People's Budget

|

| |

| Presented | 29 April 1909 |

|---|---|

| Passed | 29 April 1910 |

| Parliament | 28th/29th |

| Party | Liberal Party |

| Chancellor | David Lloyd George |

| Website | Hansard |

|

‹ 1908 1911 › | |

The 1909/1910 People's Budget was a product of then British Prime Minister H. H. Asquith's Liberal government, introducing unprecedented taxes on the wealthy in Britain and radical social welfare programmes to the country's policies.

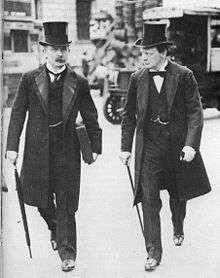

It was championed by Chancellor of the Exchequer David Lloyd George and his young ally Winston Churchill, who was then President of the Board of Trade and a fellow Liberal; called the "Terrible Twins" by certain Conservative contemporaries.[1]

Churchill's biographer, William Manchester, called the People's Budget "a revolutionary concept" because it was the first budget in British history with the expressed intent of redistributing wealth among the British public. It was a key issue of contention between the Liberal government and the Conservative-dominated House of Lords, leading to two general elections in 1910 and the enactment of the Parliament Act 1911.

Overview

The Budget was introduced in the British Parliament by David Lloyd George on 29 April 1909.[2] Lloyd George argued that the People's Budget would eliminate poverty, and commended it thus:

This is a war Budget. It is for raising money to wage implacable warfare against poverty and squalidness. I cannot help hoping and believing that before this generation has passed away, we shall have advanced a great step towards that good time, when poverty, and the wretchedness and human degradation which always follows in its camp, will be as remote to the people of this country as the wolves which once infested its forests.[3]

The budget included several proposed tax increases to fund the Liberal welfare reforms. Income tax was held at nine pence in the pound (9d, or 3.75%) on incomes less than £2,000, which was equivalent to £190,000 in today's money[4]—but a higher rate of one shilling (12d, or 5%) was proposed on incomes greater than £2,000, and an additional surcharge or "super tax" of 6d (a further 2.5%) was proposed on the amount by which incomes of £5,000 (£470,000 today[4]) or more exceeded £3,000 (£280,000 today[4]). An increase was also proposed in death duties and naval rearmament.

More controversially, the Budget also included a proposal for the introduction of complete land valuation and a 20% tax on increases in value when land changed hands.[5] Land taxes were based on the ideas of the American tax reformer Henry George. This would have had a major effect on large landowners, and the Conservative-Unionist opposition, many of whom were large landowners, had had an overwhelming majority in the Lords since the Liberal split in 1886. Furthermore, the Conservatives believed that money should be raised through the introduction of tariffs on imports, which would benefit British industry and trade within the Empire, and raise revenue for social reforms at the same time (protectionism); but this was also unpopular as it would have meant higher prices on imported food. According to economic theory, such tariffs would have been very beneficial for landowners, especially tariffs on agricultural produce, but the costs to ordinary consumers would have exceeded the gains to these landowners. (see Corn Laws).

Constitutional stand-off

The Northcliffe Press (who published both The Times and the Daily Mail) urged rejection of the budget to give tariff reform a chance.[6] There were many public meetings, some of them organised by dukes, which portrayed the budget as the thin end of the socialist wedge. Lloyd George gave a speech at Limehouse (July 1909) in which he said that "a fully-equipped duke cost as much to keep up as two dreadnoughts (battleships)"– but was "much less easy to scrap".[7] The Conservatives wanted to force an election by rejecting the budget.[8]

The Lords were entitled by convention to reject, but not to amend, a money bill, but had not rejected a budget for two centuries. Originally the budget had included only annual renewals of existing taxes – any amendment to taxes was part of a separate Act. This ended in 1861 (William Ewart Gladstone was Chancellor at the time) when the Lords rejected the repeal of paper duties – which would have benefited new cheaper newspapers, aimed at men who hoped soon to be given the right to vote, at the expense of existing papers. From then on, all taxes were included in the Finance Bill, and no such bill had been rejected, not even the controversial introduction of death duties by Sir William Harcourt in 1894.[9]

Despite the King's private urgings that the budget be passed to avoid a crisis,[10] the House of Lords vetoed the new budget on 30 November 1909, although they were clear that they would pass it as soon as the Liberals obtained an electoral mandate for it.[11] The Liberals countered by proposing to reduce the power of the Lords. This was the main issue of the general election in January 1910, setting the stage for a tremendous showdown, which Lloyd George and Churchill relished.

Despite the heated rhetoric, opinion in the country was divided.[12] The Unionists with 47% of the votes were outpolled by the Liberals and their Labour allies. The outcome was a hung parliament, with the Liberals relying on Labour and the Irish Parliamentary Party for their majority.

As the price for their continued support, the Irish nationalist MPs demanded measures to remove the Lords' veto so that they could no longer block Irish Home Rule. They even threatened to vote down the Budget in the House of Commons (Irish Nationalists favoured tariff reform and abhorred the planned increase in whiskey duty[13]) until Asquith pledged to introduce such measures.

As they had promised, the Lords accepted the Budget on 28 April 1910—a year to the day after its introduction[14]—when the land tax proposal was dropped, but contention between the government and the Lords continued until the second general election in December 1910, when the Unionists were again outpolled by their combined opponents. The result was another hung parliament, with the Liberals again relying on Labour and the Irish Party. Nonetheless, the Lords passed the Parliament Act 1911 when faced with the threat, obtained from a narrowly convinced new King (George V), that it would be acceptable to flood the House of Lords with hundreds of new Liberal peers to give that party a majority or near-majority there.

See also

References

- ↑ Geoffrey Lee - The People's Budget: An Edwardian Tragedy

- ↑ Raymond, E. T. (1922). Mr. Lloyd George. George H. Doran company. p. 118.

- ↑ "The National Archives Learning Curve | Britain 1906-18 | Achievements of Liberal Welfare Reforms: Gallery 2". Learningcurve.gov.uk. Retrieved 2010-01-24.

- 1 2 3 UK CPI inflation numbers based on data available from Gregory Clark (2016), "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)" MeasuringWorth.

- ↑ Magnus 1964, p527

- ↑ Magnus 1964, p532

- ↑ Magnus 1964, p527

- ↑ Magnus 1964, p534

- ↑ Magnus 1964, p530

- ↑ Magnus 1964,p 536

- ↑ Palmer, Alan; Veronica (1992). The Chronology of British History. London: Century Ltd. pp. 342–343. ISBN 0-7126-5616-2.

- ↑ Magnus 1964, p546

- ↑ Magnus 1964, p548

- ↑ Raymond, E. T. (1922). Mr. Lloyd George. George H. Doran company. p. 136.

Bibliography

- William Manchester, The Last Lion: Winston Spencer Churchill, Visions of Glory 1874-1932, pp. 408–409 (1st Edition); 1983; ISBN 0-316-54503-1;

- Magnus, Philip (1964), King Edward The Seventh, London: John Murray, ISBN 0140026584