Phytotherapy

Phytotherapy is a science-based medical practice based on the study of extracts of natural origin and their use as medicines or health-promoting agents.[1] It has an associated long-established scientific journal published as Phytotherapy Research.

Phytotherapy is distinct from homeopathy and anthroposophic medicine, and avoids mixing plant and synthetic bioactive substances. Phytotherapy is regarded by some as alternative medicine. The medicinal and biological effects of many plant constituents such as the alkaloids, morphine and atropine for example, have been proven through clinical studies. However there is debate about the efficacy and the place of phytotherapy in medical therapies.

Definition

Phytotherapy is a scientifically based, medical practice that uses medical evidence to produce pharmacologically active medicines. As such it cannot be grouped as a complementary or alternative medicine.[1]

A reference guide to phytotherapy Rationale Phytotherapy was first published in German in 1996 and this was published in English in 1997 as Rational Phytotherapy under the supervision of American pharmacognosist Varro Tyler.[1]

Clinical tests

In 2002, the U.S. National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health of the National Institutes of Health began funding clinical trials into the effectiveness of herbal medicine.[2] In a 2010 survey of 1000 plants, 356 had clinical trials published evaluating their "pharmacological activities and therapeutic applications" while 12% of the plants, although available in the Western market, had "no substantial studies" of their properties.[3]

Even widely used remedies may not have undergone substantial clinical testing. In a review on herbal medicine in malaria treatment, the authors found that "...better evidence from randomised clinical trials is needed before herbal remedies can be recommended on a large scale. As such trials are expensive and time consuming, it is important to prioritise remedies for clinical investigation...."[4]

Consistency

In herbal medicine, plant material that has been processed in a repeatable operation so that a discrete marker constituent is at a verified concentration is then considered standardized. Active constituent concentrations may be misleading measures of potency if cofactors are not present. A further problem is that the important constituent is often unknown. For instance St John's wort is often standardized to the antiviral constituent hypericin which is now known to be the active ingredient for antidepressant use. Other companies standardize to hyperforin or both, although there may be some 24 known possible constituents. Only a minority of chemicals used as standardization markers are known to be active constituents. Standardization has not been standardized yet: different companies use different markers, or different levels of the same markers, or different methods of testing for marker compounds. The renowned herbalist and ethnobotanist David Winston points out that whenever different compounds are chosen as 'active ingredients' for different herbs, there is a chance that suppliers will get a substandard batch (low on the chemical markers) and mix it with a batch higher in the desired marker to compensate for the difference.[5]

Quality

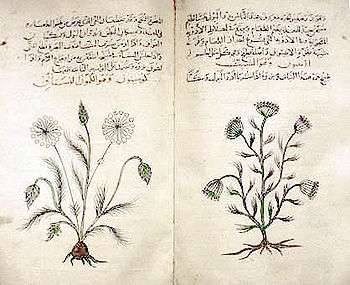

The quality of crude drugs or plant medicines depends upon a variety of factors, including the variability in the species of plant being used; the plant's growing conditions (i.e. soil, sun, climate); and the timing of harvest, post-harvest processing, and storage conditions. The quality of some plant drugs can judged by organoleptic factors (i.e. sensory properties such as the taste, color, odor or feel of the drug), or by administering a small dose of the drug and observing the effects. These conditions have been noted in historical herbals such as Culpepper's Complete Herbal[6] or The Shennong or The Divine Farmer's Materia Medica.[7]

Modern phytotherapy may use traditional methods of assessment of herbal drug quality, but more typically relies on modern processes like high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), (gas chromatography), UV/VIS (Ultraviolet/Visible spectrophotometry) or AA (atomic absorption spectroscopy). These are used to identify species, measure bacteriological contamination, assess potency and eventually create Certificates of Analysis for the material.

Quality should be overseen by either authorities ensuring Good Manufacturing Practices or regulatory agencies by the US FDA. In the United States one frequently sees comments that herbal medicine is unregulated, but this is not correct since the FDA and GMP regulations are in place. In Germany, the Commission E has produced a book of German legal-medical regulations which includes quality standards.[8]

Safety

A number of herbs are thought to be likely to cause adverse effects.[9] Furthermore, "adulteration, inappropriate formulation, or lack of understanding of plant and drug interactions have led to adverse reactions that are sometimes life threatening or lethal."[10] Although many consumers believe that herbal medicines are safe because they are "natural", herbal medicines may interact with synthetic drugs causing toxicity to the patient, may have contamination that is a safety consideration, and herbal medicines, without proven efficacy, may be used to replace medicines that have a proven efficacy.[11]

Ephedra has been known to have numerous side effects, including severe skin reactions, irritability, nervousness, dizziness, trembling, headache, insomnia, profuse perspiration, dehydration, itchy scalp and skin, vomiting, hyperthermia, irregular heartbeat, seizures, heart attack, stroke, or death.[12] Ephedra has been an object of difficulty; having legitimate medical uses, illegal uses and powerful side effects. Known and used as Mormon Tea or Indian Tea, the plant contains the potent chemicals ephedrine and pseudoephedrine. Aside from being chemicals used to create methamphetamine they have direct central nervous system (CNS) stimulant effects including high blood pressure and high heart rate. These effects have led to strokes and other CNS or cardiac issues in certain people at certain dosages. In recent years, the safety of ephedra-containing dietary supplements has been questioned by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, and the medical community as a result of reports of serious side effects and ephedra-related deaths.[13][14][15][16] However, when used appropriately by the correct people it is an effective decongestant, a bronchodilator for use in asthma and an adjuvant for the common cold.

Plants such as Comfrey[17][18] and Petasites have specific toxicity due to hepatotoxic pyrrolizidine alkaloid content.[19][20] There are other plant medicines which require caution or can interact with other medications, including St. John's wort and grapefruit.[21]

Regulation

In 1994, the U.S. Congress passed the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA), regulating labeling and sales of herbs and other supplements. Most of the 2000 U.S. companies making herbal or natural products[22] choose to market their products as food supplements that did not require substantial testing and gave no assurance of safety and efficacy. With the implementation of the Current Good Manufacturing Practices (CGMPs) for Dietary Supplements in 2007, the situation improved. Since then all US companies importing, manufacturing or selling these products must comply with Federal Register Volume 72, Number 121, to test for identity, purity and strength of all dietary supplements including herbal products, and investigate quality deviations through a Corrective and preventive action (CAPA) plan. Furthermore, the United States Pharmacopeia has incorporated more quality control monographs for herbs and supplements, which are officially accepted testing protocols by the Food and Drug Administration. New dietary supplement ingredients that were previously not marketed in the US require a product approval process.

Limitations

Many diseases have no known effective herbal treatment. One large category of such disease is cancer. According to Cancer Research UK, "there is currently no strong evidence from studies in people that herbal remedies can treat, prevent or cure cancer".[23]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Phytotherapy. |

References

- 1 2 3 "phytotherapy | medicine". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ↑ Herbal Medicine, NIH Institute and Center Resources, National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, National Institutes of Health.

- ↑ Cravotto G, Boffa L, Genzini L, Garella D (February 2010). "Phytotherapeutics: an evaluation of the potential of 1000 plants". J Clin Pharm Ther. 35 (1): 11–48. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2710.2009.01096.x. PMID 20175810.

- ↑ "Traditional herbal medicines for malaria". BMJ. 329: 1156–1159. 2004. doi:10.1136/bmj.329.7475.1156. PMC 527695

. PMID 15539672.

. PMID 15539672. - ↑ Alan Tillotson Growth, Maturity, Quality

- ↑ Culpeper's Complete Herbal by Nicholas Culpeper reprinted in 2003 by Kensington Arts Press

- ↑ The Divine Farmer's Materia Medica: A Translation of the Shen Nong Ben Cao (Blue Poppy's Great Masters Series) by Yang Shou-Zhong and Bob Flaws (translator) Blue Poppy 1998

- ↑ Making Sense of Commission E, review by Jonathan Treasure, 1999-2000.

- ↑ Talalay P. and Talalay P., "The Importance of Using Scientific Principles in the Development of Medicinal Agents from Plants", Academic Medicine, 2001, 76, 3, p238.

- ↑ Elvin-Lewis M (2001). "Should we be concerned about herbal remedies". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 75 (2-3): 141–164. doi:10.1016/S0378-8741(00)00394-9. PMID 11297844.

- ↑ Ernst E (2007). "Herbal medicines: balancing benefits and risks". Novartis Found. Symp. 282: 154–67; discussion 167–72, 212–8. doi:10.1002/9780470319444.ch11. PMID 17913230.

- ↑ Ephedra information from Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. Accessed April 11, 2007.

- ↑ Haller C, Benowitz N (2000). "Adverse cardiovascular and central nervous system events associated with dietary supplements containing ephedra alkaloids". N Engl J Med. 343 (25): 1833–8. doi:10.1056/NEJM200012213432502. PMID 11117974.

- ↑ Bent S, Tiedt T, Odden M, Shlipak M (2003). "The relative safety of ephedra compared with other herbal products". Ann Intern Med. 138 (6): 468–71. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-138-6-200303180-00010. PMID 12639079.

- ↑ "National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health Consumer Advisory on ephedra". 2004-10-01. Retrieved 2007-02-13.

- ↑ "Food and Drug Administration summary of actions regarding sale of ephedra supplements". Retrieved 2007-02-13.

- ↑ Hiller K, Loew D. 2009. Symphyti radix. In Teedrogen und Phytopharmaka, WichtlM (ed). Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft mbH Stuttgart: Stuttgart; 644–646.

- ↑ Benedek, B.; Ziegler, A.; Ottersbach, P. (2010). "Absence of mutagenic effects of a particular Symphytum officinale L. liquid extract in the bacterial reverse mutation assay". Phytotherapy Research. 24: 466–468. doi:10.1002/ptr.3000.

- ↑ Mattocks AR 1986. Chemistry and Toxicology of Pyrrolizidine Alkaloids, Academic Press: London; 391.

- ↑ Cordell, G. A.; Quinn-Beattie, M. L.; Farnsworth, N. R. (2001). "The potential of alkaloids in drug discovery". Phytotherapy Research. 15: 183–205. doi:10.1002/ptr.890.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-09-24. Winston, David. Herbal Medicine Introduction

- ↑ Whole Foods Magazine

- ↑ "Herbal medicine". Cancer Research UK. Retrieved August 2013. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help)