Pillars of Hercules

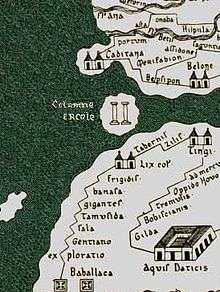

The Pillars of Hercules (Latin: Columnae Herculis, Greek: Ἡράκλειοι Στῆλαι, Arabic: أعمدة هرقل, Spanish: Columnas de Hércules) was the phrase that was applied in Antiquity to the promontories that flank the entrance to the Strait of Gibraltar. The northern Pillar is the Rock of Gibraltar (part of the British overseas territory of Gibraltar). A corresponding North African peak not being predominant, the identity of the southern Pillar has been disputed throughout history,[1] with the two most likely candidates being Monte Hacho in Ceuta and Jebel Musa in Morocco.

History

According to Greek mythology adopted by the Etruscans and Romans, when Hercules had to perform twelve labours, one of them (the tenth) was to fetch the Cattle of Geryon of the far West and bring them to Eurystheus; this marked the westward extent of his travels. A lost passage of Pindar quoted by Strabo was the earliest traceable reference in this context: "the pillars which Pindar calls the 'gates of Gades' when he asserts that they are the farthermost limits reached by Heracles."[2] Since there has been a one-to-one association between Heracles and Melqart since Herodotus, the "Pillars of Melqart" in the temple near Gades/Gádeira (modern Cádiz) have sometimes been considered to be the true Pillars of Hercules.[3]

According to Plato's account, the lost realm of Atlantis was situated beyond the Pillars of Hercules, in effect placing it in the realm of the Unknown. Renaissance tradition says the pillars bore the warning Ne plus ultra (also Non plus ultra, "nothing further beyond"), serving as a warning to sailors and navigators to go no further.

According to some Roman sources,[4] while on his way to the garden of the Hesperides on the island of Erytheia, Hercules had to cross the mountain that was once Atlas. Instead of climbing the great mountain, Hercules used his superhuman strength to smash through it. By doing so, he connected the Atlantic Ocean to the Mediterranean Sea and formed the Strait of Gibraltar. One part of the split mountain is Gibraltar and the other is either Monte Hacho or Jebel Musa. These two mountains taken together have since then been known as the Pillars of Hercules, though other natural features have been associated with the name.[5] Diodorus Siculus,[6] however, held that instead of smashing through an isthmus to create the Straits of Gibraltar, Hercules narrowed an already existing strait to prevent monsters from the Atlantic Ocean from entering the Mediterranean Sea.

Pillars as a portal

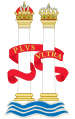

The columns as depicted in the Spanish coat of arms.

The columns as depicted in the Spanish coat of arms.

The Pillars appear as supporters of the coat of arms of Spain, originating in the impresa of Spain's sixteenth century king Charles I, who was also the Holy Roman Emperor as Charles V. It bears the motto Plus Ultra, Latin for further beyond, implying that the pillars were a gateway.

.svg.png)

Phoenician connection

Beyond Gades, several important Mauritanian colonies (in modern-day Morocco) were founded by the Phoenicians as the Phoenician merchant navy pushed through the Pillars of Hercules and began constructing a series of bases along the Atlantic coast starting with Lixus in the north, then Chellah and finally Mogador.[7]

Near the eastern shore of the island of Gades/Gadeira (modern Cádiz, just beyond the strait) Strabo describes[8] the westernmost temple of Tyrian Heracles, the god with whom Greeks associated the Phoenician and Punic Melqart, by interpretatio graeca. Strabo notes[9] that the two bronze pillars within the temple, each eight cubits high, were widely proclaimed to be the true Pillars of Hercules by many who had visited the place and had sacrificed to Heracles there. But Strabo believes the account to be fraudulent, in part noting that the inscriptions on those pillars mentioned nothing about Heracles, speaking only of the expenses incurred by the Phoenicians in their making. The columns of the Melqart temple at Tyre were also of religious significance.

The Pillars in Syriac geography

Syriac scholars were aware of the Pillars through their efforts to translate Greek scientific works into their language as well as into Arabic. The Syriac compendium of knowledge known as Ktaba d'ellat koll 'ellan. "The Cause of all Causes", is unusual in asserting that there were three, not two, columns[10]

Dante's Inferno

In Inferno XXVI Dante Alighieri mentions Ulysses in the pit of the Fraudulent Counsellors and his voyage past the Pillars of Hercules. Ulysses justifies endangering his sailors by the fact that his goal is to gain knowledge of the unknown. After five months of navigation in the ocean, Ulysses sights the mountain of Purgatory but encounters a whirlwind from it that sinks his ship and all on it for their daring to approach Purgatory while alive, by their strength and wits alone.

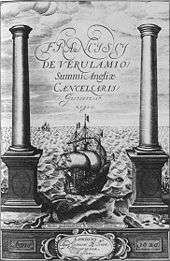

Sir Francis Bacon's Novum Organum

The Pillars appear prominently on the engraved title page of Sir Francis Bacon's Instauratio Magna ("Great Renewal"), 1620, an unfinished work of which the second part was his influential Novum Organum. The motto along the base says Multi pertransibunt et augebitur scientia ("Many will pass through and knowledge will be the greater"). The image was based on the use of the pillars in Spanish and Habsburg propaganda.

In architecture

On the Spanish coast at Los Barrios are Torres de Hercules which are twin towers that were inspired by the Pillars of Hercules. These towers are the tallest buildings in Andalucía.[11]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pillars of Hercules. |

- ↑ Strabo summarizes the dispute in Geographia 3.5.5.

- ↑ Strabo, 3.5.5; the passage in Pindar has not been traced.

- ↑ Walter Burkert (1985). Greek Religion. Harvard University Press. p. 210. ISBN 978-0-674-36281-9. Retrieved 2 November 2012.

- ↑ Seneca, Hercules Furens 235ff.; Seneca, Hercules Oetaeus 1240; Pliny, Nat. Hist. iii.4.

- ↑ "Close to the Pillars there are two isles, one of which they call Hera's Island; moreover, there are some who call also these isles the Pillars." (Strabo, 3.5.3.); see also H. L. Jones' gloss on this line in the Loeb Classical Library.

- ↑ Diodorus 4.18.5.

- ↑ C. Michael Hogan, Mogador, Megalithic Portal, ed. Andy Burnham, 2007

- ↑ (Strabo 3.5.2–3

- ↑ Strabo 3.5.5–6

- ↑ Adam C. McCollum. (2012). A Syriac Fragment from The Cause of All Causes on the Pillars of Hercules. ISAW Papers, 5. .

- ↑ ‘Torres de Hercules’ in Cadiz / Spain by Rafael de la Hoz Architects (ES), Nora Schmidt, Daily Tonic, accessed 8 January 2012

Coordinates: 36°0′N 5°21′W / 36.000°N 5.350°W