Jacksonian Democrat who had served in the Navy Department under President James K. Polk. Lincoln had delegated the selection of the New England position in his cabinet to Vice-president-elect Hamlin. At his meetings with Hamlin in Chicago, Lincoln asked him to co-ordinate his decision with Seward, but in addition to Welles the names of Charles Francis Adams, Nathaniel P. Banks, and Amos Tuck were considered. Adams was eliminated when Lincoln decided in December that a New Englander with a Democratic past was a better political fit. Tuck had less ambitious goals than the cabinet, and recommended Welles. Banks fell out of consideration for geographical reasons since prior to the election he had moved to Illinois to accept the presidency of the Illinois Central Railroad. Hamlin's recommendation, the recommendations of other influential Republicans, and Lincoln's favorable impression when he had met Welles in Hartford earlier in the year, led to his selection as Secretary of the Navy.[43] Welles would serve the entire duration of Lincoln's presidency, and continue as Navy Secretary with Andrew Johnson.[44]

Caleb Blood Smith

Caleb Blood Smith of Indiana was a former Whig representing the same type of midwestern constituency as Lincoln. His critics faulted him for some of his railroad ventures, accused him of being a Doughface, and questioned his intellectual capacity for a high government position. Among those who did support Smith were Weed and Seward, as well as close Lincoln advisor David Davis. In the end, Smith's selection for Secretary of the Interior had much to do with his campaign efforts on behalf of Lincoln and their friendship.[45] Smith would only serve about twenty months before resigning due to poor health.[46] He was replaced by John Palmer Usher.[46]

Compromise efforts

Initial efforts to compromise with, or appease, the South came from the Northern business community. Republican newspaper editors in New York, including Henry J. Raymond, James Webb, and Thurlow Weed, proposed a variety of measures in November including compensation for fugitive slaves, the repeal of personal liberty laws, and restoration of the Missouri Compromise line. Lincoln's reaction was astonishment at the fact that "any Republican think, for a moment, of abandoning in the hour of victory, though in the face of danger, every point involved in the recent contest."[47] Journalist Henry Villard dismissed the editors' reaction as merely "certain pangs of contrition" being felt by Wall Street as markets reacted negatively to Southern secession.[48]

In December the focus on compromise moved to Washington. In the House of Representatives a committee of 33 was formed, while in the Senate a committee of 13 was established. Lincoln communicated with various Congressmen that there was room for negotiation on issues such as fugitive slaves, slavery in the District of Columbia, the domestic slave trade, and other issues related to slavery. However he made it clear that he was unalterably opposed to anything which would allow the expansion of slavery into any new states. In 1854, Lincoln indicated he would have been satisfied with simply extending the Missouri Compromise line to the Pacific coast, but since then he had seen the aggressiveness by southerners to pursue territory in Cuba and Latin America in order to create more land for slaves.[49]

On December 6, Lincoln wrote to Congressman Kellogg, on the House committee, that he should: "entertain no proposition for a compromise in regard to the extension of slavery. The instant you do, they have us under again; all our labor is lost, and sooner or later must be done over. Douglas is sure to be again trying to bring in his 'Pop. Sov.' Have none of it. The tug has to come & better now than later."[50] On December 10 he wrote to Senator Trumbull in virtually identical terms.[51]

When the Senate committee was considering the specifics of the Crittenden Compromise, Lincoln was under considerable pressure to accept it. Seward sent Weed to Springfield to lobby Lincoln directly. Lincoln resisted this and other overtures. The proposed compromise re-established the old Missouri Compromise line, creating the possibility of new slave states. This was the issue where Lincoln would stand firm.[52]

Travel to Washington

On February 11, Lincoln boarded a special train that over the course of the next two weeks would take the President-elect to the nation's capital. Speaking to the crowd at the Springfield station, Lincoln bid farewell to his friends and supporters.

My friends -- No one, not in my situation, can appreciate my feeling of sadness at this parting. To this place, and the kindness of these people, I owe everything. Here I have lived a quarter of a century, and have passed from a young man to an old man. ...I now leave, not knowing when, or whether ever, I may return, with a task before me greater than that which rested upon Washington. Without the assistance of the Divine Being, who ever attended him, I cannot succeed. ... Trusting in Him ... let us confidently hope that all will yet be well. To His care commending you, as I hope in your prayers you will commend me, I bid you an affectionate farewell.[53]

All of the major cities on the route scheduled receptions and formal public appearances. His speeches were mostly extemporaneous. Among his more eloquent efforts was a speech in Philadelphia's Independence Hall where he said:

I have never had a feeling politically that did not spring from the Declaration of Independence. . . It was not the mere matter of the separation of the colonies from the motherland; but something in that Declaration giving liberty, not alone to the people of this country, but hope to the world for all future time. It was that which gave promise that in due time, the weights should be lifted from the shoulders of all men, and that all should have an equal chance.[54]

Equally impressively, he discussed George Washington and the legacy of the Revolution in Trenton before the New Jersey legislature:

I remember all the accounts there [in Weem's "Life of Washington"] given of the battle fields and struggles for the liberties of the country, and none fixed themselves upon my imagination so deeply as the struggle here at Trenton, New-Jersey. The crossing of the river; the contest with the Hessians; the great hardships endured at that time, all fixed themselves on my memory more than any single revolutionary event; and you all know, for you have all been boys, how these early impressions last longer than any others. I recollect thinking then, boy even though I was, that there must have been something more than common that those men struggled for; that something even more than National Independence; that something that held out a great promise to all the people of the world to all time to come; I am exceedingly anxious that this Union, the Constitution, and the liberties of the people shall be perpetuated in accordance with the original idea for which that struggle was made, and I shall be most happy indeed if I shall be an humble instrument in the hands of the Almighty, and of this, his almost chosen people, for perpetuating the object of that great struggle.[55]

In the main Lincoln carried a message that he had no hostile intentions towards the South, that disunion was not acceptable, and he intended to enforce the laws and protect property.[56]

Baltimore Plot

There was no U.S. Secret Service yet then in Lincoln's day. His entire official security for the trip consisted of four U.S. Army officers. Samuel M. Felton, the president of the Philadelphia, Wilmington & Baltimore Railroad, (P.W. & B.) had hired detective Allan Pinkerton to investigate reports that secessionists might try to sabotage the railroad along Lincoln's route. In conducting his investigation Pinkerton obtained information that indicated to him that an attempt to assassinate President-elect Lincoln would occur in Baltimore. Lincoln first learned of the plot on the evening of February 21 in his Philadelphia hotel room when he met with Pinkerton and Felton.[57]

In Baltimore, Lincoln would be required to change trains by moving from one railway station to another (as all passengers and cargo/freight, as by city ordinance, steam-powered locomotives were not allowed within the city due to fire hazards since the 1830s - passengers walked, used a horse or carriage/wagon or the line's rail cars were pulled through the downtown by horse on street rails). Pinkerton said that when Lincoln arrived directly from Harrisburg, Pennsylvania to Baltimore at the Calvert Street Station or the Bolton Station of the Northern Central Railroad, a gang of armed secessionists would stage a diversion to distract the newly reorganized city police, giving designated assassins an opportunity to kill an unguarded Lincoln.[58] Pinkerton tried to convince Lincoln to cancel his stop at Harrisburg, Pennsylvania and to proceed secretly straight through Baltimore. Lincoln said he intended to raise the American flag in a ceremony at Philadelphia's historic Old State House (now known as Independence Hall) the next day and then fulfill his public commitments in Harrisburg to address the Pennsylvania General Assembly at the State Capitol. After that he would agree to go with Pinkerton.[59]

Lincoln was also visited that night by Frederick Seward, the son of William Seward, his newly nominated Secretary of State. A separate investigation initiated by General-in-Chief Winfield Scott had produced independent and corroborating evidence of a specific threat to Lincoln in Baltimore. The New York detectives that conducted this investigation wrote that "there is serious danger of violence to and the assassination of Mr. Lincoln in his passage through that city [Baltimore] should the time of passage be known." The detectives had heard "men declare that if Mr. Lincoln was to be assassinated they would like to be the men."[60]

Lincoln did attend the Philadelphia and Harrisburg events before the crowds of spectators and the legislators, then secretly leaving Harrisburg on the evening of February 22, heading east in a special car attached to the end of a fast express back to Philadelphia, switched trains and lines to board a rear sleeping car on Felton's line, the P. W. & B., then heading southwest. Arriving in the middle of the night in the city of southern sympathizers in Maryland, passing between Baltimore's two downtown waterfront rail depots from the President Street Station (of the P.W. & B.) on the east side of the harbor and the Camden Street Station of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, on the southwestern side and then being pulled by horse-drawn cars (steam-powered locomotives not then allowed within city limits by municipal ordinance) along President, Pratt and Howard Streets, facing the piers of "The Basin" (today's Inner Harbor), arriving in the nation's capital safely at the B. & O. rail depot the following morning of the 23rd. He was accompanied only by his friend Ward Hill Lamon, Pinkerton, and a railroad superintendent. It is also thought that another railroad detective also distantly observed and accompanied them unknown to the important political passengers. Lincoln was dressed in an overcoat, muffler, and soft wool hat, and probably slept in his berth through the entire time that the cars were pulled through Baltimore's waterfront at around 3 o'clock in the early morning. The unannounced departure from the published schedule as well as the unconventional (for Lincoln) dress led to critics and cartoonists accusing him of sneaking into Washington in disguise (such as wearing a plaid Scotch cap and shawl). The later public controversy and supposed humiliation was embarrassing both to Lincoln and to his supporters.[61]

Lincoln takes office

Inauguration

Lincoln was aware that his inaugural address would be delivered in conditions that no other president had ever faced. He had started preparing it two weeks before he left Springfield but was aware that the political landscape was rapidly changing, possibly requiring changes in the speech up to the day of delivery. He departed from his normal speech-writing pattern by inviting others to comment on it while he was still writing it. Orville Browning had been given a copy during the trip to Washington, and Lincoln followed his advice to omit the overly aggressive phrase "to reclaim the public property and places which have fallen". Seward presented Lincoln with a six-page line-by-line written analysis of the speech, and Lincoln incorporated twenty-seven of Seward's specific recommendations.[62]

The March 4 Inauguration day started out as overcast, but by noon the sun had broken through the clouds. Security at the Capitol Building, where his address would be delivered, was heavy. Two thousand volunteer soldiers organized by Colonel Charles P. Stone, 653 regular troops, and marines were on duty supplemented by local police, cavalry patrolling the streets, and sharpshooters located on the tops of buildings. Plain clothes detectives moved through the crowd that had started assembling at dawn. Lincoln, accompanied by the departing President Buchanan, arrived by carriage at the Capitol at 1:15 p.m. The crowd in the streets and on the Capitol grounds was around 40,000.[63]

Lincoln was introduced to the crowd by his long-time friend, Oregon Senator Edward D. Baker. Lincoln's inaugural address began by attempting to reassure the South that he had no intention or constitutional authority to interfere with slavery in the southern states. He promised to enforce the fugitive slave laws and spoke favorably about a pending constitutional amendment that would preserve slavery in the states where it currently existed.[64]

After these assurances, however, Lincoln declared that secession was "the essence of anarchy" and it was his duty to "hold, occupy, and possess the property belonging to the government".[65] Focusing on those within the South who were still on the fence regarding secession, Lincoln contrasted "persons in one section or another who seek to destroy the Union as it exists" versus "those, however, who really love the Union".[66] In his closing remarks he spoke directly to the secessionists and emphasized the moral commitment that he was undertaking.[67]

The government will not assail you. You can have no conflict, without being yourselves the aggressors. You have no oath registered in Heaven to destroy the government, while I shall have the most solemn one to "preserve, protect, and defend it".I am loath to close. We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained, it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battle-field, and patriot grave, to every living heart and hearth-stone, all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.[68]

Chief Justice Roger Taney swore Lincoln in after the address. That evening there was an inaugural ball held in a specially built pavilion able to hold 2,500 people.[69]

Fighting begins: 1861–1862

Fort Sumter

As Lincoln assumed office an informal, uneasy truce had lasted for several months. Seven Deep South states had declared their secession, and the Union held, in the territory claimed by the new Confederate States of America, only Fort Sumter, Fort Pickens near Pensacola, Florida, and a couple of small forts in the Florida Keys. Any thoughts Lincoln might have had about using time to his advantage in addressing the crisis were shattered on March 5, the day after the inauguration, when he read a letter from Major Robert Anderson, the commander at Fort Sumter, stating that his troops would run out of provisions within four to six weeks.[70]

On March 3 General Scott had written to Seward suggesting that Fort Sumter be abandoned. Scott saw four options for the administration—a full-scale military operation to subdue the South, endorsement of the Crittenden Compromise to win back the seceded states, the closure of southern ports and the collection of duties from ships stationed outside the harbors, or directing the seven southern states that had declared secession to "depart in peace".[71]

Lincoln concentrated on the most immediate question of whether to maintain or abandon Fort Sumter. At a meeting on March 7, Scott and John G. Totten, the army's chief engineer, said that simply reinforcing the fort was not possible, although Welles and his top assistant Silas Stringham disagreed. Scott advised Lincoln that it would take a large fleet, 25,000 troops, and several months of training in order to defend the fort. On March 13 Montgomery Blair, the strongest proponent in the cabinet for standing firm at Fort Sumter, introduced Lincoln to his brother-in-law, Gustavus V. Fox. Fox presented a plan for a naval resupply and reinforcement of the fort. The plan had been approved by Scott during the last month of the previous administration, but Buchanan had rejected it. Scott had earlier advised Lincoln that it was too late for the plan to be successful, but the President was receptive to the proposed mission.[73]

The Fox proposal was discussed at a cabinet meeting, and Lincoln followed up on March 15 by asking each cabinet member to provide a written answer to the question, "Assuming it to be possible to now provision Fort-Sumpter [sic], under all circumstances, is it wise to attempt it?" Only Blair gave his unconditional approval to the plan. No decision was reached, although Lincoln told at least one congressman that if he were forced to surrender Sumter, holding Fort Pickens would still make a symbolic point. In the meantime Lincoln personally dispatched Fox to Charleston to talk to Anderson and independently assess the situation. Lincoln also sent Illinois friends Stephen A. Hurlbut and Ward Lamon to the city on a separate intelligence-gathering mission. The recommendations that came back were that reinforcement was both necessary, since secessionist feeling ran high and threatened the fort, and feasible, despite Anderson's misgivings.[74]

On March 28, however, Scott recommended that both Pickens and Sumter be abandoned, basing his decision more on political than military grounds. The next day a deeply agitated Lincoln presented Scott's proposal to the cabinet. Blair was now joined by Welles and Chase in supporting reinforcement. Bates was non-committal, Cameron was not in attendance, and Seward and Smith opposed resupply. Later that day Lincoln gave Fox the order to begin assembling a squadron to reinforce Fort Sumter.[75]

The actual dispatch of the squadron was complicated by the failure of Lincoln, Welles, Seward, and the men on the ground preparing the expedition to communicate effectively. Assets needed for the Fort Sumter expedition were mistakenly directed to a separate mission to Fort Pickens, a mission that was plagued by faulty communication between Washington and the forces already in Florida.[76] On April 6, with the Sumter mission ready to go, Lincoln sent State Department clerk Robert S. Chew to see South Carolina Governor Francis W. Pickens and read the following statement:

I am directed by the President of the United States to notify you to expect an attempt will be made to supply Fort-Sumpter [sic] with provisions only; and that, if such attempt be not resisted, no effort to throw in men, arms, or ammunition, will be made, without further notice, or in case of an attack upon the Fort.[77]

The message was delivered to Pickens on April 8.[78] The information was telegraphed that night to Confederate President Jefferson Davis in Richmond. The Confederate cabinet was already meeting to discuss the Sumter crisis, and on April 10 Davis decided to demand the surrender of the fort and bombard it if the demand was refused.[79] The attack on the fort was initiated on April 12, and the fort surrendered the next day. The relief expedition sent by the Union arrived too late to intervene. The Civil War had begun.

Assuming command for the Union in the war

After the Battle of Fort Sumter, Lincoln realized the importance of taking immediate executive control of the war and making an overall strategy to put down the rebellion. Lincoln encountered an unprecedented political and military crisis, and he responded as commander-in-chief, using unprecedented powers. He expanded his war powers, and imposed a blockade on all the Confederate shipping ports, disbursed funds before appropriation by Congress, and after suspending habeas corpus, arrested and imprisoned thousands of suspected Confederate sympathizers. Lincoln was supported by Congress and the northern public for these actions. In addition, Lincoln had to contend with reinforcing strong Union sympathies in the border slave states and keeping the war from becoming an international conflict.[80]

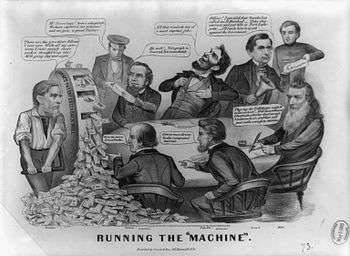

The war effort was the source of continued disparagement of Lincoln, and dominated his time and attention. From the start, it was clear that bipartisan support would be essential to success in the war effort, and any manner of compromise alienated factions on both sides of the aisle, such as the appointment of Republicans and Democrats to command positions in the Union Army. Copperheads criticized Lincoln for refusing to compromise on the slavery issue. Conversely, the Radical Republicans criticized him for moving too slowly in abolishing slavery.[81] On August 6, 1861, Lincoln signed the Confiscation Act that authorized judiciary proceedings to confiscate and free slaves who were used to support the Confederate war effort. In practice, the law had little effect, but it did signal political support for abolishing slavery in the Confederacy.[82]

In late August 1861, General John C. Frémont, the 1856 Republican presidential nominee, issued, without consulting his superiors in Washington, a proclamation of martial law in Missouri. He declared that any citizen found bearing arms could be court-martialed and shot, and that slaves of persons aiding the rebellion would be freed. Frémont was already under a cloud with charges of negligence in his command of the Department of the West compounded with allegations of fraud and corruption. Lincoln overruled Frémont's proclamation. Lincoln believed that Fremont's emancipation was political; neither militarily necessary nor legal.[83] After Lincoln acted, Union enlistments from Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri increased by over 40,000 troops.[84]

Lincoln left most diplomatic matters to his Secretary of State, William Seward. At times Seward was too bellicose, so for balance Lincoln stuck a close working relationship with Senator Charles Sumner, the chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee.[85] The Trent Affair of late 1861 threatened war with Great Britain. The U.S. Navy had illegally intercepted a British mail ship, the Trent, on the high seas and seized two Confederate envoys; Britain protested vehemently while the U.S. cheered. Lincoln ended the crisis by releasing the two diplomats. Biographer James G. Randall has dissected Lincoln's successful techniques:

- his restraint, his avoidance of any outward expression of truculence, his early softening of State Department's attitude toward Britain, his deference toward Seward and Sumner, his withholding of his own paper prepared for the occasion, his readiness to arbitrate, his golden silence in addressing Congress, his shrewdness in recognizing that war must be averted, and his clear perception that a point could be clinched for America's true position at the same time that full satisfaction was given to a friendly country.[86]

Lincoln painstakingly monitored the telegraphic reports coming into the War Department headquarters. He kept close tabs on all phases of the military effort, consulted with governors, and selected generals based on their past success (as well as their state and party). In January 1862, after many complaints of inefficiency and profiteering in the War Department, Lincoln replaced Simon Cameron with Edwin Stanton as War Secretary. Stanton was a staunchly Unionist pro-business conservative Democrat who moved toward the Radical Republican faction. Nevertheless, he worked more often and more closely with Lincoln than any other senior official. "Stanton and Lincoln virtually conducted the war together," say Thomas and Hyman.[87]

In terms of war strategy, Lincoln articulated two priorities: to ensure that Washington was well-defended, and to conduct an aggressive war effort that would satisfy the demand in the North for prompt, decisive victory; major Northern newspaper editors expected victory within 90 days.[88] Twice a week, Lincoln would meet with his cabinet in the afternoon, and occasionally Mary Lincoln would force him to take a carriage ride because she was concerned he was working too hard.[89] Lincoln learned from reading the theoretical book of his chief of staff General Henry Halleck, a disciple of the European strategist Jomini; he began to appreciate the critical need to control strategic points, such as the Mississippi River;.[90] Lincoln saw the importance of Vicksburg and understood the necessity of defeating the enemy's army, rather than simply capturing territory.[91]

General McClellan

After the Union defeat at the First Battle of Bull Run and the retirement of the aged Winfield Scott in late 1861, Lincoln appointed Major General George B. McClellan general-in-chief of all the Union armies.[92] McClellan, a young West Point graduate, railroad executive, and Pennsylvania Democrat, took several months to plan and attempt his Peninsula Campaign, longer than Lincoln wanted. The campaign's objective was to capture Richmond by moving the Army of the Potomac by boat to the peninsula and then overland to the Confederate capital. McClellan's repeated delays frustrated Lincoln and Congress, as did his position that no troops were needed to defend Washington. Lincoln insisted on holding some of McClellan's troops in defense of the capital; McClellan, who consistently overestimated the strength of Confederate troops, blamed this decision for the ultimate failure of the Peninsula Campaign.[93]

Lincoln removed McClellan as general-in-chief in March 1862, after McClellan's "Harrison's Landing Letter", in which he offered unsolicited political advice to Lincoln urging caution in the war effort.[94] The office remained empty until July, when Henry Halleck was selected for it.[95] McClellan's letter incensed Radical Republicans, who successfully pressured Lincoln to appoint John Pope, a Republican, as head of the new Army of Virginia. Pope complied with Lincoln's strategic desire to move toward Richmond from the north, thus protecting the capital from attack.[96]

However, lacking requested reinforcements from McClellan, now commanding the Army of the Potomac, Pope was soundly defeated at the Second Battle of Bull Run in the summer of 1862, forcing the Army of the Potomac to defend Washington for a second time.[96] The war also expanded with naval operations in 1862 when the CSS Virginia, formerly the USS Merrimack, damaged or destroyed three Union vessels in Norfolk, Virginia, before being engaged and damaged by the USS Monitor. Lincoln closely reviewed the dispatches and interrogated naval officers during their clash in the Battle of Hampton Roads.[97]

Despite his dissatisfaction with McClellan's failure to reinforce Pope, Lincoln was desperate, and restored him to command of all forces around Washington, to the dismay of all in his cabinet but Seward.[98] Two days after McClellan's return to command, General Robert E. Lee's forces crossed the Potomac River into Maryland, leading to the Battle of Antietam in September 1862.[99] The ensuing Union victory was among the bloodiest in American history, but it enabled Lincoln to announce that he would issue an Emancipation Proclamation in January. Having composed the Proclamation some time earlier, Lincoln had waited for a military victory to publish it to avoid it being perceived as the product of desperation.[100]

McClellan then resisted the President's demand that he pursue Lee's retreating and exposed army, while his counterpart General Don Carlos Buell likewise refused orders to move the Army of the Ohio against rebel forces in eastern Tennessee. As a result, Lincoln replaced Buell with William Rosecrans; and, after the 1862 midterm elections, he replaced McClellan with Republican Ambrose Burnside. Both of these replacements were political moderates and prospectively more supportive of the Commander-in-Chief.[101]

.jpg)

Burnside, against the advice of the president, prematurely launched an offensive across the Rappahannock River and was stunningly defeated by Lee at Fredericksburg in December. Not only had Burnside been defeated on the battlefield, but his soldiers were disgruntled and undisciplined. Desertions during 1863 were in the thousands and they increased after Fredericksburg.[102] Lincoln brought in Joseph Hooker, despite his record of loose talk about the need for a military dictatorship.[103]

The mid-term elections in 1862 brought the Republicans severe losses due to sharp disfavor with the administration over its failure to deliver a speedy end to the war, as well as rising inflation, new high taxes, rumors of corruption, the suspension of habeas corpus, the military draft law, and fears that freed slaves would undermine the labor market. The Emancipation Proclamation announced in September gained votes for the Republicans in the rural areas of New England and the upper Midwest, but it lost votes in the cities and the lower Midwest.[104]

While Republicans were discouraged, Democrats were energized and did especially well in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, and New York. The Republicans did maintain their majorities in Congress and in the major states, except New York. The Cincinnati Gazette contended that the voters were "depressed by the interminable nature of this war, as so far conducted, and by the rapid exhaustion of the national resources without progress".[104]

In the spring of 1863, Lincoln was optimistic about upcoming military campaigns to the point of thinking the end of the war could be near if a string of victories could be put together; these plans included Hooker's attack on Lee north of Richmond, Rosecrans' on Chattanooga, Grant's on Vicksburg, and a naval assault on Charleston.[105]

Hooker was routed by Lee at the Battle of Chancellorsville in May,[106] but continued to command his troops for some weeks. He ignored Lincoln's order to divide his troops, and possibly force Lee to do the same in Harper's Ferry, and tendered his resignation, which Lincoln accepted. He was replaced by George Meade, who followed Lee into Pennsylvania for the Gettysburg Campaign, which was a victory for the Union, though Lee's army avoided capture. At the same time, after initial setbacks, Grant laid siege to Vicksburg and the Union navy attained some success in Charleston harbor.[107] After the Battle of Gettysburg, Lincoln clearly understood that his military decisions would be more effectively carried out by conveying his orders through his War Secretary or his general-in-chief on to his generals, who resented his civilian interference with their own plans. Even so, he often continued to give detailed directions to his generals as Commander-in-Chief.[108]

Fighting continues 1862-1865

Emancipation Proclamation

Congress in July 1862 moved to free the slaves by passing the Confiscation Act of 1862. The goal was to weaken the rebellion, which was led and controlled by slave owners. This did not abolish the legal institution of slavery (the 13th Amendment did that), but it shows Lincoln had the support of Congress in liberating the slaves owned by rebels. Lincoln implemented the new law by his "Emancipation Proclamation."

Lincoln is well known for ending slavery in the United States. However, throughout 1861–62, Lincoln made it clear that the North was fighting the war to preserve the Union. Freeing the slaves became, in late 1862, a war measure to weaken the rebellion by destroying the economic base of its leadership class. Abolitionists criticized Lincoln for his slowness, but on August 22, 1862, Lincoln explained:

I would save the Union. I would save it the shortest way under the Constitution. The sooner the national authority can be restored; the nearer the Union will be "the Union as it was". ... My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that.[109]

The Emancipation Proclamation, announced on September 22 and put in effect January 1, 1863, freed slaves in territories not under Union control. As Union armies advanced south, more slaves were liberated until all of them in Confederate hands were freed (over three million). Lincoln later said: "I never, in my life, felt more certain that I was doing right, than I do in signing this paper". The proclamation made abolishing slavery in the rebel states an official war goal. Lincoln then threw his energies into passage of the 13th Amendment to permanently abolish slavery throughout the nation.[110]

Lincoln had for some time been working on plans to set up colonies for the newly freed slaves. He remarked upon colonization favorably in the Emancipation Proclamation, but all attempts at such a massive undertaking failed. As Frederick Douglass observed, Lincoln was, "The first great man that I talked with in the United States freely who in no single instance reminded me of the difference between himself and myself, of the difference of color".[111]

Gettysburg Address

The Battle of Gettysburg was one of the bloodiest battles of the War, ending with almost 50,000 casualties. Abraham Lincoln was invited to come to Gettysburg to dedicate the first national cemetery and honor the soldiers who had fallen. His Gettysburg address became a core statement of American political values. Lincoln's carefully crafted address, secondary to other presentations that day, was one of the greatest and most influential statements of national purpose. In just over two minutes, Lincoln reiterated the principles of human equality espoused by the Declaration of Independence and proclaimed the Civil War as a struggle for the preservation of the Union with "a new birth of freedom"[112] that would bring true equality to all of its people. Winning the war, he said, was essential to prove to the world that democracy was a viable form of government. Repeatedly he mentioned the themes of death for a great cause, the memory of the dead, and the rebirth of a new nation based on freedom.

The Gettysburg address is one of the most important speeches in American History. In it Lincoln redefined the national purpose in terms of unity, democracy and equality.

General Grant

Meade's failure to capture Lee's army as it retreated from Gettysburg, and the continued passivity of the Army of the Potomac, persuaded Lincoln that a change in command was needed. General Ulysses S. Grant's victories at the Battle of Shiloh and in the Vicksburg campaign impressed Lincoln and made Grant a strong candidate to head the Union Army. Responding to criticism of Grant after Shiloh, Lincoln had said, "I can't spare this man. He fights."[113] With Grant in command, Lincoln felt the Union Army could relentlessly pursue a series of coordinated offensives in multiple theaters, and have a top commander who agreed on the use of black troops.[114]

Nevertheless, Lincoln was concerned that Grant might be considering a candidacy for President in 1864, as McClellan was. Lincoln arranged for an intermediary to make inquiry into Grant's political intentions, and being assured that he had none, submitted to the Senate Grant's promotion to commander of the Union Army. He obtained Congress's consent to reinstate for Grant the rank of Lieutenant General, which no officer had held since George Washington.[115]

Grant waged his bloody Overland Campaign in 1864. This is often characterized as a war of attrition, given high Union losses at battles such as the Battle of the Wilderness and Cold Harbor. Even though they had the advantage of fighting on the defensive, the Confederate forces had "almost as high a percentage of casualties as the Union forces".[116] The high casualty figures of the Union alarmed the North; Grant had lost a third of his army, and Lincoln asked what Grant's plans were, to which the general replied, "I propose to fight it out on this line if it takes all summer."[117]

The Confederacy lacked reinforcements, so Lee's army shrank with every costly battle. Grant's army moved south, crossed the James River, forcing a siege and trench warfare outside Petersburg, Virginia. Lincoln then made an extended visit to Grant's headquarters at City Point, Virginia. This allowed the president to confer in person with Grant and William Tecumseh Sherman about the hostilities, as Sherman coincidentally managed a hasty visit to Grant from his position in North Carolina.[118] Lincoln and the Republican Party mobilized support for the draft throughout the North, and replaced the Union losses.[119]

Lincoln authorized Grant to target the Confederate infrastructure—such as plantations, railroads, and bridges—hoping to destroy the South's morale and weaken its economic ability to continue fighting. Grant's move to Petersburg resulted in the obstruction of three railroads between Richmond and the South. This strategy allowed Generals Sherman and Philip Sheridan to destroy plantations and towns in Virginia's Shenandoah Valley. The damage caused by Sherman's March to the Sea through Georgia in 1864 was limited to a 60-mile (97 km) swath, but neither Lincoln nor his commanders saw destruction as the main goal, but rather defeat of the Confederate armies. Mark E. Neely Jr. has argued that there was no effort to engage in "total war" against civilians which he believed did take place during World War II.[120]

Confederate general Jubal Early began a series of assaults in the North that threatened the Capital. During Early's raid on Washington, D.C. in 1864, Lincoln was watching the combat from an exposed position; Captain Oliver Wendell Holmes shouted at him, "Get down, you damn fool, before you get shot!"[121] After repeated calls on Grant to defend Washington, Sheridan was appointed and the threat from Early was dispatched.[122]

As Grant continued to wear down Lee's forces, efforts to discuss peace began. Confederate Vice President Stephens led a group to meet with Lincoln, Seward, and others at Hampton Roads. Lincoln refused to allow any negotiation with the Confederacy as a coequal; his sole objective was an agreement to end the fighting and the meetings produced no results.[123] On April 1, 1865, Grant successfully outflanked Lee's forces in the Battle of Five Forks and nearly encircled Petersburg, and the Confederate government evacuated Richmond. Days later, when that city fell, Lincoln visited the vanquished Confederate capital; as he walked through the city, white Southerners were stone-faced, but freedmen greeted him as a hero. On April 9, Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox and the war was effectively over.[124]

Domestic measures

Lincoln adhered to the Whig theory of the presidency, which gave Congress primary responsibility for writing the laws while the Executive enforced them. Lincoln vetoed only four bills passed by Congress; the only important one was the Wade-Davis Bill with its harsh program of Reconstruction.[125] He signed the Homestead Act in 1862, making millions of acres of government-held land in the West available for purchase at very low cost. The Morrill Land-Grant Colleges Act, also signed in 1862, provided government grants for agricultural colleges in each state. The Pacific Railway Acts of 1862 and 1864 granted federal support for the construction of the United States' First Transcontinental Railroad, which was completed in 1869.[126] The passage of the Homestead Act and the Pacific Railway Acts was made possible by the absence of Southern congressmen and senators who had opposed the measures in the 1850s.[127]

| The Lincoln Cabinet[128] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Office | Name | Term |

| President | Abraham Lincoln | 1861–1865 |

| Vice President | Hannibal Hamlin | 1861–1865 |

| Andrew Johnson | 1865 | |

| Secretary of State | William H. Seward | 1861–1865 |

| Secretary of Treasury | Salmon P. Chase | 1861–1864 |

| William P. Fessenden | 1864–1865 | |

| Hugh McCulloch | 1865 | |

| Secretary of War | Simon Cameron | 1861–1862 |

| Edwin M. Stanton | 1862–1865 | |

| Attorney General | Edward Bates | 1861–1864 |

| James Speed | 1864–1865 | |

| Postmaster General | Montgomery Blair | 1861–1864 |

| William Dennison Jr. | 1864–1865 | |

| Secretary of the Navy | Gideon Welles | 1861–1865 |

| Secretary of the Interior | Caleb Blood Smith | 1861–1862 |

| John Palmer Usher | 1863–1865 | |

Other important legislation involved two measures to raise revenues for the Federal government: tariffs (a policy with long precedent), and a new Federal income tax. In 1861, Lincoln signed the second and third Morrill Tariff, the first having become law under James Buchanan. Also in 1861, Lincoln signed the Revenue Act of 1861, creating the first U.S. income tax.[129] This created a flat tax of 3 percent on incomes above $800 ($21,100 in current dollar terms), which was later changed by the Revenue Act of 1862 to a progressive rate structure.[130]

Lincoln also presided over the expansion of the federal government's economic influence in several other areas. The creation of the system of national banks by the National Banking Act provided a strong financial network in the country. It also established a national currency. In 1862, Congress created, with Lincoln's approval, the Department of Agriculture.[131] In 1862, Lincoln sent a senior general, John Pope, to put down the "Sioux Uprising" in Minnesota. Presented with 303 execution warrants for convicted Santee Dakota who were accused of killing innocent farmers, Lincoln conducted his own personal review of each of these warrants, eventually approving 39 for execution (one was later reprieved).[132] President Lincoln had planned to reform federal Indian policy.[133]

In the wake of Grant's casualties in his campaign against Lee, Lincoln had considered yet another executive call for a military draft, but it was never issued. In response to rumors of one, however, the editors of the New York World and the Journal of Commerce published a false draft proclamation which created an opportunity for the editors and others employed at the publications to corner the gold market. Lincoln's reaction was to send the strongest of messages to the media about such behavior; he ordered the military to seize the two papers. The seizure lasted for two days.[134]

Lincoln is largely responsible for the institution of the Thanksgiving holiday in the United States.[135] Before Lincoln's presidency, Thanksgiving, while a regional holiday in New England since the 17th century, had been proclaimed by the federal government only sporadically and on irregular dates. The last such proclamation had been during James Madison's presidency 50 years before. In 1863, Lincoln declared the final Thursday in November of that year to be a day of Thanksgiving.[135] In June 1864, Lincoln approved the Yosemite Grant enacted by Congress, which provided unprecedented federal protection for the area now known as Yosemite National Park.[136]

1864 election and second inauguration

After Union victories at Gettysburg, Vicksburg and Chattanooga in 1863, victory seemed at hand. Lincoln promoted Ulysses S. Grant General-in-Chief on March 12, 1864. When the spring campaigns all turned into bloody stalemates, Lincoln strongly supported Grant's strategy of wearing down Lee's army at the cost of heavy Union casualties. "I can't spare this man." he said. "He fights." Lincoln easily defeated efforts to deny his renomination, and selected Andrew Johnson, a War Democrat from the Southern state of Tennessee as his running mate in order to form a broader coalition. They ran on the new Union Party ticket; it was a coalition of Republicans and War Democrats.

Republicans across the country had the jitters in August, fearing that Lincoln would be defeated. Acknowledging those fears, Lincoln wrote and signed a pledge that, if he should lose the election, he would nonetheless defeat the Confederacy by an all-out military effort before turning over the White House:[137]

This morning, as for some days past, it seems exceedingly probable that this Administration will not be re-elected. Then it will be my duty to so co-operate with the President elect, as to save the Union between the election and the inauguration; as he will have secured his election on such ground that he cannot possibly save it afterwards.[138]

Lincoln did not show the pledge to his cabinet, but asked them to sign the sealed envelope.

The Democratic platform followed the Peace wing of the party, calling the war a "failure". However, their candidate, General George McClellan, supported the war and repudiated the platform.

Lincoln provided Grant with new replacements and mobilized the Union party to support Grant and talk up local support for the war. Sherman's capture of Atlanta in September ended defeatist jitters; the Democratic Party was deeply split, with some leaders and most soldiers openly for Lincoln; the Union party was united and energized, and Lincoln was easily re-elected in a landslide. He won all but two states, capturing 212 of 233 electoral votes.

On March 4, 1865, he delivered his second inaugural address, which was his favorite of all his speeches. At this time, a victory over the rebels was at hand, slavery was dead, and Lincoln was looking to the future.

Fondly do we hope — fervently do we pray — that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue, until all the wealth piled by the bond-man's two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash, shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said "the judgments of the Lord, are true and righteous altogether." With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation's wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan — to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations.[139]

Foreign policy

Every nation was officially neutral throughout the American Civil War, and none recognized the Confederacy. That marked a major diplomatic achievement for Secretary Seward and the Lincoln Administration. France, under Napoleon III, had invaded Mexico and installed a puppet regime; it hoped to negate American influence. France therefore encouraged Britain in a policy of mediation suggesting that both would recognize the Confederacy.[140] Washington repeatedly warned that meant war. The British textile industry depended on cotton from the South, but it had stocks to keep the mills operating for a year and in any case the industrialists and workers carried little weight in British politics. Knowing a war would cut off vital shipments of American food, wreak havoc on the British merchant fleet, and cause the immediate loss of Canada, Britain, with its powerful Royal Navy, refused to go along.[141]

Lincoln's foreign policy was deficient in 1861 in terms of appealing to European public opinion. Diplomats had to explain that United States was not committed to the ending of slavery, but instead they repeated legalistic arguments about the unconstitutionality of secession. Confederate spokesman, on the other hand, were much more successful by ignoring slavery and instead focusing on their struggle for liberty, their commitment to free trade, and the essential role of cotton in the European economy. In addition, the European aristocracy (the dominant factor in every major country) was "absolutely gleeful in pronouncing the and American debacle as proof that the entire experiment in popular government had failed. European government leaders welcomed the fragmentation of the ascendant American Republic."[142]

Elite opinion in Britain tended to favor the Confederacy, while public opinion tended to favor the United States. Large scale trade continued in both directions with the United States, with the Americans shipping grain to Britain while Britain sent manufactured items and munitions. Immigration continued into the United States. British trade with the Confederacy was limited, with a trickle of cotton going to Britain and some munitions slipped in by numerous small blockade runners. The Confederate strategy for securing independence was largely based on the hope of military intervention by Britain and France, but Confederate diplomacy proved inept. With the announcement of the Emancipation Proclamation in September 1862, it became a war against slavery that most British supported.[143]

A serious diplomatic dispute with the United States erupted over the "Trent Affair" in late 1861. Public opinion in the Union called for war against Britain, but Lincoln gave in and sent back the diplomats his Navy had illegally seized.[144]

British financiers built and operated most of the blockade runners, spending hundreds of millions of pounds on them; but that was legal and not the cause of serious tension. They were staffed by sailors and officers on leave from the Royal Navy. When the U.S. Navy captured one of the fast blockade runners, it sold the ship and cargo as prize money for the American sailors, then released the crew.

A long-term issue was the British shipyard (John Laird and Sons) building two warships for the Confederacy, including the CSS Alabama,over vehement protests from the United States. The controversy was resolved after the Civil War in the form of the Alabama Claims, in which the United States finally was given $15.5 million in arbitration by an international tribunal for damages caused by British-built warships.[145]

In the end, these instances of British involvement neither shifted the outcome of the war nor provoked the United States into declaring war against Britain. The U.S. diplomatic mission headed by Minister Charles Francis Adams, Sr. proved much more successful than the Confederate missions, which were never officially recognized.[146]

Judicial appointments

Supreme Court appointments

- Noah Haynes Swayne – Served from 1862 to 1881, replaced John McLean

- Samuel Freeman Miller – Served from 1862 to 1890, replaced Peter Vivian Daniel

- David Davis – Served from 1862 to 1877, replaced John Archibald Campbell

- Stephen Johnson Field – Served from 1863 to 1897, appointed to a newly-created seat

- Salmon Portland Chase – Chief Justice. Served from 1864 to 1873, replaced Roger Taney

.jpg)

Lincoln's declared philosophy on court nominations was that "we cannot ask a man what he will do, and if we should, and he should answer us, we should despise him for it. Therefore we must take a man whose opinions are known."[135] Lincoln made five appointments to the United States Supreme Court. Noah Haynes Swayne, nominated January 21, 1862 and appointed January 24, 1862, was chosen as an anti-slavery lawyer who was committed to the Union. Samuel Freeman Miller, nominated and appointed on July 16, 1862, supported Lincoln in the 1860 election and was an avowed abolitionist. David Davis, Lincoln's campaign manager in 1860, nominated December 1, 1862 and appointed December 8, 1862, had also served as a judge in Lincoln's Illinois court circuit. Stephen Johnson Field, a previous California Supreme Court justice, was nominated March 6, 1863 and appointed March 10, 1863, and provided geographic balance, as well as political balance to the court as a Democrat. Field would eventually become the longest-serving Justice, though William O. Douglas has since surpassed his record. Finally, Lincoln's Treasury Secretary, Salmon P. Chase, was nominated as Chief Justice, and appointed the same day, on December 6, 1864. Lincoln believed Chase was an able jurist, would support Reconstruction legislation, and that his appointment united the Republican Party. Lincoln's appointees served on the Chase Court, the Waite Court, and the Fuller Court.[147]

Other judicial appointments

Lincoln appointed 32 federal judges, including four Associate Justices and one Chief Justice to the Supreme Court of the United States, and 27 judges to the United States district courts. Lincoln appointed no judges to the United States circuit courts during his time in office.[148][149]

Home front

Civil liberties suspended

During the Civil War, Lincoln appropriated powers no previous President had wielded: he used his war powers to proclaim a blockade, suspended the writ of habeas corpus, spent money without congressional authorization, and imprisoned 18,000 suspected Confederate sympathizers without trial. Nearly all of his actions, although vehemently denounced by the Copperheads, were subsequently upheld by Congress and the Courts.

Reconstruction

Reconstruction began during the war as Lincoln and his associates pondered the questions of how to reintegrate the Southern states back into the Union, and what to do with Confederate leaders and with the freed slaves. Lincoln was the leader of the "moderates" regarding Reconstruction policy, and usually was opposed by the Radical Republicans led by Thaddeus Stevens in the House and Charles Sumner and Benjamin Wade in the Senate (though he co-operated with those men on most other issues). Lincoln was determined to find a course that would reunite the nation as soon as possible and not permanently alienate the Southerners, and throughout the war Lincoln urged speedy elections under generous terms in areas behind Union lines. Critical decisions had to be made during the war, as state after state was reconquered. Of special importance were Tennessee, where Lincoln appointed Andrew Johnson as governor, and Louisiana, where Lincoln tried a plan that would restore the state when 10% of the voters agreed. The Radicals thought that policy was too lenient, and passed their own plan, the Wade-Davis Bill, in 1864. Lincoln vetoed Wade-Davis, and the Radicals retaliated by refusing to seat representatives elected from Louisiana, Arkansas, and Tennessee.[150]

On April 9, 1865, General Lee surrendered at Appomattox Court House in Virginia; the war was effectively over. The other rebel armies surrendered and there was no guerrilla warfare. Lincoln went to Richmond to make a public gesture of sitting at Jefferson Davis's own desk, symbolically saying to the nation that the President of the United States held authority over the entire land. He was greeted at the city as a conquering hero by freed slaves, whose sentiments were epitomized by one admirer's quote, "I know I am free for I have seen the face of Father Abraham and have felt him". When a general asked Lincoln how the defeated Confederates should be treated, Lincoln replied, "Let 'em up easy."[151]

Historian Eric Foner notes that no one knows what Lincoln would have done about Reconstruction, but argues that "Lincoln's ideas would undoubtedly have continued to evolve."[152] However, Foner also asserts that,

- "Unlike Sumner and other Radicals, Lincoln did not see Reconstruction as an opportunity for a sweeping political and social revolution beyond emancipation. He had long made clear his opposition to the confiscation and redistribution of land. He believed, as most Republicans did in April 1865, that the voting requirements should be determined by the states. He assumed that political control in the South would pass to white Unionists, reluctant secessionists, and forward-looking former Confederates. But time and again during the war, Lincoln, after initial opposition, and come to embrace positions first advanced by abolitionists and Radical Republicans..... Lincoln undoubtedly would have listened carefully to the outcry for further protection for the former slaves.... It is entirely plausible to imagine Lincoln and Congress agreeing on a Reconstruction policy that encompassed federal protection for basic civil rights plus limited black suffrage, along the lines Lincoln proposed just before his death." [153]

Lincoln biographers James G. Randall and Richard Current, according to David Lincove, argue that:

- It is likely that had he lived, Lincoln would have followed a policy similar to Johnson's, that he would have clashed with congressional Radicals, that he would have produced a better result for the freedmen than occurred, and that his political skills would have helped him avoid Johnson's mistakes.[154]

Assassination

The assassination of Abraham Lincoln, one of the last major events in the Civil War, took place on Good Friday, April 14, 1865, when the President was shot while attending a performance of Our American Cousin at Ford's Theatre with his wife and two guests. Lincoln died early the next morning.

Lincoln's assassin, actor and Confederate sympathizer John Wilkes Booth, had also plotted with fellow conspirators, Lewis Powell and George Atzerodt to kill William H. Seward (then Secretary of State) and Vice-President Andrew Johnson respectively. Booth hoped to create chaos and overthrow the Federal government by assassinating Lincoln, Seward, and Johnson. Although Booth succeeded in killing Lincoln, the larger plot failed. Seward was attacked, but recovered from his wounds, and Johnson's would-be assassin fled Washington upon losing his nerve.

Historical reputation

In surveys of U.S. scholars ranking presidents conducted since the 1940s, Lincoln is consistently ranked in the top three, often as number one.[155][156] A 2004 study found that scholars in the fields of history and politics ranked Lincoln number one, while legal scholars placed him second after Washington.[157] In presidential ranking polls conducted in the United States since 1948, Lincoln has been rated at the very top in the majority of polls: Schlesinger 1948, Schlesinger 1962, 1982 Murray Blessing Survey, Chicago Tribune 1982 poll, Schlesinger 1996, CSPAN 1996, Ridings-McIver 1996, Time 2008, and CSPAN 2009. Generally, the top three presidents are rated as 1. Lincoln; 2. George Washington; and 3. Franklin D. Roosevelt, although Lincoln and Washington, and Washington and Roosevelt, are occasionally reversed.[158]

President Lincoln's assassination increased his status to the point of making him a national martyr. Lincoln was viewed by abolitionists as a champion for human liberty. Republicans linked Lincoln's name to their party. Many, though not all, in the South considered Lincoln as a man of outstanding ability.[159]

Schwartz argues that Lincoln's reputation grew slowly in the late 19th century until the Progressive Era (1900–1920s) when he emerged as one of the most venerated heroes in American history, with even white Southerners in agreement. The high point came in 1922 with the dedication of the Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall in Washington, D.C.[160] In the New Deal era liberals honored Lincoln not so much as the self-made man or the great war president, but as the advocate of the common man who they believe would have supported the welfare state. In the Cold War years, Lincoln's image shifted to emphasize the symbol of freedom who brought hope to those oppressed by communist regimes.[161]

By the 1970s Lincoln had become a hero to political conservatives[162] for his intense nationalism, support for business, his insistence on stopping the spread of human bondage, his acting in terms of Lockean and Burkean principles on behalf of both liberty and tradition, and his devotion to the principles of the Founding Fathers.[163][164][165] As a Whig activist, Lincoln was a spokesman for business interests, favoring high tariffs, banks, internal improvements, and railroads in opposition to the agrarian Democrats.[166] William C. Harris found that Lincoln's "reverence for the Founding Fathers, the Constitution, the laws under it, and the preservation of the Republic and its institutions undergirded and strengthened his conservatism".[167] James G. Randall emphasizes his tolerance and especially his moderation "in his preference for orderly progress, his distrust of dangerous agitation, and his reluctance toward ill digested schemes of reform". Randall concludes that, "he was conservative in his complete avoidance of that type of so-called 'radicalism' which involved abuse of the South, hatred for the slaveholder, thirst for vengeance, partisan plotting, and ungenerous demands that Southern institutions be transformed overnight by outsiders."[168]

By the late 1960s, liberals, such as historian Lerone Bennett, were having second thoughts, especially regarding Lincoln's views on racial issues.[169][170] Bennett won wide attention when he called Lincoln a white supremacist in 1968.[171] He noted that Lincoln used ethnic slurs, told jokes that ridiculed blacks, insisted he opposed social equality, and proposed sending freed slaves to another country. Defenders, such as authors Dirck and Cashin, retorted that he was not as bad as most politicians of his day;[172] and that he was a "moral visionary" who deftly advanced the abolitionist cause, as fast as politically possible.[173] The emphasis shifted away from Lincoln-the-emancipator to an argument that blacks had freed themselves from slavery, or at least were responsible for pressuring the government on emancipation.[174][175] Historian Barry Schwartz wrote in 2009 that Lincoln's image suffered "erosion, fading prestige, benign ridicule" in the late 20th century.[176] On the other hand, Donald opined in his 1996 biography that Lincoln was distinctly endowed with the personality trait of negative capability, defined by the poet John Keats and attributed to extraordinary leaders who were "content in the midst of uncertainties and doubts, and not compelled toward fact or reason".[177] In the 21st century, President Barack Obama named Lincoln his favorite president and insisted on using Lincoln's Bible for his swearing in of office at both his inaugurations.[178]

Notes

- ↑ Neeley (1993) p. 59; McPherson (1991) p. 65.

- ↑ Gienapp (2002) p. xi.

- ↑ Thomas (1952) pp. 403-404.

- ↑ Paludan pp. 34-35.

- ↑ McPherson (2008) p. 9; Thomas (1952) p. 229.

- ↑ Burlingame (2008) vol. 1 pp. 676–679; Holzer (2008) pp. 27–32.

- ↑ Thomas (1952) p. 226; Holzer (2008) p. 68.

- ↑ Thomas (1952) pp. 226-227; Holzer (2008) p. 75.