Peace of Szeged

The Treaty of Edirne and the Peace of Szeged were two halves of a peace treaty between Sultan Murad II of the Ottoman Empire and King Vladislaus of the Kingdom of Hungary. Despot Đurađ Branković of the Serbian Despotate also had a large role in the proceedings. The ratification took place on August 15, 1444 in Várad, a few months before the end of the Crusade of Varna.

The treaty was started in Edirne with discussions between Murad and Vladislaus' ambassador. Within a few days, it was sent to Szeged with Murad's ambassador, to be finalized and ratified by Vladislaus. Once it arrived, complications caused the negotiations to continue for several more days, and oaths were eventually given in Várad.

Background

The Crusade of Varna officially began on January 1, 1443, with a crusading bull published by Pope Eugene IV. The fighting did not start as planned, however. The Hungarian and Karamanid armies were supposed to attack the Ottoman Empire simultaneously, but in the spring of 1443, before the Hungarians were ready, the Karamanids attacked the Ottomans and were devastated by Sultan Murad II's full army.[1]

The Hungarian army, led by King Vladislaus, John Hunyadi, and Serbian Despot Đurađ Branković, attacked in mid-October. They had several advantages over the Ottomans, allowing them to win the first encounters, such as forcing Kasim Pasha of Rumelia and his co-commander Turakhan Beg to abandon camp and flee to Sofia, Bulgaria to warn Murad of the invasion. However, the two burned all the villages in their path to wear down the Hungarians with scorched earth. When they arrived in Sofia, they advised the Sultan to burn the city and retreat to the mountain passes beyond, where the Ottoman's smaller army wouldn't be such a disadvantage. Shortly after, bitter cold set in.[1]

The next encounter, fought at Zlatitsa Pass just before Christmas 1443, was fought in the snow. The Hungarians were badly defeated. As they marched home, however, they ambushed and defeated a pursuing force in the Battle of Kunovica, where Mahmud Bey, son-in-law of the Sultan and brother of the Grand Vizier Çandarlı Halil Pasha, was taken prisoner. This returned to the Hungarians the illusion of an overall Christian victory, and they returned triumphant. The King and Church were both anxious to maintain the illusion and gave instructions to spread word of the victories, but contradict anyone who mentioned the loss.[1]

Murad, meanwhile, returned angry and dejected by the unreliability of his forces, and imprisoned Turakhan after blaming him for the army's setbacks and Mahmud Bey's capture.[1]

Thoughts of peace

Murad is believed to have had the greatest wish for peace. Among other things, his sister begged him to obtain her husband Mahmud's release, and his wife Mara, daughter of Đurađ Branković, added additional pressure. On March 6, 1444, Mara sent an envoy to Branković; their discussion started the peace negotiations with the Ottoman Empire.[1]

On April 24, 1444, Vladislaus sent a letter to Murad, stating that his ambassador, Stojka Gisdanić, was travelling to Edirne with full powers to negotiate on his behalf. He asked that, once an agreement was reached, Murad send his own ambassadors with the treaty and his sworn oath to Hungary, at which point Vladislaus could also swear.[1]

That same day, Vladislaus held a Diet at Buda, where he swore before Cardinal Julian Cesarini to lead a new expedition against the Ottomans in the summer. The strongest remaining supporter of Ladislaus' claim for the throne also agreed to a truce, thus removing the danger of another civil war.[1]

Edirne

Early negotiations resulted in the release of Mahmud Bey, who arrived in Edirne around early June 1444. Vladislaus' ambassador Stojka Gisdanić arrived soon after, along with, as required by a law signed by King Albert, Hunyadi's representative Vitislav, and two representatives for Branković. At the behest of Pope Eugene IV, the antiquarian Ciriaco Pizzicolli was also present to monitor the progress of crusade plans.[1]

During the negotiations, the most contentious point was the possession of Danubian fortresses, especially Golubac and Smederevo, which the Ottomans wished to retain. However, on June 12, 1444, after three days of discussion, the treaty was hastily completed because Ibrahim of Karaman had invaded Murad's lands in Anatolia.[1]

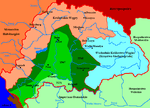

The final terms stated that Murad would return 24 Serbian cities, including the large fortresses of Golubac and Smederevo, to the exiled Branković. Murad was also obliged release Branković's two blinded sons, Grgur and Stefan. The restored Serbian Despotate was vassalaged to the Ottomans, however, so had to pay taxes and offer military aid. A ten-year truce was established with Hungary, and Vlad II Dracul, Voivode of Wallachia, was no longer obliged to attend Murad's court, though he was still required to pay tribute.[1]

Once Murad had sworn an oath to observe the treaty, it was sent to Hungary with Baltaoğlu Süleyman and a Greek, Vranas, for ratification by Vladislaus, Hunyadi, and Branković.[1]

Intervening politicking

Despite the progressing treaty, planning for the crusade against the Ottomans continued. It is generally assumed that Vladislaus knew the results of the negotiations in Edirne by the beginning of July. Yet on July 2, 1444, at the urging of Cardinal Cesarini, Vladislaus reassured his allies of his intentions to lead the crusade by declaring he would head to Várad on July 15 to assemble an army. The reassurance was necessary because the strength of Vladislaus' resolve did not match that of his public statements. Though he was under significant pressure to carry out the expedition, he received equal pressure to abandon it entirely.[1]

A crusade would add legitimacy to Vladislaus' claim to the throne, and a Polish faction especially wanted verification of his right to rule over the infant Ladislaus. He also faced Cesarini, who fervently believed in the crusade, and had incredible powers of persuasion. By the time the King made his declaration, word of the peace negotiations had spread, prompting added pressure by pro-crusaders, including Despot Constantine Dragases, to renounce the treaty.[1]

Meanwhile, in Poland, there was civil strife, and a faction there demanded he return to end it. The losses during the war in the winter of 1443 likely also disinclined Vladislaus to start another war. Above all, the continuing peace negotiations were in direct opposition to war.[1]

Vladislaus was not the only one to be coerced. A letter written by Ciriaco Pizzicolli on June 24, 1444 begged Hunyadi to ignore the peace, stating the Turks were terrified "and preparing their army for retreat rather than battle." He continued to explain that the treaty would allow Murad "to avenge the defeat that [Hunyadi] inflicted on him in the recent past," and that Hungary and the other Christians should invade Thrace after "[declaring] a war worthy of the Christian religion."[1]

Branković, however, had a much larger interest in the peace treaty going through, and solicited Hunyadi's support. The expectation was that Serbia would be returned to Branković upon ratification of the treaty, and as such, he bribed Hunyadi by promising him the land and power he held in Hungary. On July 3, 1444, the lordship of Világosvár was transferred, in perpetuity, to Hunyadi. Around the same time, as additional security, the estates of Mukačevo, Baia Mare, Satu Mare, Debrecen, and Böszörmény were also transferred, and Hunyadi became the largest landowner in the Kingdom.[1]

Shortly after Vladislaus' declaration, around the same time as writing the letter to Hunyadi, Ciriaco passed the news to the Pope, who in turn informed Cesarini. Cesarini, meanwhile, had staked his career on the crusade, a result of supporting the Pope against the Council of Basel, which he had abandoned in the late 1430s. He was therefore left with the necessity of finding a solution between the two sides.[1]

Szeged

At the beginning of August, the Ottoman ambassadors Baltaoğlu and Vranas arrived in Szeged. On August 4, 1444, Cardinal Cesarini implemented the solution he had created for the King. With Hunyadi, the barons, and the prelates of the Kingdom of Hungary in attendance, Vladislaus was made to "abjure any treaties, present or future, which he had made or was to make with the Sultan." Cesarini had carefully worded the declaration such that negotiations could continue and the treaty could still be ratified by oath, without cancelling the possibility of a crusade or breaking the terms of the treaty because the oath was invalidated even before it was given.[1]

Despite Cesarini's solution, the negotiations lasted for ten days. The final version of the treaty re-established Serbia as a buffer state and settled its return to Branković,[2] as well as the return of Albania and all other territory conquered, including 24 fortresses, to Hungary. The Ottomans also had to pay an indemnity of 100,000 gold florins and release Branković's two sons.[3][4] Hungary, meanwhile, agreed to not attack Bulgaria or cross the Danube,[2] and a truce of 10 years was established. It is also suspected that Branković, who gained the most from the treaty, concluded his own private negotiations with Baltaoğlu, though the results are unknown.[1]

On August 12 and 14, Cesarini and De Reguardati sent instructions to the Venetian senate explaining what to do once the treaty was concluded. On August 15, 1444, the treaty was ratified in Várad with oaths by Hunyadi, for both himself and "on behalf of the King himself and all the people of Hungary", and Branković. Although Vladislaus did not swear to the treaty himself; the broken oath weighed on his conscience.[1]

Consequences

On August 22, 1444, a week after the negotiations were finalized, Branković retook Serbia. During that week, Vladislaus also offered the Kingship of Bulgaria to Hunyadi, if he was amenable to abjuring his oath, which he was. By mid-September, all transfers, both those decreed by the treaty and those by background negotiations, were completed, allowing the crusade to become Hungary's primary focus.[1]

The Ottoman Empire, meanwhile, had heard nothing about Cesarini's invalidation of the treaty, and by the end of August 1444, the Karamanids were also subdued, leaving Murad with the impression that his borders were secure. He further planned that the favorable terms granted in both the Peace of Szeged and the settlement with Ibrahim of Karaman would cause a lasting peace. Shortly after Ibrahim's submission, therefore, Murad abdicated in favor of Mehmed II, his twelve-year-old son, intending for his plans to allow a peaceful retirement.[1][2]

Murad's hope was not fulfilled, however. By late September, Hungary's preparations for the crusade were complete, and those of their allies were well underway. Many formerly independent Ottoman fringe territories began reclaiming their land, and on September 20, 1444, the Hungarian army began marching south from Szeged. The march went well for the Hungarians, prompting the Ottomans to recall Murad. On November 10, 1444, the two armies clashed, and the following Battle of Varna brought about Vladislaus' death and a disastrous end for the entire Hungarian side.[1][3][4]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 Imber, Colin (July 2006). "Introduction" (PDF). The Crusade of Varna, 1443–45 (PDF). Ashgate Publishing. pp. 9–31. ISBN 0-7546-0144-7. Retrieved 2007-04-19. Archived June 28, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 3 Sugar, Peter (1977). "Chapter 1: The Early History and the Establishment of the Ottomans in Europe". Southeastern Europe Under Ottoman Rule, 1354-1804 (Reprint). University of Washington Press. Retrieved 2007-05-19.

- 1 2 Perjes, Geza (1999) [1989]. "Chapter I: Methodology". In Bela Kiraly; Peter Pastor. The Fall of The Medieval Kingdom of Hungary: Mohacs 1526 - Buda 1541. Translated by Maria D. Fenyo. Columbia University Press / Corvinus Library - Hungarian History. ISBN 0-88033-152-6. LCCN 88062290. Retrieved 2007-03-23.

- 1 2 "Wladislaus III". Classic Encyclopedia (Reprint of Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition ed.). LoveToKnow 1911. 2006. Retrieved 2007-05-19.