Pastoral epistles

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Paul in the Bible |

|---|

.jpg) |

|

See also |

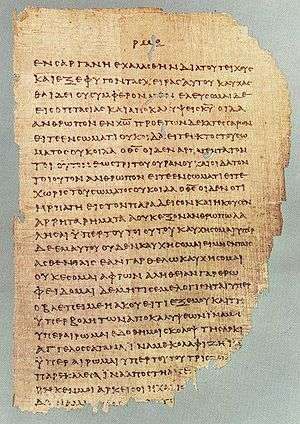

The pastoral epistles are three books of the canonical New Testament: the First Epistle to Timothy (1 Timothy) the Second Epistle to Timothy (2 Timothy), and the Epistle to Titus. They are presented as letters from Paul the Apostle to Timothy and to Titus. They are generally discussed as a group (sometimes with the addition of the Epistle to Philemon) and are given the title pastoral because they are addressed to individuals with pastoral oversight of churches and discuss issues of Christian living, doctrine and leadership. The term "pastorals" was popularized in 1703 by D. N. Berdot and in 1726 by Paul Anton.[1]

1 Timothy

1 Timothy consists mainly of counsels to Timothy regarding the forms of worship and organization of the church, and the responsibilities resting on its several members, including episkopoi (translated as "bishops") and diakonoi ("deacons"); and secondly of exhortation to faithfulness in maintaining the truth amid surrounding errors (iv.iff), presented as a prophecy of erring teachers to come. The epistle's "irregular character, abrupt connections and loose transitions" (EB 1911) have led critics to discern later interpolations, such as the epistle-concluding 6:20–21, read as a reference to Marcion of Sinope, and lines that appear to be marginal glosses that have been copied into the body of the text.

2 Timothy

The author (who identifies himself as Paul the Apostle) entreats Timothy to come to him before winter, and to bring Mark with him (cf. Phil. 2:22). He was anticipating that "the time of his departure was at hand" (4:6), and he exhorts his "son Timothy" to all diligence and steadfastness in the face of false teachings, with advice about combating them with reference to the teachings of the past, and to patience under persecution (1:6–15), and to a faithful discharge of all the duties of his office (4:1–5), with all the solemnity of one who was about to appear before the Judge of the living and the dead.

Titus

This short letter is addressed to Titus, a Christian worker in Crete, and is traditionally divided into three chapters. It includes advice on the character and conduct required of Church leaders (chapter 1), a structure and hierarchy for Christian teaching within the church (chapter 2), and the kind of godly conduct and moral action required of Christians in response to God's grace and gift of the Holy Spirit (chapter 3). It includes the line quoted by the author from a Cretan source: "Cretans are always liars, wicked beasts, and lazy gluttons" (Titus 1:12).

Authorship

The letters are written in Paul's name and have traditionally been accepted as authentic.[2] Since the 1700s, however, experts have increasingly come to see them as the work of someone writing after Paul's death.[2]

Traditional view: Saint Paul

Among the Apostolic Fathers, 'a strong case can be made for Ignatius' use of ... 1 and 2 Timothy'.[3] Similarly for Polycarp.[4] The unidentified author of the Muratorian fragment (c.170) lists the Pastorals as Pauline, while excluding others e.g. to the Laodiceans. Origen[5] refer to the "fourteen epistles of Paul" without specifically naming Titus or Timothy.[6] However it is believed that Origen wrote a commentary on at least the epistle to Titus.[7]

Biblical scholars such as Michael Licona or Ray Van Neste,[8] who ascribe the books to Paul find their placement fits within his life and work and see the linguistic differences as complementary to differences in the recipients. Other Pauline epistles have fledgling congregations as the audience, the pastoral epistles are directed to Paul's close companions, evangelists whom he has extensively worked with and trained. In this view, linguistic differences are to be expected, if one is to assert Pauline authorship to them. Johnson[9] asserts the impossibility of demonstrating the authenticity of the Pastoral Letters.

Critical view: rejecting Pauline authorship

On the basis of their language, content, and other factors, the pastoral epistles are today widely regarded as not having been written by Paul, but after his death.[10] (Although the Second Epistle to Timothy is sometimes thought to be more likely than the other two to have been written by Paul.) Beginning with Friedrich Schleiermacher in a letter published in 1807, biblical textual critics and scholars examining the texts fail to find their vocabulary and literary style similar to Paul's unquestionably authentic letters, fail to fit the life situation of Paul in the epistles into Paul's reconstructed biography, and identify principles of the emerged Christian church rather than those of the apostolic generation.[11]

As an example of qualitative style arguments, in the First Epistle to Timothy the task of preserving the tradition is entrusted to ordained presbyters; the clear sense of presbuteros as an indication of an office, is a sense that to these scholars seems alien to Paul and the apostolic generation. Examples of other offices include the twelve apostles in Acts and the appointment of seven deacons, thus establishing the office of the diaconate. Presbuteros is sometimes translated as elder; by a longer route it is also the Greek root for the English word priest. (The office of presbyter is also mentioned in James chapter 5.)[11]

A second example would be gender roles depicted in the letters, which proscribe roles for women that appear to deviate from Paul's more egalitarian teaching that in Christ there is neither male nor female.[11] Separate male and female roles, however, were not foreign to the authentic Pauline epistles; the First Letter to the Corinthians (14:34–35) commands silence from women during church services, stating that "it is a shame for women to speak in the church." Father Jerome Murphy-O'Connor, O.P., in the New Jerome Biblical Commentary,agrees with many other commentators on this passage over the last hundred years in recognising it to be an interpolation by a later editor of 1 Corinthians of a passage from 1 Timothy 2:11–15 that states a similar "women should be silent in churches". This made 1 Corinthians more widely acceptable to church leaders in later times. If verses before or after 1 Corinthians 14:34–35 are read, it is fairly clear that verses 34 and 35 were inserted later.[12]

Similarly, biblical scholars since Schleiermacher in 1807 have noted that the pastoral epistles seem to argue against a more developed Gnosticism than would be compatible with Paul's time.[11]

Scholars refer to the anonymous author as "the Pastor".[2]

Date

It is "highly probable that 1 and 2 Timothy were known and used by Polycarp".[13] Irenaeus made extensive use of the two epistles to Timothy as the prime force of his anti-gnostic campaign, ca. 170 AD. Proposals by scholars for the date of their composition have ranged from the 1st century to well into the second.

The later dates are usually based on the hypothesis that the Pastorals are responding to specific 2nd-century developments (Marcionism, gnosticism). That Marcion (ca. 140) betrays knowledge of a collection of Paul's letters that lack the Pastoral Epistles is another piece of evidence for which any model must account.[14] (This is a separate question to Marcion's "canon", which included only edited versions of Luke and the Pauline epistles; according to Tertullian, Marcion "omitted" the Epistle to the Hebrews and the Pastoral Epistles.)

According to Raymond E. Brown (An Introduction to the New Testament, 1997), the majority of scholars who accept a post-Pauline date of composition for the Pastorals favour the period 80–100. Scholars supporting a date in this mid range can draw on the description in 2 Timothy 1:5 of Timothy's Christian mother and grandmother who passed on their faith, as alluding to the original audience being third generation Christians.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Donald Guthrie, (2009), "The Pastoral Epistles," Inter-Varsity Press, ISBN 978-0-8308-4244-5, p. 19

- 1 2 3 Harris, Stephen L., Understanding the Bible. Palo Alto: Mayfield. 1985. “The Pastoral Epistles“ p. 340–345

- ↑ Paul Foster, "Ignatius of Antioch," in Gregory and Tuckett (eds), (2005), The Reception of the NT in the Apostolic Fathers, OUP, p.185

- ↑ Michael W. Holmes, in Gregory and Tuckett (eds), (2005), The Reception of the NT in the Apostolic Fathers, OUP, p.226

- ↑ "Origen on the Canon".

- ↑ See the writings of Eusebius, Apostolic Constitutions, etc.

- ↑ R.E. Heine, (2000), "In Search of Origen's Commentary on Philemon," Harvard Theological Review 93 (2000), pp. 117–133

- ↑ "Review of Bart Ehrman's book "Forged: Writing in the Name of God"... - Risen Jesus, Inc.". Risen Jesus, Inc.

- ↑ Johnson, Luke Timothy (2001), 'The First and Second Letters to Timothy: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary', Anchor Bible, ISBN 0-385-48422-4, p.91

- ↑ See I.H. Marshall, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Pastoral Epistles (International Critical Commentary; Edinburgh 1999), pp. 58 and 79. Notable exceptions to this majority position are Joachim Jeremias, Die Briefe an Timotheus und Titus (Das NT Deutsch; Göttingen, 1934, 8th edition 1963) and Ceslas Spicq, Les Epîtres Pastorales (Études bibliques; Paris, 1948, 4th edition 1969). See too Dennis MacDonald, The Legend and the Apostle (Philadelphia 1983), especially chapters 3 and 4.

- 1 2 3 4 Ehrman, Bart (2011). Forged. HarperOne. pp. 93–105. ISBN 978-006-201262-3.

- ↑ New Jerome Biblical Commentary, ed. Raymond E. Brown, S.S., Joseph A. Fitzmyer, S.J, and Roland E. Murphy, O.Carm., Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1990, pp. 811–812

- ↑ I.H. Marshall and P.H. Towner, (1999), The Pastoral Epistles (International Critical Commentary; Edinburgh: T&T Clark), p. 3, ISBN 0-567-08661-5

- ↑ See, e.g., J. J. Clabeaux, A Lost Edition of the Letters of Paul: A Reassessment of the Text of the Pauline Corpus Attested by Marcion (Catholic Biblical Quarterly Monograph Series 21; Washington, D.C.: Catholic Biblical Association, 1989

External links

- Pastoral Epistles.com:

- Early Christian Writings:

- Catholic Encyclopedia entry on the pastoral epistles

- Encyclopaedia Britannica 1911: First Epistle to Timothy

- Encyclopaedia Britannica 1911: Second Epistle to Timothy

- Pastoral Epistles: