Portal (series)

| Portal | |

|---|---|

|

The official logo for the first Portal game. | |

| Genres | Puzzle, platform |

| Developers | Valve Corporation |

| Publishers | Valve Corporation |

| Platforms | Microsoft Windows, OS X, Linux, PlayStation 3, Xbox 360, Android |

| Year of inception | 2007 |

| First release |

Portal October 9, 2007 |

| Latest release |

The Lab April 5, 2016 |

Portal is a series of first-person puzzle-platform video games developed by Valve Corporation. Set in the Half-Life universe, the two games in the series, Portal (2007) and Portal 2 (2011), center on a woman, Chell, forced to undergo a series of tests within the Aperture Science Enrichment Center by a malicious artificial intelligence computer, GLaDOS, that controls the facility. Each test involves using the "Aperture Science Handheld Portal Device" - the "portal gun" - that creates a human-sized wormhole-like connection between nearly any two flat surfaces. The player-character or objects in the game world may move through portals, their momentum conserved. This allows complex "flinging" maneuvers to be used to cross wide gaps or perform other feats to reach the exit for each test chamber. A number of other mechanics, such as lasers, light bridges, tractor funnels, and turrets, exist to aid or hinder the player's goal to reach the exit.

The Portal games are noted for bringing students and their projects from the DigiPen Institute of Technology into Valve and extend their ideas into the full games. The portal concept was introduced by the game Narbacular Drop and led to the basis for the first game. Another game, Tag: The Power of Paint, formed the basis of surface-altering "gels" introduced in Portal 2.

Both games have received near-universal praise, and have sold millions of copies. The first game was released as part of a three-game compilation, The Orange Box, and though intended as a short bonus feature of the compilation, was instead considered the highlight of the three. Its success led to the creation of the much longer Portal 2, which included both single player and cooperative player modes; it too received mostly positive critical reviews. In addition to the challenging puzzle elements, both games are praised for its dark humor, written by Erik Wolpaw, Chet Faliszek, and Jay Pinkerton, voice work by actors Ellen McLain, Stephen Merchant, and J.K. Simmons, and musical songs by Jonathan Coulton. A number of spin-off media have been developed alongside the games, and several of the game elements have become parts of Internet memes.

Setting and characters

Both Portal games take place in the fictional "Aperture Science Enrichment Center". Aperture Science was founded by Cave Johnson (voiced by J.K. Simmons) and originally sought to make shower curtains for the military. Its research happened upon the discovery of portal technology, and soon became a direct competitor with Black Mesa Research Facility (from the Half-Life series) for government funding. Johnson acquired the rights to a disused salt mine in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, where they started building a labyrinth set of offices, laboratories, facilities, and test chambers. During this time, Johnson became poisoned from exposure to moon dust, a key component of the paint needed for the portal technology, and became increasingly deranged.

In Portal 2, the player explores these long-abandoned areas of Aperture, learning that the company had moved from testing on the country's finest, to paid volunteers, and ultimately to forcing its own employees to participate in testing. Near the point of his death, Johnson ordered his lifelong assistant Caroline (voiced by Ellen McLain) to be the first test subject for a mind-to-computer transfer; her personality would ultimately form the core of GLaDOS (also McLain). Sometime after Johnson's death, the old sections of the facility were vitrified, and a more modern facility built atop those ruins. GLaDOS was built to control the facility and monitor the tests, but researchers found that the computer had villainous tendencies, threatening to kill the entire staff before it was shut down in time. The Aperture researches constructed a number of "personality cores" that would fit onto GLaDOS to prevent her from turning against them. Despite this, on the day she was officially activated (coincidentally on "Take Your Daughter to Work Day"), she turned against the researchers and killed nearly everyone in the facility with lethal doses of neurotoxin gas. In the games and the comic Lab Rat, one employee Doug Rattmann survived due to his schizophrenia and distrust of GLaDOS. In trying to find a way to defeat GLaDOS, he finds that Chell, one of the human subjects kept in cryogenic storage within Aperture, has a high level of tenacity, and arranges for the events of Portal to occur by moving her to the top of GLaDOS' testing list. GLaDOS remain driven to test human subjects despite the lack of humans.

The player is introduced to Aperture in Portal, which is said by Valve to be set sometime between the events of Half-Life and Half-Life 2. The player-character Chell is awakened by GLaDOS for testing. Chell resists GLaDOS' lies and verbal ploys and succeeds to defeat GLaDOS' core, the destruction creating a portal implosion that sends Chell to the surface, unconscious. Rattmann, who has helped Chell by writing warning messages and directions to maintenance areas on the facility walls and had observed the final battle, escapes Aperture, but on witnessing a robot dragging Chell's body back inside, sacrifices his escape to assure that Chell is put into indefinite cryogenic storage. He himself is critically wounded but appears to make it to another cryogenic chamber, though his ultimate fate is not revealed.

Portal 2 takes place numerous years after the events of the first game; the Aperture facility has fallen into disrepair without GLaDOS. A personality core named Wheatley (Stephen Merchant) wakes Chell from her sleep to help her stop a reactor failure, but inadvertently awaken GLaDOS, who had redundantly backed up her personality. Though they defeat GLaDOS by putting Wheatley in her place, Wheatley is overwhelmed with power, sending Chell and GLaDOS, temporarily reduced to a small computer powered by a potato, to the old core of Aperture, where GLaDOS rediscovers her relation to Caroline. They return to the surface where they are forced to defeat Wheatley before his ineptitude with the Aperture systems causes the facility reactors to become critical and explode. GLaDOS is returned to her rightful place and returns the facility to normal. GLaDOS then lets Chell go, realizing that the prospect of trying to kill her is too much trouble. Instead, she turns to two robots of her own creation, Atlas and P-Body, to locate a mythical store of additional human subjects kept in cryogenic sleep for her to continue testing on.

In addition to these characters, the game includes numerous laser-seeking turrets that seek to kill the player-characters, though are apologetic for it; most are voiced by McLain, though some defective ones in the sequel are voiced by Nolan North. GLaDOS introduces Chell to the "Weighted Companion Cube", appearing similar to other Weighed Cubes (crates) in the game, but decorated with hearts on its sides; GLaDOS attempts to make Chell believe the Companion Cube is a sentient object and a key to her survival, before making Chell dispose of it in an incinerator prior to leaving a test chamber. Both games feature other personality cores that were constructed to keep GLaDOS in check; the first game includes three cores, the Morality, Curiosity, and Intelligence Cores, voiced by McLain as well as a snarling Anger Core voiced by Mike Patton. In Portal 2, three more such cores (beyond Wheatley) are introduced including the irrelevant Fact Core, the bold Adventure Core, and the space-obsessed Space Core, each voiced by North.

Gameplay

The player controls the main character (Chell in the single player campaigns, or one of Atlas and P-Body in the cooperative mode) from a first-person view, running, jumping, and interacting with switches or other devices. The player-characters are able to withstand large drops, but can be killed by falling in the toxic water of the facility, crushed to death, passing through laser grids, or fired on repeatedly by turrets.

Both games are generally divided into a series of test chambers; other sections of the game are more exploratory areas that connect these chambers. Each chamber has an exit door that must be reached, often requiring that certain conditions have been met such as having weighed down a large button with a "Weighted Cube", effectively a crate. These puzzles require the use of the Aperture Science Handheld Portal Device, the portal gun. The gun can shoot two portals, colored differently for identification, on any flat surface that is painted with a specific paint containing moon dust. Once both portal ends are placed, the player can walk the character between them, or carry objects with the portal gun through them. Portal ends can be re positioned as often as necessary, but certain actions, such as walking through "emancipation grills" or moving a surface with a portal will cause the portals to dissipate.

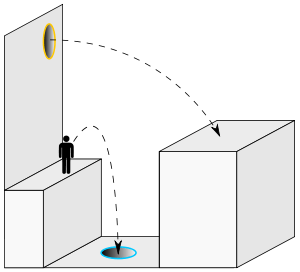

A critical feature of portals is that they retain the magnitude of momentum when an object travels through it; as stated by GLaDOS to the player in the first game, "Speedy thing goes in, speedy thing comes out". When portals are placed on non-parallel planes, this can create the effect of "flinging". Commonly, one uses gravity to build up their momentum when they fall into a portal, which flings them out of the other side to gain speed and distance that normal jumping and running could not generate. A leapfrogging effect can be used by placing portals in series during this flinging, gaining further momentum with each use.

Portals will also allow light and other objects to transfer through them, and numerous puzzles involve using portals to manipulate bouncing energy balls, lasers, "hard light" bridges, and tractor beams to access new locations or direct objects to specific receptacles that must be activated to open the level's exit. Portal 2 introduces "mobility gels" that can paint surfaces, including turrets and cubes, that can also move through portals though not directly by the player. The gels can create a surface that repels the player (Repulsion Gel), increases the player's speed (Propulsion Gel), or allows the surface to accept portals (Conversion Gel).

History

The concept of Portal was born out of a student project from the DigiPen Institute of Technology, entitled Narbacular Drop. The game included the aspects of placing portals on any flat surfaces and using them to maneuver around levels.[1][2] Valve's employees, attending a DigiPen career fair, saw their game and shortly later offered the entire team jobs at Valve to help expand on their idea.[3]

Valve originally saw Portal as an experimental game to be included with its upcoming compilation, The Orange Box, alongside its release of Half-Life 2: Episode Two and Team Fortress 2.[4] To give the game character, a minimal story, tied loosely with the Half-Life world, was written by Valve's Erik Wolpaw and Marc Laidlaw.[5] They needed a character to guide the player through the game, coming onto a polite but humorous artificial intelligence, which would ultimately become the character of GLaDOS.[5]

Portal's release with The Orange Box received near-universal praise, with the standalone game earning an aggregate Metacritic rating of 90 out of 100.[6] With success of the game, work on an expanded sequel began nearly immediately, expanding the development team from 8 to about 30-40 programmers.[7] Initial ideas for Portal 2 retained the idea of solving puzzles through scientific concepts, but eliminating the use of portals altogether; these versions did not fare well with test audiences nor with Gabe Newell, Valve's president; these ideas were dropped though saved for potential reuse in a different title by Valve.[8] Portal 2 development was restarted specifically to keep the portal concept but adding new elements to freshen the gameplay.[9][10]

During this period, Valve had witnessed another student project out of Digipen, Tag: The Power of Paint which allows the player to spray paint onto surfaces to alter their behavior, and brought them into Valve, though not initially as part of the Portal.[7] The Tag team had found a way to incorporate their paints with real-time fluid dynamics code previously made by Valve, and soon their concept for paints had become the "conversion gels" as part of Portal 2.[11][12][13][14]

To expand the title, Valve included a co-operative play mode, based on their own observations and stories from players about working out the solutions to Portal's puzzles in a group environment.[7][11][15] With this feature, they sought the ability to enable cross-platform play of Portal 2 between computers and consoles through Steamworks. This led to a surprise reveal by Newell that not only would Portal 2 be on the PlayStation 3 platform, after previously stating the difficulties in supporting this console, but that it would include support for cross-platform play between personal computers and PlayStation 3 players through a limited Steamworks interface.[10][16]

With the larger title, Valve brought in writer Jay Pinkerton formerly with National Lampoon, and Left 4 Dead writer Chet Faliszek to assist Wolpaw with the larger story. They built on the character of the Aperture Science facility, providing a deeper story for GLaDOS and Aperture's CEO Cave Johnson, as well as developing several concepts for "personality cores" ultimately to the creation of the Wheatley core character.[8][17]

Portal 2 was similarly released with high praise with a 95 out of 100 score on Metacritic.[18] Valve has continued to support the game through the release of two separate downloadable content packages, one introducing a new co-operative campaign,[19][20] and a second that incorporated an easy-to-learn level editor that allowed players to make their own test chambers and share these through the Steam Workshop to others.[21] Further on this, Valve has created a special version of the Portal level editor to be used alongside its "Steam in Schools" program as a means of using the game and editor to teach students about physics, math, and other lessons; Valve released this version of Portal 2 for free for educational use.[22]

Games

| 2007 | Portal |

| 2008 | Still Alive |

| 2009 | |

| 2010 | |

| 2011 | Portal 2 |

| 2012 | |

| 2013 | |

| 2014 | |

| 2015 | |

| 2016 | The Lab |

Portal

Portal was initially released in October 2007 as part of The Orange Box, a compilation of the Half-Life 2 and its two episodes, Team Fortress 2, and Portal. Valve had considered the inclusion of Portal as a bonus feature of the compilation; the game was purposely kept short such that if it did not meet expectations, players would have the rest of the content of The Orange Box as a "safety net".[23] Portal has since been repackaged on Microsoft Windows as a standalone game in April 2008.[24] A Mac OS X client was introduced simultaneously with the release of the Steam client for that platform in May 2010; as part of its promotion, the game was released free of charge for both platforms during which at least 1.5 million players downloaded the title.[25][26]

Portal: Still Alive

Portal: Still Alive was a standalone version of Portal with additional content for the Xbox Live Arcade, released in October 2008.[27] The game included new achievements, additional challenges from the existing test chambers, and additional non-story levels based on those found in the Flash-based Portal: The Flash Version created by We Create Stuff.[28]

Portal 2

Portal 2 was released as a standalone game in April 2011 on both computers and consoles.

The Lab

The Lab is a Portal-based title developed by Valve that is based on the use of virtual reality (VR), as part of its partnership with HTC and the VR headset, the HTC Vive. It was described as a "room-scale" VR experience, consisting of about a dozen small experimental experiences that highlight the use of VR; such include experiencing a fully panoramic view that has been stitched together from a number of photographs, an Angry Birds-like game where the player attempts to launch personality spheres into armies of turrets using a catapult, and a bow-and-arrow based game.[29] The title was announced at the 2016 Game Developers Conference, and was released as a free title on April 5, 2016, following the public release of the HTC Vive.[30]

Spin-off and related media

Portal 2: Lab Rat

To help develop the fictional history of Aperture Science, Valve created a digital comic to tell the story of the "Rat Man", a schizophrenic who is unseen in the games themselves but creates murals and scrawlings that guide Chell in both games.[31] The comic, "Portal 2: Lab Rat", takes place both during and after Portal, explaining the events that led to Portal 2.[32] The Rat Man's artwork appears early in Portal 2, where it retells the plot of Portal.[33] Michael Avon Oeming, who had worked on comics for Valve games Team Fortress 2 and Left 4 Dead,[34] and Valve in-house artist Andrea Wicklund drew the comic. Ted Kosmatka wrote most of the story with input from the Portal 2 writers.[35] The 27-page comic was made available online in two parts about two weeks before the game's release[36][37] and was also bundled with the game itself. Dark Horse Comics has published "Portal 2: Lab Rat" in a printed anthology of Valve comics, Valve Presents: The Sacrifice and Other Steam-Powered Stories, in November 2011.[38]

In the comic, Doug Rattmann (also known as The Rat Man) is a scientist working in the Aperture facility. He escapes GLaDOS's initial neurotoxin attack, but suffers symptoms as his schizophrenia medication runs out, causing hallucinations of his Weighted Companion Cube talking. Noticing that Chell is uniquely tenacious among the test subjects held by Aperture, Rattmann moves her to the top of the queue of testing subjects, thus starting the events of the first Portal. After Chell defeats GLaDOS, Rattmann escapes Aperture, but returns against the Companion Cube's objections when he sees the Party Escort Bot dragging an unconscious Chell back inside and into a disabled cryo chamber. He ensures that Chell is kept in indefinite suspended animation, but he is shot by a turret in the process. He then enters a stasis pod himself, leaving his fate afterward unknown.[39]

The Final Hours of Portal 2

The Final Hours of Portal 2 is a digital book written and created by Geoff Keighley. This digital book gives insight on the creation of Portal 2. Keighley had previously worked as an editor at GameSpot, writing several 10,000-word "Final Hours" pieces on various games where he visited the studios during the late development phases to document the creation of the game. One piece, "The Final Hours of Half-Life 2", allowed Keighley to interact with Valve during 2003 and 2004 and talk with the staff as they completed work on Half-Life 2.[40] Keighley wanted to recreate a similar work for Portal 2, with focus on making it an interactive work for the iPad.[41][42] Keighley was granted "fly on the wall" access to Valve when Portal 2 was being produced.[43] The initial iPad release was written by Keighley with work by Joe Zeff Design, a studio that had also produced digital applications for Time magazine.[41] The interactive work provides movie clips and short applications to demonstrate the various mechanics of the game and stages of the game's development. The work was later ported into a non-interactive eBook, and into an application with the same iPad interactivity on the Steam platform.[43] With the iPad and Steam version, Keighley is able to offer live updates to the work; upon release of the "Peer Review" downloadable content pack, the work was updated with an additional chapter discussing the creation of the new content and what new features players could expect in the future from Portal 2.[44]

Potato Sack

The Potato Sack was an alternate reality game conceived by Valve and 13 indie video game developers as a prelude to the release of Portal 2. Portal 2 had been announced by a similar game, where a patch applied to the Steam version of Portal in March 2010, provided clues heralding the official announcement. The Potato Sack game, launched on April 1, 2011, led to the reveal of "GLaDOS@home", a spoof of distributed computer challenges, to get players to cooperate on playing the independent games as to unlock Portal 2 on Steam about 10 hours before its planned release.

Portal: Uncooperative Cake Acquisition Game

A board game version of Portal is currently being developed by Cryptozoic Entertainment with oversight from Valve. Tentatively titled Portal: Uncooperative Cake Acquisition Game, the game was slated for release in October 2014. The Uncooperative Cake Acquisition Game is based on players manipulating their tokens - which are representative of unwitting test subjects - through various test chambers in the Aperture Laboratories. The goal being to test the most lucrative chambers while attempting to stall the progress of other players. Valve had approached Cryptozoic with the core concepts of the board game, which the publisher found only needed small modifications in gameplay for the purpose of balance.[45]

Merchandise

Valve has sold several Portal-based prints, T-shirts, and other memorabilia through its own store, often riding on the popularity of certain memes that the series has created.[46] When first released, both were sold out in under 24 hours.[5][47] Valve has also teams with other vendors for similar merchandise. WizKids will be releasing collectible miniatures of the turrets within the game.[48]

Film

On August 2011, Dan Trachtenberg released a fan film based on series called Portal: No Escape. The video would later become viral.[49][50]

During the 2013 D.I.C.E. Summit, Valve's Newell and film director J.J. Abrams announced plans to partner to create films on Valve's properties, including Half-Life and Portal.[51] In an interview in March 2016, Abrams stated that while he has been working on many other projects since, he still has plans to direct these films in the future, with both films in the writing stage.[52]

Portal in other video games

Poker Night 2

The main antagonist GLaDOS from Portal was included as the dealer in Poker Night 2. This game features portal themed unlockables such as playing cards, table and room. Wheatley is also featured as a bargaining chip.

Portal Pinball

A Portal based downloadable content for Zen Pinball 2 Pinball FX2 made in collaboration with Valve and Zen Studios.[53]

Lego Dimensions

The cross-franchise game Lego Dimensions, which incorporates the use of Lego minifigures with a special gamepad, includes Portal-themed elements, as demonstrated during its Electronic Entertainment Expo 2015 trailer. A Portal-themed level appears as part of the main story campaign, with GLaDOS playing a significant role in the game's plot. A Chell minifigure was released that comes packaged with buildable sentry turret and companion cube; the figure unlocks an additional level and open-world area based on the series when used in-game.[54][55] The Portal levels include Easter eggs based on Doug Rattman hiding himself away.[56] The game also features a new song written by Jonathan Coulton and performed by Ellen McLain that plays over the end credits (done in the style of Portal 2's credits).

Defense Grid: The Awakening's "You Monster" DLC

GLaDOS guest stars in Defense Grid: The Awakening in a full-story expansion.[57]

Bit.Trip Presents... Runner2: Future Legend of Rhythm Alien

Atlas appears as a player-character in the downloadable content package for Bit.Trip Presents... Runner2: Future Legend of Rhythm Alien.[58]

The Stanley Parable

The cell from the opening of Portal makes an appearance as part of one of many endings in this game that satirizes video games in general.

The Ball

Early in the game you come across a companion cube while solving one of the puzzles. After solving this puzzle, part of the wall crumbles. This reveals a simple Portal test chamber. You must use the companion cube to pass the test and advance in the game.

Portal in education

The Portal games have found application in educational aspects outside of game development. The first game was praised as an example of instructional scaffolding where the student is first given an environment to learn new tools with sufficient hand-holding, but these facets are slowly removed as the student proceeds.[59] At least one college, Wabash College, introduced Portal as part of required coursework; at Wabash, the game is used as an example of Erving Goffman's dissemination on dramaturgy, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life.[60][61][62]

At a mid-2011 presentation at the 2011 Games for Change Festival at New York University, Gabe Newell stated Valve's intention to direct Portal and Portal 2 towards education. Newell stated that Valve "doesn’t see divide between making a game that can do well and be educational", and was already working with schools to develop lesson plans around the game.[63] In one example, Valve brought in students from nearby Evergreen School to watch them interact with the game in an educational setting.[64] As part of this effect, the company promoted Portal for free use by any user during September 2011.[65]

In speaking at the 2012 Games for Change Festival, Newell said that the response to these efforts was praised by educators.[66] Their efforts culminated in a "Teach with Portals" program that Newell announced at the Festival. The effort is built on a standalone "Puzzle Maker" that incorporates the level editor for Portal 2 that was released as free content for the game in early 2012. Valve had built the Puzzle Maker with the aid of educators, as to make it suitable for lesson plans as well as making it as easy for teachers to use to construct such plans. The Puzzle Maker is not limited to physics, but designed to be modular so that other fields, such as fundamental electronics or chemistry, could be included.[66] The "Teach with Portals" initiative is built atop of a stripped-down version of the Steam client, "Steam for Schools", that is designed to be used in schools, allowing instructors to control the installation of the games and lesson plans on the students' computers. These tools, as well as copies of Portal 2 and the Puzzle Maker, are being offered for free for all educators.[66]

Portal in popular culture

Several elements of the Portal series have entered the popular culture, typically as bases for Internet memes.

- During Portal, the player explores areas outside of the test chambers where scrawled messages left by Rattmann and others warn of GLaDOS' deception. In particular, while GLaDOS promises that Chell will receive cake for completing the training courses, the messages alert that this reward does not exist, and that "the cake is a lie". The phrase "the cake is a lie" became an Internet meme, leading to numerous cake-related jokes, as well as its adaption as a term relating to a false promise. When writing Portal 2, Wolpaw stated that they were so sick of cake jokes that they purposely avoided any reference to that, save for one subtle nod.

- In one Portal level, the player is given an inanimate weighted cube with hearts on its side, called the "Weighted Companion Cube" by GLaDOS. GLaDOS proceeds to taunt the player by asserting that the Cube is alive, that it is Chell's friend, and otherwise attempting to form an attraction to it. The player is required to use the Weighted Companion Cube to complete the level, but to exit the level, the player must then drop the Cube into an incinerator. The Weighted Companion Cube became a popular items to include on Portal-themed merchandise.

- Portal's credit sequence plays over the song "Still Alive", composed by Jonathan Coulton, and, in its original form, song by Ellen McLain in the GLaDOS voice. The song, sung from GLaDOS's point of view as considering her defeat as "a success", contributed to the positive response of the game as well as highlight Coulton's work to players, and leading to Valve bringing back Coulton to record a credits song for Portal 2.[67]

- Portal is referenced by Glenn in The Walking Dead episode "Pretty Much Dead Already".

- In an episode of The Amazing World of Gumball entitled "The Points", Tobias pretends to acquire a Portal gun. He puts a portal in the sky and another below it, causing Gumball to fall through continuously, a joke many players do in the game.

In considering the popularity of the cake meme from Portal, Wolpaw and the team set up to write Portal 2 without intentionally aiming to include any meme-worthy material in the game. Despite this, several elements have been reused in humor across the Internet.

- When the player completes the final test chamber in the underground Aperture facility, a pre-recorded message from CEO Cave Johnson plays. In it, Cave Johnson, having been lethally poisoned with moon dust, gives a speech about the popular saying "When life gives you lemons, make lemonade". Here, he trash talks the analogy, saying the proper response to "life giving lemons" is to invent combustible lemons, and use them to burn life's house down.

- One of the personality cores introduced in the end game is obsessed with getting into outer space, and does end up there after the finale, shouting annoyingly, "I'm in space!" among other lines. This "Space Core" has become its own meme, and furthering it, Valve prepared a special bit of downloadable content for the game The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim, where the player can find and collect the Space Core in their inventory. The Space Core's name itself is a pun on the term 'space corps', and might also be interpreted as 'astronaut corps'.

References

- ↑ "Things are heating up!". Narbacular Drop official site. 2006-07-17. Archived from the original on 2007-09-28. Retrieved 2006-07-21.

- ↑ Berghammer, Billy (2006-08-25). "GC 06:Valve's Doug Lombardi Talks Half-Life 2 Happenings". Game Informer. Archived from the original on 2007-10-02. Retrieved 2007-09-27.

- ↑ Dudley, Breir (2011-04-17). "'Portal' backstory a real Cinderella tale". Seattle Times. Retrieved 2011-04-17.

- ↑ Elliot, Shawn (2008-02-06). "Beyond the Box: Orange Box Afterthoughts". 1UP. Retrieved 2008-02-14.

- 1 2 3 Reeves, Ben (2010-03-10). "Exploring Portal's Creation And Its Ties To Half-Life 2". Game Informer. Retrieved 2010-03-10.

- ↑ "Portal (pc: 2007): Reviews". Metacritic. Retrieved 2007-10-22.

- 1 2 3 Remo, Chris (2010-09-20). "Synthesizing Portal 2". Gamasutra. Retrieved 2010-09-20.

- 1 2 Alexander, Leigh (2011-05-06). "Valve's Wolpaw Offers Behind-The-Scenes Peek Into Portal 2". Gamasutra. Retrieved 2011-05-06.

- ↑ Tolito, Stephen (2011-04-21). "Portal 2 Wasn't Going to Include Portals, According To New iPad App". Kotaku. Retrieved 2011-05-06.

- 1 2 Keighley, Geoff (2011). The Final Hours of Portal 2. ASIN B004XMZZKQ. Also available as iPad or Steam application.

- 1 2 Kao, Ryan (2010-09-04). "Portal 2: A Look at the Hotly Anticipated Videogame". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2010-09-04.

- ↑ Leahy, Brian (2010-03-08). "Valve Hires DigiPen Team; Seemingly for Portal 2". Shacknews. Retrieved 2010-03-08.

- ↑ Ryckert, Dan (2010-03-08). "From Narbacular Drop To Portal". Game Informer. Retrieved 2010-03-08.

- ↑ Gaskill, Jake (2010-06-18). "E3 2010: Portal 2 Preview". G4TV. Retrieved 2010-06-19.

- ↑ Stewart, Keith (2010-06-18). "E3 2010: Portal 2 preview". The Guardian. Retrieved 2010-06-21.

- ↑ Peckham, Matt (2010-06-15). "Valve Apologizes For Sony-Bashing, Announces Portal 2 for PS3". PC World. Retrieved 2010-06-15.

- ↑ Welch, Oli (2011-04-25). "Portal 2: "Let's make Caddyshack"". Eurogamer. Retrieved 2011-04-25.

- ↑ "Portal 2 for PC Reviews, Ratings, Credits, and More". Metacritic. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- ↑ Ohannessian, Kevin (2011-04-27). "Portal 2's Creators On Crafting Games Through Experiential Stories". Fast Company. Retrieved 2011-04-27.

- ↑ Dutton, Fred (2011-09-30). "Portal 2 DLC release date". Eurogamer. Retrieved 2011-09-30.

- ↑ Helgeson, Matt (2012-05-10). "Portal 2's Perpetual Testing Initiative Off To A Good Start". Game Informer. Retrieved 2012-05-11.

- ↑ Alexander, Leigh (2012-06-20). "Valve helps educators Teach With Portals". Gamasutra. Retrieved 2012-06-20.

- ↑ VanBurkleo, Meagan (April 2010). "Portal 2". Game Informer. pp. 50–62.

- ↑ Kiestmann, Ludwig (2008-03-06). "Individual Orange Box games hit retail April 9". Joystiq. Retrieved 2008-03-06.

- ↑ Caolli, Eric (2010-05-12). "Steam Launched For Mac, Portal Offered For Free". Gamasutra. Retrieved 2010-05-13.

- ↑ Remo, Chris (2010-05-19). "Portal Racks Up 1.5M Free Downloads On PC, Mac". Gamasutra. Retrieved 2010-05-19.

- ↑ Faylor, Chris (2008-10-16). "Portal: Still Alive Hits Xbox Live Arcade Next Wed; Promises Cake and Companionship". Shacknews. Retrieved 2008-10-16.

- ↑ Remo, Chris (2008-07-20). "Portal: Still Alive Explained". GameSetWatch. Retrieved 2008-07-21.

- ↑ Hollister, Sean (2016-03-16). "Valve's 'Lab' and desktop theater mode could be the perfect introduction to virtual reality (hands-on)". CNet. Retrieved 2016-03-17.

- ↑ Perez, Daniel (2016-03-07). "Valve's 'The Lab' is a compilation VR experience set in Portal's universe releasing this Spring". Shacknews. Retrieved 2016-03-07.

- ↑ Mawson, Jarrod (2001-04-07). "Portal 2 'Rat Man' comic revealed". PALGN. Retrieved 2011-08-06.

- ↑ Brown, David (2011-03-04). "Portal 2 developer interview: Chet Falisek and Erik Wolpaw". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 2011-03-04.

- ↑ Griliopoulos, Dan (2011-03-28). "Portal 2: Test Subjects". IGN. Retrieved 2011-03-28.

- ↑ Goldman, Tom (2011-04-07). "Official Portal 2 Comic Reveals the Truth About Cake". The Escapist. Retrieved 2011-08-06.

- ↑ Esposito, Joey (2011-04-06). "Expanding the World of Portal 2". IGN. Retrieved 2011-04-06.

- ↑ Esposito, Joey (2011-04-08). "Portal 2: Lab Rat – Part 1". IGN. Retrieved 2011-04-11.

- ↑ Esposito, Joey (2011-04-11). "Read Portal 2: Lab Rat – Part 2". IGN. Retrieved 2011-04-11.

- ↑ Rose, Mike (2011-07-11). "Comic Book Based On Valve Strips Coming This November". Gamasutra. Retrieved 2011-07-11.

- ↑ "Portal 2: Lab Rat". Retrieved 2001-08-06.

- ↑ Takahashi, Dean (2011-04-21). "Game journalist may cash in on the making of Portal 2". Venture Beat. Retrieved 2012-01-26.

- 1 2 Snider, Mike (2011-04-25). "GameTrailers TV's Geoff Keighley gets interactive with new 'Portal 2' iPad app". USA Today. Retrieved 2012-01-26.

- ↑ Keighley, Geoff (2004). "The Final Hours of Half-Life 2". GameSpot. Retrieved 2012-01-26.

- 1 2 Hill, Owen (2011-05-18). "Portal 2 – The Final Hours now on Steam". PC Gamer. Retrieved 2012-01-26.

- ↑ Tolito, Stephan (2011-10-18). "Valve Tinkering With an Excellent Portal 2 Feature That Talks Back". Kotaku. Retrieved 2011-10-19.

- ↑ Sarkar, Samit (2014-03-05). "How Valve and Cryptozoic came together for a Portal board game". Polygon. Retrieved 2014-03-05.

- ↑ "Steam Updates: Friday, November 9, 2007". Valve. 2007-11-09. Retrieved 2007-11-09.

- ↑ De Marco, Flynn (2007-12-15). "Official Plush Weighted Companion Cube Sells Out". Kotaku. Retrieved 2008-02-21.

- ↑ "NECA/WizKids Announce New Portal 2 Sentry Turret Collectible Figures" (Press release). WizKids. 2012-07-05. Retrieved 2012-07-09.

- ↑ Wood, Roy (August 27, 2011). "Portal: No Escape, A Live Action Short Film". Retrieved September 19, 2016.

- ↑ Skipper, Ben (January 15, 2016). "Cloverfield sequel director Dan Trachtenberg caught Hollywood's eye with this Portal fan film". Retrieved September 19, 2016.

- ↑ Goldbarb, Andrew (2013-02-06). "DICE: JJ ABRAMS, GABE NEWELL PARTNERING FOR GAME, MOVIES". IGN. Retrieved 2016-03-13.

- ↑ Strom, Steven (2016-03-12). "J.J. ABRAMS: PORTAL, HALF-LIFE MOVIES STILL HAPPENING". IGN. Retrieved 2016-03-12.

- ↑ "Portal is turning into a pinball game". 2015-05-05.

- ↑ Phillips, Tom. "Lego Dimensions' Portal 2 and Doctor Who expansions confirmed • Eurogamer.net". Eurogamer. Gamer Network. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

- ↑ Ogilvie, Trisian (2015-06-17). "E3 2015: LEGO DIMENSIONS BUILDS A PORTAL GAME FOR EVERYONE". IGN. Retrieved 2015-06-29.

- ↑ Philips, Tom (2016-11-18). "It took Lego Dimensions players over a year to find the secret Portal Easter egg". Eurogamer. Retrieved 2016-11-18.

- ↑ "Defense Grid: You Monster". 2015-02-02.

- ↑ Vandell, Perry (July 10, 2013). "Psychonauts, Spelunky, and Portal 2 characters join the cast of Runner 2". PC Gamer. Retrieved August 26, 2015.

- ↑ Schiller, Nicholas (2008). "A Portal to Student Learning: What Instruction Librarians can Learn from Video Game Design". Reference Services Review. 36 (4): 351–365. doi:10.1108/00907320810920333. Retrieved 2009-06-25.

- ↑ Johnson, Daniel (2009-06-01). "Column: 'Lingua Franca' – Portal and the Deconstruction of the Institution". GameSetWatch. Retrieved 2009-06-01.

- ↑ Goldman, Tom (2010-08-22). "College Professor Requires Students to Study Portal". The Escapist. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ↑ Klepek, Patrick (2011-05-18). "Intro to GLaDOS 101: A Professor's Decision to Teach Portal". Giant Bomb. Retrieved 2011-05-18.

- ↑ Wilde, Tyler (2011-06-23). "Newell: Portal 2 has hit three million sales". PC Gamer. Retrieved 2012-06-28.

- ↑ Kuchera, Ben (2011-09-16). "Portal is used to teach science as Valve gives game away for limited time". Ars Technica. Retrieved 2012-06-28.

- ↑ Crossley, Rob (2011-09-16). "Portal goes free in Valve education push". Develop. Retrieved 2012-06-28.

- 1 2 3 Coffin, Ariane (2012-06-28). "Valve Wants Schools to Teach With Portals". Wired. Retrieved 2012-06-28.

- ↑ Hilliard, Kyle (2013-06-07). "The Best Video Game Surprise Songs". Game Informer. Retrieved 2013-06-07.