Peak District

| Peak District National Park | |

|---|---|

| "The Peak" | |

|

IUCN category V (protected landscape/seascape) | |

|

A view of Mam Tor, Peak District National Park | |

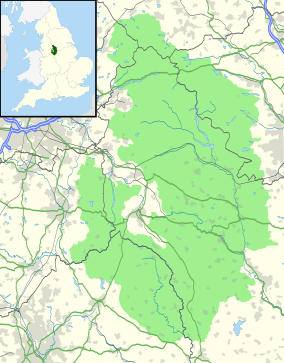

Peak District National Park (shaded green) within England | |

| Location | England |

| Nearest town |

Derbyshire Cheshire Greater Manchester Staffordshire South Yorkshire West Yorkshire |

| Coordinates | 53°21′N 1°50′W / 53.350°N 1.833°W |

| Area | 555 sq mi (1,440 km2) |

| Designated | 17 April 1951 |

| Visitors | Over 10 million[1] |

| Administrator | National Park Authority |

| Website |

www |

The Peak District is an upland area in England at the southernmost end of the Pennines. It falls mostly in northern Derbyshire but also includes parts of Cheshire, Greater Manchester, Staffordshire and Yorkshire.

An area of great diversity, it is split into the northern Dark Peak, where most of the moorland is found and whose geology is gritstone, and the southern White Peak, where most of the population lives and whose geology is mainly limestone.

The Peak District National Park became the first national park in the United Kingdom in 1951.[2] With its proximity to the cities of Manchester and Sheffield and easy access by road and rail, it attracts millions of visitors every year.[3][4]

Geography

The Peak District forms the southern end of the Pennines and much of the area is uplands above 1,000 feet (300 m), with a high point on Kinder Scout of 2,087 ft (636 m).[5] Despite its name, the landscape generally lacks sharp peaks, being characterised by rounded hills and gritstone escarpments (the "edges"). The area is surrounded by major conurbations, including Huddersfield, Manchester, Sheffield, Derby and Stoke-on-Trent.

The National Park covers 555 square miles (1,440 km2)[6] of Derbyshire, Staffordshire, Cheshire, Greater Manchester and South and West Yorkshire, including the majority of the area commonly referred to as the Peak. Its northern limits lie along the A62 road between Marsden and Meltham, north east of Oldham, while its southernmost point is on the A52 road on the outskirts of Ashbourne in Derbyshire. The Park boundaries were drawn to exclude large built-up areas and industrial sites from the park; in particular, the town of Buxton and the adjacent quarries are located at the end of the Peak Dale corridor, surrounded on three sides by the Park.

The town of Bakewell and numerous villages are included within the boundaries, as is much of the (non-industrial) west of Sheffield. As of 2010, it is the fifth largest National Park in England and Wales.[7] In the UK, the designation "National Park" means that there are planning restrictions to protect the area from inappropriate development and a Park Authority to look after it, but does not imply that the land is owned by the government, or that it is uninhabited.

12% of the Peak District National Park is owned by the National Trust, a charity which aims to conserve historic and natural landscapes. It does not receive government funding.[8] The three Trust estates (High Peak, South Peak and Longshaw) include the ecologically or geologically significant areas of Bleaklow, Derwent Edge, Hope Woodlands, Kinder Scout, Leek and Manifold, Mam Tor, Dovedale, Milldale and Winnats Pass.[9][10][11] The Peak District National Park Authority directly owns around 5%, and other major landowners include several water companies.[12]

Geology

The Peak District is formed almost exclusively from sedimentary rocks dating from the Carboniferous period. They comprise the Carboniferous Limestone, the overlying Gritstone and finally the Coal Measures, though the latter occur only on the extreme margins of the area. In addition there are infrequent outcrops of igneous rocks including lavas, tuffs and volcanic vent agglomerates.[13]

The general geological structure of the Peak District is that of a broad dome (see image below), whose western margins have been most intensely faulted and folded. Uplift and erosion have effectively sliced the top off the dome to reveal a concentric outcrop pattern with Coal Measures rocks on the eastern and western margins, Carboniferous Limestone at the core and with rocks of Millstone Grit outcropping between these two. The southern edge of the dome is overlain by sandstones of Triassic age though these barely impinge upon the National Park.

The central and southern section of the Peak District, where the Carboniferous Limestone is found at or near the surface, is known as the White Peak in contrast to the Dark Peak, which is characterised by Millstone Grit outcrops and broad swathes of moorland.

Earth movements after the Carboniferous period resulted in the up-doming of the area and, particularly in the west, the folding of the rock strata along north–south axes. The region was raised in a north–south line which resulted in this dome-like shape[14] and the shale and sandstone were worn away until limestone was exposed. At the end of this period, the Earth's crust sank here which led to the area being covered by sea, depositing a variety of new rocks.[15]

Some time after its deposition, mineral veins were formed in the limestone. These veins and rakes have been mined for lead since Roman times.[15]

The Peak District was covered by ice during at least one of the ice ages of the last 2 million years (probably the Anglian glaciation of around 450,000 years ago) as evidenced by the patches of glacial till or boulder clay that can be found across the area. It was not covered by ice during the last glacial period, which peaked around 20,000–22,000 years ago. A mix of Irish Sea and Lake District ice abutted against its western margins. Glacial meltwaters eroded a complex of sinuous channels along this margin of the Peak District during this period.[16]

Glacial meltwaters also contributed to the formation and development of many of the caves in the limestone area.[17] Wild animal herds roamed the area, and their remains have been found in several of the local caves.[15]

The different types of rock that lie beneath the soil strongly influence the landscape; they determine the type of vegetation that will grow, and ultimately the type of animal that will inhabit the area.[18] Limestone has fissures and is soluble in water, therefore rivers have been able to carve deep, narrow valleys. These rivers then often find a route underground, creating cave systems. Millstone Grit on the other hand is insoluble but porous, so it absorbs water which often seeps through the grits, until it meets the less porous shales beneath, creating springs when it reaches the surface again. The shales are friable and easily attacked by frost, so they form areas that are vulnerable to landslides, as on Mam Tor.[14]

Rivers

The high moorland plateau of the Dark Peak and the high ridges of the White Peak are the sources of many rivers. In a report for the Manchester Corporation, the engineer John Frederick Bateman wrote in 1846:

Within ten or twelve miles of Manchester, and six or seven miles from the existing reservoirs at Gorton, there is this tract of mountain land abounding with springs of the purest quality. Its physical and geological features offer such peculiar features for the collection, storage and supply of water for the use of the towns in the plains below that I am surprised that they have been overlooked.

He was referring to Longdendale, and the upper valley of the River Etherow. The western side of the Peak District is drained by the rivers Etherow, Goyt, and Tame, which are tributaries of the River Mersey. The north east is drained by tributaries of the River Don, itself a tributary of the Yorkshire Ouse. Of the tributaries of the River Trent, that drain the south and east, the River Derwent is the most prominent. It rises in the Peak District on Bleaklow just east of Glossop and flows through the Upper Derwent Valley with its three reservoirs, the Howden Reservoir, Derwent Reservoir and Ladybower Reservoir.[20] The River Noe and the River Wye are tributaries.[21] The River Manifold[22] and River Dove,[23] rivers of the south west whose sources are on Axe Edge Moor, also flow into the Trent, while the River Dane[24] flows into the River Weaver.

Ecology

The gritstone and shale of the Dark Peak supports heather moorland and blanket bog environments, with rough sheep pasture and grouse shooting being the main land uses. The limestone plateaux of the White Peak are more intensively farmed, with mainly dairy usage of improved pastures. Some sources also recognise the South West Peak (near Macclesfield) as a third type of area, with intermediate characteristics.[25]

Woodland forms around 8% of the Peak National Park.[12] Natural broad-leaved woodland is found in the steep-sided, narrow dales of the White Peak and the deep cloughs of the Dark Peak, while reservoir margins often have coniferous plantations.

Lead rakes, the spoil heaps of ancient mines, form another distinctive habitat in the White Peak, supporting a range of rare metallophyte plants, including the spring sandwort (Minuartia verna; also known as leadwort), alpine pennycress (Thlaspi caerulescens) and mountain pansy (Viola lutea).[26]

Climate

With the majority of the area being in excess of 1,000 feet (300 m) above sea level,[27] and being situated to the west of the country with a latitude of 53°N, the Peak District experiences a relatively high amount of rainfall each year compared to the rest of England and Wales, averaging 40.35 inches (1,025 mm) in 1999. The Dark Peak tends to receive more rainfall each year in comparison to the White Peak as it is higher in altitude. This higher rainfall does not seem to affect the area's temperature, as it averages the same as England and Wales at 10.3 °C (50.5 °F).[28]

During the 1970s, the Dark Peak regularly recorded over 70 days of snowfall each year. Since then this number has decreased markedly. Frost cover is seen for 20–30% of the winter on the moors of the Dark Peak and for 10% on the White Peak,[29] and the hills of the National Park still see periods of long continuous snow cover in some winters. For example, a snowfall in mid-December 2009 on the summits of some of the hills created snow patches that lasted in some cases until May 2010. In that same winter, some of the area's passes, such as the A635 (Saddleworth Moor) and A57 (Snake Pass), were closed because of lying snow for almost a month.

The Moorland Indicators of Climate Change Initiative was set up in 2008 to collect data on climate change in the area. Students investigated the interaction between people and the moorlands, and their overall effect on climate change, to discover whether the moorlands are a net carbon sink or source, based on the fact that upland areas of Britain are a significant global carbon store in the form of peat. Human interaction in terms of direct erosion and fire as well as the effects of global warming are the major variables that they considered.[30]

Economy

Tourism is the major local employment for Park residents (24%), with manufacturing industries (19%) and quarrying (12%) also being important. 12% are employed in agriculture.[31] The cement works at Hope is the largest single employer within the Park.[32] Tourism is estimated to provide 500 full-time jobs, 350 part-time jobs and 100 seasonal jobs.[33]

Limestone is the most important mineral quarried, mainly for roads and cement; shale is extracted for cement at Hope, and several gritstone quarries are worked for housing.[32] Lead mining is no longer economic, but fluorite, baryte and calcite are extracted from lead veins, and small-scale Blue John mining occurs at Castleton.

The springs at Buxton and Ashbourne are exploited to produce bottled mineral water, and many of the plantations are managed for timber. Other manufacturing industries of the area are varied; they include David Mellor's cutlery factory in Hathersage, Ferodo brake linings in Chapel-en-le-Frith and electronic equipment in Castleton. There are approximately 2,700 farms in the National Park, most of them under 40 hectares (99 acres) in area. 60% of farms are believed to be run on a part-time basis where the farmer has a second job.[33]

History

Early history

The Peak District has been inhabited from the earliest periods of human activity, as is evidenced by occasional finds of Mesolithic flint artefacts and by palaeoenvironmental evidence from caves in Dovedale and elsewhere. There is also evidence of Neolithic activity, including some monumental earthworks or barrows (burial mounds) such as that at Margery Hill.[34] In the Bronze Age the area was well populated and farmed, and evidence of these people survives in henges such as Arbor Low near Youlgreave, or the Nine Ladies Stone Circle at Stanton Moor.[35]

In the same period, and on into the Iron Age, a number of significant hillforts such as that at Mam Tor were created. Roman occupation was sparse but the Romans certainly exploited the rich mineral veins of the area, exporting lead from the Buxton area along well-used routes. There were Roman settlements, including one at Buxton which was known to them as "Aquae Arnemetiae" in recognition of its spring,[36] dedicated to the local goddess.

Theories as to the derivation of the Peak District name include the idea that it came from the Pecsaetan or peaklanders, an Anglo-Saxon tribe who inhabited the central and northern parts of the area from the 6th century AD when it fell within the large Anglian kingdom of Mercia.[37][38]

Mining and quarrying

In medieval and early modern times the land was mainly agricultural, as it still is today, with sheep farming, rather than arable, the main activity in these upland holdings. However, from the 16th century onwards the mineral and geological wealth of the Peak became increasingly significant. Not only lead, but also coal, fluorite, copper (at Ecton), zinc, iron, manganese and silver have all been mined here.[39] Celia Fiennes, describing her journey through the Peak in 1697, wrote of

... those craggy hills whose bowells are full of mines of all kinds off black and white and veined marbles, and some have mines of copper, others tinn and leaden mines, in w[hi]ch is a great deale of silver.

Coal measures occur on the western and the eastern fringes of the Peak District, and evidence of past workings can be found from Glossop down to The Roaches, and from Stocksbridge to Baslow. Mining started in medieval times and was at its most productive in the 18th and early 19th centuries, in some cases continuing into the early 20th century. The earliest mining took place at and close to outcrops and miners eventually followed the seams deeper underground as the beds dipped beneath hillsides. At Goyt's Moss and Axe Edge, deep seams were worked and steam engines raised the coal and dewatered the mines.[41] Coal from the eastern mines was used in lead smelting, and coal from the western mines for lime burning.[42]

Lead mining peaked in the 17th and 18th centuries; high concentrations of lead have been found in the area dating back from this period, as well as discovering peat on Kinder Scout suggesting that lead smelting occurred.[43] Lead mining began to decline from the mid-19th century, with the last major mine closing in 1939, though lead remains a by-product of fluorite, baryte and calcite mining.[26] Not all mines were deep underground; Bell pits were a cheap and easy way at getting at an ore that lay close to the surface of flat land. A shaft was sunk into the ore and enlarged at the bottom for extraction. The pit was then enlarged further until it became unsafe or worked out, then another pit would be sunk adjacent to the existing one.[43]

Fluorite or fluorspar is called Blue John in the Peak District, the name allegedly coming from the French Bleu et Jaune which describes the colour of the bandings. Blue John is now scarce, and only a few hundred kilograms are mined each year for ornamental and lapidary use. The Blue John Cavern in Castleton is a show cave; mining still takes place in the nearby Treak Cliff Cavern.[44]

Industrial limestone quarrying for the manufacture of soda ash started in the Buxton area as early as 1874. In 1926 this operation became part of ICI.[45] Large-scale limestone and gritstone quarries flourished as lead mining declined, and remain an important if contentious industry in the Peak. Twelve large limestone quarries operate in the Peak; Tunstead near Buxton is one of the largest quarries in Europe.[46] Total limestone output was substantial: at the 1990 peak, 8.5 million tonnes was quarried.[32]

Introduction of textiles

Textiles have been exported from the Peak for hundreds of years. Even as early as the 14th century, the area traded in unprocessed wool.[47] There was a number of skilled hand spinners and weavers in the area. By the 1780s, inventors such as Richard Arkwright developed machinery to produce textiles more quickly and to a higher standard. The early mills were narrow and low in height, of light construction, powered by water wheels and containing small machines. Interior lighting was by daylight, and ceiling height was only 6 to 8 feet (1.8 to 2.4 m). These Arkwright type mills are about 9 feet (2.7 m) wide.[48] The Peak District was the ideal location, with its rivers and humid atmosphere. The local pool of labour was quickly exhausted and the new mills such as Litton Mill and Cressbrook Mill in Millers Dale brought in children as young as four from the workhouses of London as apprentices.[49]

With the advance of technology, the narrow Derbyshire valleys became unsuited to the larger steam driven mill, but the Derbyshire mills remained, and continued to trade in finishing and niche products. The market town of Glossop benefitted from the textile industry. The town's economy was linked closely with a spinning and weaving tradition which had evolved from developments in textile manufacture during the Industrial Revolution. Until the First World War, Glossop had the headquarters of the largest textile printworks in the world. In the 1920s, the firm was refloated on the easily available share capital; thus it was victim of the Stock Market Crash of 1929. Their product lines becoming vulnerable to the new economic conditions, and resulted in the industry's decline.[50]

Waterways

The streams of the Peak District have been dammed to provide headwater for numerous water driven mills; weirs have been built across the rivers for the same purpose.

There are no canals within the National Park boundary (though the Standedge Tunnels on the Huddersfield Narrow Canal run underneath the extreme north of the park). Waters from the Dark Peak fed the Ashton Canal, and Huddersfield Narrow Canal, and waters from the White Peak fed the Macclesfield Canal. Outside the National Park, but within the general area, the Peak Forest Canal was built to bring lime from the quarries at Dove Holes for the construction industry.

The canal terminated at Bugsworth and the journey was completed using the Peak Forest Tramway. Southeast of the National Park, the disused Cromford Canal ran from Cromford to the Erewash Canal and formerly served the lead mines at Wirksworth and cotton mills of Sir Richard Arkwright.

The large reservoirs along the Longdendale valley known as the Longdendale Chain were designed in the 1840s and completed in February 1877. They provided compensation water to ensure a continuous flow along the River Etherow which was essential for local industry, and provided pure water for Manchester.[19] The Upper Derwent Valley reservoirs were built from the mid 20th century onward to supply drinking water to the East Midlands and South Yorkshire.

Development of tourism

The area has been a tourist destination for centuries, with an early tourist description of the area, De Mirabilibus Pecci or The Seven Wonders of the Peak by Thomas Hobbes, being published in 1636.[51] Much scorn was poured on these seven wonders by subsequent visitors, including the journalist Daniel Defoe who described the moors by Chatsworth as "a waste and houling wilderness" and was particularly contemptuous of the cavern near Castleton known as the 'Devil's Arse' or Peak Cavern.[52] Visitor numbers did not increase significantly until the Victorian era, with railway construction providing ease of access and a growing cultural appreciation of the Picturesque and Romantic. Guides such as John Mawe's Mineralogy of Derbyshire (1802)[53] and William Adam's Gem of the Peak (1843)[54] generated interest in the area's unique geology.

Buxton has a long history as a spa town due to its geothermal spring which rises at a constant temperature of 28 °C. It was initially developed by the Romans around AD 78, when the settlement was known as Aquae Arnemetiae, or the spa of the goddess of the grove. It is known that Bess of Hardwick and her husband the Earl of Shrewsbury, "took the waters" at Buxton in 1569, and brought Mary, Queen of Scots, there in 1573.[55] The town largely grew in importance in the late 18th century when it was developed by the 5th Duke of Devonshire in style of the spa of Bath.

A second resurgence a century later attracted the eminent Victorians such as Dr. Erasmus Darwin and Josiah Wedgwood,[56] who were drawn by the reputed healing properties of the waters. The railway reached Buxton in 1863.[57] Buxton has many notable buildings such as 'The Crescent' (1780–1784), modelled on Bath's Royal Crescent, by John Carr, 'The Devonshire' (1780–1789), 'The Natural Baths', and 'The Pump Room' by Henry Currey. The Pavilion Gardens were opened in 1871.[55] Buxton Opera House was designed by Frank Matcham in 1903 and is the highest opera house in the country. Matcham was the theatrical architect who designed the London Palladium, the London Coliseum, and the Hackney Empire.

There is a great tradition of public access and outdoor recreation in the area. The Peak District formed a natural hinterland and rural escape for the populations of industrial Manchester and Sheffield, and remains a valuable leisure resource in a largely post-industrial economy.

In a 2005 survey of visitors to the Peak District, 85% of respondents mentioned "scenery and landscape" as a reason for visiting.[58]

Modern history

The Kinder Trespass in 1932 was a landmark in the campaign for national parks and open access to moorland in Britain. At the time, such open moors were closed to all; they were strongly identified with the game-keeping interests of landed gentry who used them only 12 days a year.[59] The Peak District National Park became the United Kingdom's first national park on 17 April 1951. The first long-distance footpath in the United Kingdom was the Pennine Way, which opened in 1965 and starts at the Nags Head Inn, in Grindsbook Booth, part of Edale village.

The northern moors of Saddleworth and Wessenden, above Meltham, gained notoriety in the 1960s as the burial site of several children murdered by Ian Brady and Myra Hindley.

Transport

History

The first roads in the Peak were constructed by the Romans, although they may have followed existing tracks. The Roman network is thought to have linked the settlements and forts of Aquae Arnemetiae (Buxton), Chesterfield, Ardotalia (Glossop) and Navio (Brough and Shatton), and extended outwards to Danum (Doncaster), Mamucium (Manchester) and Derventio (Little Chester, near Derby).[60] Parts of the modern A515 and A53 roads south of Buxton are believed to run along Roman roads.

Packhorse routes criss-crossed the Peak in the Medieval era, and some paved causeways are believed to date from this period, such as the Long Causeway along Stanage Edge. However, no highways were marked on Christopher Saxton's map of Derbyshire, published in 1579.[61] Bridge-building improved the transport network. A surviving early example is the three-arched gritstone bridge over the River Derwent at Baslow, which dates from 1608 and has an adjacent toll-shelter.[62]

Although the introduction of turnpike roads (toll roads) from 1731[63] reduced journey times, the journey from Sheffield to Manchester in 1800 still took 16 hours, prompting Samuel Taylor Coleridge to remark that "a tortoise could outgallop us!"[64] From around 1815 onwards, turnpike roads both increased in length and improved in quality. An example is the Snake Pass, which now forms part of the A57, built under the direction of Thomas Telford in 1819–21; the name refers to the crest of the Duke of Devonshire.[64] The Cromford Canal opened in 1794, carrying coal, lead and iron ore to the Erewash Canal.

Within several years, the improved roads and the Cromford Canal both saw competition from new railways, with work on the first railway in the Peak commencing in 1825.[64] Although the Cromford and High Peak Railway (from the Cromford Canal at High Peak Junction to Whaley Bridge) was an industrial railway, passenger services soon followed, including the Woodhead Line (Sheffield to Manchester via Longdendale) and the Manchester, Buxton, Matlock and Midlands Junction Railway. Not everyone regarded the railways as an improvement:

You enterprised a railroad through the valley, you blasted its rocks away, heaped thousands of tons of shale into its lovely stream. The valley is gone, and the gods with it; and now, every fool in Buxton can be at Bakewell in half-an-hour, and every fool in Bakewell at Buxton.

By the second half of the 20th century, the pendulum had swung back towards road transport. The Cromford Canal[65] was largely abandoned in 1944, and several of the rail lines passing through the Peak were closed as uneconomic in the 1960s as part of the Beeching Axe. The Woodhead Line was closed between Hadfield and Penistone. Parts of the trackbed are now used for the Trans Pennine Trail, the stretch between Hadfield and Woodhead being known specifically as the Longdendale Trail.[66]

The Manchester, Buxton, Matlock and Midlands Junction Railway is now closed between Rowsley and Buxton where the trackbed forms part of the Monsal Trail.[67] The Cromford and High Peak Railway is now completely shut, with part of the trackbed open to the public as the High Peak Trail.[68] Another disused rail line between Buxton and Ashbourne now forms the Tissington Trail.[69]

Road network

The main roads through the Peak District are the A57 (Snake Pass) between Sheffield and Manchester, the A628 (Woodhead Pass) between Barnsley and Manchester via Longdendale, the A6 from Derby to Manchester via Buxton, the Cat and Fiddle road from Macclesfield to Buxton, and in the extreme north of the Park the A635 (Saddleworth Moor) running from Manchester to Barnsley and the A62 from Manchester to Leeds, which forms the northernmost border of the National Park at Standedge. These major roads, together with other minor roads and lanes in the area, are attractive to drivers, but the Peak's popularity makes road congestion and the availability of parking spaces a significant problem, especially during summer. This led to the proposal of a congestion charge in 2005, but this was later rejected.[70]

Public transport

The Peak District is readily accessible by public transport, which reaches even central areas. Train services into the area are along the Hope Valley Line from Sheffield and Manchester, the Derwent Valley Line from Derby to Matlock, the Huddersfield Line from Manchester to Huddersfield, the Buxton Line and Glossop Line, linking those towns to Manchester. Coach (long-distance bus) services provide access to Matlock, Bakewell and Buxton from Derby, Nottingham and Manchester through TransPeak and National Express, and there are regular buses from the nearby towns of Sheffield, Glossop, Stoke, Leek and Chesterfield. The nearest airport is Manchester.[71]

For such a rural area, the smaller villages of the Peak are relatively well served by internal transport links. There are many minibuses operating from the main towns (Bakewell, Matlock, Hathersage, Castleton, Tideswell and Ashbourne) out to the small villages. The Hope Valley and Buxton Line trains also serve many local stations (including Hathersage, Hope and Edale).[72]

The National Park Authority announced, in October 2009, that Cycle England will be investing £1.25 million, to be spent by 2011, to build and improve cycle routes within the National Park for use by leisure and commuting cyclists.[73] It is hoped that this investment will help reduce traffic congestion and environmental pollution, as well as giving commuters and visitors a viable alternative to travelling around the National Park by car.

Activities

The Peak District provides opportunities for many types of outdoor activity. An extensive network of public footpaths and numerous long-distance trails, over 1,800 miles (2,900 km) in total,[74] as well as large open-access areas, are available for hillwalking and hiking. The Pennine Way traverses the Dark Peak from Edale to the Park's northern boundary just south of Standedge. Bridleways are commonly used by mountain bikers, as well as horse riders. Some of the long-distance trails in the White Peak, such as the Tissington Trail and High Peak Trail, re-use former railway lines; they are well used by walkers, horse riders and cyclists.[69]

The local authorities run cycle hire centres at Ashbourne, Parsley Hay, Middleton Top and the Upper Derwent Valley.[75][76] Wheelchair access is possible at several places on the former railway trails, and cycle hire centres offer vehicles adapted to wheelchair users.[69] There is a programme to make footpaths more accessible to less-agile walkers by replacing climbing stiles with walkers' gates.[77]

The many gritstone outcrops, such as Stanage Edge and The Roaches, are recognised as some of the finest rock climbing sites in the world[78] (see rock climbing in the Peak District); they were the first to be climbed. The Peak District's limestone was then 'discovered' by climbers.[79] It is more unstable but provides many testing climbs. For example, Thor's Cave was explored in the early 1950s by Joe Brown and others. Eleven limestone routes there are listed by the BMC, ranging in grade from Very Severe to E7, and several more have been claimed since the guidebook's publication; a few routes are bolted.[80]

Beneath the ground, the potholer enjoys natural caves, the potholes and old mine workings found in the limestone of the Peak. Peak Cavern is the largest and most important cave system which is even linked to the Speedwell system at Winnats. The only significant potholes are Eldon Hole and Nettle Pot. There are many old mine workings, which often were extensions of natural cave systems. Systems can be found at Castleton, Winnats, Matlock, Stoney Middleton, Eyam, Monyash and Buxton.[81]

Some of the area's large reservoirs, for example Carsington Water, have become centres for water sports, including sailing, fishing and canoeing, in this most landlocked part of the UK. Other activities include air sports such as hang gliding and paragliding, birdwatching, fell running, off-roading, and orienteering.[78]

Visitor attractions

Towns and villages

Buxton, Matlock and Matlock Bath, Bakewell, Leek and the small towns of Ashbourne and Wirksworth, on the fringes of the Park, all offer a range of tourist amenities. To the north the village of Hayfield sits at the foot of Kinder Scout, the highest summit in the area.

Bakewell is the largest settlement within the National Park; its five-arched bridge over the River Wye dates from the 13th century.[82]

The spa town of Buxton was developed by the Dukes of Devonshire as a genteel health resort in the 18th century. Although just outside the national park boundary, it is a popular attraction in the area. It has an opera house with a theatre, museum and art gallery.[83] Another spa town is Matlock Bath, popularised in the Victorian era.

The picturesque village of Castleton, overshadowed by Peveril Castle, has four show caves, the Peak, Blue John, Treak Cliff, and Speedwell, and is the centre of production of the unique semi-precious mineral, Blue John.[84] Other show caves and mines include the Heights of Abraham, reached by cable car, at Matlock Bath, and Poole's Cavern in Buxton. The small village of Eyam is known for its self-imposed quarantine during the Black Death of 1665.[85]

Historic buildings

Historic buildings include Chatsworth House, seat of the Dukes of Devonshire and among Britain's finest stately homes; the medieval Haddon Hall, seat of the Dukes of Rutland; Hardwick Hall, built by powerful Elizabethan Bess of Hardwick; and Lyme Park, an Elizabethan manor house transformed by an Italianate front.

Many of the Peak's villages and towns have fine parish churches, with a particularly magnificent example being the 14th century Church of St John the Baptist at Tideswell, sometimes dubbed the 'Cathedral of the Peak'. 'Little John's Grave' can be seen in the Hathersage churchyard. Historic castles include Bolsover Castle and Peveril Castle, both associated with the Normans.[86]

Museums and attractions

The Mining Museum at Matlock Bath, which includes tours of the Temple Lead Mine, and the Derwent Valley Mills World Heritage Site and Brindley Water Mill at Leek give insight into the Peak's industrial heritage. The preserved steam railway between Matlock and Rowsley, the National Tramway Museum at Crich and the Cromford Canal chart the area's transport history. The Life in a Lens Museum of Photography & Old Times in Matlock Bath presents the history of photography from 1839. Other attractions on the fringes of the national park include the theme parks of Alton Towers and Gulliver's Kingdom,[86] and the Peak Wildlife Park.

Local customs and events

Well dressing ceremonies are held in most of the villages during the spring and summer months, in a tradition said to date from pagan times.[87] Other local customs include Castleton's annual Garland Festival and Ashbourne's Royal Shrovetide Football, played annually since the 12th century. Buxton hosts two opera festivals, the Buxton Festival and the International Gilbert and Sullivan Festival, as well as the Buxton Festival Fringe, and the Peak Literary Festival is held at various locations twice a year.

Local cuisine

Peak District food specialities include the dessert Bakewell pudding, very different from the nationally available Bakewell tart, and until 2009 the famous cheese Stilton and other local cheeses were produced in the village of Hartington.

Conservation issues

The proximity of the Peak to major conurbations (an estimated 20 million people live within an hour's drive)[88] poses unique challenges to managing the area. The Peak District National Park Authority and the National Trust, with other landowners, attempt to balance keeping the upland landscape accessible to visitors for recreation, whilst protecting it from intensive farming, erosion and pressure from visitors themselves. An inevitable tension exists between the needs of the 38,000 residents of the Peak District National Park,[31] the many millions of people who visit it annually,[89] and the conservation requirements of the area.

The uneven distribution of visitors creates further stresses. Dovedale alone receives an estimated two million visitors annually;[10] other highly visited areas include Bakewell, Castleton and the Hope Valley, Chatsworth, Hartington and the reservoirs of the Upper Derwent Valley.[90] Over 60% of visits are concentrated in the period May–September, with Sunday being the busiest day.[90]

Footpath erosion

The number of footpath users on the more popular walking areas in the Peak District has contributed to serious erosion problems, particularly on the fragile peat moorlands of the Dark Peak. The recent use of some paths by mountain bikers is believed by some to have exacerbated an existing problem.[91] Measures taken to contain the damage have included the permanent diversion of the official route of the Pennine Way out of Edale, which now goes up Jacob's Ladder rather than following the Grindsbrook, and the surfacing of many moorland footpaths with expensive natural stone paving.[92]

Quarrying

Large-scale limestone quarrying has been a particular area of contention. Most of the mineral extraction licences were issued by national government for 90 years in the 1950s, and remain legally binding. The Peak District National Park Authority has a policy of considering all new quarrying and licence renewal applications within the area of the National Park in terms of the local and national need for the mineral and the uniqueness of the source, in conjunction with the effects on traffic, local residents and the environment.[32]

Some licences have not been renewed; for example, the RMC Aggregates quarry at Eldon Hill was forced to close in 1999, and landscaping is ongoing.[93] The proposals dating from 1999 from Stancliffe Stone Ltd to re-open dormant gritstone quarries at Stanton Moor have been seen as a test case. They are hotly contested by ecological protesters and local residents on grounds that the development would threaten nearby Bronze Age remains, in particular the Nine Ladies Stone Circle, as well as the natural landscape locally.[89] As of 2007, negotiations are ongoing to shift the development to the nearby Dale View quarry, a less sensitive area.[94]

Peak District in literature and arts

The landscapes of the Peak have formed an inspiration to writers for centuries. Various places in the Peak District have been identified by Ralph Elliott and others as locations in the 14th-century poem Sir Gawain and the Green Knight; Lud's Church for example, is thought to be the Green Chapel.[95]

Key scenes in Jane Austen's 1813 novel Pride and Prejudice are set in the Derbyshire Peak District.[96] Peveril of the Peak (1823) by Sir Walter Scott is a historical novel set at Peveril Castle, Castleton during the reign of Charles II.[97][98] William Wordsworth was a frequent visitor to Matlock; the Peak inspired several of his poems, including an 1830 sonnet to Chatsworth House.[99] The village of Morton in Charlotte Brontë's 1847 novel Jane Eyre is based on Hathersage, where Brontë stayed in 1845, and Thornfield Hall might have been inspired by nearby North Lees Hall.[100][101] Snowfield in George Eliot's first novel Adam Bede (1859) is believed to be based on Wirksworth, where her uncle managed a mill; Ellastone (as Hayslope) and Ashbourne (as Oakbourne) are also featured.[99]

Beatrix Potter, the author of Peter Rabbit, used to visit her uncle Edmund Potter at his printworks in Dinting Vale. She used cloth patterns from his Pattern Sample book to dress her characters. Mrs Tiggywinkle's shawl, in The Tale of Mrs. Tiggy-Winkle, is based on pattern number 222714.[102]

Children's author Alison Uttley (1884–1976) was born at Cromford; her well-known novel A Traveller in Time, set in Dethick, recounts the Babington Plot to free Mary, Queen of Scots, from imprisonment.[103] Crichton Porteous (1901–91) set several books in specific locations in the Peak; Toad Hole, Lucky Columbell and Broken River, for example, are set in the Derwent Valley.[104] More recently, Geraldine Brooks's first novel, Year of Wonders (2001), blends fact and fiction to tell the story of the plague village of Eyam,[105] which also inspired Children of Winter by children's novelist Berlie Doherty (b. 1943). Doherty has set several other works in the Peak, including Deep Secret, based on the drowning of the villages of Derwent and Ashopton by the Ladybower Reservoir, and Blue John, inspired by the Blue John Cavern at Castleton.[106]

Many works of crime and horror have been set in the Peak. The Terror of Blue John Gap by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859–1930) recounts terrible events at the Blue John mines,[107] and Sherlock Holmes investigates the kidnapping of a child in the region in The Adventure of the Priory School.[108] Many of the horror stories of local author Robert Murray Gilchrist (1878–1916) feature Peak settings.[99] More recently, Stephen Booth has written a series of crime novels set in various real and imagined Peak locations,[109] while In Pursuit of the Proper Sinner, an Inspector Lynley mystery by Elizabeth George, is set on the fictional Calder Moor.[110]

Other writers and poets who lived in or visited the Peak include Samuel Johnson, William Congreve, Anna Seward, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Lord Byron, Thomas Moore, Richard Furness, D. H. Lawrence, Vera Brittain, Richmal Crompton and Nat Gould.[99][103] The landscapes and historic houses of the Peak are also popular settings for film and television. The classic 1955 film The Dam Busters was filmed at the Upper Derwent Valley reservoirs, where practice flights for the bombing raids on the Ruhr dams had been made during the Second World War.[111]

In recent adaptations of Pride and Prejudice, Longnor has featured as Lambton, while Lyme Park and Chatsworth House have stood in for Pemberley.[112][113] Haddon Hall not only doubled as Thornfield Hall in two different adaptations of Jane Eyre, but has also appeared in several other films including Elizabeth, The Princess Bride and The Other Boleyn Girl.[114] The long-running television medical drama Peak Practice is set in the fictional village of Cardale in the Derbyshire Peak District; it was filmed in Crich, Matlock and other Peak locations.[115]

See also

- List of hills in the Peak District

- Forest of High Peak a royal hunting reserve in medieval times in the area

- Derbyshire moors

References

- ↑ Peak District Local Government (Retrieved 8 November 2016)

- ↑ "Quarrying and mineral extraction in the Peak District National Park" (PDF). Peak District National Park Authority. 2011. Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- ↑ Wheeler, T. (2003). Else, D, ed. Britain (5th ed.). Lonely Planet. p. 42. ISBN 1-74059-338-3.

The Peak District alone gets 20 million, making it Britain's most-visited park, and the second-busiest in the world.

- ↑ "Media Centre Facts and Figures". Peak District National Park Authority. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- ↑ Nuttall, J.; Nuttall, A. (1990). The Mountains of England & Wales – Volume 2: England. Milnthorpe: Cicerone. ISBN 1-85284-037-4. Retrieved 23 August 2009.

- ↑ "The Peak District National Park – Fact Zone". PDNP Education. 2000. Retrieved 22 May 2009.

- ↑ "National Park facts and figures". National Parks. 2009. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012. Retrieved 13 November 2013.

- ↑ Handbook for Members and Visitors 2004, The National Trust.

- ↑ "High Peak Estate". The National Trust. 2009. Archived from the original on 26 April 2009. Retrieved 22 May 2009.

- 1 2 "Ilam Park and South Peak Estate". The National Trust. 2010. Archived from the original on 15 July 2010. Retrieved 26 September 2010.

- ↑ "Longshaw Estate". The National Trust. 2009. Retrieved 22 May 2009.

- 1 2 "Peak District National Park Authority factsheets". Peak District National Park Authority. 2012. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- ↑ Gannon, Paul, Rock Trails Peak District:A Hillwalker's Guide to the Geology and Scenery, Pesda Press, 2011, ISBN 978-1-906095-24-6

- 1 2 Cope, F. W. (1976). Geology Explained in the Peak District. David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-6945-8.

- 1 2 3 "The Peak District is a very interesting area geologically". Peak District Information. Cressbrook Multimedia. 2008. Retrieved 24 May 2009.

- ↑ Aitkenhead, N. et al. 2002 British Regional Geology: the Pennines and adjacent areas (4th Edn) (BGS, Nottingham)

- ↑ Macdougall, D. (2006). The Geology of Britain. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-24824-4.

- ↑ Toghill, P. (2002). The Geology of Britain. Crowood Press. ISBN 1-84037-404-7.

- 1 2 Quayle, Tom (2006). Manchester's Water: The Reservoirs in the Hills. Stroud: Tempus Publishing. p. 15. ISBN 0-7524-3198-6.

- ↑ Bevan, Bill (2004). The Upper Derwent: 10,000 Years in a Peak District Valley. Stroud: Tempus Publishing. pp. 141–159. ISBN 0-7524-2903-5.

- ↑ "River Derwent". Peak District Online. 2009. Retrieved 1 July 2009.

- ↑ "The Manifold is a sister river to the Dove". Peak District Information. Cressbrook Multimedia. 2008. Retrieved 1 July 2009.

- ↑ "The Dove is the major river of the South Peak". Peak District Information. Cressbrook Multimedia. 2008. Retrieved 1 July 2009.

- ↑ "The Dane flows west into Cheshire". Peak District Information. Cressbrook Multimedia. 2008. Retrieved 1 July 2009.

- ↑ "Peak District National park: Place". Peak District National Park. 2003. Retrieved 22 May 2009.

- 1 2 "Biodiversity Action Plan – The Lead Legacy". Peak District. 2004. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 13 November 2013.

- ↑ "Kinder Scout – the highest gritstone peak in the Peak District". Peak District Information. 2008. Retrieved 21 May 2009.

- ↑ "Peak District Climate". Peak District National Park. 2003. Archived from the original on 24 July 2008. Retrieved 13 November 2013.

- ↑ "About the Peak District ...". ThePeakDistrict.info. 2007. Retrieved 23 May 2009.

- ↑ "Moorland Indicators of Climate Change Initiative 2012". Peak District. 2012. Archived from the original on 22 January 2012. Retrieved 3 April 2012.

- 1 2 "A place called home". Peak District. 2009. Archived from the original on 19 May 2009. Retrieved 22 May 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 "Peak District National Park: Study Area". Peak District National Park. 2003. Archived from the original on 2 May 2009. Retrieved 22 May 2009.

- 1 2 Waugh, D. (2000). Geography An Integrated Approach (3rd ed.). Nelson Thornes. ISBN 0-17-444706-X.

- ↑ "Margery Hill, South Yorkshire". English Heritage. 1994. Archived from the original on 12 October 2008. Retrieved 22 May 2009.

- ↑ Bevan, Bill (2007). Ancient Peakland. Wellington: Halsgrove. ISBN 1-84114-593-9.

- ↑ "Aquae Arnemetiae". RomanBritain.org. 2005. Retrieved 22 May 2009.

- ↑ "Peak District history : Anglo Saxons to Present". Peakscan. Retrieved 28 June 2009.

- ↑ Turbutt, G. (1999). A History of Derbyshire, Volume 1. Cardiff: Merton Priory. ISBN 1-898937-34-6.

- ↑ Ford, T. D. (2002). Rocks and Scenery of the Peak District. Landmark Publishing. ISBN 1-84306-026-4.

- ↑ Fiennes, C. (1888). Through England on a Side Saddle in the Time of William and Mary. London: Field and Tuer, The Leadenhall Press. Retrieved 22 May 2009.

- ↑ "Goyt's Moss and Axe Edge Moor Update" (PDF). Environment News 12. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 July 2004. Retrieved 13 November 2013.

- ↑ "Peak District Coal Mining". Peak District National Park. 2003. Archived from the original on 9 August 2010. Retrieved 13 November 2013.

- 1 2 "Mining in the Peak District of Derbyshire Lead and Copper Minerals". A Taste of the Peak District. Retrieved 24 June 2009.

- ↑ "Blue John Stone". BlueJohnStone.co.uk. 2007. Retrieved 30 June 2009.

- ↑ "The Buxton Story". Tarmac. 2006. Retrieved 1 July 2009.

- ↑ "Peak District industry". British Geological Survey. Retrieved 22 May 2009.

- ↑ "Textiles". Peakland Heritage. Retrieved 23 May 2009.

- ↑ Williams, M. (1992). Cotton Mills of Greater Manchester. Carnegie Publishing. p. 49. ISBN 0-948789-89-1.

- ↑ "Children of the Revolution". Cotton Times. Retrieved 31 March 2009.

- ↑ Birch, A. H. (1959). "2". Small-Town Politics: A Study of Political Life in Glossop. Oxford University Press. pp. 8–38. ISBN 0-273-70161-4.

- ↑ "1678 – De Mirabilibus Pecci – Being the Wonders of the Peak in Darby-shire". British Library. Retrieved 22 May 2009.

- ↑ Defoe, D. (1927). A tour thro' the whole island of Great Britain, divided into circuits or journies. London: J. M. Dent. Retrieved 22 May 2009.

- ↑ Mawe, J. (1802). The Mineralogy of Derbyshire. London: William Phillips. Retrieved 22 May 2009.

- ↑ Adam, W. (1843). Gem of the Peak or Matlock Bath and its vicinity. London: Longman. Retrieved 22 May 2009.

- 1 2 "Things to do in Buxton" (PDF). Quantifying and Understanding the Earth System. Retrieved 28 June 2009.

- ↑ Darwin, C. (1985). The correspondence of Charles Darwin. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 28 June 2009.

- ↑ Blakemore, B.; Mosley, D. (2003). Railways of the Peak District. Great Northern Books. ISBN 1-902827-09-0.

- ↑ "Landscape Character" Peak District National Park, retrieved 20 August 2015

- ↑ Renton, D. (23 February 2007). "Kinder Trespass: Context in 1932". The Kinder Trespass 75 organising committee. Archived from the original on 21 February 2009. Retrieved 28 June 2009.

- ↑ "The Romano-British Settlements". RomanBritain.org. 10 September 2010. Retrieved 26 September 2010.

- ↑ "Peak District Routes, Stoops, Pack Horse Ways, Turnpikes". Peakscan. 2008. Retrieved 22 May 2009.

- ↑ "Baslow Bridge, Bubnell Lane". Images of England. 2000. Retrieved 22 May 2009.

- ↑ "Longendale in the Peak National Park". PDNP Education. 2000. Archived from the original on 4 January 2006. Retrieved 22 May 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 Stainforth, G. (1998). The Peak: Past and Present. Constable. ISBN 0-09-475420-9.

- ↑ "Cromford Canal". Discover Derbyshire and the Peak District. Retrieved 1 July 2009.

- ↑ "Glossop/Longdendale Walk". Discover Derbyshire and the Peak District. Retrieved 1 July 2009.

- ↑ "Monsal Trail". Discover Derbyshire and the Peak District. Retrieved 1 July 2009.

- ↑ "The High Peak Trail". Discover Derbyshire and the Peak District. Retrieved 1 July 2009.

- 1 2 3 "Tissington Trail". Discover Derbyshire and the Peak District. Retrieved 1 July 2009.

- ↑ Giannangeli, M. (5 December 2005). "Peak District may be first national park to impose a congestion charge". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 23 May 2009.

- ↑ "Public Transport – Peak District National Park Authority". Peak District. 2012. Retrieved 3 April 2012.

- ↑ "Public Transport in Derbyshire and the Peak District". Discover Derbyshire and the Peak District. 2009. Retrieved 22 June 2009.

- ↑ "Pedal power to help residents and visitors lead more active lifestyles – Peak District National Park Authority". Peak District. 7 October 2009. Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 16 October 2009.

- ↑ "Peak District National Park: Study Area". Peak District National Park. Archived from the original on 22 October 2008. Retrieved 22 June 2009.

- ↑ "Cycle hire". Derbyshire County Council. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- ↑ "Cycling". Peak District National Park. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- ↑ "Local Activities in & around the Peak District National Park". Roaches Holiday Cottages. Retrieved 22 June 2009.

- 1 2 "Peak District". Trekking World. Retrieved 22 June 2009.

- ↑ "Peak District Rock climbing". Peak District Information. Cressbrook Multimedia. 2008. Retrieved 30 June 2009.

- ↑ Milburn, G. (1987). Rock Climbs in the Peak District: Peak Limestone: South. British Mountaineering Council. ISBN 0-903908-26-3.

- ↑ "Pot holing". Peak District Information. Cressbrook Multimedia. 2008. Retrieved 30 June 2009.

- ↑ "Bakewell". Places-to-go.org.uk. 2003. Retrieved 18 June 2009.

- ↑ "Visit Buxton". VisitBuxton.co.uk. 2007. Retrieved 18 June 2009.

- ↑ "The World Famous Blue John Cavern And Original Blue John Craft Shop". The Blue John Cavern. Retrieved 18 June 2009.

- ↑ "Mystery of the Black Death". Secrets of the Dead. Retrieved 18 June 2009.

- 1 2 "Peak District Attractions". Peak District Online. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- ↑ "More about Well Dressings". WellDressing.com. Retrieved 18 June 2009.

- ↑ "Peak District National Park". ByGoneDerbyshire.co.uk. 28 January 2010. Retrieved 26 September 2010.

- 1 2 Moss, C. (28 February 2004). "Oops, there goes another bit of Britain". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 May 2009.

- 1 2 "Tourism in the Peak District National Park". Peak District National Park. 2003. Archived from the original on 22 October 2008. Retrieved 22 May 2009.

- ↑ "Peak District National Park: Study Area – Footpath Erosion". Peak District National Park. Archived from the original on 27 May 2009. Retrieved 22 June 2009.

- ↑ "Peak District National Park: Study Area – The Pennine Way". Peak District National Park. Archived from the original on 27 May 2009. Retrieved 22 June 2009.

- ↑ "Peak District Biodiversity Action Plan" (PDF). Peak District. October 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 13 November 2013.

- ↑ "End in sight for quarry wrangle on historic moor". Peak District. 5 September 2007. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 12 September 2007.

- ↑ Elliott, R. W. V.; Brewer, Derek; Gibson, J. (1999). "Landscape and Geography". A Companion to the Gawain-Poet. Brewer D. S. pp. 105–117. ISBN 0-85991-529-8.

- ↑ "Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen". Project Gutenberg. 2003. Retrieved 13 September 2007.

- ↑ "Peveril Castle". English Heritage Archive. 2007. Retrieved 12 September 2007.

- ↑ Ousby, I. (1993). Ousby I, ed. The Cambridge Guide to Literature in English (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 734. ISBN 0-521-44086-6.

- 1 2 3 4 "Peak Film & Literature". Peak Experience. Retrieved 12 September 2007.

- ↑ Brontë, C. (1996). Jane Eyre. Penguin Books. p. 526. ISBN 0-14-043400-3.

- ↑ Barker, J. (1995). The Brontës. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. pp. 451–453. ISBN 1-85799-069-2.

- ↑ Potter, E. (1892). "Dinting Vale Printworks cotton sample pattern book". Spinning the Web. Manchester City Council. Retrieved 28 June 2009.

- 1 2 "Peakland Writers". Peakland Heritage. 2008. Retrieved 12 September 2007.

- ↑ "Crichton Porteous – Derbyshire Writer". About Derbyshire. 3 June 2007. Retrieved 12 September 2007.

- ↑ "Year of Wonders". GeraldineBrooks.com. 2007. Retrieved 13 November 2013.

- ↑ "Berlie Doherty: novels". BerlieDoherty.com. 2003. Archived from the original on 2 August 2007. Retrieved 12 September 2007.

- ↑ "Tales of Terror and Mystery by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle". Gutenberg. 2008. Retrieved 13 September 2007.

- ↑ "The Adventure of the Priory School". Camden House – The Complete Sherlock Holmes. 1998. Retrieved 13 September 2007.

- ↑ "Stephen Booth – New Books". StephenBooth.com. Retrieved 12 September 2007.

- ↑ "Novel – In Pursuit of the Proper Sinner". Elizabeth George Online. Retrieved 12 September 2007.

- ↑ "Filming locations for The Dam Busters". Internet Movie Database. 1990. Retrieved 13 September 2007.

- ↑ "Filming locations for Pride and Prejudice (1995)". Internet Movie Database. 1995. Retrieved 12 September 2007.

- ↑ "Filming locations for Pride and Prejudice (2005)". Internet Movie Database. 2005. Retrieved 12 September 2007.

- ↑ "Film & Photoshoots". Haddon Hall. Retrieved 22 June 2009.

- ↑ "Filming locations for Peak Practice". Internet Movie Database. 1993. Retrieved 12 September 2007.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Peak District. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Peak District. |

- Official website of the Peak District National Park Authority ()

- Peak District at The National Trust

- Foundations of the Peak – geological information at British Geological Survey

- Visit Peak District & Derbyshire official Tourist information