Poaching

| Part of a series on Law and the Environment |

|

| Environmental Law |

| Pollution control law |

|---|

| Natural resources law |

| Reference materials |

| Related topics |

Poaching has traditionally been defined as the illegal capturing of wild animals, usually associated with land use rights.[1]

According to Encyclopædia Britannica, poaching was performed by impoverished peasants for subsistence purposes and a supplement for meager diets.[2] Poaching was as well set against the hunting privileges of nobility and territorial rulers.[3] By contrast, stealing domestic animals (as in cattle raiding, for example) classifies as theft, not as poaching.[4]

Since the 1980s, the term "poaching" has also referred to the illegal harvesting of wild plant species.[5][6][7] In agricultural terms, the term 'poaching' is also applied to the loss of soils or grass sward by the damaging action of feet of livestock which can affect availability of productive land, water pollution through increased runoff and welfare issues for cattle.[8][9][10]

Legal aspects

Continental Europe

Austria and Germany refer to poaching not as theft, but as intrusion in third party hunting rights.[11] While Germanic law allowed any free man including peasants to hunt, especially on the commons, roman law restricted hunting for the rulers. Medieval Europe saw feudal territory rulers from the king downward trying to enforce exclusive rights of the nobility to hunt and fish on the lands they ruled. Poaching was being deemed a serious crime punishable by imprisonment but the enforcement, till the 16th century, was comparably weak.[12] Peasants still were able to continue small game hunting, the right of the nobility to hunt was restricted in the 16th century and transferred to land ownership.[12]

The development of modern hunting rights is closely connected to the comparably modern idea of exclusive private property of land. In the 17th and 18th centuries the restrictions on hunting and shooting rights on private property were being enforced by gamekeepers and foresters. They denied shared usages of forests, e.g. resin collection and wood pasture and the peasant's right to hunt and fish.[13] However, comparably easy access to rifles increasingly allowed peasants and servants to poach end of the 18th century.

The low quality of guns made it necessary to approach to the game as close as 30 meters (33 yards). For example, poachers in the Salzburg region then were around 30 years old men, not yet married and usually alone on their illegal trade.[12] Hunting was being used in the 18th century as a theatrical demonstration of aristocratic rule of the land and had a strong impact on land use patterns as well.[14] Poaching in so far inferred not only with property rights but clashed symbolically with the power of the nobility. The years between 1830 and 1848 saw a strong increase in poaching and poaching related deaths in Bavaria.[15] The revolution of 1848 was interpreted as a general allowance for poaching in Bavaria. The reform of hunting law in 1849 reduced legal hunting to rich land owners and the bourgeoisie able to pay the hunting fees and led to disappointment and ongoing praise of poachers among the people .[15] Some of the frontier region, where smuggling was of importance, showed especially strong resistance. In 1849, the Bavarian military forces were being asked to occupy a number of municipalities on the frontier to Austria. Both, in Wallgau (today a part of Garmisch-Partenkirchen) and in Lackenhäuser, (close to Wegscheid in the Bavarian forest) one soldier per household was to be fed and kept for a month as part of a military mission to quell the uproar. The people of Lackenhäuser had had several skirmishes about poached deer with Austrian foresters and even military and were known as well armed pertly poachers (kecke Wilderer).[3]

United Kingdom

Poaching, like smuggling, has a long counter-cultural history. The verb poach is derived from the Middle English word pocchen literally meaning bagged, enclosed in a bag.[16][17]

Poaching was dispassionately reported for England in "Pleas of the Forest", transgressions of the rigid Anglo-Norman Forest Law.[18] William the Conqueror, a great lover of hunting, had established and enforced a system of forest law. This operated outside the common law, and served to protect game animals and their forest habitat from destruction. 1087, a poem, "The Rime of King William" in the Peterborough Chronicle, expressed English indignation. Poaching was romanticized in literature from the time of the ballads of Robin Hood, as an aspect of the "greenwood" of Merry England. Non est inquirendum, unde venit venison ("It is not to be inquired, whence comes the venison"), observed Guillaume Budé in his Traitte de la vénerie.[19] However, the English nobility and land owners were much more successful in enforcing the modern concept of property, expressed e.g. in the enclosures and later in the highland Clearances, both forced displacement of people from traditional land tenancies. The 19th century saw the rise of acts of legislation, such as the Night Poaching Act 1828 and Game Act 1831 in the United Kingdom, and various laws elsewhere.

Poaching in the USA

In North America, the blatant defiance of the laws by poachers escalated to armed conflicts with law authorities, including the Oyster Wars of the Chesapeake Bay, and the joint US-British Bering Sea Anti-Poaching Operations of 1891 over the hunting of seals.

Violations of hunting laws and regulations concerning wildlife management, local or international wildlife conservation schemes constitute wildlife crimes that are typically punishable.[20][21] The following violations and offenses are considered acts of poaching in the USA:

- Hunting, killing or collecting wildlife that is listed as endangered by IUCN and protected by law such as the Endangered Species Act, the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 and international treaties such as CITES.[20]

- Fishing and hunting without a license.[21][22]

- Capturing wildlife outside legal hours and outside the hunting season;[20][21] usually the breeding season is declared as the closed season during which wildlife is protected by law.

- Prohibited use of machine guns, poison, explosives, snare traps, nets and pitfall traps.[20]

- Prohibited use of baiting with food, decoys or recorded calls in order to increase chances for shooting wildlife.[20]

- Hunting from a moving vehicle or aircraft.[20]

- Shining deer with a spotlight at night to impair its natural defenses and thus facilitate an easy kill is considered animal abuse.[23] This hunting method is illegal in California, Virginia, Connecticut, Florida, Michigan and Tennessee.[20]

- Taking wildlife on land that is restricted, owned by or licensed to somebody else.

- The animal or plant has been tagged by a researcher.

Environmental law

In 1998 environmental scientists from the University of Massachusetts Amherst proposed the concept of poaching as an environmental crime, defining any activity as illegal that contravenes the laws and regulations established to protect renewable natural resources including the illegal harvest of wildlife with the intention of possessing, transporting, consuming or selling it and using its body parts. They considered poaching as one of the most serious threats to the survival of plant and animal populations.[6] Wildlife biologists and conservationists consider poaching to have a detrimental effect on biodiversity both within and outside protected areas as wildlife populations decline, species are depleted locally, and the functionality of ecosystems is disturbed.[24]

Stephen Corry, director of the human-rights group Survival International, has argued that the term "poaching" has at times been used to criminalize the traditional subsistence techniques of indigenous peoples and bar them from hunting on their ancestral lands, when these lands are declared wildlife-only zones.[25] Corry argues that parks such as the Central Kalahari Game Reserve are managed for the benefit of foreign tourists and safari groups, at the expense of the livelihoods of tribal peoples such as the Kalahari Bushmen.[26]

Motives

Sociological and criminological research on poaching indicates that in North America people poach for commercial gain, home consumption, trophies, pleasure and thrill in killing wildlife, or because they disagree with certain hunting regulations, claim a traditional right to hunt, or have negative dispositions toward legal authority.[6] In rural areas of the United States, the key motives for poaching are poverty.[27] Interviews conducted with 41 poachers in the Atchafalaya River basin in Louisiana revealed that 37 of them hunt to provide food for themselves and their families; 11 stated that poaching is part of their personal or cultural history; nine earn money from the sale of poached game to support their families; eight feel exhilarated and thrilled by outsmarting game wardens.[28]

In African rural areas, the key motives for poaching are the lack of employment opportunities and a limited potential for agriculture and livestock production. Poor people rely on natural resources for their survival and generate cash income through the sale of bushmeat, which attracts high prices in urban centres. Body parts of wildlife are also in demand for traditional medicine and ceremonies.[24] The existence of an international market for poached wildlife implies that well-organised gangs of professional poachers enter vulnerable areas to hunt, and crime syndicates organise the trafficking of wildlife body parts through a complex interlinking network to markets outside the respective countries of origin.[29][30]

In a study conducted in Tanzania by two scientists named Paul Wilfred and Andrew Maccoll explored why the people in Tanzania poached certain species and when they are more likely to do so. They decided to interview people from multiple villages who lived near the Ugalla Game Reserve. To make sure the interview and their results were unbiased, they randomly picked several villages and several families from each village to interview.[31]

One of the major cases of poaching is for bushmeat, or meat consumed from non-domesticated species of animals from all sorts of classes such as mammals or birds. Usually, bushmeat is considered a subset of poaching due to the hunting of animals regardless of the laws that conserve certain species of animals. Poachers hunt for bushmeat for both consumption and for profit.[31]

The conclusion of the study found that many families would consume more bushmeat if there weren’t protein alternatives such as fish and the further away the families were from the reserve, the less likely they were to illegally hunt the wildlife for bushmeat. Finally, families were more likely to hunt for bushmeat right before harvest season and during heavy rains as before the harvest season, there is not much agricultural work and heavy rainfall obscures human tracks, making it easier for poachers to get away with their crimes.[31]

Poverty seems to be a large impetus to cause people to poach, something that affects both residents in Africa and Asia. For example, in Thailand, there are anecdotal accounts of the desire for a better life for children, which drive rural poachers to take the risk of poaching even though they dislike exploiting the wildlife.[32]

Another major cause of poaching is due to the cultural high demand of wildlife products, such as ivory, that are seen as symbols of status and wealth in China. According to Joseph Vandegrift, China saw an unusual spike in demand for ivory in the twenty-first due to the economic boom that allowed more middle-class Chinese to have a higher purchasing power that incentivized them to show off their newfound wealth using ivory, a rare commodity since the Han Dynasty.[33]

In China, there are problems with wildlife conservation, specifically relating to tigers. Several authors collaborated on a piece titled “Public attitude toward tiger farming and tiger conservation in Beijing, China”, exploring the option of whether it would be a better policy to raise tigers on a farm or put them in a wildlife conservation habitat to preserve the species. Conducting a survey on 1,058 residents of Beijing, China with 381 being university students and the other 677 being regular citizens, they tried to gauge public opinion about tigers and conservation efforts for them. They were asked questions regarding the value of tigers in relations to ecology, science, education, aestheticism, and culture. However, one reason emerged as to why tigers are still highly demanded in illegal trading: culturally, they are still status symbols of wealth for the upper class, and they are still thought to have mysterious medicinal and healthcare effects.[34]

Effects of poaching

The detrimental effects of poaching can include:

- Defaunation of forests: predators, herbivores and fruit-eating vertebrates cannot recover as fast as they are removed from a forest; as their populations decline, the pattern of seed predation and dispersal is altered; tree species with large seeds progressively dominate a forest, while small-seeded plant species become locally extinct.[35]

- Reduction of animal populations in the wild and possible extinction.

- The effective size of protected areas is reduced as poachers use the edges of these areas as open-access resources.[36]

- Wildlife tourism destinations face a negative publicity; those holding a permit for wildlife-based land uses, tourism-based tour and lodging operators lose income; employment opportunities are reduced.[24]

- Emergence of zoonotic diseases caused by transmission of highly variable retrovirus chains:

- Outbreaks of the Ebola virus in the Congo Basin and in Gabon in the 1990s have been associated with the butchering of apes and consumption of their meat.[37]

- The outbreak of SARS in Hong Kong is attributed to contact with and consumption of meat from masked palm civets, raccoon dogs, Chinese ferret-badgers and other small carnivores that are available in southern Chinese wildlife markets.[38]

- Bushmeat hunters in Central Africa infected with the human T-lymphotropic virus were closely exposed to wild primates.[39]

- Results of research on wild chimpanzees in Cameroon indicate that they are naturally infected with the simian foamy virus and constitute a reservoir of HIV-1, a precursor of the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome in humans.[40]

Many tribal people in Africa, Brazil and India rely on hunting for food and have become victims of the fallout from poaching.[41] In the Indian Kanha Tiger Reserve, they are prevented from hunting, and were illegally evicted from their lands following the creation of nature reserves aimed to protect animals.[42] Tribal people are often falsely accused of contributing to the decline of wildlife. In India for example, they bear the brunt of anti-tiger poaching measures,[43] despite the main reason for the tiger population crash in the 20th century being due to hunting by European colonists and Indian royalties.[44] Stephen Corry, director of the human-rights group Survival International, argues that indigenous peoples have shaped landscapes and managed animal populations for millennia. He asserts that conservation organizations such as the World Wildlife Fund apply the term "poaching" unfairly to tribal people engaging in subsistence hunting while supporting trophy hunting by tourists for a fee.[45]

Products

The body parts of many animals, such as tigers and rhinoceroses, are believed to have certain positive effects on the human body, including increasing virility and curing cancer. These parts are sold in areas where these beliefs are practiced – mostly Asian countries particularly Vietnam and China – on the black market.[46]

Traditional Chinese medicine often incorporates ingredients from all parts of plants, the leaf, stem, flower, root, and also ingredients from animals and minerals. The use of parts of endangered species (such as seahorses, rhinoceros horns, binturong and tiger bones and claws) has created controversy and resulted in a black market of poachers.[47][48] Deep-seated cultural beliefs in the potency of tiger parts are so prevalent across China and other east Asian countries that laws protecting even critically endangered species such as the Sumatran tiger fail to stop the display and sale of these items in open markets, according to a 2008 report from TRAFFIC.[49] Popular "medicinal" tiger parts from poached animals include tiger genitals, culturally believed to improve virility, and tiger eyes.

Rhino populations face extinction because of demand in Asia (for traditional medicine and as a luxury item) and in the Middle East (where horns are used for decoration).[50] A sharp surge in demand for rhino horn in Vietnam was attributed to rumors that the horn cured cancer, even though the rumor has no basis in science.[51][52] Recent prices for a kilo of crushed rhino horn have gone for as much as $60,000, more expensive than a kilo of gold.[53] Vietnam is the only nation which mass-produces bowls made for grinding rhino horn.[54]

Ivory, which is a natural material of several animals, plays a large part in the trade of illegal animal materials and poaching. Ivory is a material used in creating art objects and jewelry where the ivory is carved with designs. China is a consumer of the ivory trade and accounts for a significant amount of ivory sales. In 2012, The New York Times reported on a large upsurge in ivory poaching, with about 70% of all illegal ivory flowing to China.[55][56]

Fur is also a natural material which is sought after by poachers. A Gamsbart, literally chamois beard, a tuft of hair traditionally worn as a decoration on trachten-hats in the alpine regions of Austria and Bavaria formerly was worn as a hunting (and poaching) trophy. In the past, it was made exclusively from hair from the chamois' lower neck.[57]

Africa

Members of the Rhino Rescue Project have implemented a technique to combat rhino poaching in South Africa by injecting a mixture of indelible dye and a parasiticide, which enables tracking of the horns and deters consumption of the horn by purchasers. Since rhino horn is made of keratin, advocates say the procedure is painless for the animal.[58]

Another initiative that seeks to protect Africa's elephant populations from poaching activities is the Tanzanian organization Africa's Wildlife Trust. Hunting for ivory was banned in 1989, but poaching of elephants continues in many parts of Africa stricken by economic decline.

The International Anti-Poaching Foundation has a structured military-like approach to conservation, employing tactics and technology generally reserved for the battlefield. Founder Damien Mander is an advocate of the use of military equipment and tactics, including Unmanned Aerial Vehicles, for military-style anti-poaching operations.[59][60][61] Such military-style approaches have garnered some criticism. Rosaleen Duffy of the University of London writes that military approaches to conservation fail to resolve the underlying reasons leading to poaching, and do not tackle either "the role of global trading networks" or continued demand for illegal animal products. According to Duffy, such methods "result in coercive, unjust and counterproductive approaches to wildlife conservation".[62]

Chengeta Wildlife is an organization that works to equip and train wildlife protection teams and lobbies African governments to adopt anti-poaching campaigns. [63]

Jim Nyamu's elephant walks are part of attempts in Kenya to reduce ivory poaching.[64]

Asia

Large quantities of ivory are sometimes destroyed as a statement against poaching (aka "ivory crush").[65] In 2013 the Philippines were the first country to destroy their national seized ivory stock.[66] In 2014 China followed suit and crushed six tons of ivory as a symbolic statement against poaching.[67][68]

There are two main solutions according to Frederick Chen that would attack the supply side of this poaching problem to reduce its effects: enforcing and enacting more policies and laws for conservation and by encouraging local communities to protect the wildlife around them by giving them more land rights.[34]

Nonetheless, Frederick Chen wrote about two types of effects stemming from demand-side economics: the bandwagon and snob effect. The former deals with people desiring a product due to many other people buying them while the latter is similar with one distinct difference: people will clamor to buy something if it denotes wealth that only a few elites could possibly afford. Therefore, the snob effect would offset some of the gains made by anti-poaching laws, regulations, or practices—if you cut off parts of the supply, the rarity and price of the object would increase and only a select few would have the desire and purchasing power for it. While approaches to dilute mitigate poaching from a supply-side may not be the best option as people can become more willing to purchase rarer items, especially in countries gaining more wealth and therefore higher demand for illicit goods—Frederick Chen still advocates that we should also focus on exploring ways to reduce the demand for these goods to better stop the problem of poaching.[69]

Another solution to alleviate poaching proposed in Tigers of the World was about how to implement a multi-lateral strategy that targets different parties to conserve wild tiger populations in general. This multi-lateral approach include working with different agencies to fight and prevent poaching since organized crime syndicates benefit from tiger poaching and trafficking; therefore, there is a need to raise social awareness and implement more protection and investigative techniques. For example, conservation groups raised more awareness amongst park rangers and the local communities to understand the impact of tiger poaching—they achieved this through targeted advertising that would impact the main audience. Targeting advertising using more violent imagery to show the disparity between tigers in nature and as a commodity made a great impact on the general population to combat poaching and indifference towards this problem. The use of spokespeople such as Jackie Chan and other famous Asian actors and models who advocated against poaching also helped the conservation movement for tigers too.[32]

Poaching has many causes in both Africa and China. The issue of poaching is not a simple one to solve as traditional methods to counter poaching have not taken into the account the poverty levels that drive some poachers and the lucrative profits made by organized crime syndicates who deal in illegal wildlife trafficking. Conservationists hope the new emerging multi-lateral approach, which would include the public, conservation groups, and the police, will be successful for the future of these animals.

United States of America

Some game wardens have made use of robotic decoy animals placed in high visibility areas to draw out poachers for arrest after the decoys are shot[70] and decoys with robotics to mimic natural movements are also in use by law enforcement.[71]

Sturgeon and paddlefish (aka "spoonbill catfish") are listed as species of "special concern" by the U.S. Federal government, but are only banned from fishing in a few states such as Mississippi and Texas.[72]

Europe

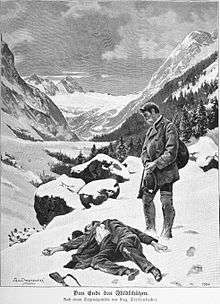

Some poachers and their violent ends, as Matthias Klostermayr (1736-1771), Georg Jennerwein (1848-1877)[12] and Pius Walder (1952 -1982) gained notoriety and had a strong cultural impact till the present. Poaching was being used then as a dare. It had a certain erotic connotation, as e.g. in Franz Schubert's Hunter's love song, (1828, D 909). The lyrics of Franz von Schobers connected unlimited hunting with the pursuit of love. Further poaching related legends and stories include the 1821 opera Freischütz till Wolfgang Franz von Kobell's 1871 story about the Brandner Kasper, a Tegernsee locksmith and poacher achieving a special deal with the grim reaper [5].

While poachers had strong local support until the early 20th century, Walder's case showed a significant change in attitudes. Urban citizens still had some sympathy for the hillbilly rebel, while the local community were much less in favor.[74]

See also

- Cruelty to animals

- Federal and state environmental relations

- Game law

- Game preservation

- Ivory trade

- Tiger poaching in India

- Wildlife trade

Notes

- ↑ Although the Duke of Gumby is probably a fictitious entity since there is no accessible record of him, the plaque may have had some deterrent effect.

References

- ↑ Webster, N. (1968). Websters New 20th Century dictionary of the English Language (2nd ed.). Cleveland: World Publishing Company. p. 1368. Random House (2001). Random House Webster's unabridged dictionary (2nd, unabridged ed.). New York: Random House. p. 1368. ISBN 0-375-42599-3. World Book Inc. (2005). "Chic=Poaching". World book encyclopedia. 15, P. Springfield: Merriam-Webster, Inc. p. 5871. McKean, E. (ed.) (2005). "Poaching". The new Oxford American dictionary. New York: Oxford University Press. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. (2010). Poaching (15th ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- 1 2 Krauss, Marita (1997-01-01). Herrschaftspraxis in Bayern und Preussen im 19. Jahrhundert: ein historischer Vergleich (in German). Campus Verlag. pp. 346 ff. ISBN 9783593358499.

- ↑ August, R. (1993). "Cowboys v. Rancheros: The Origins of Western American Livestock Law". Southwestern Historical Quarterly. Austin: Texas State Historical Association. 96 (4): 457–490.

- ↑ Power Bratton, S (1985). "Effects of disturbance by visitors on two woodland orchid species in Great Smoky Mountains National Park, USA". Biological Conservation. 31 (3): 211–227. doi:10.1016/0006-3207(85)90068-0.

- 1 2 3 Muth, R. M.; Bowe, Jr. (1998). "Illegal harvest of renewable natural resources in North America: Toward a typology of the motivations for poaching". Society & Natural Resources. 11 (1): 9–24. doi:10.1080/08941929809381058.

- ↑ Dietrich, C.; Columbini,, D. (2010). "Plant Poaching". Missouri Department of Conservation. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- ↑ Tripney, Mark. "Soils: poaching". www.fwi.co.uk. Farmers Weekly Academy. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- ↑ "Soil management standards for farmers". www.gov.uk. UK Environment Agency. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- ↑ Cuttle, S.P. (2008). "Impacts of Pastoral Grazing on Soil Quality". In McDowell, Richard W. Environmental Impacts of Pasture-based Farming. Centre for Agriculture and Biosciences International. pp. 36–38. ISBN 978-1-84593-411-8. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- ↑ Girtler, Roland (1998-01-01). Wilderer: Rebellen in den Bergen (in German). Böhlau Verlag Wien. ISBN 9783205988236.

- 1 2 3 4 "Rebellen der Berge (Rebels of the mountains)". www.bayerische-staatszeitung.de. Bayerische Staatszeitung. 2014. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ↑ Zückert, Hartmut (2003-01-01). Allmende und Allmendaufhebung: vergleichende Studien zum Spätmittelalter bis zu den Agrarreformen des 18./19. Jahrhunderts (in German). Lucius & Lucius DE. ISBN 9783828202269.

- ↑ "SEHEPUNKTE - Rezension von: Ebersberg oder das Ende der Wildnis - Ausgabe 4 (2004), Nr. 2, review of Rainer Beck: Ebersberg oder das Ende der Wildnis (Ebersberg and the end of wilderness), 2003". www.sehepunkte.de. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- 1 2 Freitag, Winfried (2013). "Wilderei – Historisches Lexikon Bayerns, poaching entry in the Bavarian historical encyclopedia". www.historisches-lexikon-bayerns.de. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ↑ McKean, E. (ed.) (2005). "Poaching". The new Oxford American dictionary. New York: Oxford University Press. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- ↑ Merriam-Webster, Inc. (2003). "Poaching". The Merriam-Webster Unabridged Dictionary. Springfield: Merriam-Webster, Inc. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- ↑ Wrottesley, G. (1884). "Staffordshire Forest Pleas: Introduction". Staffordshire Historical Collections. 5 (1): 123–135.

- ↑ Budé, G. (1861). Traitte de la vénerie. Auguste Aubry, Paris. Reported by Sir Walter Scott, The Fortunes of Nigel, Ch. 31: "The knave deer-stealers have an apt phrase, Non est inquirendum unde venit venison"; Henry Thoreau, and Simon Schama, Landscape and Memory, 1995:137, reporting William Gilpin, Remarks on Forest Scenery.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Musgrave, R. S., Parker, S. and Wolok, M. (1993). Status of Poaching in the United States – Are We Protecting Our Wildlife? Natural Resources Journal 33 (4): 977–1014.

- 1 2 3 Oldfield, S. (ed.) (2002). The Trade in Wildlife: Regulation for Conservation. Earthscan Publications Ltd., London.

- ↑ Eliason, S (2003). "Illegal hunting and angling: The neutralization of wildlife law violations". Society & Animals. 11 (3): 225–244. doi:10.1163/156853003322773032.

- ↑ Green, G. S. (2002). "The other criminalities of animal freeze-killers: Support for a generality of deviance". Society & Animals. 10 (1): 5–30. doi:10.1163/156853002760030851.

- 1 2 3 Lindsey, P., Balme, G., Becker, M., Begg, C., Bento, C., Bocchino, C., Dickman, A., Diggle, R., Eves, H., Henschel, P., Lewis, D., Marnewick, K., Mattheus, J., McNutt, J. W., McRobb, R., Midlane, N., Milanzi, J., Morley, R., Murphree, M., Nyoni, P., Opyene, V., Phadima, J., Purchase, N., Rentsch, D., Roche, C., Shaw, J., van der Westhuizen, H., Van Vliet, N., Zisadza, P. (2012). Illegal hunting and the bush-meat trade in savanna Africa: drivers, impacts and solutions to address the problem. Panthera, Zoological Society of London, Wildlife Conservation Society report, New York.

- ↑ Harvey, Gemima (1 October 2015). "Indigenous Communities and Biodiversity". The Diplomat.

- ↑ Smith, Oliver (01 Oct 2010). "Tourists urged to boycott Botswana". The Telegraph (London).

- ↑ Weisheit, R. A.; Falcone, D. N.; Wells, L. E. (1994). Rural Crime and Policing (PDF). U.S. Department of Justice: Office of Justice Programs:National Institute of Justice. Retrieved 9 August 2013.

- ↑ Forsyth, C. J.; Gramling, R.; Wooddell, G. (1998). "The game of poaching: Folk crimes in southwest Louisiana". Society & Natural Resources. 11 (1): 25–38. doi:10.1080/08941929809381059.

- ↑ Banks, D., Lawson, S., Wright, B. (eds.) (2006). Skinning the Cat: Crime and Politics of the Big Cat Skin Trade. Environmental Investigation Agency, Wildlife Protection Society of India

- ↑ Milliken, T. and Shaw, J. (2012). The South Africa – Viet Nam Rhino Horn Trade Nexus: A deadly combination of institutional lapses, corrupt wildlife industry professionals and Asian crime syndicates. TRAFFIC, Johannesburg, South Africa.

- 1 2 3 MacColl, Andrew; Wilfred, Paul. "Local Perspectives on Factors Influencing the Extent of Wildlife Poaching for Bushmeat in a Game Reserve, Western Tanzania". International Journal of Conservation Science.

- 1 2 Nyhus, Philip J. (2010). Tigers of the World (2nd Edition). Academic Press. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-8155-1570-8.

- ↑ "Elephant Poaching: CITES Failure to Combat the Growth in Chinese Demand for Ivory". Virginia Environmental Law Journal.

- 1 2 "Public attitude toward tiger farming and tiger conservation in Beijing, China.". Animal Conservation.

- ↑ Redford, Kent (June 1992). "The Empty Forest" (PDF). BioScience. 42 (6): 412–422. doi:10.2307/1311860.

- ↑ Dobson, A. and Lynes, L. (2008). How does poaching affect the size of national parks? Trends in Ecology and Evolution 23(4): 177–180.

- ↑ Georges-Courbot, M. C.; Sanchez, A.; Lu, C. Y.; Baize, S.; Leroy, E.; Lansout-Soukate, J.; Tévi-Bénissan, C.; Georges, A. J.; Trappier, S. G.; Zaki, S. R.; Swanepoel, R.; Leman, P. A.; Rollin, P. E.; Peters, C. J.; Nichol, S. T.; Ksiazek, T. G. (1997). "Isolation and phylogenetic characterization of Ebola viruses causing different outbreaks in Gabon". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 3 (1): 59–62. doi:10.3201/eid0301.970107. PMC 2627600

. PMID 9126445.

. PMID 9126445. - ↑ Bell, D.; Roberton, S.; Hunter, P. R. (2004). "Animal origins of SARS coronavirus: possible links with the international trade in small carnivores". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences. 359 (1447): 1107–1114. doi:10.1098/rstb.2004.1492.

- ↑ Wolfe, N. D., Heneine, W., Carr, J. K., Garcia, A. D., Shanmugam, V., Tamoufe, U., Torimiro, J. N., Prosser, A. T., Lebreton, M., Mpoudi-Ngole, E., McCutchan, F. E., Birx, D. L., Folks, T. M., Burke, D. S., Switzer, W. M. (2005). Emergence of unique primate T-lymphotropic viruses among central African bushmeat hunters. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 102 (22): 7994–7999.

- ↑ Keele, B. F.; Van Heuverswyn, F.; Li, Y.; Bailes, E.; Takehisa, J.; Santiago, M. L.; Bibollet-Ruche, F.; Chen, Y.; Wain, L. V.; Liegeois, F.; Loul, S.; Ngole, E. M.; Bienvenue, Y.; Delaporte, E.; Brookfield, J. F.; Sharp, P. M.; Shaw, G. M.; Peeters, M.; Hahn, B. H. (2006). "Chimpanzee reservoirs of pandemic and nonpandemic HIV-1". Science. 313: 523–526. doi:10.1126/science.1126531. PMC 2442710

. PMID 16728595.

. PMID 16728595. - ↑ Survival International Poaching Survival International Charitable Trust, London.

- ↑ Survival International (2015). Tribespeople illegally evicted from ‘Jungle Book’ tiger reserve. Survival International Charitable Trust, London.

- ↑ Survival International (2015). Tiger Reserves, India. Survival International Charitable Trust, London.

- ↑ Guynup, S. (2014). A Concise History of Tiger Hunting in India. National Geographic

- ↑ Corry, Stephen (7 February 2015). "Wildlife Conservation Efforts Are Violating Tribal Peoples’ Rights". Deep Green Resistance News Service.

- ↑ Pederson, Stephanie. "Continued Poaching Will Result in the Degradation of Fragile Ecosystems". The International. Retrieved 2013-01-31.

- ↑ Weirum, B. K. (11 November 2007). "Will traditional Chinese medicine mean the end of the wild tiger?". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ↑ "Rhino rescue plan decimates Asian antelopes". Newscientist.com. Retrieved 2010-03-18.

- ↑ Wednesday (2008-02-13). "Traffic.org". Traffic.org. Retrieved 2014-08-08.

- ↑ "Rhino horn trade triggers extinction threat, CNN, November 2011". Cnn.com. Retrieved 2014-08-08.

- ↑ Jonathan Watts in Hong Kong (25 November 2011). "article, November 2011". London: Guardian. Retrieved 2014-08-08.

- ↑ Wildlife (8 September 2012). "Telegraph article, "Rhinos under 24 hour armed guard, Sept. 2012". London: Telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 2014-08-08.

- ↑ Randall, David; Owen, Jonathan (2012-04-29). "Slaughter of rhinos at record high". London: Independent.co.uk. Retrieved 2014-08-08.

- ↑ David Smith in Johannesburg (4 September 2012). "Rhino horn: Vietnam's new status symbol heralds conservation nightmare, Guardian September 2012". London: Guardian. Retrieved 2014-08-08.

- ↑ Gettleman, Jeffrey (3 September 2012). "Elephants Dying in Epic Frenzy as Ivory Fuels Wars and Profits". The New York Times.

- ↑ Gettleman, Jeffrey (26 December 2012). "In Gabon, Lure of Ivory Is Hard for Many to Resist". The New York Times.

- ↑ Girtler, Roland (1996-01-01). Randkulturen: Theorie der Unanständigkeit (in German). Böhlau Verlag Wien. ISBN 9783205985594.

- ↑ Angler, M. (2013). Dye and Poison Stop Rhino Poachers, Scientific American, retrieved 8 August 2013

- ↑ Dunn, M. (2012). Ex-soldier takes on poachers with hi-tech help for wildlife. Herald Sun, 21 December 2012

- ↑ Mander, D. (2013). Rise of the drones. Africa Geographic February 2013: 52–55.

- ↑ Jacobs, H. (2013). The Eco-Warrior. Australia Unlimited, 19 April 2013

- ↑ Duffy, Rosaleen (2014). "Waging a war to save biodiversity: the rise of militarized conservation". International Affairs. 90: 819–834. doi:10.1111/1468-2346.12142.

- ↑ "African Elephants May Be Extinct By 2020 Because People Keep Eating With Ivory Chopsticks". huffingtonpost.com. 30 July 2014.

- ↑ Strategies for success in the ivory war, The Guardian, Paula Kahumbu, 2015

- ↑ "U.S. Ivory Crush" (PDF). U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. November 2013. Retrieved 2014-02-01.

- ↑ "In Global First, Philippines to Destroy Its Ivory Stock". National Geographic. 2013-06-18. Retrieved 2014-02-01.

- ↑ "China Crushes Six Tons of Confiscated Elephant Ivory". National Geographic. 2014-01-06. Retrieved 2014-02-01.

- ↑ "China crushes six tons of ivory". The Guardian. 2014-01-06. Retrieved 2014-02-01.

- ↑ "Poachers and Snobs: Demand for Rarity and the Effects of Anti-Poaching Policies.". Wiley Periodicals Inc.

- ↑ Jones, M. (2001). Animal robots help enforce hunting laws. Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, 2 April 2001.

- ↑ Neal, Meghan. "Poachers Are Still Getting Duped Into Shooting Robot Deer". Motherboard. Vice. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- ↑ "News Tribune". News Tribune. 2005-11-07. Retrieved 2010-03-18.

- ↑ Bauer, Dinesh (2013). "Leonhard Pöttinger | Berg und Totschlag (Poettinger - mountain and murder)". bergundtotschlag.wordpress.com. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ↑ Roland Girtler: Wilderer – Soziale Rebellen in den Bergen. Böhlau, Wien 1998, ISBN 3-205-98823-X.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Poaching. |

- Mediastorm: Black Market, published 2007

- Environmental Investigation Agency

- Environmental Investigation Agency USA

- Project Gutenberg: The Confessions of a Poacher – Personal account of a real poacher (1890).

- True Poaching Stories within the Scottish Highlands

- International Anti-Poaching Foundation

- The Rhino Rescue Project

- Rhino – UAV

- The hunter's website for bear hunting: Hunting Laws Resource – List of official State Government websites of wildlife divisions or departments

- Market size of the illegal trade in animals

- Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting Poaching Paradise (Video)

- Chengeta Wildlife